Saint Francis's satyr

| Saint Francis's satyr | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Lepidoptera |

| Family: | Nymphalidae |

| Genus: | Neonympha |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | N. m. francisci

|

| Trinomial name | |

| Neonympha mitchellii francisci Parshall & Kral, 1989[5]

| |

| |

| NC range by county in red[6] | |

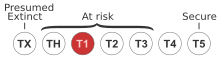

The Saint Francis's satyr (Neonympha mitchellii francisci) is an endangered butterfly subspecies found only in the US state of North Carolina. First discovered in 1983, it was first described by David K. Parshall and Thomas W. Kral in 1989 and listed as federally endangered by the US Fish and Wildlife Service in 1994. It is a subspecies of N. mitchellii and is restricted to a single metapopulation on Fort Liberty military base in Hoke and Cumberland counties.[7] The other subspecies, Mitchell's satyr (Neonympha mitchellii mitchellii), is also federally endangered.[8]

Physical characteristics

The Saint Francis's satyr is a small butterfly with an average wingspan of 34–44 mm. It is dark brown, with distinguishing eyespots along the lower surfaces of both the upper and lower wings. The eyespots on its wings are primarily dark brown or maroon, rimmed with yellow and with flecks of white that reflect silver in the middle. They are usually round or slightly oval and found on the forewing and hindwing. There are two bright orange bands running along the lower wing edges and two darker orange bands across the middle of each wing. Females appear slightly larger and lighter brown than males, which is an example of sexual dimorphism.[7]

Life history and reproduction

Adults live an average of three to four days. The subspecies is bivoltine, having two mating events per year. The first flight period occurs from late May to early June, and the second from late July to mid-August. Females deposit eggs individually or in small clusters that emerge as larvae in seven to ten days.[4] Caterpillars that emerge in early summer period form a chrysalis after two months, while those that emerge in late summer period hibernate over winter and pupate the following spring. Pupation may take up to two weeks. There is little historical information on the life history of the butterfly. Because of this, current research is being done at Michigan State University[9] and North Carolina State University[7] to better understand the butterfly's role in its ecosystem.

Diet

One known larval host plant of the Saint Francis's satyr is Mitchell's sedge (Carex mitchelliana), although it is likely that other sedges in the genus Carex also act as host plants.[10]

The diet of the Saint Francis's satyr as an adult consists primarily of nectar and tree sap. It also has been known to consume dung, pollen, and rotten fruit. In many cases, it is attracted to sodium, resulting in attraction to human sweat.[7]

Historic and present range

The Saint Francis's satyr was discovered in south-central North Carolina in 1980. Due to poaching and the lack of monitoring programs, many experts believed the species went extinct. Despite this, the species was rediscovered in 1992. Currently, the butterfly's range is completely isolated to the training fields of Fort Liberty, a military base in Cumberland and Hoke counties in North Carolina.[7] Though Fort Liberty is the largest military installation in the world, the butterflies only occupy a 10 square kilometer (3.38 square mile) area on the base.[7] Historically, several smaller subpopulations fell within the total range; currently, just a single metapopulation exists. The butterfly continues to be highly restricted in its distribution and has never been found outside of Fort Liberty.[11]

Habitat

The Saint Francis's satyr's habitat is composed of wide, open grasslands; wetlands; and sedge-dominant ecosystems that experience regular natural disturbance.[11] This disturbance is a result of beaver dam construction, natural fires, rainfall, or flooding. As a generally sedentary butterfly with delicate needs, it is imperative that these natural disturbances are maintained to create the habitat the butterfly needs to thrive. In addition to natural disturbances, the military operations at Fort Liberty create regular disturbances that help form wet meadows on the base. This habitat creation allows the Saint Francis' satyr population to be maintained at Fort Liberty.[11]

Present and historic population size

Currently, not much is known about the butterfly's historic population size. From 2002 to 2005, the population size of the Saint Francis's satyr was estimated to be between 500 and 1400 butterflies.[11] Usually small, their fragmented sites range from 0.2 to 2.0 hectares in size. Current numbers are estimated to be no more than 1000 individuals with no single population producing greater than 100 butterflies a year.[7] The decrease in population size throughout the years could be a result of fire suppression and beaver extermination.[11]

Endangered Species Act listing history

The butterfly was first listed under the Endangered Species Act in 1994 under an emergency rule, after threats of poaching and loss of habitat increased.[3] Since its listing, there have been notable efforts towards preventing the collection of these butterflies. However, poaching is still a threat due to the butterfly's rarity. To combat this, any known listings of colony location sites are kept from the public record. Between 1998 and 2016, more than $3 million were spent on additional conservation efforts for the Saint Francis' satyr. The main focus for conservation of these butterflies is continuing to preserve and grow the existing subpopulations, as well as enforcing the strict regulations on poaching and collecting. The five-year review for this species suggests the preservation of existing suitable habitats and for continued searching for the establishment of new populations.[12] The IUCN has yet to evaluate the Saint Francis' satyr.

Major threats

The Endangered Species Act (1973) outlines five criteria for committees to evaluate a species' status, seen below. At the time of its emergency listing in 1994, the Saint Francis' satyr faced threats in multiple of these categories.

