Ink blot test

This article has an unclear citation style. (May 2018) |

| Ink Blot Test | |

|---|---|

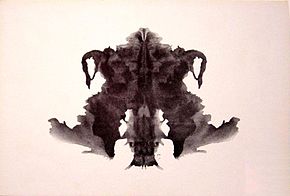

The fourth blot of the Rorschach test | |

| MeSH | D007282 |

An ink blot test is a personality test that involves the evaluation of a subject's response to ambiguous ink blots. This test was published in 1921 by Hermann Rorschach who was a psychiatrist from Switzerland. The interpretation of people's responses to the Rorschach Inkblot Test was originally based on psychoanalytical theory but investigators have used it in an empirical fashion. When this test is used empirically, the quality of the responses is related to the measurements of personality.[1]

Throughout the 1940s and 1950s the ink blot test was popular among clinical psychologists but quickly lost popularity as critics claimed it to be too subjective. Variations of the ink blot test have since been developed such as the Holtzman Inkblot Test and the Somatic Inkblot Series.[2]

An ink blot test is a general category of projective tests. In projective tests, participants' interpretations of ambiguous stimuli are used to analyze inner thoughts, feelings, and personality traits. In the 19th century, ink blots were actually used for a game called "Blotto".[3] There are also tests that were developed to be used in clinical, organizational, and human resource departments.[4] These projective tests are often organized in a taxonomy using the categories: Association, Construction, Completion, Arrangement, and Expression.[5]

Herman Rorschach created the first systematic ink blot test of its kind in the early 1920s that interpreted personality characteristics of subjects taking the test.[6] His test was widely popular but also critiqued. After his death, multiple other Ink Blot tests were formed. Some of these new tests include: The Howard Ink Blot Test, Holtzman inkblot technique, and Rorschach II Ink Blot Test.

Under the guidance of Rorschach, Hans Behn-Eschenburg developed 10 similarly designed inkblots to Rorschach's in 1920. Both men died before being able to develop a guide as how to measure, score, and diagnose off of either versions of the ink blot tests.

History

Ink blots inspired artists such as Leonardo Di Vinci and Victor Hugo in the 15th and 19th centuries.[7] Alfred Binet also suggested using ink blots to assess visual imagination.[8] Although the Rorschach test was widely used, its popularity died down because controversy over the validity of the test measurements. Herman Rorschach never intended for the ink blot to be a sole assessment of personality, however some psychologists may have tried to use it as such. Many people thought the measurement of responses were too subjective which led psychologists to come up with a better way of measuring responses after Rorschach's death. For example, Holtzman inkblot technique was seen as less controversial, because the developers took previous criticism into consideration and aimed to make their test better. Another variation of the Rorschach test is the Howard Ink Blot Test. This test was aimed at group measurements of personality rather than an individual measurement.[9] While these tests were seen to have improved validity of ink blot tests, psychologists are still skeptical which lead to the fallout of these projective tests.

Procedure

The procedure for administration and measurement varies by each ink test, however, they are all based around how the participant responds to ambiguous stimuli. The Howard ink blot test for example, has participants responding to one card at a time with the ink blots on it. They are then told to tell the psychologist everything they see and what it might represent to them. Time of responses from start to finish is also measured with this test.[10] For the Rorschach test, subjects are sitting side by side with the researcher and is presented with the 10 official ink blot cards one at a time. After they have all been presented once, and the participant has responded, the cards are presented again and the participant is told to rearrange the cards to match what they saw the first time. The researchers watching monitor every movement and everything the participant says aloud as well and records it.[11] This is a lot different from the Howard test because the cards are re-presented to the participants. Tests like the Blacky pictures test and the Thematic apperception test involve making up narratives for the pictures presented to the participants. Based on these narratives, psychologists can assess personality and unconscious thoughts and motives. While all these projective tests have different procedures and types of measurement, they are all thought to measure one's personality, one's thoughts and one's emotions; including those that are from the unconscious mind of the participant. Dr. Rakesh Kumar wrote a book Rorschach Inkblot Test: A Guide to Modified Scoring System, which is his interpretation on how to administer, score, and diagnose based on the ink blot tests.

Applications

These tests were developed to be used in clinical, organizational, and human resource departments.[12] Some psychologists might still use these tests today for personality assessments or assessments of unconscious motives or feelings. However, the American Psychological Association discourages use of official ink blot tests.[13] Because of the early and untimely death of both of these men, resulting in the lack of a key to reading the answers given by patients, psychologists have been skeptical of using the ink blots as a reliable source in clinical work. Many studies have been conducted trying to deduce an answer to whether or not to use the ink blots. An overview of past ink blot studies, found that the ink blots do show a tendency towards certain data but there is a lack of research and evidence actually using the ink blots clinically.

