Wang Ximeng

Wang Ximeng (Chinese: 王希孟; pinyin: Wáng Xīmèng', 1096–1119) was a Chinese painter during the Northern Song period, in the early twelfth century. A prodigy,[1] Wang was a student at the imperial court's school of paintings, where he was noticed by Emperor Huizong of Song, who saw Wang's talent and personally taught him. In 1113, at the age of 18, he created his only surviving work, a long blue-green scroll called A Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains. He died at the age of 23.

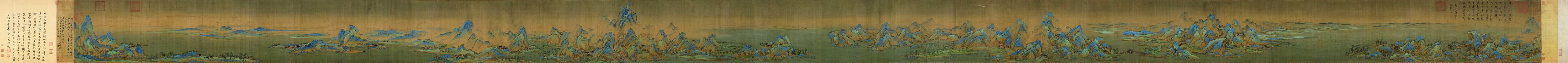

The painting has since been called a masterpiece of Chinese art; the scroll is in the permanent collection of the Palace Museum in Beijing. The scenery in the painting was later identified as Mount Lu and Poyang Lake in Jiujiang.[2][3]

Biography

Eighteen-year-old [Wang] Ximeng is a student at the Painting School with an appointment in the Documents Store house. He submitted his paintings to Huizong, who considered them not yet very accomplished. Still His Majesty recognized Wang's aptitude and thought he might be teachable. He began to instruct him personally in technique. In less than half a year, Wang submitted this painting, which the emperor thought very fine. He then conferred it on me.

Wang Ximeng (Chinese: 王希孟; pinyin: Wáng Xīmèng', 1096–1119) was a Chinese painter during the Song Dynasty, Northern Song period, in the early twelfth century. Wang was a student of the court Painting School, where he was noticed by Emperor Huizong of Song, who saw Wang's talent and taught him. In 1113, at the age of 18, he created his only survived work, A Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains.[5] He died at the age of 23.[6]

A Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains

Wang's only surviving work is a long scroll titled A Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains (千里江山圖).[7][8] The painting, finished by Wang when he was only 18 in 1113, has been described as one of the greatest works of Chinese art.[9] It is in the permanent collection of the Palace Museum in Beijing.[5] The scroll's size is 51.5 by 1191.5 cm.[5]

The scroll contains a postcript written by Cai Jing that is dated to 1113.[10]

The scroll was acclaimed by Emperor Huizong, who "bestowed" it to Cai Jing, who wrote about the artist at the end of the scroll. When Cai Jing was demoted, the scroll was lost; it reappeared later in the collection of Emperor Lizong of the Southern Song dynasty. Later it was part of the Liang Qingbiao's "Studio of Plantain Grove" collection; then it became part of the Emperor Qianlong's collection, and "was illustrated in The Precious Collection of the Stone Canal Pavilion (Shiqu baoji), an extensive catalogue of painting and calligraphy in the imperial collection". Pu Yi, the Last Emperor of China, gave the scroll to his brother Pu Jie in 1922, who relocated it from the palace to the "Xiaobailou" in Changchun. After the Second Sino-Japanese War, the work reappeared on the market and was bought by antique dealer Jin Bosheng. In 1953 it was added to the permanent collection of the Palace Museum (Beijing).[8]

The painting throughout history has been lauded by many. Monk Fuguang, a painter from the Yuan dynasty, wrote about it: "Since I was eager to learn from others, I have witnessed this painting for nearly a hundred times. I cannot still look through all the details in this work because I can always find some new information. And it has bright colors and magnificent layout, which may make Wang Jinqing and Zhao Qianli ashamed when seeing this marvelous painting. Among all the paintings on green landscapes, this work can be unique and the leader for thousands of years."[10]

