Duke of Aquitaine

This article possibly contains original research. (May 2023) |

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2023) |

The Duke of Aquitaine (Template:Lang-oc, Template:Lang-fr, IPA: [dyk dakitɛn]) was the ruler of the medieval region of Aquitaine (not to be confused with modern-day Aquitaine) under the supremacy of Frankish, English, and later French kings.

As successor states of the Visigothic Kingdom (418–721), Aquitania (Aquitaine) and Languedoc (Toulouse) inherited both Visigothic law and Roman Law, which together allowed women more rights than their contemporaries would enjoy until the 20th century. Particularly under the Liber Judiciorum as codified 642/643 and expanded by the Code of Recceswinth in 653, women could inherit land and title and manage it independently from their husbands or male relations, dispose of their property in legal wills if they had no heirs, represent themselves and bear witness in court from the age of 14, and arrange for their own marriages after the age of 20.[1] As a consequence, male-preference primogeniture was the practiced succession law for the nobility.

Coronation

The Merovingian kings and dukes of Aquitaine had their capital at Toulouse.[citation needed] The Carolingian kings used different capitals situated farther north. In 765, Pepin the Short bestowed the captured golden banner of the Aquitainian duke, Waiffre, on the Abbey of Saint Martial in Limoges.[citation needed] Pepin I of Aquitaine was buried in Poitiers. Charles the Child was crowned at Limoges and buried at Bourges.[citation needed] When Aquitaine briefly asserted its independence after the death of Charles the Fat, it was Ranulf II of Poitou who took the royal title.[citation needed] In the late tenth century, Louis the Indolent was crowned at Brioude.[citation needed]

The Aquitainian ducal coronation procedure is preserved in a late twelfth-century ordo (formula) from Saint-Étienne in Limoges, based on an earlier Romano-German ordo. In the early thirteenth century a commentary was added to this ordo, which emphasised Limoges as the capital of Aquitaine. The ordo indicated that the duke received a silk mantle, coronet, banner, sword, spurs, and the ring of Saint Valerie.[citation needed]

Visigothic dukes

Dukes of Aquitaine under Frankish kings

Merovingian kings are in boldface.

- Chram (555–560)

- Desiderius (583–587, jointly with Bladast)

- Bladast (583–587, jointly with Desiderius)

- Gundoald (584/585)

- Austrovald (587–589)

- Sereus (589–592)

- Chlothar II (592–629)

- Charibert II (629–632)

- Chilperic (632)

- Boggis (632–660)

- Felix (660–670)

- Lupus I (670–676)

- Odo the Great (688–735), his reign commenced perhaps as late as 692, 700, or 715, unclear parentage

- Hunald I (735–745), son of Odo the Great, abdicated to a monastery

- Waifer (745–768), son of Hunald I

- Hunald II (768–769), probably son of Waifer

- Lupo II (768–781), Duke of Gascony, opposed Charlemagne's rule and Hunald's relatives.

Direct rule of Carolingian kings

Restored dukes of Aquitaine under Frankish kings

The Carolingian kings again appointed Dukes of Aquitaine, first in 852, and again since 866.[citation needed] Later, this duchy was also called Guyenne.[citation needed]

House of Poitiers (Ramnulfids)

- Ranulph I (852–866), Count of Poitiers from 835, Duke of Aquitaine from 852.

- Ranulph II (887–890), son of Ranulf I, also Count of Poitiers, called himself King of Aquitaine from 888 until his death.

House of Auvergne

- William I the Pious (893–918), also Count of Auvergne

- William II the Younger (918–926), nephew of William I, also Count of Auvergne.

- Acfred (926–927), brother of William II, also Count of Auvergne.

House of Poitiers (Ramnulfids) restored (927–932)

- Ebalus the Bastard (also called Manzer) (927–932)), illegitimate son of Ranulph II and distant cousin of Acfred, also Count of Poitiers and Auvergne.

House of Rouergue

- Raymond I Pons (932–936)

- Raymond II (936–955)

House of Capet

- Hugh the Great (955–962)

House of Poitiers (Ramnulfids) restored (962–1152)

- William III Towhead (962–963), son of Ebalus, also Count of Poitiers and Auvergne.

- William IV Iron Arm (963–995), son of William III, also Count of Poitiers.

