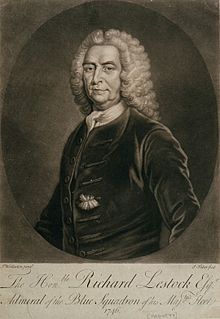

Richard Lestock

Richard Lestock | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 22 February 1679 |

| Died | 17 December 1746 (aged 67) Possibly either Portsmouth or London |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1701–1746 |

| Rank | Admiral of the Blue |

| Commands | HMS Vulture HMS Fowey HMS Weymouth HMS Panther HMS Princess Amelia HMS Royal Oak HMS Kingston HMS Somerset HMS Grafton HMS Boyne HMS Neptune Portsmouth Station Mediterranean Fleet |

| Battles / wars | Battle of Vélez-Málaga Battle of Toulon (1707) Battle of Cape Passaro Battle of Cartagena de Indias Battle of Toulon (1744) |

Richard Lestock (22 February 1679 – 17 December 1746) was an officer in the Royal Navy, eventually rising to the rank of Admiral. He fought in a number of battles, and was a controversial figure, most remembered for his part in the defeat at the Battle of Toulon, and the subsequent court-martial.

Family and early years

Lestock is believed to have been born on 22 February 1679, though he may have been born some years previously. He was the second son of Richard Lestock (d. 1713) and his wife, Rebecca (d. 1709). His father had been magistrate for Middlesex, and commander of a number of merchant ships. On 26 December 1690, the father was among those invited by the Admiralty to volunteer for naval service, which he did. On 6 January 1691 Lestock's father was appointed to command HMS Cambridge.[1]

Lestock followed his father into the navy. In April 1701 he was appointed third lieutenant to the Cambridge.[2] A number of postings to different ships then followed, to HMS Solebay, HMS Exeter and then HMS Barfleur. The Barfleur was at this time the flagship of Sir Cloudesley Shovell. Lestock was present with Shovell at the Battle of Vélez-Málaga. Shovell then promoted him to his first command, and in August 1705 Lestock became master and commander of the fire ship HMS Vulture. Whilst in command of her, he was active ashore at the relief of Barcelona and the capture of Alicante.[3]

Captain of the Fowey and the Panther

Lestock took over the command of the 32-gun HMS Fowey on 29 April 1706, and was sent home in September with the news of the surrender of Alicante. On his return he was among those who helped to destroy a 64-gun French warship off Almeria in December that year. He was then ordered to join with Sir George Byng to assist the ground forces in the failed attack on Toulon in 1707. Lestock and the Fowey were then present at the capture of Menorca the following year. The Fowey was sailing from Alicante to Lisbon in April 1709, when on 14 April she was overhauled by two enemy 40-gun frigates. A two-hour battle ensued, after which the outgunned Fowey was forced to surrender. Lestock was exchanged shortly after and returned to England, where he faced a court-martial for the loss of his ship. He was fully acquitted on 31 August 1709.[3]

His next appointment was to command HMS Weymouth in the West Indies, which he did from 1710 until 1712. When she was paid off (decommissioned), Lestock went to half pay for five years, before he finally received command of HMS Panther in the Baltic in 1717. The fleet he joined was under George Byng, whom he had served with before. Lestock was given command of a seven-ship squadron, and ordered to cruise off Göteborg and in the Skagerrak, operating against Swedish privateers. Lestock seems to have made a favourable impression, and Byng made him second captain aboard his flagship, the Barfleur, during the Battle of Cape Passaro in 1718.[3]

Career stalled

Despite impressing so highly influential an admiral, Lestock remained on half pay for nearly ten years. He returned to active duty only in 1728, commanding HMS Princess Amelia. He moved the next year to join HMS Royal Oak, and served aboard her in the Mediterranean in 1731 under Sir Charles Wager. He took up his next command, that of HMS Kingston on 21 February 1732 and received orders on 6 April to wear a red broad pennant and prepare to sail to the West Indies to take up the post of commander-in-chief of the Jamaica Station.[4] Contrary winds however stopped him sailing until 29 April. Three weeks later Sir Chaloner Ogle was appointed commander-in-chief at Jamaica instead, and a letter was written ordering Lestock to strike his flag and return to Britain. No reason was given. Lestock was dismayed by this snub, writing in a letter from Port Royal on 21 November:

