Battle of Isaszeg (1849)

| Battle of Isaszeg | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Hungarian Revolution of 1848 | |||||||

Battle of Isaszeg by Mor Than | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Total: 31,315 - I corps: 10,827 - II corps: 8,896 - III corps: 11,592 99 cannons Not engaded: VII corps: 14,258 men 66 cannons |

Total: 26,000 - I corps: 15,000 - III corps: 11,000 72 cannons[1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Total: 800–1,000 killed or wounded |

Total: 369-373 killed or wounded - 81/42 dead - 196/195 wounded - 96/132 missing and captured[2] | ||||||

The Battle of Isaszeg (6 April 1849) took place in the Spring Campaign of the Hungarian War of Independence from 1848 to 1849, between the Austrian Empire and the Hungarian Revolutionary Army supplemented by Polish volunteers. The Austrian forces were led by Field Marshal Alfred I, Prince of Windisch-Grätz and the Hungarians by General Artúr Görgei. The battle was one of the turning points of the Hungarian War of Independence, being the decisive engagement of the so-called Gödöllő operation, and closing the first phase of the Spring Campaign.

This battle was the first battle between the Hungarian and the Habsburg main armies after the Battle of Kápolna, the Hungarian revolutionary army proving that they can beat the main army of one of the most powerful empires of the time. The Hungarian victory precipitated a series of setbacks to the Habsburg Imperial Armies in April–May 1849, forcing them to retreat from occupied central and western Hungary, towards the western border, opening the way towards Pest-Buda and Komárom, and convincing the Hungarian National Assembly to issue the Hungarian Declaration of Independence (from the Habsburg Dynasty). Windisch-Grätz was dismissed from the leadership of the Imperial forces in Hungary on 12 April 1849, six days after the defeat.

Background

After the Battle of Kápolna (26–27 February 1849), the commander of the Austrian imperial forces, Alfred I, Prince of Windisch-Grätz, thought that he had destroyed the Hungarian revolutionaries once and for all. In his report of 3 March sent to the imperial court in Olmütz, he wrote: "I smashed the rebel hordes, and in a few days I will be in Debrecen" (the temporary capital of Hungary).[3] Despite this he did not attack the Hungarian forces, as he lacked reliable information about the numbers facing him if he crossed the Tisza river and because of his caution, lost the opportunity to win the war.[3] While he was deciding whether to attack or not, the Hungarian commanders, who were discontented with the disappointing performance of Lieutenant General Henryk Dembiński as high commander of the Hungarian forces, blamed him for losing the Battle of Kápolna, had started a "rebellion". At a meeting in Tiszafüred, they forced the Government Commissioner Bertalan Szemere to depose the Polish general and put Artúr Görgei in command. This so infuriated Lajos Kossuth, the President of the National Defense Committee (the interim government of Hungary), that he wanted to execute Görgei for rebellion. Finally, he was persuaded by the support of the Hungarian generals for Görgei to change his mind and accept the removal of Dembiński, although his dislike of Görgei prevented him from accepting Szemere's choice of successor and he named Lieutenant General Antal Vetter high commander instead.[3] But Vetter became ill on 28 March, and after two days, Kossuth was forced to accept Görgei as temporary high commander of the Hungarian main forces.[4]

Windisch-Grätz's uncertainty was amplified by diversionary Hungarian attacks: in the south at the Battle of Szolnok on 5 March, and in the north, where on 24 March the 800-strong commando of Major Lajos Beniczky attacked an Imperial detachment under Colonel Károly Almásy at Losonc. Half of Almásy's soldiers were captured, and Almásy reported to Windisch-Grätz that he had been attacked by a 6,000-strong army. Because of this, the Austrian marshal scattered his troops in all directions to prevent a surprise attack. His main concern was a maneuver to bypass his northern flank, which he feared would raise the siege of the fortress of Komárom and cut his supply lines.[5]

On 30–31 March plans were made for a Hungarian Spring Campaign, led by General Görgei, to liberate the occupied Hungarian lands which lay to the west of the Tisza river, consisting of most of the territory of the Kingdom of Hungary. The Hungarian forces numbered some 47,500 soldiers and 198 guns, organised in four corps led by Generals György Klapka (I Corps), Lajos Aulich (II Corps), János Damjanich (III Corps) and András Gáspár (VII Corps). Windisch-Grätz had 55,000 soldiers and 214 guns and rockets, formed in three corps: I Corps (Lieutenant Field Marshal Josip Jelačić), II Corps (Lieutenant General Anton Csorich), and III Corps (General Franz Schlik), and an additional division (Lieutenant General Georg Heinrich Ramberg).[6]

The Hungarian plan, elaborated by Antal Vetter, was for VII Corps to divert the attention of Windisch-Grätz by attacking from the direction of Hatvan, while I, II, and III corps encircled the Austrian forces from the south-west, cutting them off from the capital cities (Pest and Buda). According to the plan, the VII corps had to stay at Hatvan until 5 April and then reach Bag the following day. The attack on the Austrian forces had to occur from two directions at Gödöllő on 7 April, while the I Corps advanced to Kerepes and fell on the Austrians from behind, preventing them from retreating towards Pest.[7] The key to the plan was for the Austrians not to discover the Hungarian troop movements until their encirclement was complete.[7]

Prelude

On 2 April, the preliminary fighting began when the VII Corps clashed with the Austrian III Corps at the Battle of Hatvan. Schlik had wanted to obtain information for Windisch-Grätz about the positions and numbers of the Hungarian army and had moved towards Hatvan but was defeated there by the VII Corps and forced to withdraw without accomplishing his purpose. Windisch-Grätz assumed that Schlik had come up against the main Hungarian army and remained ignorant of the true whereabouts of the Hungarian army.[8] The other three Hungarian corps moved south-west as planned and on 4 April met and defeated the Austrian I Corps at the Battle of Tápióbicske. Although Klapka's attack at Tápióbicske had revealed where the Hungarian troops really were, Görgei decided to continue with the plan.[9]

After the fighting on 4 April, Jelačić, the Ban of Croatia, claimed to Windisch-Grätz that he had actually been victorious, which misled the Field Marshal into ordering him to pursue the Hungarians. Rather than fleeing, the Hungarians were closing in on Windisch-Grätz's headquarters at Gödöllő, even as he was planning an attack on them for the following morning.[10] On 5 April he sent two companies of lancers, two companies of light horse and two rockets under the command of Lieutenant General Franz Liechtenstein on a reconnaissance mission to Hatvan.[11] After a skirmish with four companies of Hungarian hussars, in which the Hungarians retreated, Windisch-Grätz started to suspect that at Hatvan station smaller Hungarian forces, but instead of sending superior forces to defeat them, and push towards Debrecen, or to gather all his forces around Gödöllő, he did quite the opposite.[12] Fearing that the Hungarian main forces would get around him from the south and cut his lines to the capital, or from the north and liberate the fortress of Komárom from the Austrian siege, he sent the Austrian III Corps to Gödöllő and I Corps southwards to Isaszeg. Two brigades of the Austrian II Corps were also sent to Vác, and Lieutenant General Georg Heinrich Ramberg ordered to join him with his brigade; two brigades remained in Pest.[13] Windisch-Grätz had scattered his forces over 54 km (34 mi), too far apart for mutual support.[13]