- William V the Great (995–1030), son of William IV, also Count of Poitiers.

- William VI the Fat (1030–38), first son of William V, also Count of Poitiers.

- Odo (1038–39), second son of William V, also Count of Poitiers and Duke of Gascony.

- William VII the Eagle (1039–58), third son of William V, also Count of Poitiers.

- William VIII (1058–86), fourth son of William V, also Count of Poitiers and Duke of Gascony.

- William IX the Troubadour (or the Younger) (1086–1127), son of William VIII, also Count of Poitiers and Duke of Gascony.

- William X the Saint (1127–37), son of William IX, also Count of Poitiers and Duke of Gascony.

- Eleanor of Aquitaine (1137–1204), daughter of William X, also Countess of Poitiers and Duchess of Gascony, married the kings of France and England in succession.

- Louis the Younger (1137–52), also King of France, duke in right of his wife.

From 1152, the Duchy of Aquitaine was held by the Plantagenets, who also ruled England as independent monarchs and held other territories in France by separate inheritance (see Plantagenet Empire). The Plantagenets were often more powerful than the kings of France, and their reluctance to do homage to the kings of France for their lands in France was one of the major sources of conflict in medieval Western Europe.

House of Plantagenet

- Henry I (Henry II of England) (1152–89), also King of England, duke in right of his wife Eleanor.

- Richard I Lionheart (1189–99), also King of England, duke in right of his mother.

- John I (1199–1216), also King of England, duke in right of his mother until her death in 1204.

- Henry II (Henry III of England) (1216–72), also King of England.

- Edward I Longshanks (1272–1307), also King of England.

- Edward II (1307–25), also King of England.

- Edward III (1325–62), also King of England

Richard the Lionheart was outlived by his mother Eleanor of Aquitaine. In 1189, she acted as regent for the Duchy while he was on crusade — a position he resumed on his return to Europe.

Plantagenet rulers of Aquitaine

In 1337, King Philip VI of France reclaimed the fief of Aquitaine from Edward III, King of England.[citation needed] Edward in turn claimed the title of King of France, by right of his descent from his maternal grandfather King Philip IV of France. This triggered the Hundred Years' War, in which both the Plantagenets and the House of Valois claimed supremacy over Aquitaine.

In 1360, both sides signed the Treaty of Brétigny, in which Edward renounced the French crown but remained sovereign Lord of Aquitaine (rather than merely duke). However, when the treaty was broken in 1369, both these English claims and the war resumed.[citation needed]

In 1362, King Edward III, as Lord of Aquitaine, made his eldest son Edward, Prince of Wales, Prince of Aquitaine.[citation needed]

- Edward the Black Prince (1362–72), first son of Edward III and Queen Philippa, also Prince of Wales.

In 1390, King Richard II, son of Edward the Black Prince, appointed his uncle John of Gaunt Duke of Aquitaine. This grant expired upon the Duke's death, and the dukedom reverted to the Crown. Regardless, due to Henry IV's seizure of the crown, he still came into possession of the dukedom. [3] [better source needed]

- John of Gaunt (1390–1399), fourth son of Edward III and Queen Philippa, also Duke of Lancaster.

- Henry IV of England (1399–1400), seized the throne of England, to whose demesne the duchy had reverted upon the death of his father John of Gaunt, but ceded it to his son upon becoming King of England.

- Henry V of England (1400–1422), son of Henry IV, also King of England 1413–22.

Henry V continued to rule over Aquitaine as King of England and Lord of Aquitaine. He invaded France and emerged victorious at the siege of Harfleur and the Battle of Agincourt in 1415. He succeeded in obtaining the French crown for his family by the Treaty of Troyes in 1420. Henry V died in 1422, when his son Henry VI inherited the French throne at the age of less than a year; his reign saw the gradual loss of English control of France.[citation needed]

Valois and Bourbon dukes of Aquitaine

The Valois kings of France, claiming supremacy over Aquitaine, granted the title of duke to their heirs, the Dauphins.

- John II (1345–50), son of Philip VI of France, acceded in 1350 as King of France.

- Charles, Dauphin of France, Duke of Guyenne (1392?–1401), son of Charles VI of France, Dauphin.

- Louis (1401–15), son of Charles VI of France, Dauphin.

