Brucella abortus

| Brucella abortus | |

|---|---|

| |

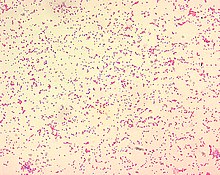

| Brucella spp. are gram-negative in their staining morphology. Brucella spp. are poorly staining, small gram-negative coccobacilli (0.5-0.7 x 0.6-1.5 µm), and are seen mostly as single cells and appearing like "fine sand". | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | B. abortus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Brucella abortus (Schmidt, 1901) Meyer and Shaw, 1920

| |

Brucella abortus is a Gram-negative bacterium in the family Brucellaceae and is one of the causative agents of brucellosis. The rod-shaped pathogen is classified under the domain Bacteria.[1] The prokaryotic B. abortus is non-spore-forming, non-motile and aerobic.[2]

Transmission

Brucella abortus enters phagocytes that invade human and animal innate defenses which in turn, cause chronic disease in the host. The liver and spleen are the mainly affected areas of the body.[3] Farm workers and veterinarians are the highest risk individuals for acquiring the disease due to their close proximity to the animals. Swine, goats, sheep, and cattle are a few of the reservoirs for the disease.[4] B. abortus causes abortion and infertility in adult cattle and is a zoonosis which is present worldwide.[5] Humans are commonly infected after drinking unpasteurized milk from affected animals or, less commonly, when coming into contact with infected tissues and liquids (afterbirth, etc.).[6]

The incubation period for the disease can range from 2 weeks to 1 year. Once symptoms begin to show, the host will be sick anywhere from 5 days to 5 months, depending on the severity of illness. A few of the symptoms of brucellosis include: fever, chills, headache, backache, and weight loss. As with any disease, there can be serious complications; endocarditis and liver abscess are a couple of complications for brucellosis.[7] Although rare, B. abortus (and other Brucella spp.) can be transmitted between humans, usually via sexual transmission.

B. abortus also affects bison.[8]

Species

Brucella has twelve different kinds of species, one being Brucella abortus.[9] Some of the other species are known as B. melitensis, B. canis, B. suis, B. ovis, B. neotomae, B. ceti, and B. pinnipediae. Each species displays an affinity for specific animals or groups of animals.[10] Cattle and other livestock are the major host species for the bacteria B. abortus.[9] It is usually found to colonize in the liver and spleen.

There are many different ways B. abortus can spread from the different animals and even to humans. Human infections can lead to Bang's disease.[9] When cattle have stillbirths and are carrying this disease, other animals nearby can get infected if they ingest it or otherwise come into contact with fluids containing the bacteria. It could also be passed by their semen and urine.[11] Ticks are another source of transmission for B. abortus.[11]

Survival

Temperature plays a huge role in the survival of B. abortus.[12] The bacteria can survive for a longer period of time if they are at a cooler temperature. This is why it can transmit through liquids like milk and tap water.[12] B. abortus can last a lot longer in animals if they are not watched closely and if the cattle are not treated for it. In humans, it can be caught after noticing signs and the correct tests to determine the type of bacteria.[11]

References

- ^ "National Institutes of Health (NIH)". National Institutes of Health (NIH). Archived from the original on 2019-05-29. Retrieved 2017-10-25.

- ^ "CDC Works 24/7". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2017-10-24. Retrieved 2017-10-25.

- ^ "CDC Works 24/7". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2017-10-24. Retrieved 2017-10-25.

- ^ "CDC Works 24/7". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2017-10-24. Retrieved 2017-10-25.

- ^ Dorneles, EM; Sriranganathan, N; Lage, AP (8 July 2015). "Recent advances in Brucella abortus vaccines". Veterinary Research. 46 (1): 76. doi:10.1186/s13567-015-0199-7. PMC 4495609. PMID 26155935.

- ^ Scott, PR; Penny, CD; Macrae, A, eds. (2011). "Brucellosis". Cattle Medicine. London: Manson Pub. p. 34. ISBN 978-1840766110.

- ^ "microbewiki". microbewiki.kenyon.edu. Retrieved 2017-10-25.

- ^ Lott, Dale F. (2002). American bison: a natural history. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 109. ISBN 978-0520233386.

- ^ a b c Kaden, R.; Ferrari, S.; Jinnerot, T.; Lindberg, M.; Wahab, T.; Lavander, M. (2018). "Brucella Abortus: Determination of survival times and evaluation of methods for detection in several matrices". BMC Infectious Diseases. 18 (1): 259. doi:10.1186/s12879-018-3134-5. PMC 5989407. PMID 29871600.

- ^ "Humans and Brucella Species". 13 June 2019.

- ^ a b c "Brucellosis: Brucella Abortus" (PDF).

- ^ a b Kaden, R.; Ferrari, S.; Jinnerot, T.; Lindberg, M.; Wahab, T.; Lavander, M. (2018). "Infectious Diseases: Brucella Abortus". BMC Infectious Diseases. 18 (1): 259. doi:10.1186/s12879-018-3134-5. PMC 5989407. PMID 29871600.