A Survivor from Warsaw

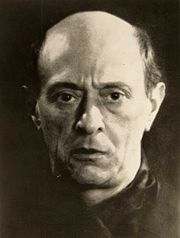

A Survivor from Warsaw, Op. 46, is a cantata[1] by the Los Angeles–based Austrian composer Arnold Schoenberg, written in tribute to Holocaust victims. The main narration is unsung; "never should there be a pitch" to its solo vocal line, wrote the composer.[2]

Scored for narrator, men's chorus and orchestra, it resulted from a suggested collaboration between Jewish Russian émigrée dancer Corinne Chochem and Schoenberg, but the dancer's initiative gave way to a project independently developed by the composer after he received a commission from the Koussevitzky Music Foundation for an orchestral work. Concept, text, and musical sketches date from July 7 to August 10, 1947 – the text, by Schoenberg, being in English until the concluding Hebrew plea, except for interjections in German. Composition followed immediately, from August 11 to 23,[3] four years before the composer died. The work was premiered by the Albuquerque Civic Symphony Orchestra under the direction of Kurt Frederick on November 4, 1948.

Czech writer Milan Kundera dedicated an essay in his book Encounter (2010) to A Survivor from Warsaw. It annoys him that educated people don't know that the cantata "is the greatest memorial ever dedicated to the Holocaust... [but] people are fighting to ensure that the killers are not forgotten. But they forget Schönberg."[4]

Story

The work narrates the story of a survivor of the Warsaw Ghetto in the Second World War, from his time in a concentration camp. The Nazi authorities one day hold a roll-call of a group of Jews. The group tries to assemble but there is confusion and the guards beat the old and ailing detainees who cannot line up quickly enough. Those left on the ground are presumed dead. The guards demand another count to determine how many will be deported to death camps. The guards repeatedly demand the group to count faster until the detainees break into sung prayer, the Shema Yisrael, ending with Deuteronomy 6:7, "and when thou liest down, and when thou riseth up".

Text

"I cannot remember everything. I must have been unconscious most of the time.

I remember only the grandiose moment when they all started to sing, as if prearranged, the old prayer they had neglected for so many years – the forgotten creed!

But I have no recollection how I got underground to live in the sewers of Warsaw for so long a time.

The day began as usual: Reveille when it still was dark. "Get out!" Whether you slept or whether worries kept you awake the whole night. You had been separated from your children, from your wife, from your parents. You don't know what happened to them … How could you sleep?

The trumpets again – "Get out! The sergeant will be furious!" They came out; some very slowly, the old ones, the sick ones; some with nervous agility. They fear the sergeant. They hurry as much as they can. In vain! Much too much noise, much too much commotion! And not fast enough! The Feldwebel shouts: "Achtung! Stilljestanden![5] Na wird's mal! Oder soll ich mit dem Jewehrkolben nachhelfen? Na jut; wenn ihrs durchaus haben wollt!" ("Attention! Stand still! How about it, or should I help you along with the butt of my rifle? Oh well, if you really want to have it!")

The sergeant and his subordinates hit (everyone): young or old, (strong or sick), guilty or innocent … .

It was painful to hear them groaning and moaning.

I heard it though I had been hit very hard, so hard that I could not help falling down. We all on the (ground) who could not stand up were (then) beaten over the head … .

I must have been unconscious. The next thing I heard was a soldier saying: "They are all dead!"

Whereupon the sergeant ordered to do away with us.

There I lay aside half conscious. It had become very still – fear and pain. Then I heard the sergeant shouting: "Abzählen!" ("Count off!")

They start slowly and irregularly: one, two, three, four – "Achtung!" The sergeant shouted again, "Rascher! Nochmals von vorn anfange! In einer Minute will ich wissen, wieviele ich zur Gaskammer abliefere! Abzählen!" ("Faster! Once more, start from the beginning! In one minute I want to know how many I am going to send off to the gas chamber! Count off!")

They began again, first slowly: one, two, three, four, became faster and faster, so fast that it finally sounded like a stampede of wild horses, and (all) of a sudden, in the middle of it, they began singing the Shema Yisrael."

| Hebrew (transliterated) | English translation |

|---|---|

| Shema Yisrael, Adonai Eloheinu, Adonai Echad. V'ahavta eit Adonai Elohecha b'chawl l'vav'cha uv'chawl nafsh'cha, uv'chawl m'odecha. V'hayu had'varim haeileh, asher anochi m'tsav'cha hayom, al l'vavecha. V'shinantam l'vanecha, v'dibarta bam b'shivt'cha b'veitecha, uvlecht'cha vaderech, uv'shawchb'cha uvkumecha. Ukshartam l'ot al yadecha, v'hayu l'totafot bein einecha. Uchtavtam, al m'zuzot beitecha, uvisharecha. |