With the end of the Hundred Years' War, Aquitaine returned under direct rule of the king of France and remained in the possession of the king. Only occasionally was the duchy or the title of duke granted to another member of the dynasty.

- Charles, Duc de Berry (1469–72), son of Charles VII of France.

- Xavier (1753–54), second son of Louis, Dauphin of France.

The Infante Jaime, Duke of Segovia, son of Alfonso XIII of Spain, was one of the Legitimist pretenders to the French throne; as such he named his son, Gonzalo, Duke of Aquitaine (1972–2000); Gonzalo had no legitimate children.

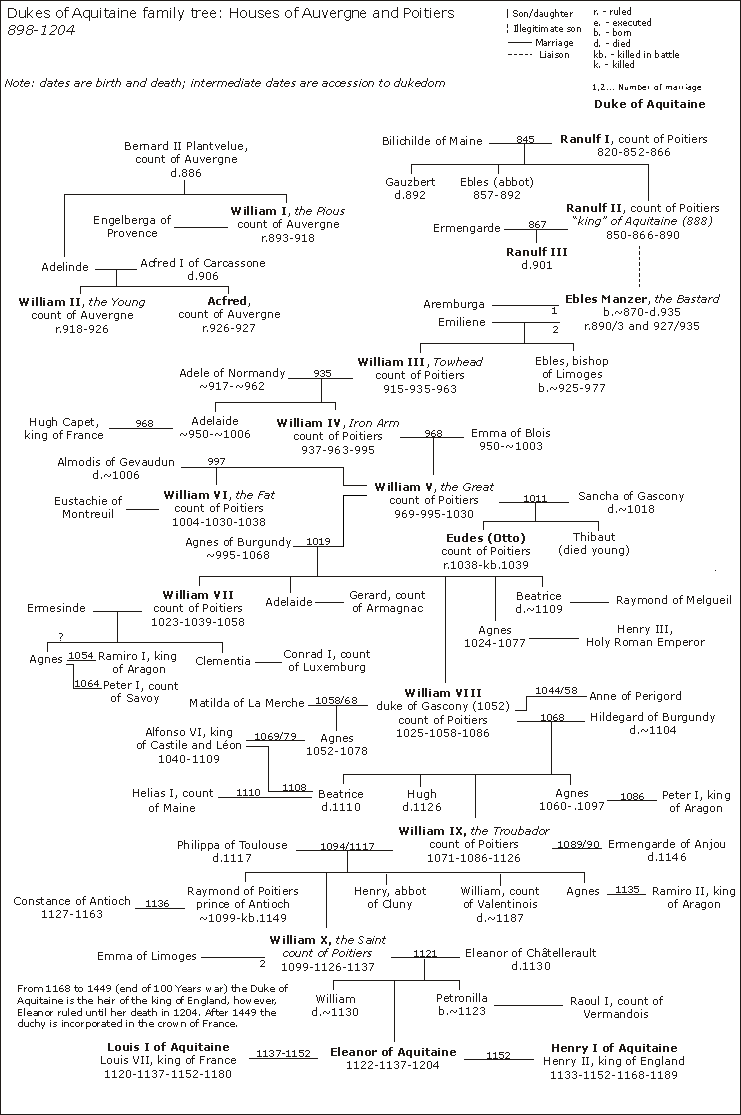

Family tree

See also

References

- ^ Klapisch-Zuber, Christiane; A History of Women: Book II Silences of the Middle Ages, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, London, England. 1992, 2000 (5th printing). Chapter 6, "Women in the Fifth to the Tenth Century" by Suzanne Fonay Wemple, pg 74. According to Wemple, Visigothic women of Spain and the Aquitaine could inherit land and title and manage it independently of their husbands, and dispose of it as they saw fit if they had no heirs, and represent themselves in court, appear as witnesses (by the age of 14), and arrange their own marriages by the age of twenty

- ^ Lemovicensis, Ruricius; Limoges), Ruricius I. (Bishop of (1999). Ruricius of Limoges and Friends: A Collection of Letters from Visigothic Gaul. Liverpool University Press. p. 15. ISBN 9780853237037.

- ^ "Would the grant of Aquitaine to John of Gaunt in 1399 have been inherited by Henry Bolingbroke had the latter not been exiled by Richard II?" at researchgate.net