Although the Hungarian front line was only 22 km (14 mi)-long, Görgei could only deploy two-thirds of his troops at any point in the battle because of his orders to his generals regarding their movements prior to the attack on 7 April, the day the battle was to begin. His orders to his corps and units in what direction to march that day, were influenced by his belief that the Austrian troops are still along the Galga line: the VII. corps had to move towards Aszód, reach the Galga, and occupy Bag; the I. corps from Süly towards Isaszeg (marching on the ridge which stretches between the two localities), sending the brigade from its left wing to Pécel; the III. corps, with maximum precautions, had to advance from Tápiószecső through Kóka and Királyerdő towards Isaszeg, sending detachments to occupy the Szent László and Szentkirály farms; and II Corps had orders to take up a position at Dány and occupy with a strong detachment Zsámbok.[14] He would be in Kóka, 15 km (9.3 mi) from Isaszeg.[15] Görgei's plan was for Gáspár to pin with the VII. corps, the Austrian left wing while the other three corps (I., II., III.) attacked their right flank at Isaszeg. This would push the Austrians northwards from Pest, enabling the liberation of the Hungarian capital on the Eastern bank of the Danube.[14] This forced a dilemma on Windisch-Grätz, to accept a battle where the Hungarians had superiority or to retreat to Pest, which was hard to defend, being open to attacks from three directions. It also had only one unfinished bridge (the Chain Bridge), to allow his troops to cross the Danube to Buda on the other side, should he need to retreat, which would have been impossible. Windisch-Grätz chose the lesser of two evils.[16]

The Field Marshal wrote on 5 April at 5:00 p.m. to Jelačić that he retreats his troops to Isaszeg, because he was informed that Hungarian troops are advancing from the south towards Pest.[14]

Opposing forces

The Hungarian army:

- I. corps:

Máriássy infantry division:

- Dipold infantry brigade: 17 infantry companies, 8 cannons = 2475 soldiers;

- Bobich infantry brigade: 18 infantry companies, 6 cannons = 3129 soldiers;

Kazinczy infantry division:

- Bátori-Sulcz infantry brigade: 18 infantry companies, 8 cannons = 2086 soldiers;

- Zákó infantry brigade: 6 infantry companies, 8 cannons = 1052 soldiers;

- Dessewffy cavalry brigade: 16 cavalry companies = 2085 soldiers

10,827 soldiers (59 infantry companies, 16 cavalry companies), 30 cannons.

- II. corps:

Hertelendy combined division:

- Patay infantry brigade: 20 infantry companies, 14 cannons = 3028 soldiers;

- Mándy cavalry brigade: 9 cavalry companies, 8 cannons = 3129 soldiers;

Szekulits infantry division:

- Mihály infantry brigade: 15 infantry companies, 6 cannons = 2202 soldiers;

- Buttler infantry brigade: 12 infantry companies, 8 cannons = 2515 soldiers;

8896 soldiers (47 infantry companies, 9 cavalry companies), 36 cannons[17]

- III. corps:

Knezich infantry division:

- Kiss infantry brigade: 16 infantry companies, 8 cannons = 2658 soldiers;

- Kökényessy infantry brigade: 15 infantry companies, 3 cannons = 2511 soldiers;

Wysocki infantry division:

- Leiningen infantry brigade: 12 infantry companies, 8 cannons = 1772 soldiers;

- Czillich infantry brigade: 16 infantry companies, 8 cannons = 2373 soldiers;[a]

- Kászonyi cavalry brigade: 16 cavalry companies, 6 cannons = 2278 soldiers;[b]

11,592 soldiers (59 infantry companies, 16 cavalry companies), 33 cannons.[18]

- VII. corps:

1. (Gáspár) division:

- Horváth brigade: 39. infantry battalion, 6 companies of the 9. (Nicholas) hussar regiment, 2. six pounder cavalry battery;

- Waldberg brigade: 1. battalion of the 60. (Wasa) infantry regiment, 4. six pounder infantry battery;

- Petheő brigade: Nógrád battalion, 2 companies of the Újház jägers, 2 sapper companies, the Pozsony six pounder battery;[19]

2. (Kmety) division:

- Gergely brigade: 10. infantry battalion, 23. infantry battalion, 1 sapper company, 3. six pounder infantry battery;

- Újváry brigade: 45. infantry battalion, 2 companies of jägers, 4 companies of the 9. (Wilhelm) hussar regiment, 4. six pounder cavalry battery;

- Üchritz brigade: 33. infantry battalion, 2. infantry battalion from Besztercebánya, 2 companies of the 12. (Nádor) hussar regiment, 5. six pounder cavalry battery;

3. (Poeltenberg) division:

- Kossuth brigade: 1. infantry battalion, 1. infantry battalion from Besztercebánya, 2 companies of the 4. (Alexander) hussar regiment, 5. six pounder infantry battery;

- Zámbelly brigade: 14. infantry battalion, 1. infantry battalion from Pest, 4 companies of the 4. (Alexander) hussar regiment, 1. six pounder cavalry battery;

4. (Simon) division:

- Weissl brigade: 4 companies of grenadiers, 2. battalion of the 48. (Ernest) infantry regiment, 1 company of German Legion, 1 howitzer battery;

- Liptay brigade: 4 companies of the Tyrolian jägers, 1 sapper company, 1 howitzer cavalry battery, 2 Congreve rocket launching racks;[20]

14,258 soldiers (101 infantry companies, 24 cavalry companies), 66 cannons.[21]

The Austrian army:

- I. corps:

Hartlieb infantry division:

- Gramont infantry brigade: 24 infantry companies, 6 cannons;

- Rastić infantry brigade: 21 infantry companies, 6 cannons;

Dietrich infantry division:

- Budissavliević infantry brigade: 18 infantry companies, 6 cannons;

- Mihić infantry brigade: 15 infantry companies, 6 cannons;

Ottinger cavalry division:

- Fejérváry cavalry brigade: 12 cavalry companies, 6 cannons;

- Sternberg cavalry brigade: 14 cavalry companies, 6 cannons;

Other units:

- Infantry reserve: 2 infantry companies;

- Artillery reserve: 36 cannons;