Hear, O Israel, the Lord is our God, the Lord is One. You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, with all your soul and with all your might. And these words which I command you today shall be on your heart. You shall teach them thoroughly to your children, and you shall speak of them when you sit in your house and when you walk on the road, when you lie down and when you rise up. You shall bind them as a sign upon your arm, and they shall be for a reminder between your eyes. And you shall write them upon the doorposts of your house and upon your gates. |

Background

In 1925 Schoenberg was selected to lead a masterclass on composition at the Prussian Academy of Arts by the Minister of Culture Carl Heinrich Becker. After his post was revoked on racist grounds in September 1933, he returned to the Jewish faith he had abandoned in his youth[6] and emigrated to the United States, where he became a professor of composition and, in 1941,[7] an American citizen. The proposal for A Survivor from Warsaw came from the Russian choreographer Corinne Chochem. She sent Schoenberg the melody and English translation of "Partizaner lid" ("Partisan Song")[8] in early 1947 and requested a composition following the Yiddish original or a Hebrew version. Schoenberg requested fees from Chochem "for a 6- to 9-minute composition for small orchestra and choir", and he clarified: "I plan to make it this scene – which you described – in the Warsaw Ghetto, how the doomed Jews started singing, before gooing [sic] to die."[9]

But Schoenberg and Chochem failed to reach a financial agreement, and so the plan to use "Partizaner lid" as the basis of the work had to be abandoned. A commission from the Koussevitzky Music Foundation in Boston, however, offered the composer the opportunity to realize his plan in a modified form.[9] Schoenberg wrote out a text based on an authentic witness account he had heard from a survivor from Warsaw.[10] He began composition on August 11 and completed it in under two weeks on August 23, 1947.[3] Due to poor health, he produced only a condensed score; René Leibowitz, a friend, completed the score under his supervision. The work was dedicated to the Koussevitzky Music Foundation and the memory of Natalie Koussevitzky.

Premiere

The connection between conductor Serge Koussevitzky's foundation and the Boston Symphony Orchestra led to the presumption that he and that orchestra would give the premiere, but Kurt Frederick, conductor of the Albuquerque Civic Symphony Orchestra, had heard about A Survivor from Warsaw and wrote to Schoenberg to ask permission to do the honors, and Schoenberg agreed, stipulating that in lieu of their performance fee the New Mexico musicians should prepare a full set of choral and orchestral parts and send those to him. The premiere was at first scheduled for September 7, 1948, but was delayed until November 4 of that year. Frederick conducted his orchestra at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque[3] with Sherman Smith as narrator. During the two-month delay, Koussevitzsky heard of Frederick's request and approved of the plan.[3]

The premiere was followed by a minute's silence, after which Frederick repeated the whole work; then began a frenzied applause. There were skeptical voices as well. Time magazine wrote:

Cruel Dissonants. First the audience was jolted upright by an ugly, brutal blast of brass. Under it, whispers stirred in the orchestra, disjointed motifs fluttered from strings to woodwinds, like secret, anxious conversations. The survivor began his tale, in the tense half-spoken, half-sung style called Sprechstimme. The harmonies grew more cruelly dissonant. The chorus swelled to one terrible crescendo. Then, in less than ten minutes from the first blast, it was all over. While his audience was still thinking it over, Conductor Kurt Frederick played it through again, to give it another chance. This time, the audience seemed to understand it better, and applause thundered in the auditorium.[11]

A Survivor from Warsaw premiered in Europe on November 15, 1949, in Paris, under the direction of Leibowitz.[12]

Recent performances

As noted in Pierre-Henri Salfati's 2004 documentary La neuvième, at least one performance (the date is not mentioned), "In a tremendous symbolic gesture, the Beethoven Orchestra of Bonn plays Schoenberg's A Survivor from Warsaw and without a pause goes straight into the Ninth Symphony of Beethoven. The Jewish prayer is joined by Beethoven's."[This quote needs a citation] On October 30, 2010, the Berliner Philharmonic under Simon Rattle performed this piece in the same way, leading into Mahler's Second Symphony.[13] The New York Philharmonic, under Alan Gilbert has also performed the piece followed by the Ninth Symphony of Beethoven, in a sequence of five performances were conducted in May 2017 as part of Gilbert's final season as Music Director of the ensemble.[14] Schoenberg's work has also been programmed just before the Mozart Requiem.[citation needed]

Analysis

Richard S. Hill published a contemporary analysis of Schoenberg's use of twelve-tone rows in A Survivor from Warsaw,[15] and Jacques-Louis Monod prepared a definitive edition of the score, later, in 1979.[16] Beat A. Föllmi has since published a detailed analysis of the work's narrative.[17]

Recordings

- RCA LSC-7055: Boston Symphony Orchestra; Erich Leinsdorf, conductor; Sherrill Milnes, narrator; New England Conservatory Chorus, Lorna Cooke deVaron, conductor.

