Buson yōkai emaki

The Buson yōkai emaki (蕪村妖怪絵巻) is an 18th century collection of "picture scrolls" (絵巻, emaki) depicting Japanese yōkai by poet and painter Yosa Buson. The whereabouts of the original work are presently unclear; its contents are known from a reprinting released by the Kitada Shisui Collection in 1928.[2]

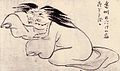

It is thought that the collection was made during the period between 1754 and 1757, when Buson was studying painting in Miyazu, Tango Province, at the Kenjōji (見性寺) temple.[3] In total, eight different kinds of yōkai (妖怪) are depicted. Some of the works are annotated with just the name of the being portrayed, whereas others include a more detailed story. It has been surmised that, whilst Buson was travelling across Japan, he picked up various stories about different kinds of regional yōkai, and that the yōkai emaki contains his realisation of those stories.[2][4]

Buson, who excelled in the haiga-style, forsook realism, and instead painted his yōkai in a manner that uniquely resembles modern Japanese manga.[2][4] Most traditional paintings of yōkai from Japan's mediaeval period (1185–1568) portrayed them as supernatural beings, the fearful harbingers of disaster, but works from the Edo period (1603–1868), including Buson's, paint them as familiar, funny, creatures that can be enjoyed as fiction. This trend continues in modern yōkai manga, which have their origins in Edo period works like Buson's.[2]

Excerpts of the emaki

-

"Bakeneko of the Sasakibara Family"

-

"Akago no kai"

-

"The Noppera-bō of Kyoto"

-

"The yonakibabā of Enshū"

References

- ^ Chiang, Howard (1 July 2015). Historical epistemology and the making of modern Chinese medicine. Oxford University Press. p. 77. ISBN 9781784991913.

- ^ a b c d Hyōgo Prefectural History Museum; Kyōto International Manga Museum (2009). 図說妖怪画の系譜 [Zusetsu Yōkaiga no keifu] (in Japanese). Tokyo: Kawade Shobō Shinsha. pp. 12–14. ISBN 9784309761251.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Tanigawa, Ken'ichi, ed. (1987). 日本の妖怪. [Nihon no yōkai.]. 別冊太陽 [Bessatsu taiyō] (in Japanese). Heibonsha. pp. 112–113.

- ^ a b Yumoto, Kōichi (2003). 妖怪百物語絵卷 [Yōkai hyaku monogatari emaki] (in Japanese). Tokyo: Kokusho Kankōkai. p. 122.