Destruction, modification, or curtailment of habitat or range: The Saint Francis's satyr has experienced extensive habitat destruction and modification due to environmental change in the past 100 years. These changes resulted in the loss of the creation of wet meadow habitat due to beaver hunting and control measures, as well as human fire suppression. Experts believe the butterfly used to occupy a larger range but it has been reduced to two counties in North Carolina.[4]

Overutilization for commercial, recreational, scientific, or educational purposes: Overcollection for recreational and aesthetic purposes was a serious threat at the time of the butterfly's listing, largely due to the butterfly's rarity.[4]

Disease or predation: There was no conclusive evidence of disease or predation as a threat to the Saint Francis's satyr.[4]

Inadequacy of existing regulatory mechanisms: There were no regulatory mechanisms on the local or federal level in place at the times of its listing.[4]

Other natural or man-made factors affecting continued existence: Natural factors affecting the Saint Francis' satyr's continued existence include limited dispersal ability and the resulting difficulty in establishing new colonies. The natural metapopulation structure of butterfly populations also presents challenges because it increases the likelihood of population destruction in extreme events such as natural disasters. The butterfly also has a higher likelihood of extinction due to disease because of reduced genetic variation in the population.[4]

Anthropogenic factors affecting the Saint Francis's satyr's continued existence include close proximity to roads increasing the likelihood of butterfly death via toxic chemical spills, pest control programs that help to mitigate the effects of mosquitoes and gypsy moths that harm butterfly populations, and human fire exclusion limiting the formation of habitat land for the Saint Francis's satyr.[4] However, its location on the Fort Liberty military base increases its survival because the frequent ecological disturbances created by troop movements allow meadow creation.

Current conservation efforts

Experts recommend downlisting the Saint Francis's satyr once two criteria are met: the metapopulation has stabilized or increased in number for at least 10 to 15 years and once there is a long-term plan to manage the species' survival.[13] To do so, there are regulations and a recovery plan in place.

Regulations

The ESA prohibits the sale, import, export, and removal of the Saint Francis's satyr to limit collection pressures.[13] There are also laws preventing federal agencies from taking part in activities that will harm the species in areas where they are vulnerable, including road construction, pesticide application, and beaver control.[4] However at the time of its listing, there were no laws in place in North Carolina protecting these butterflies.[12] Currently, laws have been passed to protect butterfly populations and their habitat, including regulations for federal agencies, prohibitions of certain practices, and recovery plans.[13]

Recovery plan

The following recovery plan strives to improve conditions for Saint Francis's satyr survival so that it can be downlisted to threatened before being delisted completely. Experts view a stable metapopulation as 200 adult individuals per brood.[12]

Protect and manage existing populations and their habitat:[13] This stage of the plan focuses on three key aspects.

- Monitoring existing populations:[13] A monitoring system has been in place since 2002 and has estimated population sizes at sites found outside artillery impact areas.[12]

- Protecting existing populations:[13] Researchers keep colony locations confidential and restrict military traffic around colony sites.[12]

- Managing for long-term species survival:[13] Researchers develop continual disturbance plans to create meadow habitat. Plans will outline goals, strategies, timelines, and funding sources. However, long-term management plans are incomplete because there needs to be a better understanding of disturbance factors.[12]

Continued research:[13] There is still much to learn about the life history of this butterfly, so research collaborations have been formed with North Carolina State University[12] and other organizations such as the Department of Defense.[4] These collaborations have yielded valuable information regarding population trends, species-habitat interactions, and dependence on disturbance.[12]

Search for additional populations:[13] Researchers have found three new subpopulations, but they are all restricted to Fort Liberty. In addition, the locations of these sites are highly restricted, so it has been difficult to monitor the population's health.[12]

Establish more wild populations in historic range:[13] This involves rearing butterflies in captivity for release and protecting habitat suitable for new colony sites. As of the five-year recovery plan in 2013, no new populations had been established. However, restoration efforts in four sites created meadows in 2011 so that they could potentially house future butterfly populations.[12] Once new populations are established, experts hope to increase connectivity between populations by implementing movement corridors.[4]

Implement information and education programs:[13] Since the public plays a large role in conservation, education programs are necessary for the success of this plan. Education plans focus on eliminating illegal collection and creating collaborations with landowners to restore commercial land to habitat suitable for these butterflies. Most outreach has been in the form of publication.[12]

Since the Saint Francis's satyr has not yet been downlisted, the five-year review recommends continuance with the goals outlined in the recovery plan in addition to preservation of existing suitable habitat and restoration of new suitable land for colonization.[12]

Taxonomy

Following its discovery, the Saint Francis's satyr was listed as a subspecies of the Mitchell's satyr (Neonympha mitchellii). The nominate subspecies, N. m. mitchellii, is distributed sparsely in the mid- and eastern US, including in Michigan, Alabama, Mississippi, and Virginia, and formerly New Jersey. Although the Alabama, Mississippi, and Virginia populations are morphometrically similar to Saint Francis's satyr, current molecular evidence supports that they are distinct from Saint Francis's satyr and that Saint Francis' satyr should remain as a separate subspecies from all other populations in the genus Neonympha with potential elevation to full species status pending further analysis.[14][15]

References

- ^ NatureServe (7 April 2023). "Neonympha mitchellii francisci". NatureServe Network Biodiversity Location Data accessed through NatureServe Explorer. Arlington, Virginia: NatureServe. Retrieved 26 April 2023.