My affair being without precedent I cannot say much, but such a fate as I have met with is far worse than death, many particulars of which I doubt not will be heard from me when I shall be able to present myself to my lords of the admiralty.[5]

Further humiliation followed when he was twice passed over for flag-rank in 1733 and again in 1734. During this period five captains of lesser seniority were promoted. Despite this apparent stalling of his career, Lestock continued in active service. He was appointed captain of HMS Somerset on 22 February 1734,[3] the Somerset then stationed as guard ship in the Medway. He served aboard her until April 1738, then moving to HMS Grafton, stationed at the Nore.[3] During his time here he was noted for being occasionally overly zealous in arresting vessels that had no right to wear an official pendant. He was made captain of HMS Boyne in August 1739, and accompanied Sir Chaloner Ogle to the West Indies the following year.[3]

Return to prominence

Whilst in the West Indies, Vice-Admiral Edward Vernon appointed him commodore and third in command of the fleet. Lestock regularly attended Vernon's naval councils of war. During the Battle of Cartagena de Indias he was appointed to command the attack on Fort San Luis on 23 March 1741. The battle ended in defeat and the Boyne was severely damaged. Lestock returned to England in the summer aboard the Princess Carolina. He then took over the command of HMS Neptune and was appointed Commander-in-Chief Mediterranean Fleet and sent out with a large contingent of reinforcements in November 1741.[6]

Bad weather contrived to delay the sailing for several weeks, and he was unable to join Vice-Admiral Nicholas Haddock's fleet until the end of January 1742. By this time, the ships had been badly damaged by the weather, and many of the crew were ill or had died. Nevertheless, Lestock was promoted to rear-admiral on 13 March 1742. Haddock was forced to return to England a couple of months later due to ill health, leaving Lestock as acting commander-in-chief. Lestock hoped to have the appointment confirmed from England, but was bitterly disappointed to learn that Vice-Admiral Thomas Mathews had been dispatched to take over command.[3]

Relations with Mathews

The two men had already worked together. Mathews had been commissioner at Chatham during the period Lestock had been in charge of the guard ships. Mathews arrived and took over command, and began to openly criticise Lestock's performance. He also countermanded his appointments. Mathews was much occupied with the diplomatic duties of his position and relied on Lestock to manage the fleet, but became increasingly resentful of Lestock's inability to do his job owing to his poor health. Despite sending complaints back home, Lestock was promoted to vice-admiral of the white on 29 November 1743 and remained as Mathews' second.[3]

The Battle of Toulon

It was whilst the two were on the Mediterranean station that the Battle of Toulon was fought on 11 February 1744. The British fleet attempted to engage a Spanish convoy, with Lestock taking command of the Rear division. The battle ended in failure for the British. Lestock was accused of adhering to a restrictive interpretation of the fighting instructions and for a failure to take the initiative, so contributing to the failure. The British had been following the Spanish the previous day, but on the evening of 10 February Lestock halted the rear before it had reached its proper position in line abreast. By morning they had drifted even further out of line, eventually lying some five miles distant of the rest of the fleet. Only then did Lestock attempt to reach the action, but arrived too late.[3]

Mathews had been making signals all morning, and had twice sent a lieutenant in a boat to urge Lestock to bring his ships into the battle. Lestock replied that he was doing all he could, but that some of his ships were slow. He did not however order his faster ones forwards, nor did he follow Mathews' signal to engage, allowing four lagging Spanish ships to slip away from him. After the action Lestock argued that the signal for the line was still flying, which he saw as his primary duty to obey. He would only therefore follow the signal to engage when he could do so from his position in the line. When challenged why he had allowed such a gap to open between the rear and the rest of the fleet the previous night, Lestock claimed that the rules required him to follow the signal to ‘bring to’ the moment it was given, this taking precedence over the signal to move to line abreast. These interpretations were highly dubious, and failed to satisfy Mathews. He suspended Lestock and sent him home.[3]