- Columbia SBRG 72119-20: CBC Symphony Orchestra; Robert Craft, conductor[18]

- CBS 76577: BBC Symphony Orchestra; Pierre Boulez, conductor; Günter Reich, speaker

- Naxos 8.557528: Philharmonia Orchestra; Simon Joly Chorale; Robert Craft, conductor; David Wilson-Johnson, narrator

- Deutsche Grammophon 431 774-2: Vienna Philharmonic; Claudio Abbado, conductor; Gottfried Hornik, narrator; Male Choir of the Concert Chorus of the Vienna State Opera

References

- ^ Schiller, David Michael. Bloch, Schoenberg and Bernstein: Assimilating Jewish Music. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

- ^ Schmitt, Karolin (2011). We should never forget this. Holocausterinnerungen am Beispiel von Arnold Schönbergs 'A Survivor from Warsaw' op. 46 im zeitgeschichtlichen Kontext ["We should never forget this": Holocaust memories through the example of Arnold Schoenberg's "A Survivor from Warsaw" op. 46 in the contemporary historical context] (MA).

- ^ a b c d Strasser, Michael (February 1995). "A Survivor from Warsaw as Personal Parable". Music & Letters. 76: 52–63. doi:10.1093/ml/76.1.52.

- ^ Kundera, Milan (2010). "Encounter". p. 151.

- ^ According to original text: Gramann, Heinz (1984). Die Ästhetisierung des Schreckens in der europ. Musik des 20. Jhds [The Aestheticization of terror in the European music of 20th century] (PDF) (in German). Verlag für systematische Musikwissenschaft. p. 201. Retrieved 30 January 2023.

- ^ Schönberg. Briefe. p. 182.[full citation needed]

- ^ Kuiper, Kathleen; Newlin, Dika. "Arnold Schoenberg". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Amy Lynn Wlodarski, Musical Witness and Holocaust Representation, 2015, ISBN 1107116473, p. 14

- ^ a b Therese Muxeneder. "A Survivor from Warsaw for narrator, men's chorus, and orchestra, Op. 46". Arnold Schönberg Center. Retrieved 16 July 2022.

- ^ Feezell, Mark. "The Lord Our God Is One: Form, Technique, And Spirituality in Arnold Schoenberg's A Survivor from Warsaw, Op. 46" (PDF). Retrieved 13 May 2017.

- ^ "Destiny & Digestion". Time. No. 20. 15 November 1948. p. 56. Retrieved 13 May 2017.

- ^ Hartmann, Bernhard (1998-12-31). "Das Entsetzliche wird Klang". General-Anzeiger (in German). Bonn. Retrieved 2017-05-13.

- ^ "Sir Simon Rattle conducts Mahler's Symphony No. 2". Digital Concert Hall. Retrieved 18 December 2017.

- ^ "Ode to Joy: Beethoven Symphony No. 9". nyphil.org. Retrieved 18 December 2017.

- ^ Richard S. Hill, "Music Reviews: A Survivor from Warsaw, for Narrator, Men's Chorus, and Orchestra by Arnold Schoenberg" (December 1949). Notes (2nd series), 7 (1): pp. 133–135.

- ^ Richard G. Swift, Review of newly revised edition of Arnold Schoenberg, A Survivor from Warsaw (September 1980). MLA Notes, 37 (1): p. 154.

- ^ Föllmi, Beat A. (1998). "'I Cannot Remember Ev'rything'. Eine narratologische Analyse von Arnold Schönberg's Kantate A Survivor from Warsaw op. 46". Archiv für Musikwissenschaft (in German). LV (1): 28–56. doi:10.2307/930956. JSTOR 930956.

- ^ Edward Greenfield, "Gramophone Records" (review of Schoenberg, Complete Works, Vol. 1) (1963). The Musical Times, 104 (1448): p. 714.

Further reading

- Calico, Joy. Arnold Schoenberg's A Survivor from Warsaw in Postwar Europe. University of California Press, Berkeley, 2014. ISBN 9780520281868.

- Eichler, Jeremy, Time's Echo: The Second World War, the Holocaust, and the Music of Remembrance, Faber & Faber, London, 2023. ISBN 9780571370535.

- Kamien, Roger. Music: An Appreciation, 6th brief edition, New York, 2008, pp. 325–327.. ISBN 0-07-340134-X.

- Offergeld, Robert. Beethoven – Symphony no. 9 – Schoenberg – A Survivor from Warsaw, included booklet. BMG Classics 09026-63682-2, New York, 2000.

- Schoenberg, Arnold. Style and Idea. University of California Press, Los Angeles, 1984. ISBN 0-520-05294-3