≈15,000 soldiers[22] (80 infantry companies, 26 cavalry companies), 72 cannons[23]

- III. corps:

Lobkowitz division:

- Parrot brigade: 3. battalion of the 3. (Archduke Karl) infantry regiment, 1. battalion of the 12. (Wilhelm) infantry regiment, 1. battalion of the 24. (Parma) Landwehr regiment, 3. battalion of the 30. (Nugent) infantry regiment, 2 companies of the 2. jäger battalion, 1 company of the 1. (Imperial) chevau-léger regiment, 36. six pounder infantry battery;

- Künigl brigade: 3. battalion of the 12. (Wilhelm) infantry regiment, 3. battalion of the 40. (Koudelka) infantry regiment, 2. battalion of the 28. (Latour) infantry regiment, 2 companies of the 1. (Imperial) chevau-léger regiment, 34. six pounder infantry battery;

Liechtenstein division:

- Fiedler brigade: 3. battalion of the 58. (Archduke Stefan) infantry regiment,[24] 2. battalion of the 9. (Hartmann) infantry regiment, 3. battalion of the 10. (Mazzuchelli) infantry regiment, 4 companies of the miscellaneous Ecker battalion;

- Montenuovo cavalry brigade: 2 companies of the 1. (Imperial) chevau-léger regiment, 2 companies of the 7. (Kress) chevau-léger regiment, 6 companies of the 10. (King of Prussia) cuirassier regiment, 2 companies of the 2. (Sunstenau) cuirassier regiment, 2. cavalry battery;

The artillery reserve of the corps:

- Schlik six-pounder infantry battery, 11. Congreve rockets battery, 12. Congreve rockets half battery.[24]

≈11,000 soldiers[22] (62 infantry companies, 16 cavalry companies), 46 cannons[23]

Isaszeg and its surroundings in 1849

The battlefield of Isaszeg lies in the hilly area formed by the wooded extensions of the southern edge of the Cserhát mountains, crossed by the Rákos creek flowing through Gödöllő and Isaszeg, which turns abruptly at Pécel towards west.

Being shallow, this creek usually did not represent an important barrier for anybody, but the heavy snowfalls and rains from the beginning of April 1849 changed this situation completely, making its banks marshy and its riverbed sludgy, which made its crossing very difficult, except through the bridges laying in Isaszeg, Gödöllő and at a couple of hundred meters north from the latter locality. East to Gödöllő, until the monastery of Máriabesnyő, and south from it, lies a depression, continued, towards the Galga valley, by the deep valleys of the Aranyos and Egres creeks. The stream of the Rákos is accompanied from both sides by gently sloping flat-topped hills, which become high and abrupt only on its right bank, right in front of Isaszeg, rising considerably above the village, the wide valley, with accidented terrain, and the woody highland, which lie west from it. The region east of the monastery of Máriabesnyő and Isaszeg was covered by woods, called in 1849 Királyerdő (the King's Wood), which encircled Isaszeg semicircularly. Királyerdő was a 14,000 paces long, well-managed, easy-to-cross forest, with many clearings, having its narrowest portion, along the Isaszeg-Dány road, around its middle 1200 paces, and at Alsó malom (Lower Mill) around 4000 paces, being on its southern end even wider. The wide vineyard on the northern end of Királyerdő, as well as the deer park southeast from Gödöllő, were also important natural shelters for the combatants on the left bank of the Rákos. Despite being more fragmented than those from the left bank, the heights on the right bank of the Rákos were unforested, thus they were harder to hide the troops' movements.[14]

The territory of the future battlefield was favorable for a battle. The defender, with the Rákos creek in front of the frontline, could find advantageous places to deploy its batteries on the heights from the right bank. The right wing of the defensive position, with the Várhegy hill, despite the village of Pécel, had advantageous, defendable slopes, while the left wing at Gödöllő, was more exposed to the danger of encirclement. Another disadvantage of the defensive position was the unfortunate position of Isaszeg, in front of the front line, which made it necessary to station troops at its eastern edge, which made the village an outpost, a target for the concentrated artillery fire of the enemy. The region east of the Rákos creek, despite the woods, did not impede the attackers' movements and deployment, providing them also cover from the enemies' eyes and artillery, being also favorable for installing artillery positions. On the other hand, because of the forest and the muddy, slippery sandy banks of the Rákos, for both the defenders and attackers, the use of the cavalry was problematic (but despite of this, as will be seen below, the cavalry was not entirely neglected in this battle).[14]

Battle

On 6 April at 6:00 a.m., following Windisch-Grätz's order, the Austrian troops concentrated at Aszód and Bag retreated towards Gödöllő, while a part of the II. corps of Csorich marched towards Vác and the III. corps of Schlik, at 10:30 a.m., deployed at Gödöllő, covered by the vanguard represented by the Schütte brigade, at the monastery of Máriabesnyő.[14] Jelačić arrived at Isaszeg at 11:00 a.m., with his troops tired of the long marching, and set up camp on the heights behind the village.[16] He reported to Windisch-Grätz that, during his march towards Isaszeg, his I. corps was followed from a distance by a Hungarian detachment of one infantry battalion, 3 cavalry companies, and 1 battery, and saw also 4 enemy columns following him, but he could not estimate their number, because of the great distance. Because of this, Jelačić urged Windisch-Grätz to unite the I. and the III. corps.[14] Jelačić deployed his corps positioning the Rastić brigade at the edge of the Királyerdő forest along the road from Kóka to Gödöllő and Isaszeg, while the Gramont brigade occupied the southeastern edge of the same forest.[14]

Around 1:00 p.m. the III. corps of Schlik was preparing for lunch when they heard the cannon fire coming from the south, and Windisch-Grätz saw an enemy column approaching from the direction of Aszód, so he ordered the Lobkowitz division to occupy their position east from Gödöllő. The Austrian soldiers departed with the meat, which they received for lunch, stuck on their bayonets.[14]

On 6 April Görgei gave orders for his troops to move and occupy the forming up points ready for the Hungarian attack due the next day. When the troops moved to the places where they were supposed to wait, they encountered Austrian soldiers and an encounter battle began; both commanders were surprised, causing haste and confusion.[25] Gáspár moved with his 14,258 troops and 66 guns to Aszód, Tura and Bag on the bank of the river Galga at 12:30 p.m., where he did not found any enemy. He sent, around 12:30 p.m. Colonel György Kmety with a division to occupy Hévízgyörk, where they stumbled on Schlik's cavalry, composed by the Auersperg cuirassiers; after the Austrians retreated, the Hungarians halted.[14] Gáspár did not move his troops forward even after hearing gunfire, claiming that he was obeying the orders he had received from Görgei the previous day to remain in that position until the following day, which meant that VII. Corps, the largest of the four Hungarian corps (I: 10,817 men, II: 8,896, III: 11,592), was absent throughout the battle.[26] Hearing about the attack against the Auersperg cuirassiers, Windisch-Grätz sent the Lobkowitz division to halt them, wanting to send also the Liechtenstein division after them, but when he was informed that Kmety practically stopped, he understood that the Hungarians will not attack from the north, so he held the Liechtenstein division back, then sent it towards the Királyerdő forest, to support Jelačić's I. corps.[14] Kmety indeed, after deploying his artillery, and ordering his cavalry to make some demonstration attacks, did not move further, knowing that Gáspár will remain with the Kossuth and Poeltenberg divisions at Bag, and will not support him in the case of an attack.[14]