The action is debated

On his return, Lestock began to cast blame on Mathews and other captains that had not served in his division. A pamphlet war ensued, but high and low opinion was against him. Lestock did have important political friends though, and they managed to obtain a parliamentary inquiry into the outcome. This took place in the House of Commons over a number of days between March–April 1745, and sharply divided public opinion. Anti-Mathews speeches were made by Henry Fox and George Grenville, whilst Lestock himself impressed the MPs with his cool, calm demeanour. Mathews' defence in comparison was seen as heated and disorganized, just as how Lestock claimed Mathews had fought the battle. Mathews was also viewed with suspicion by the naval authorities, who were wary of his ‘out of doors’ popularity. The Admiralty Board convened a court-martial made up of officers sympathetic to Lestock, who was acquitted of any wrongdoing.[3]

Controversy over the judgement

The outcome failed to convince the wider population. A later naval historian wrote in 1758 that:

‘the nation could not be persuaded that the vice-admiral ought to be exculpated for not fighting’ and the admiral cashiered for fighting[7]

The evidence of the court-marital was not released and confusion over the true events persisted for some time. Robert Beatson decided that Lestock

‘shewed a zeal and attention which gives a very advantageous idea of his capacity as a seaman and an officer’[8]

whilst John Campbell declared in his Lives of the British Admirals that Lestock ‘ought to have been shot’.

Public opinion remained divided, but a song written in the earlier nineteenth century about the heroism of Richard Avery Hornsby, entitled Brave Captain Hornsby references Lestock, depicting him as betraying his friends:

There is an old proverb I've lately thought on,

When you think of a friend you're sure to find none';

For when that I thought to see Lestock come by,

He was five miles a distance, and would not come nigh;[9]

Return to service and last days

On 5 June 1746, just two days after his acquittal he was promoted admiral of the blue [10] and given command of a large squadron. The original plan called for the launching of an assault on Quebec, but an attack on the French port of Lorient was decided instead. Despite planning difficulties, the force was landed and nearly succeeded in taking the city. The result was ultimately a failure and was viewed as such by a disappointed public, but Lestock appears to have acquitted himself well. He hoped to receive an appointment to command a spring expedition to North America, but his health suddenly declined, and he died of a stomach ailment on 13 December 1746.[3]

Family and personal life

Lestock probably married Sarah (d. 1744), of Chigwell Row in Essex during his time on half pay in the early 1720s. They may have had a son, as a boy named Richard Lestock was baptised at Chigwell on 14 July 1723, but if so he presumably died young as no more is heard about him.[11] The couple also had a daughter, Elizabeth, who survived her father. In addition, Lestock promoted a man named James Peers to the command of the Kingston at Jamaica on 26 August 1732. Peers was apparently spoken of as Lestock's son-in-law; however there was no mention of him in Sarah's will.[3]

His wife predeceased him on 12 September 1744. Their daughter married James Peacock, a purser in the navy. Lestock seems to have been on bad terms with his family, leaving all of his property to an apothecary, William Monke of London. He also left a bequest to his friend Henry Fox, who had been one of those defending him in the Commons.[3]

References

- ^ "HMS Cambridge". Three Decks. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- ^ Harrison, Simon (2010–2018). "Richard Lestock (1678/79-1748)". threedecks.org. S. Harrison. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

- ^ Cundall, p. xx

- ^ (National Archives of the United Kingdom, Public Record Office, London, ADM 1)

- ^ Bruce, Anthony; Cogar, William (2014). Encyclopedia of Naval History. Cambridge, England: Routledge. p. 240. ISBN 9781135935344.

- ^ The Naval History of Great Britain, 4 vols., 1758, 4.270

- ^ Beatson, 1.220

- ^ Naval songs and ballads

- ^ Harrison, Simon (2010–2018). "Richard Lestock (1678/79-1748)". threedecks.org. S. Harrison. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - ^ History of Chigwell

Sources

- Cundall, Frank (1915). Historic Jamaica. West India Committee.