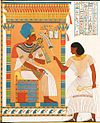

Royal sealer (Ancient Egypt)

| |||

| Royal sealer in hieroglyphs | |||

|---|---|---|---|

The royal sealer or royal seal-bearer[1] (Template:Lang-egy) was an Ancient Egyptian official position and title. The name literally means "sealer of the king of Lower Egypt," but it seems unlikely that the position was ever geographically limited.[2] In the Early Dynastic period and Old Kingdom, it was one of the most important positions in Egypt. The bearer seems to have headed the treasury and had significant symbolic power as an official representative of the Pharaoh. As a "ranking title," it indicated the bearer's pre-eminence in court. In the late Middle Kingdom, it was revived as a ranking title borne by many of the highest officials in the court. This apparently coincided with an increased prominence of seals in the Egyptian administration, as part of a centralisation of the bureaucracy. The title spread more widely in the Second Intermediate period, diluting its power.

History

Early dynastic and Old Kingdom

Royal sealers first appear in the Early Dynastic Period, when they were probably the highest treasury officials. The first holders of the office are attested in the reign of Den: Setka, known from a seal that he used to oversee the sub-department of oil or wine pressing,[3][4] and Hemaka, known from a tomb at Saqqara, whose scale and sumptuous grave goods demonstrate the office's preeminent position at this stage.[4] The appearance of this office coincides with a step change in the sophistication and complexity of Egypt's administrative organisation.[5] The possession of the king's seal also gave the officeholders significant symbolic authority,[4] and it seems to have been used in part as a "ranking title", to indicate the officeholder's prominence in court.[6]

As the distinction between the Pharaoh's personal estate and the state treasury (pr-ḥḏ) developed in the late Early Dynastic Period and early Old Kingdom, royal sealers may have become administrators of the personal estate.[7] In the Third Dynasty under Pharaoh Djoser, it was the main title held by Imhotep, the architect of the Step Pyramid, showing that it continued to be one of the preeminent offices of Egypt.[4] In the Fourth Dynasty, the office was often held by the vizier.[8] In the Fifth Dynasty, royal sealers were among the officials in charge of the whole treasury, perhaps acting as checks on the power of other officials, by virtue of their role as personal representatives of the king in financial matters.[9]

Middle Kingdom

In the second half of the Twelfth Dynasty, in or after the reign of Senusret II (1897–1878 BC), the title of royal sealer was revived as the main ranking title for the highest officials, beneath the titles of iry-pat and ḥaty-a, which were thereafter reserved for the few most prominent officials in court,[10][11] and above the title of smḥr-wꜥty.[12] These titles were additive, so a royal sealer promoted to the higher ranks continued to bear the title of royal-sealer as well.[12] The introduction of the title seems to be linked with a marked increase in the use of seals by royal officials and the appearance of the practice of counter-sealing (where a document is sealed by several different officials). At the same time, the position of overseer of sealed things (ỉmy-r ḫtmt) was created as head of the economic administration with equal status to the vizier. These changes are signs of increased centralisation of the Egyptian administration.[11]

The title of royal sealer was not limited to official working in the royal treasury. It is often linked with specific powerful roles, like the overseer of the enclosure (ỉmy-r ḫnrt, responsible for the organisation of corvee labour throughout the country), the commander of the ruler's crew (in charge of the royal guard),[13] and the nomarchs.[14]

Second Intermediate period

During the Second Intermediate Period, when central authority broke down in Egypt, titles referring to seals proliferate and the title of "royal sealer" comes to be used for a much wider array of officials, including many officials involved in religious and local administration. The title continues to appear In the Seventeenth Dynasty the title of king's son (s3 nsw) becomes the chief ranking title held by the most prominent officials, supplanting but not totally replacing the title of "royal sealer". This may reflect a shift in governing ideology, in which personal connections to the Pharaoh became more important as marks of status.[15]

When the position of high priest (i.e. a priest in charge of administration of a temple) began to emerge in the Thirteenth dynasty, that role began to be indicated by combining the title ḥm-nṯr ("priest", held by many priests in a temple), with the title of royal sealer.[16] This becomes more common during the Second Intermediate Period and coincides with an increasing role of high priests in the Pharaoh's central administration. In the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Dynasties, the title spreads to other important temple officials.[17] In the New Kingdom, a specific title for the high priest was created, ḥm-nṯr tpy ("first priest").[16]

References

- ^ "Royal chancellor" and "treasurer" are also used as English translations, but are used for a number of other titles, including the common honorific ỉmy-ỉs: Papazian 2013, p. 52.

- ^ Wilkinson 1999, pp. 111–12.

- ^ Papazian 2013, p. 76.

- ^ a b c d Wilkinson 1999, pp. 111–112.

- ^ Barta 2013, p. 160.

- ^ Barta 2013, p. 156-157.

- ^ Papazian 2013, p. 57.

- ^ Barta 2013, p. 164.

- ^ Papazian 2013, p. 75.

- ^ Grajetzki 2013, p. 224.

- ^ a b Shirley 2013, p. 540.

- ^ a b Willems 2013, p. 372.

- ^ Grajetzki 2013, p. 234 & 256.

- ^ Willems 2013, pp. 372 & 391.

- ^ Shirley 2013, p. 548 & 552-53.

- ^ a b Grajetzki 2013, p. 258.

- ^ Shirley 2013, p. 563-64.

Bibliography

- Barta, Miroslav (2013). "Kings, Viziers, and Courtiers: Executive Power in the Third Millennium B.C.". In Moreno Garcia, Juan Carlos (ed.). Ancient Egyptian administration. Leiden, The Netherlands. pp. 153–177. ISBN 9789004250086.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Grajetzki, Wolfram (2013). "Setting a State Anew: The Central Administration from the End of the Old Kingdom to the End of the Middle Kingdom". In Moreno Garcia, Juan Carlos (ed.). Ancient Egyptian administration. Leiden, The Netherlands. pp. 215–258. ISBN 9789004250086.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Papazian, Hratch (2013). "The Central Administration of the Resources in the Old Kingdom: Departments, Treasuries, Granaries and Work Centers". In Moreno Garcia, Juan Carlos (ed.). Ancient Egyptian administration. Leiden, The Netherlands. pp. 41–84. ISBN 9789004250086.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Shirley, JJ (2013). "Crisis and Restructuring of the State: From the Second Intermediate Period to the Advent of the Ramesses". In Moreno Garcia, Juan Carlos (ed.). Ancient Egyptian administration. Leiden, The Netherlands. pp. 521–606. ISBN 9789004250086.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Willems, Harco (2013). "Nomarchs and Local Potentates: The Provincial Administration in the Middle Kingdom". In Moreno Garcia, Juan Carlos (ed.). Ancient Egyptian administration. Leiden, The Netherlands. pp. 341–392. ISBN 9789004250086.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Wilkinson, Toby (1999). Early dynastic Egypt. London: Routledge. ISBN 9780415186339.