At the same time, Klapka's and Damjanich's two corps arrived in the vicinity of Királyerdő (King's Forest) east of Isaszeg.[27] Being ahead of Klapka's corps, first Damjanich's vanguard found enemy troops in its way, around 1:00 p.m. they started the fight. Damjanich's troops attacked the rear brigade of the Austrian I Corps (the Rastić brigade), chasing it out of the forest to Isaszeg. To prevent the Hungarians to follow them, the Croatians set fire to the forest in several places.[27] Arriving in Sáp shortly after 1:00 p.m., Klapka prepared to cross the Királyerdő forest, and head towards Isaszeg, sending the Zákó brigade as the vanguard, preceded by a thick line of skirmishers, on the road, followed by the Bobich brigade, and in the rear with the artillery and cavalry of the corps. Left from them, the Schulcz brigade, followed by the Dipold brigade, headed towards the southeastern edge of the forest, in the direction of Pécel.[14] When the Zákó brigade approached the Királyerdő woods to 1500 paces, they heard the sounds of the shots from the north, signaling the start of the fight of Damjanich's troops with the enemy.[14]

Then the 34. battalion and the six-pounder battery of the Zákó brigade attacked Major-General Franz Adam Grammont von Linthal's brigade composed of Croatian border guards and kaiserjägers, chasing them out of the forest towards Isaszeg,[27] and arriving to the southwestern edge of the woods.[14] Meanwhile, the 28. battalion of the Bobich brigade organized in skirmisher lines also chased out the Austrians from Királyerdő, and continuing their advance also on the open field, they broke into Isaszeg, followed by the 34. battalion,[27] putting in danger also the Rastić brigade, which (as seen before, was forced to retreat from the forest by Damjanich's troops) was trying to cross on the right bank of the Rákos creek.[14] Noticing the danger, Jelačić sent two brigades from the Dietrich (according to Bánlaky Schultzig)[14] division in support of his troops from Isaszeg, so the overwhelming superiority (3 infantry and 1 cavalry brigades) of the Austrian I Corps prevailed, causing to the two Hungarian battalions important losses, and forcing them to retreat in disorder in the Királyerdő forest. Jelačić sent the Austrian cuirassiers and kaiserjägers to pursue them. The retreating 28. battalion run into the lines of the deploying Bobich brigade, causing them too to retreat.[27] This happened around 2:30 p.m.[14] Finally, the 44th and 47th battalions, which were behind them, shot a salvo at the cuirassiers, which were attacked suddenly from the side also by the Bátori-Sulcz brigade, causing them to retreat. Then 44. and 47. battalions attacked and chased also the Austrian kaiserjägers out from Királyerdő woods.[27] But when the regrouped Bobich and Bátori-Sulcz brigades tried again to gain terrain outside the forest, the fire of the Croatian seressaners, positioned on the heights near Isaszeg prevented them to do this.[27]

At this moment Klapka, a very capable Hungarian general and one of the heroes of the Hungarian war of independence, inexplicably lost his head and left his commanders to their own devices.[28] Trying to take the initiative into their own hands, the Bobich brigade started an attack, but they were repulsed by the Austrian fire, which caused them to retreat, as well as the majority of Klapka1s troops, leaving important portions of the forest unprotected.[28] Damjanich remained the only commander who tried, with his corps, to resolve the mounting problems for the Hungarian army. He sent one of his brigades to the northern edge of the forest. He then positioned his cavalry and his 4 batteries under Colonel Nagysándor between his corps and Klapka's, in the middle angle of the forest on a bare hill, engaging in an intense artillery duel with the Austrians.[14] Damjanich intended to attack to relieve the pressure on Klapka but the latter, feeling that his situation was hopeless, started to withdraw his troops before help arrived.[29] Damjanich remained, trying to solve this problem by himself, and when he saw the Austrian troops pursue Klapka's retreating brigades, he sent his best units to help Klapka: the Kiss brigade with the 9th ("Red Hatted") battalion and the 3rd battalion of the Wasa regiment (not to be confused with the "White Feathered" 3. battalion).[14] Jelačić, seeing this, and also noticing that at the southwestern edge of the forest the Dipold and the Bátori-Sulcz brigades threaten his right flank with encirclement (unfortunately for him, he did not know that these brigades do not intend to attack because the Zákó and Bobich brigades on their right were in total disarray), renounced to continue the attack against the forest, and retreated his corps on the heights from the right bank of the Rákos creek, positioning the 5. kaiserjäger battalion, on his left flank, at the lower mill (alsó malom) from Gödöllő, the Dietrich division on his right flank on the eastern slope of the Várhegy height, and with the bulk of his corps the area behind Isaszeg. He also positioned important infantry units at the southeastern edge of the village.[14]

Around 3:00 p.m. two of the four Hungarian corps (I. and III.) were fighting in an uncoordinated manner, with half of them retreating, while the other two (II. and VII.) were far from the battlefield, unaware of the situation; Görgei was still in Kóka, ignorant of what was going on, preparing for a battle that he thought would start the following day.[28] According to some claims he did not inform his headquarters from Dány that he was in Kóka, so his officers did not know where to find him. Because of this Görgei did not know about what was happening on the battlefield.[14]