Psychologists who use projective tests, like the ink blot test, argue that they are useful at tapping into underlying thoughts and desires that not even the patient is aware that they are having.[14] A projective test requires a highly trained psychologist to analyze the data and determine what it means, this would leave room for criticism. Projective tests, such as the Rorschach test have been criticized due to issues with inter-rater reliability, test-retest reliability (repeatability), validity, biases, and issues with cultural sensitivity and norms.[15]

One advantage of projective tests is that individuals taking the test are free to answer however they see fit. Since projective tests are subjective, participants don't have any constraints on how they answer. The subjectivity of these tests is why psychologists thought that it measured one's most inner thoughts and feelings and/or ones personality. The more unstructured stimuli, the more the participant reveals about themselves.[16] This contrasts with objective tests where the answers are clearly put into categories and participants are very limited in how they can answer. While objective tests can still measure emotions, thoughts, and personality, the answers are already pre-set thereby limiting the answers of the participant. This in theory, would hinder the process of stating one's most inner thoughts & feelings. Another advantage is the ambiguity of the projective tests makes the purpose of the test unknown. This is an advantage because if participants know what they are being tested for, they are more likely to socially conform and mask their true answers.[17]

See also

References

- ^ Carlson, N. R., & Heth, C. (2010). Psychology--the science of behaviour, fourth Canadian edition [by] Neil R. Carlson, C. Donald Heth. Toronto: Pearson.

- ^ [1], "Rorschach Inkblot Test", Retrieved October 22, 2014.

- ^ Hubbard, K., & Hegarty, P. (2016). Blots and All: A History of the Rorschach Ink Blot Test in Britain. Journal Of The History Of The Behavioral Sciences, 52(2), 146-166.

- ^ Lilienfeld, S. O., Wood, J. M., & Garb, H. N. (2000). The scientific status of projective techniques. Psychological science in the public interest, 1(2), 27-66.

- ^ Lilienfeld, S. O., Wood, J. M., & Garb, H. N. (2000). The scientific status of projective techniques. Psychological science in the public interest, 1(2), 27-66.

- ^ Hubbard, K., & Hegarty, P. (2016). Blots and All: A History of the Rorschach Ink Blot Test in Britain. Journal Of The History Of The Behavioral Sciences, 52(2), 146-166.

- ^ Hubbard, K., & Hegarty, P. (2016). Blots and All: A History of the Rorschach Ink Blot Test in Britain. Journal Of The History Of The Behavioral Sciences, 52(2), 146-166.

- ^ Hubbard, K., & Hegarty, P. (2016). Blots and All: A History of the Rorschach Ink Blot Test in Britain. Journal Of The History Of The Behavioral Sciences, 52(2), 146-166.

- ^ Howard, J. W. (1953). THE HOWARD INK BLOT TEST. Journal Of Clinical Psychology, 9(3), 209-254

- ^ Howard, J. W. (1953). THE HOWARD INK BLOT TEST. Journal Of Clinical Psychology, 9(3), 209-254.

- ^ Rorschach test

- ^ Lilienfeld, S. O., Wood, J. M., & Garb, H. N. (2000). The scientific status of projective techniques. Psychological science in the public interest, 1(2), 27-66.

- ^ Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/ethics/code/index.aspx#9_11

- ^ J., Larsen, Randy (2010). Personality psychology : domains of knowledge about human nature. Buss, David M. (4th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Higher Education. ISBN 9780073370682. OCLC 436262737.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wood, J. M., & Lilienfeld, S. O. (1999). The Rorschach Inkblot Test: a case of overstatement?. Assessment, 6(4), 341-351.

- ^ Projective tests

- ^ Projective Test

- ^ Eichler, R. (1951). A comparison of the Rorschach and Behn-Rorschach inkblot tests. Journal Of Consulting Psychology, 15(3), 185-189. doi:10.1037/h0062446

- ^ Piotrowski, C. (2018). The Rorschach in Research on Neurocognitive Dysfunction: An Historical Overview, 1936-2016.SIS Journal Of Projective Psychology & Mental Health, 25(1), 44-53.

- ^ Kumar, R. (2010). Rorschach Ink Blot Test: A Guide to Modified Scoring System. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Rakesh_Kumar129/publication/304781749_Rorschach_Inkblot_Test_A_Guide_to_Modified_Scoring_System/links/577a788a08aec3b743356ec1/Rorschach-Inkblot-Test-A-Guide-to-Modified-Scoring-System.pdf