The scroll was done in the blue-green landscape technique of the Sui and Tang dynasties,[5] using azurite and malachite colours.[8] Zhan Ziqian of Sui, Li Sixun and Li Zhaodao, Zhang Zao, and Wang Wei of Tang are famous painters who worked in this genre. In the time of Emperor Huizong, blue-green paintings became a medium used to "express literary ideals".[8] Wang Ximeng apparently "boldly blended the north and south style" in his work.[10] With time the silk became darker, but colours are still bright.[10] Patricia Buckley Ebrey writes about Wang's style that the choice of blue and green colours can be seen as "a gesture of respect for the past"; besides colours, he borrows other Tang dynasty features - carefully drawn lines, and "perhaps the decision to feature people traveling through the landscape on foot, on horse back, and in boats". She notes that his compositional methods are "entirely" Song: "mountains and trees are not outlined, the hills are volumetric, and the lighting effects are dramatic".[6] Yuan dynasty Grand Secretariat Pu Guang wrote that the scroll is "a unique piece over a thousand years, comparable to the lone moon in a sky of stars".[8]

Wang Ximeng used typical technique of multiple perspectives, painting mountainous landscapes "naturally separated into six sections by bridges and water". Mountains were described as being "in the style of Southern China"; it can indicate that Wang Ximeng was from that region.[5]

The painting was interpreted variously during its history. Murck writes that the scroll is a "superb visualization of the concept of 'a great lord glorious on his throne and a hundred princes hastening to pay him court'";[11] Yurong Ma writes that the painting "can express the image of peaceful world: the distribution of mountains and forests reflects the order between an emperor and courtiers, gentlemen and snobs; the mountain landscape is endless and steep, but it does not show the pass of the city defense, but emphasizes the leisurely elegance of the scholars and the livelihood of the people; the clear water and the blue waves are not only the performance of the season, but also the symbol of peace."[10] He also compared the work to a symphony, divided into six parts: "section, prelude, rise, development, climax, fall and end. The mountain in the painting is running for thousands of miles, with high and low levels, and contains a strong sense of rhythm and order. When creating this work, Wang Ximeng obviously applied midpoints, lines, and faces in calligraphy to compose works with a sense of musical rhythm and bring new life to the paintings."[10]

Notes

- ^ Murck 2000, p. 123.

- ^ ""A Thousand Miles of Rivers and Mountains" actually has a real scene, and the prototype of the landscape is here". iNEWS. Retrieved 20 January 2023.

- ^ "专家解密《千里江山图》:取景庐山和鄱阳湖-浙江新闻-浙江在线". zjnews.zjol.com.cn.

- ^ Ebrey 2014, p. 186.

- ^ a b c d e "A Panorama of Rivers and Mountains - The Palace Museum". en.dpm.org.cn. Retrieved 29 November 2022.

- ^ a b Ebrey 2014, pp. 214–216.

- ^ Barnhart 1997, pp. 124–125.

- ^ a b c d e "Apophrades of Genius: The Ascent of Zhang Daqian's Landscape after Wang Ximeng". sothebys.com. Retrieved 29 November 2022.

- ^ Caradog Vaughan James (1989). Information China: the comprehensive and authoritative reference source of new China, Volume 3. Oxford: Pergamon Press. p. 1114. ISBN 0-08-034764-9.

- ^ a b c d e f Ma 2021.

- ^ Murck 2000, p. 123.

References

- Barnhart, Richard M., ed. (1997). Three thousand years of Chinese painting. New Haven : Yale University Press ; Beijing : Foreign Languages Press. ISBN 978-0-300-07013-2.

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley (2014). Emperor Huizong. Cambridge, Massachusetts. ISBN 978-0674725256.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Murck, Alfreda (2000). Poetry and Painting in Song China: The Subtle Art of Dissent. Harvard Univ Asia Center. p. 123. ISBN 978-0-674-00782-6.

- Ma, Yurong (2021). "Study on "A Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains" by Wang Ximeng". Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Arts, Design and Contemporary Education (ICADCE 2020). pp. 63–66. doi:10.2991/assehr.k.210106.013. ISBN 978-94-6239-314-1. S2CID 234242592. Retrieved 6 December 2022.