In the meantime, Damjanich, who was the only commander who was fighting, held with his infantry the northern portion of the forest, the troops of Nagysándor were still holding the opening from the middle section of Királyerdő, although some of its cavalry units from the left flank retreated under the influence of the retreating Zákó brigade, and the section southeast from Isaszeg was still held by the Kiss brigade.[14] The only units of the I. corps which still held their positions were the Bátori-Sulcz and Dipold brigades from the eastern edge of the left wing.[14] To make the situation even worse, Klapka gave the general order to retreat, but luckily Major Bódog Bátori-Sulcz, a man hard of hearing, understood quite the opposite, so he remained in his position.[28] Momentarily only the batteries of Nagysándor and the Austrian artillery were fighting with each other.[14] Despite this desperate situation, around 3:00 p.pm, Damjanich decided to attack the Austrian troops by himself. Organizing his infantry in two lines, and positioning cavalry squadrons on the wings, he attacked the heights from the bank of the Rákos,[14] but, thinking that Gáspár's VII. corps will keep Schlik's III. corps at bay, he did not scout the forested region north from his troops, thus he did not secure his right flank enough. He did not know that Gáspár did not attack, enabling Schlik to send the Liechtenstein division, to help Jelačić, shortly after the battle started.[28] Without Damjanich's knowing, Liechtenstein sent 8 cavalry companies and a Congreve rocket battery along the Rákos's bank under the leadership of Colonel Kisslinger, to support the I. corps directly, heading with the 4 companies, accompanied by the infantry and artillery of the Liechtenstein division, under the leadership of Colonel Montenuovo, towards the northern edge of the Királyerdő forest. They were led by the commander Windisch-Grätz, who left Gödöllő because he wanted to take a look over the battlefield from this position.[14] The four cavalry companies arrived in the vineyards right when the attack of Damjanich's troops started. A battery accompanied by the Hartmann battalion and two companies of the Mazzuchelli battalion took position on the vineyards, while left from them, the other batteries and the rest of the Fiedler brigade continued their way towards the forest.[14] The Hungarians had hardly begun to advance when from their right side, from the vineyards between the lower mill and the Királyerdő his troops were hit by a tremendous cannon and rifle fire.[14] Now the III Corps was caught between two fronts, forcing Damjanich to retreat to Királyerdő.[30] Understanding his mistake of not scouting the region north from him, Damjanich sent the Polish Legion and the 3. "White Feathered" battalion to chase out the Fiedler brigade from the northern section of the woods, but the fierce fight which ensued, momentarily none of the two sides was able to prevail.[14] First the Austrian Hartmann, then the Mazzuchelli and Breisach battalions attacked, but after they advanced 300 paces, they were pushed back by the Hungarian volley, then later, between 4:00 and 5:00 p.m. the reorganized brigade, reinforced also by the Archduke Stephan battalion, tried another attack, but the Hungarians, now reinforced by the Leiningen brigade, repulsed them, killing Major Piatolli, the leader of the Hartmann battalion.[14] Later, towards the evening, reinforced also by a kaiserjäger battalion, sent from the around the lower mill, the Austrians tried also the fourth attack, but the Hungarians, meanwhile reinforced with new units, repulsed them again.[14]

On the Austrian right wing around 4:00 p.m., Windisch-Grätz ordered Jelačić to start a general attack against the Hungarians from all directions.[31] But seeing that, despite repulsing Damjanich's attack, on the left flank his troops cannot break through, he ordered Jelačić to attack on the center, sending the 26 cavalry companies of the I. corps led by Lieutenant General Ferenc Ottinger, reinforced by the 8 cavalry companies and 1 battery of the Liechtenstein division led by Colonel Kisslinger to support them.[14] At that point the situation of the Hungarian left wing was serious. The only brigades of Klapka's corps, which were still fighting (the Bátori-Sulcz and the Dipold brigades), isolated on the left flank, being caught in a crossfire from the direction of the Várhegy mountain and Isaszeg, they too retreated into the forest.[14] This was a critical moment of the battle, because there were 26,000 Austrian troops on the battlefield against 14,000 Hungarians, with only half of the Hungarian artillery.[32] Excepting Kmety's division from the VII. corps and the III. corps, all the other Hungarian units being away, or retreating from the battlefield, but if we count only the troops directly involved in the battle, then we must count only Damjanich's III. corps, while from the other side Jelačić's I. corps and the Liechetnstein division of Schlik's III. corps (because as shown before, the Kmety and the Lobkowitz divisions were just stationed in front of each other), which results in 11,600 Hungarians actively fighting against around 20,000 Austrians.[27]

Around 3:00 p.m., Aulich's II Corps stood still in Dány and Zsámbok, guarding the headquarters of the Hungarian army. Even though earlier he had received a message from Damjanich to hurry to the battlefield, Aulich, like Gáspár, insisted on obeying Görgei's orders of the day before to remain in position. Only after the Chief of General Staff Lieutenant-Colonel József Bayer, hearing the sounds of the cannonade, ordered him to advance, did he finally depart with his troops towards Isaszeg.[28]

While around 3:00 p.m., Görgei, unaware of the battle, was still in Kóka, one of his grooms rode ahead and hearing the sounds of the battle, went back, and informed Görgei about this.[14] According to other sources he was informed by a hussar that the battle is about to be lost. Hearing this, Görgei mounted and hurried towards the battlefield,[28] sending also an envoy to order Aulich to attack (as seen before, at that moment the latter was already marching towards the battlefield).[14] Görgei arrived at the eastern edge of the Királyerdő forest at 4:00 p.m., just as Aulich's corps arrived and was about to join the battle. He was also told that VII Corps had occupied its position on the Galga river line. Görgei made the mistake of not sending an order to Gáspár to advance, thinking that he was already doing so, whereas Gáspár was just standing in position waiting for new orders. Görgei wrote in his memoirs that he was misinformed by the hussar who brought Gáspár's report, saying that his commander was advancing towards Gödöllő. Görgei now thought that he would easily encircle and destroy the Austrian main body if Gáspár's corps attacked the Austrians from the north-east, as Damjanich's troops would hold the line in the forest and Klapka together with Aulich would do an encircling attack from the south and chase the Austrians to the north.[28] The plan failed because Görgei failed to send the message and because Gáspár chose to remain in his position despite hearing the cannonade.[33][34][c]

The Hungarian difficulties did not end with the arrival of Görgei and Aulich. Klapka was still retreating and the places on the edge of the forest that he left empty could be occupied by the Austrian troops, cutting the Hungarian army in two.[35] Görgei distributed the battalions of II Corps among the endangered zones with four battalions (the Mihályi brigade reinforced by the 48. battalion)[14] to the right wing to help Damjanich, two in the middle to fill the gap created by Klapka's retreat, and the 61st Battalion to help Klapka on the left wing.[35] Then Görgei rode to the left flank and consulted with Klapka, who still wanted to continue his retreat, saying that his troops had run out of ammunition and were very tired, so "today it is impossible to obtain victory, but tomorrow it will be possible again". Görgei replied: "[...] the quickness of your infantry's retreat shows that they are not that tired, so they can try some bayonet attacks, and for these, they have enough cartridges even if they have indeed really used them all. We have to win today, or we can go back to the swamps of the Tisza! Only two solutions exist, we have no third. Damjanich is still holding out at his post, and Aulich is advancing - we must win!"[35] These words convinced Klapka to order his troops to move forward again and occupy Isaszeg.[35]

