Metapleural gland

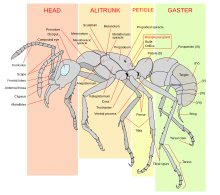

Metapleural glands (also called metasternal or metathoracic glands) are secretory glands that are unique to ants and basal in the evolutionary history of ants. They are responsible for the production of an antibiotic fluid that then collects in a reservoir on the posterior of the ant's alitrunk. These reservoirs are also referred to as the bulla and vary in size between ant species and also between castes of the same species.[1]

From the bulla, ants can groom the secretion onto the surface of their exoskeleton. This helps to prevent the growth of bacteria and fungal spores[2] on the ants and inside their nest.[3][4]

Though considered an important component in an ant's immunity against parasites, some ant species have lost the gland during their evolution. These losses correlate with ants that have a 'weaving' lifestyle,[5] such as ants in the genus Oecophylla, Camponotus and Polyrhachis. It was originally suggested that because this weaving lifestyle also tended to involve an arboreal lifestyle that the parasite pressure above ground was not as great as for terrestrial ants, resulting in a reduced selective pressure to keep this antibiotic gland. Recent work suggests instead that these ants may just use other antiparasite defences such as increased grooming and venom.[2]

Most male ants are not known to have metapleural glands. It is believed that they benefit from the shared secretions of other ant workers and do not need any themselves.[6] Additionally, slave-making ants do not have metapleural glands though the slave species they use do and it is these ants that groom the slavemakers and their brood.[6]

References

- ^ Bert Hölldobler (1984). "On the metapleural gland of ants" (PDF). Psyche. 91 (3–4): 201–224. doi:10.1155/1984/70141.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Peter Graystock; William O. H. Hughes (2011). "Disease resistance in a weaver ant, Polyrhachis dives, and the role of antibiotic-producing glands". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 65 (12): 2319–2327. doi:10.1007/s00265-011-1242-y.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Andrew J. Beattie; Christine Turnbull; Terryn Hough; Sieglinde Jobson; R. Bruce Knox (1985). "The vulnerability of pollen and fungal spores to ant secretions: evidence and some evolutionary implications". American Journal of Botany. 72 (4): 606–614. doi:10.2307/2443594.

- ^ D. Veal, Jane E. Trimble & A. Beattie (1992). "Antimicrobial properties of secretions from the metapleural glands of Myrmecia gulosa (the Australian bull ant)". Journal of Applied Microbiology. 72 (3): 188–194. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2672.1992.tb01822.x.

- ^ Rebecca N. Johnson, Paul-Michael Agapow & Ross H. Crozier (2003). "A tree island approach to inferring phylogeny in the ant subfamily Formicinae, with especial reference to the evolution of weaving" (PDF). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 29 (2): 317–330. doi:10.1016/S1055-7903(03)00114-3. PMID 13678687. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-04-06.

- ^ a b Bert Hölldobler & Edward O. Wilson (1990). The Ants. Berlin: Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-52092-4.