Jean Joseph Marie Amiot

Jean Joseph Marie Amiot | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1 February 1718 |

| Died | 9 October 1793 (aged 75) |

Jean Joseph Marie Amiot (sometimes Amyot; Chinese: 錢德明; pinyin: Qián Démíng; February 1718 - October 9, 1793) was a French Jesuit missionary in Qing China, during the reign of the Qianlong Emperor.

Life

Joseph Marie Amiot was born at Toulon. He entered the Society of Jesus in 1737 and was sent in 1750 as a missionary to China. He soon won the confidence of the Qianlong Emperor and spent the remainder of his life at Beijing. He was a correspondent of the Académie des Sciences, official translator of Western languages for the Qianlong Emperor, and the spiritual leader of the French mission in Peking.[1] He died in Peking in 1793, two days after the departure of the British Macartney Embassy. He could not meet Lord Macartney, but exhorted him to patience in two letters, explaining that "this world is the reverse of our own".[2] He used a Chinese name (錢德明) while he was in China.

Works

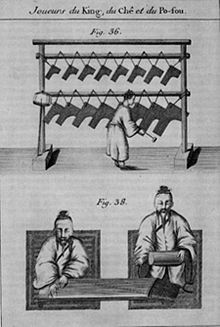

Amiot made good use of the advantages which his situation afforded, and his works did more than any before to make known to the Western world the thought and life of the Far East. His Manchu dictionary Dictionnaire tartare-mantchou-français (Paris, 1789) was a work of great value, the language having been previously quite unknown in Europe. In 1772 he translated The Art of War, one of the most influential war strategy and tactics treatises in military history, written around the 6th century BCE and attributed to General Sun Tzu, into French. The first successful translation to English would not be achieved before another 138 years, in 1910. His other writings are to be found chiefly in the Mémoires concernant l'histoire, les sciences et les arts des Chinois (15 volumes, Paris, 1776–1791). The Vie de Confucius, the twelfth volume of that collection, was more complete and accurate than any predecessors.

Amiot tried to impress mandarins in Beijing with Rameau's harpsichord piece Les sauvages,[3] a suite that was later reworked as part of Rameau's opera-ballet Les Indes galantes. Amiot was the first European to comment on the Chinese yo-yo.[4] Amiot was the first European to ship free-reeded instruments from the orient to Europe. The introduction of the sheng was to set off an era of experimentation in free-reeded instruments that would ultimately lead to the invention of the harmonica.[5]

See also

References

Citation

- ^ Alain Peyrefitte, "Images de l'Empire Immobile", p. 113.

- ^ Alain Peyrefitte, p. 113.

- ^ Thomas Christensen, "Rameau and Musical Thought in the Enlightenment", Cambridge University Press, 1993. ISBN 0-521-42040-7. Page 295. On Google Books

- ^ Duckett, M. W.; ed. (1861). "Diable", Dictionnaire de la conversation et de la lecture inventaire raisonné des notions générales les plus indispensables à tous par une société de savants et de gens de lettres sous la direction de M. W. Duckett ["Dictionary ... under the direction of M. W. Duckett"], Volume 7, p.531-2. 2nd edition. F. Didot. (in French)

- ^ "Indes galantes, Les (The Gallant Indies," Naxos.com website (accessed 9 March 2010)

Sources

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Amiot, Jean Joseph Marie". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Further reading

- Ching Wah LAM, "A Highlight of French Jesuit Scholarship in China: Jean-Joseph-Marie Amiot's Writings on Chinese Music", CHIME, Journal of European Foundation for Chinese Music Research, Leiden, 2005, 16-17: 127–147.

- Jim LEVY, "Joseph Amiot and Enlightenment Speculation on the Origins of Pythagorean Tuning", "THEORIA, University of North Texas Journal of Music Theory", Denton, 1989, 4: 63-88