Görgei then hurried to the right flank and told Damjanich that he had convinced Klapka to stop the retreat and attack. Damjanich showed no confidence in Klapka but obeyed his commander and continued to resist Liechtenstein's attacks. The eventual arrival of Aulich's four battalions created confusion because the III Corps troops thought that they were Austrians and briefly opened fire, being stopped only by Damjanich's and Görgei's intervention. The long fight on the right flank disordered Damjanich's battalions, so he could not use his ten battalions to attack the five Austrian infantry battalions which faced them. This task was made impossible also by the numerical superiority of the Austrian cavalry, which had 34 squadrons against 17 on the Hungarian side, and by their artillery, as they had twice as many guns as Damjanich; on the right flank, excepting the successful resistance (as it was shown earlier) of the 3. battalion and the Polish legion against the renewed attacks of the Fiedler brigade, nothing, in particular, happened until around 11:00 p.m.[35] The 25th, 48th, 54th, 56th battalions of II Corps, together with III Corps, pushed the Austrians towards Gödöllő.[36]

In the middle of the battlefield, the battle between the 34 Austrian and the 17 Hungarian cavalry companies was in full progress.[35] First Ottinger wanted to attack from the direction of Isaszeg, but the village was burning, and the Hungarian artillery unleashed a very efficient bombardment of that area.[14] So Ottinger tried to find a safer crossing point on the Rákos creek north from Isaszeg, but when they tried to cross the marshy banks of the creek, Nagy Sándor's artillery, reinforced also by the batteries of the just arrived II. corps appeared on the heights in front of them and bombarded them so efficiently, that they were unable to accomplish their attack.[14] The grave situation of the Austrian cavalry was tried to be used by the Hungarian hussars, who attacked the Austrian cavalry, but they were bombarded by the batteries of Fiedler from the vineyards and the battery of Kisslinger from the direction of Isaszeg. At this moment the hussars were suddenly attacked from the side and from behind by the 4 companies of Colonel Montenuovo, forcing them to retreat to the forest.[14] The misfortune followed the hussars even in the forest, where a battery of the Aulich corps, thinking that they are Austrians, fired on them with grapeshot.[14] A similar accident happened also at the northern edge of the forest, where the Mihályi brigade shot the units of the Wysocki division from the back.[14]

After this first cavalry battle followed another, Nagysándor sending the remaining hussar companies of his division, reinforced also by a hussar company of the II. corps led Lieutenant Colonel Mándy, against the companies of Ottinger and Kisslinger. This attack ended in a stalemate, when the horses, being forced to fight on the sandy and muddy terrain from the banks of the Rákos, became exhausted, so both sides retreated, looking at each other from a safe distance until the end of the battle.[14]

On the left flank, Klapka ordered the Zákó and the Bobich brigades to advance, and occupy again the southwestern section of the forest, where together with the Kiss brigade (III. corps), were fiercely attacked by Jelačić's troops, holding their lines with great difficulty.[14] Under the continuous attacks of Jelačić's I. corps, the Bobich brigade (28., 46., and 47. battalions), deployed on both sides of the Isaszeg-Sülysáp road, left from them Kiss brigade (the 9th "Red feathered" battalion, and the 3. Wasa brigade), on the end of the left flank being represented by the Bátori-Sulcz brigade (the 17. battalion and the 3. battalion of the Don Miguel infantry regiment), with the Dipold brigade behind them, while the II. corps was still deploying in the gap between the I. and the III. corps.[14]

Around 7:00 p.m. Klapka prepared for the decisive attack, when Jelačić's troops, after renewed unsuccessful attacks, retreated to their initial positions. The Hungarian attack was much more successful, Klapka's and Aulich's troops managing to emerge from the Királyerdő forest with the help of the Hungarian guns, captured the burning village of Isaszeg with a bayonet charge, and repulsed the Austrian troops from the right bank of the Rákos creek, continuing their successful advance also on the heights from the right bank of the Rákos. Here the Austrian troops did not show any resistance, because Jelačić ordered them to retreat toward Gödöllő.[14] Klapka's fatigued troops, together with the bulk of the II. corps did not follow the retreating enemy, setting up camp around 8 p.m. on the heights.[14] Only some minor hussar units from the II. corps led by Captain Jelics followed the Austrians on a short distance.[14] Chief of staff Lieutenant-Colonel József Bayer, hearing at Dány about the success, ordered I. Corps to pursue the Austrians and advance to Kerepes to cut their retreat towards Pest, but Klapka refused, pointing to the fatigue of his troops. This made Bayer rightfully criticize him because of that.[14]

Of the Hungarian corps commanders, it was Klapka, despite his initial setbacks, who decided the fate of the battle for the Hungarians.[37] While on the left wing the battle was won around 8 p.m., on the right wing Damjanich and Windisch-Grätz had no clue about this.[14] The retreating Jelačić did not inform Windisch-Grätz about his retreat, who at 7:00 p.m. was thinking that he had won the victory.[14] Around 9:00 p.m. Jelačić wrote to his commander to install his outposts on the actual positions, and to pursue the Hungarians with his cavalry, enabling in this way the I. and III. corps to join.[14] This contradictory report left Windisch-Grätz in the darkness, the Field Marshal thinking, at this point, that the outcome of the battle was at least a draw.[14] So, hindered more and more by the ensuing darkness, the fights on the northern portion, continued here until 11 p.m.[14] Only around 11:00 p.m., when Jelačić arrived in Gödöllő, and told to Windisch-Grätz, that he could not remain for the night in his disadvantageous position, so he had to retreat to Gödöllő, he finally learned that the battle was lost.[14]

On the Hungarian side too, the uncertainty about the outcome of the battle lasted for a long time. Long after the battle was decided by the attack of I. Corps, Görgei was still uncertain about the result, because on the right wing and in the center the fighting continued until late in the evening. Only when he rode to the left flank did he learn from Aulich that Austrian I. Corps had begun retreating towards Gödöllő and realized that the Hungarians had won the battle.[38]

Around midnight Windisch-Grätz gathered his troops, retreating from there in a freezing temperature in a night march.[14]

Additional battle maps

Maps of the important moments of the battle

-

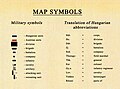

Map symbols for the Isaszeg battle maps, and the English meanings of the Hungarian abbreviations

-

The position of the armies before the battle.

-

The situation at 12:30 p.m. Red - the Austrian troops, Blue - the Hungarian troops.

-

The situation from 06.04.1849. The situation at 14,00 o'clock

-

The situation at 3:00 p.m. Red - the Austrian troops, Blue - the Hungarian troops.

-

The situation at 4:30 p.m. Red - the Austrian troops, Blue - the Hungarian troops.

-

The situation at 5:30 p.m. Red - the Austrian troops, Blue - the Hungarian troops.

-

The situation at 6:00 p.m. Red - the Austrian troops, Blue - the Hungarian troops.