- ^ "Saint Francis' satyr butterfly (Neonympha mitchellii francisci)". Environmental Conservation Online System. U.S. Fish & Wildlife Department. Retrieved 26 April 2023.

- ^ a b 59 FR 18324

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Saint Francis' Satyr Determined To Be Endangered" (PDF). Federal Register. 60 (17): 5264–5267. January 26, 1995. Retrieved 26 April 2023.

- ^ "ITIS Standard Report Page: Neonympha mitchellii francisci". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved December 19, 2013.

- ^ "Saint Francis' Satyr (Neonympha mitchellii francisci)". U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Archived from the original on December 20, 2013. Retrieved December 19, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Saint Francis' satyr". Southeast Region of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Archived from the original on 9 November 2021.

- ^ "Mitchell's Satyr (Neonympha mitchellii mitchellii)". Midwest Region Endangered Species. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 29 May 2019. Archived from the original on 5 April 2021.

- ^ KBS News, Publications (18 June 2019). "New book chronicles researcher's quest for the world's rarest butterflies". W.K. Kellogg Biological Station. Michigan State University. Retrieved 26 April 2023.

- ^ "The Saint Francis' Satyr – the Rarest Butterfly in North Carolina". Three Rivers LandTrust. August 29, 2016. Retrieved April 15, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Kuefler, Daniel; Haddad, Nick M.; Hall, Stephen; Hudgens, Brian; Bartel, Becky & Hoffman, Erich (April 2008). "Distribution, Population Structure and Habitat Use of the Endangered Saint Francis Satyr Butterfly, Neonympha mitchellii francisci". The American Midland Naturalist. 159 (2): 298–320. doi:10.1674/0003-0031(2008)159[298:DPSAHU]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0003-0031. S2CID 84946882.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation" (PDF). U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. November 15, 2013. Retrieved April 15, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Murdock, Nora (April 23, 1996). "Recovery Plan: St. Francis' Satyr" (PDF). U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. Retrieved April 16, 2020.

- ^ Kuefler, Daniel; Haddad, Nick M.; Hall, Stephen; Hudgens, Brian; Bartel, Becky & Hoffman, Erich (2008). "Distribution, Population Structure and Habitat Use of the Endangered Saint Francis Satyr Butterfly, Neonympha mitchellii francisci" (PDF). The American Midland Naturalist. 159 (2): 298–320. doi:10.1674/0003-0031(2008)159[298:DPSAHU]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0003-0031. S2CID 84946882.

- ^ Hamm, C. A.; Rademacher, V.; Landis, D. A. & Williams, B. L. (2013). "Conservation Genetics and the Implication for Recovery of the Endangered Mitchell's Satyr Butterfly, Neonympha mitchellii mitchellii" (PDF). Journal of Heredity. 105 (1): 19–27. doi:10.1093/jhered/est073. ISSN 0022-1503. PMID 24158752.

- Bartel, Rebecca A.; Haddad, Nick M. & Wright, Justin P. (2010). "Ecosystem engineers maintain a rare species of butterfly and increase plant diversity" (PDF). Oikos. 119 (5): 883–890. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0706.2009.18080.x. Retrieved October 29, 2010.

- Lessig, H.; Wilson, J.; Hudgens, B. & Haddad, N. (2010). "Research for the conservation and restoration of an endangered butterfly, the St. Francis' satyr". Report to the Endangered Species Branch, Ft. Bragg NC.

- Parshall, David K. & Kral, Thomas W. (1989). "A new subspecies of Neonympha mitchellii (French) (Satyridae) from North Carolina" (PDF). Journal of the Lepidopterists' Society. 43 (2): 114–119. Retrieved October 29, 2010.

- U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1996. Saint Francis' Satyr Recovery Plan. Atlanta, GA. 27 pp.

- Williams, Ted (1996). "The great butterfly bust". Audubon. 28 (2): 30–37.

External links

- Haddad, Nick. "St. Francis satyr". Ecology and Conservation Biology in the Haddad Lab. North Carolina State University. Retrieved October 29, 2010.

- "Saint Francis Satyr in North Carolina". U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Retrieved November 29, 2010.

- "Saint Francis' Satyr Butterfly". The Butterfly Conservation Initiative. 2006. Archived from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved October 29, 2010.

- Black, S. H.; Vaughan, D. M. (2005). "Satyrs: St. Francis' satyr (Neonympha mitchellii francisci)". The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation. Retrieved October 29, 2010.

- "Mitchell's Satyr (Neonympha mitchellii mitchellii)". Michigan Department of Natural Resources and Environment. 2001–2010. Retrieved October 29, 2010.

- "Of Bombs and Butterflies". Radiolab. WNYC. October 15, 2021.