-

The situation at 7:00 p.m. Red - the Austrian troops, Blue - the Hungarian troops.

-

The situation at 8:00 p.m. Red - the Austrian troops, Blue - the Hungarian troops.

Aftermath

After the battle of Isaszeg, the Hungarians sat camp around Gödöllő, being so confident of the effect of their victory on the Austrians, that they did not even deploy outposts to warn them in the case of a surprise attack by Windisch-Grätz's army.[14] But the latter did not think of any other attack but ordered his troops to retreat to Pest.[14] As a result of this, although they won the victory, and forced the Austrian imperial main army to retreat, Görgei could not accomplish his plan of encircling and annihilating them, or at least force them to retreat towards Vienna on the left shore of the Danube, leaving the Hungarian capital unprotected.[39]

About the losses of the two armies, there are no exact data. It is estimated that the Hungarians lost around 800–1000 in dead, wounded, or missing soldiers.[14] According to József Bánlaky (Breit), only the Liechtenstein division has exact statements about their losses: 3 officers and 61 soldiers dead, 7 officers and 78 soldiers wounded, and 15 men missing; in total 10 officers and 154 soldiers.[14] According to Róbert Hermann Jelačić's I. corps lost 17 dead, 111 wounded and 81 missing or captured soldiers, while the Liechtenstein division lost 64/25 dead, 85/84 wounded, and 15/51 captured or missing soldiers; in total 373/369 men.[2] According to Bánlaky, some sources show 600, while other sources 1500 Austrian losses.[14]

On the day after the battle of Isaszeg, Lajos Kossuth, the President of the National Defense Committee arrived in Gödöllő and moved into the Grassalkovich Palace, which had been Windisch-Grätz's headquarters until the previous day.[40] Although Kossuth was thinking about the declaration of independence for a while, the Hungarian victories which started on 2 April with the battle of Hatvan, culminating with Isaszeg, strengthened his determination that this was the right moment for this defining political act.[41] At Gödöllő, on 7 or 8 April, Kossuth told Görgei about the plan of the declaration of independence, who did not openly object but tried to make Kossuth change his mind by saying that many of the officers may dislike this move, because they have legitimist feelings, wanting to keep the emperor as king of Hungary, and the freedom must be won on the battlefield, and not in the national assembly. But Kossuth did not give much importance to Görgei's objections, and on 14 April 1849 in Debrecen the Hungarian National Assembly, presided by Kossuth, declared the Dethronement of the Habsburg dynasty, and issued the Hungarian Declaration of Independence.[42]

The battle of Isaszeg, following the Battle of Kápolna, was the second confrontation between the Hungarian revolutionary and the Austrian armies. Although it was not a crushing defeat for either of the combatants, it influenced the morale both of the victors and the defeated. While the Hungarian generals, except Ándrás Gáspár, showed the ability to take decisions when they were on their own, the Imperial generals, other than Franz Schlik, failed from this point of view. Windisch-Grätz misunderstood the situation completely before the battle, scattering his troops so that Anton Csorich's II Corps and Georg Heinrich Ramberg's division could not participate in the battle. Although Görgei had made mistakes too, such as wrongly believing that Gáspár had joined the battle, he succeeded in committing the majority of his troops and winning the battle.[43] The battle of Isaszeg was in contrast to the Battle of Kápolna where, in a similar situation, the Hungarian commander Henryk Dembiński had failed to coordinate his troops on the battlefield, allowing Windisch-Grätz to win.[44]

The most important result of the battle was that the military initiative was taken for two months by the Hungarian army, while the Habsburg army was defeated in a series of battles (Battle of Vác, Battle of Nagysalló, Battle of Komárom, Siege of Buda), and forced to retreat towards the west. Also, the Battle of Isaszeg played a decisive role in Windisch-Grätz being relieved of command of the Habsburg armies by the emperor on 12 April, who named Feldzeugmeister Ludwig von Welden in his place, although until his arrival his duties were fulfilled by Josip Jelačić.[45] The changes in the leadership did not produce a change in the military situation for the Austrian side, their situation continued to worsen day by day because of the new defeats they suffered, which caused their retreat from almost all the territory they occupied in Hungary between December and March.[46]

During the battle, all Hungarian corps commanders made greater or lesser mistakes. Even Damjanich, who stood the ground alone against the Austrian army during the most critical moments of the battle, thus being the man who saved the army from a crushing defeat, made the error of exposing his right flank to Liechtenstein's attack, thinking that Gáspár's corps protects his back. Görgei too let his troops alone, without telling them where to be found in a critical moment, and his belief that the battle will occur only the next day does not excuse him. Also, his omission to send an order to Gáspár to attack with all his forces Schlik's corps prevented the Hungarian army to achieve an even greater victory.[14]

Also in Gödöllő, the plan for the second phase of the Spring Campaign was formulated. This plan was based on making the Imperial high command believe that the Hungarian army wanted to liberate the capitals of Hungary: Pest and Buda, when in fact their main forces would move north, liberating the Hungarian fortress of Komárom, besieged since January by the Imperial forces. While II Corps under Lajos Aulich remained in front of Pest, with the duty of misleading the Imperial forces, making such brilliant military maneuvers that the Austrian commanders thought that the Hungarian main forces were still in front of the capital planning to make a frontal attack against it, the I, III and VII Corps accomplished the campaign plan perfectly, and on 26 April relieved the fortress of Komárom. This forced the main Austrian forces based in the capital, except for 4,890 soldiers who were left to hold the fortress of Buda, to retreat to the Austrian border, thus liberating almost all of Hungary from Austrian occupation.[47]

Legacy

The famous Hungarian Romantic novelist Mór Jókai, himself participant in the events of the Hungarian revolution of 1848–49, made the Hungarian Revolution and War of Independence the subject of his popular novel A kőszívű ember fiai (literally: The Sons of the Man with a Stone Heart, translated into English under the title: The Baron's sons), written in 1869. In chapters XIX and XX, the Battle of Isaszeg is vividly presented as one of the main plot events of the novel, in which several of his main characters appear as fighters in the ranks of both the Hungarian and the Austrian army.[48] This novel was also adapted as a movie in 1965, having the same title (A kőszívű ember fiai) as the novel, and including the Battle of Isaszeg as one of its most important scenes.[49] Nowadays the battle is re-enacted every year on its anniversary, 6 April, in and around Isaszeg.[50]

Explanatory notes

- ^ In the battle of Isaszeg this brigade is led by Józef Wysocki.[14]

- ^ According to other sources the cavalry of the III. corps was led by Colonel József Nagysándor.[14]

- ^ László Pusztaszeri explains that Gáspár's inactivity was due in part to his pro-Imperial feelings and that after the Declaration of the Dethronement of the Habsburg Dynasty by the Hungarian Parliament on 14 April 1849, he asked for permission to go on leave, and ultimately never returned to service with the Hungarian army.[33][34]

Notes

- ^ Hermann 2013, pp. 20–23.

- ^ a b Hermann 2013, pp. 25.

- ^ a b c Hermann 2001, pp. 244.

- ^ Hermann 2001, pp. 263.

- ^ Hermann 2001, pp. 271.

- ^ Hermann 2001, pp. 268–269.

- ^ a b Hermann 2001, pp. 270

- ^ Hermann 2013, pp. 14–16.

- ^ Hermann 2004, pp. 218.

- ^ Hermann 2013, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Hermann 2001, pp. 274–275.

- ^ Bánlaky József: Lovas összeütközés Hatvan előtt. 1849. április 5-én. A magyar nemzet hadtörténete XXI Arcanum Adatbázis Kft. 2001

- ^ a b Hermann 2001, pp. 275.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh bi bj bk bl Bánlaky József: Az isaszegi csata (1849. április 6-án). A magyar nemzet hadtörténete XXI Arcanum Adatbázis Kft. 2001

- ^ Hermann 2004, pp. 224.

- ^ a b Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 252.

- ^ Hermann 2013, pp. 22.

- ^ Hermann 2013, pp. 23.

- ^ Csikány 1996, pp. 51.

- ^ Csikány 1996, pp. 52.

- ^ Hermann 2004, pp. 229.

- ^ a b Hermann 2013, pp. 20.

- ^ a b Hermann 2004, pp. 230.

- ^ a b Csikány 1996, pp. 50.

- ^ Hermann 2004, pp. 224, 228.

- ^ Hermann 2004, pp. 224, 229.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Hermann 2004, pp. 225.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Hermann 2004, pp. 226.

- ^ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 255–256.

- ^ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 256.

- ^ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 257.

- ^ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 256–257.

- ^ a b Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 258.

- ^ a b Bóna 1987, pp. 157.

- ^ a b c d e f Hermann 2004, pp. 227.

- ^ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 259.

- ^ Hermann 2004, pp. 228.

- ^ Hermann 2004, pp. 227–228.

- ^ Csikány Tamás: Hadművészet az 1848-49-es magyar szabadságharcban Zrínyi, Budapest 2008

- ^ Merva 2007, pp. 282.

- ^ Arany, Krisztina. "A Függetlenségi Nyilatkozat". Retrieved 3 August 2022.

- ^ Bona Gábor: 5. A Függetlenségi Nyilatkozat és a hadsereg tisztikara. Az 1848/49-es szabadságharc tisztikara. Tábornokok és törzstisztek az 1848/49. évi szabadságharcban NKA 2015

- ^ Hermann 2013, pp. 25–26.

- ^ Hermann 2013, pp. 26.

- ^ Hermann 2001, pp. 285.

- ^ Hermann 2001, pp. 314.

- ^ Hermann 2001, pp. 282–295.

- ^ Jókai 1900, pp. 242–253.

- ^ Men and Banners, Internet Movie Database

- ^ "Hadak Útja Lovas Sportegyesület 2015. Avagy ez történt eddig, ebben az évben…". Archived from the original on 9 October 2015. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

Sources

- Asztalos, István (2007). Isaszeg (in Hungarian). Budapest: NKÖEOK Szerkesztőség. Száz magyar falu könyvesháza. ISBN 978-963-9287-37-2.

- Bánlaky, József (2001). A magyar nemzet hadtörténelme (The Military History of the Hungarian Nation XXI) (in Hungarian). Budapest: Arcanum Adatbázis.

- Bóna, Gábor (1987). Tábornokok és törzstisztek a szabadságharcban 1848–49 [Generals and Staff Officers in the War of Independence 1848–1849] (in Hungarian). Budapest: Zrínyi Katonai Kiadó. ISBN 963-326-343-3.

- Csikány, Tamás (1996). "A hatvani ütközet". In Horváth, László (ed.). Hatvany Lajos Múzeum Füzetek 13. A tavaszi hadjárat. Az 1996. március 14-i tudományos konferencia anyaga (in Hungarian). Hatvan Hatvany Lajos Múzeum. ISBN 963-04-7279-1.

- Csikány, Tamás (2008). Hadművészet az 1848-49-es magyar szabadságharcban("The Military Art of the Freedom War of 1848-1849") (in Hungarian). Budapest: Zrínyi Miklós Nemzetvédelmi Egyetem Hadtudományi Kar. p. 200.

- Hermann, Róbert, ed. (1996). Az 1848–1849 évi forradalom és szabadságharc története [The History of the Hungarian Revolution and War of Independence of 1848–1849] (in Hungarian). Budapest: Videopont. ISBN 963-8218-20-7.

- Hermann, Róbert (2001). Az 1848–1849-es szabadságharc hadtörténete [Military History of the Hungarian War of Independence of 1848–1849] (in Hungarian). Budapest: Korona Kiadó. ISBN 963-9376-21-3.

- Hermann, Róbert (2004). Az 1848–1849-es szabadságharc nagy csatái [Great Battles of the Hungarian War of Independence of 1848–1849] (in Hungarian). Budapest: Zrínyi. ISBN 963-327-367-6.

- Hermann, Róbert (2013). A magyar függetlenségi háború [Great Battles 16: The Hungarian Freedom War]. Nagy csaták. 16. (in Hungarian). Budapes t: Duna Könyvklub. ISBN 978-615-5129-00-1.

- Hermann, Róbert (2018). "A tápióbicskei ütközet. 1849 április 4-én" [The Battle of Tápiobicske. On 4 April 1849]. In Pelyach, István (ed.). Damjanich János : "a mindig győztes" tábornok [János Damjanich : "The Always Victorious General"]. New York: Line Design. pp. 171–194. ISBN 978-963-480-006-4.

- Jókai, Maurus (1900). The Baron's Sons: A Romance of the Hungarian Revolution of 1848. London: Walter Scott Publishing. OCLC 977705602.

- Merva, Mária G. (2007). Gödöllő története I. A kezdetektől 1867-ig [The History of Gödöllő: From the Beginnings until 1867] (in Hungarian). Vol. I. Gödöllő: Gödöllői Városi Múzeum. ISBN 978-963-86659-6-6.

- Nobili, Johann. Hungary 1848: The Winter Campaign. Edited and translated Christopher Pringle. Warwick, UK: Helion & Company Ltd., 2021.

- Pusztaszeri, László (1984). Görgey Artúr a szabadságharcban [Artúr Görgey in the War of Independence] (in Hungarian). Budapest: Magvető Könyvkiadó. ISBN 963-14-0194-4.

External links

- (in Hungarian) Video animation about the Battle of Isaszeg

- (in Hungarian) Modern day reenactment of the battle, on 06.04.1014