Reforms of the Ulysses S. Grant administration

Reforms of the Ulysses S. Grant administration | |

|---|---|

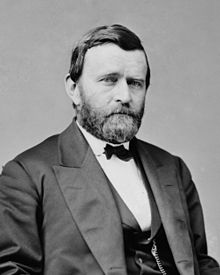

President Grant Circa 1870 | |

| 18th President of the United States | |

| In office March 4, 1869 – March 4, 1877 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Hiram Ulysses Grant April 27, 1822 Point Pleasant, Ohio, U.S. |

| Died | July 23, 1885 (aged 63) Wilton, New York, U.S. |

| Resting place | General Grant National Memorial Manhattan, New York |

| Political party | Republican |

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Personal 18th President of the United States Presidential campaigns

|

||

During Ulysses S. Grant's two terms as President of the United States (1869–1877) there were several executive branch investigations, prosecutions, and reforms carried-out by President Grant, Congress, and several members of his Cabinet, in the wake of several revelation of fraudulent activities within the administration. Grant's cabinet fluctuated between talented individuals or reformers and those involved with political patronage or party corruption. Some notable reforming cabinet members were persons who had outstanding abilities and made many positive contributions to the administration. These reformers resisted the Republican Party's demands for patronage to select efficient civil servants.

It was with the encouragement of these reformers that Grant established the first Civil Service Commission, and ended the moiety system. Many in his cabinet including his Secretary of State Hamilton Fish and his Secretary of Interior Jacob D. Cox implemented Civil Service reform in their respected departments. Historian H.W. Brands has noted that the Grant Administration thwarted the 1869 Gold Ring in addition to the successful prosecution the Whiskey Ring in 1876. The Grant administration took place during Reconstruction and a boom and bust economy following the Civil War that fueled financial corruption in Government offices. Several of Grant's cabinet members supported and implemented Civil Service reform in their respected federal departments. President Grant signed a bill into law that allowed the Postal Department to prosecute pornography through the mail, a law that is still in effect today. Grant appointed several leading reformers including Hamilton Fish, Benjamin Bristow, and Edwards Pierrepont. During his first administration Grant prosecuted and shut down the Ku Klux Klan under the Enforcement Acts he signed into law in 1870 and 1871. Grant, a trained military leader, was often at odds with Cabinet reformers who he believed were insubordinate to his administration. On several occasions Grant dismissed cabinet reformers without notice or explanation.

Reforming cabinet members

U.S. Secretary of State

(1869–1877)

Grant's cabinet fluctuated between talented individuals or reformers and those involved with political patronage or party corruption. Some notable reforming cabinet members were persons who had outstanding abilities and made many positive contributions to the administration. These reformers resisted the GOP demands for patronage to select efficient civil servants.[1][2] Grant's most successful appointment, Hamilton Fish, after the confirmation on March 17, 1869, went immediately to work and collected, classified, indexed, and bound seven hundred volumes of correspondence. He established a new indexing system that simplified retrieving information by clerks. Fish also created a rule that applicants for consulate had to take an official written examination to receive an appointment; previously, applicants were given positions on a patronage system solely on the recommendations of Congressmen and Senators. This raised the tone and efficiency of the consular service, and if a Congressman or Senator objected, Fish could show them that the applicant did not pass the written test.[3] According to Fish's biographer and historian Amos Elwood Corning in 1919, Fish was known as "a gentleman of wide experience, in whom the capacities of the organizer were happily united with a well-balanced judgment and broad culture".

Secretary of Treasury

(1869–1873)

Another reforming cabinet member was United States Secretary of Treasury George S. Boutwell who was confirmed by the Senate on March 12, 1869. His first actions were to dismiss S.M. Clark, the chief of U.S. Bureau and Engraving, and to set up a system of securing the plates that the paper money was printed on to prevent counterfeiting. Boutwell set up a system to monitor the manufacturing of money to ensure nothing would be stolen. Boutwell prevented collusion in the printing of money by preparing sets of plates for a single printing, with the red seal being imprinted in the Treasury Bureau. Boutwell persuaded Grant to have the Commissioner of Internal Revenue Alfred Pleasanton removed for misconduct over approving a $60,000 tax refund. In addition to these measures, Boutwell established a uniform mode of accounting at custom houses and ports. Boutwell along with Attorney General, Amos T. Akerman, were two of Grant's strongest cabinet members who advocated racial justice for African Americans.[4][5]

During Amos T. Akerman's tenure as Attorney General of the United States from 1870 to 1871, thousands of indictments were brought against Klansmen to enforce the Civil Rights Acts of 1866 and the Force Acts of 1870 and 1871. Born in the North, Akerman moved to Georgia after college and owned slaves; he fought for the Confederacy and became a Scalawag during Reconstruction, speaking out for blacks' civil rights. As U.S. Attorney General, he became the first ex-Confederate to reach the cabinet. Akerman was unafraid of the Klan and committed to protecting the lives and civil rights of blacks. To bolster Akerman's investigation, Grant sent in Secret Service agents from the Justice Department to infiltrate the Klan and to gather evidence for prosecution. The investigations revealed that many whites participated in Klan activities. With this evidence, Grant issued a Presidential proclamation to disarm and remove the Klan's notorious white robe and hood disguises. When the Klan ignored the proclamation, Grant sent Federal troops to nine South Carolina counties to put down the violent activities of the Klan. Grant teamed Akerman up with another reformer in 1870 – the first Solicitor General and native Kentuckian Benjamin Bristow – and the duo went on to prosecute thousands of Klan members and brought a brief quiet period of two years in the turbulent Reconstruction era.[6]

As perhaps Grant's most popular cabinet reformer, Benjamin H. Bristow was appointed Secretary of Treasury in June 1874. Bristow had served ably as Solicitor General of the United States from 1870 to 1872, prosecuting many Ku Klux Klan's men who violated African American voting rights. When Bristow assumed office he immediately made an aggressive attack on corruption in the department. Bristow discovered that the Treasury was not receiving the full amount of tax revenue from whiskey distillers and manufacturers from several Western cities, primarily St. Louis, Missouri. Bristow discovered in 1874 that the Government alone was being defrauded by $1.2 million. On May 13, 1875, armed with enough information, Bristow struck hard at the ring, seized the distilleries, and made hundreds of arrests; the Whiskey Ring ceased to exist. Although Grant and Bristow were not on friendly terms, Bristow sincerely desired to save Grant's reputation from scandal.[7] At the end of the Whiskey Ring prosecutions in 1876, there were 230 indictments, 110 convictions, and $3 million in tax revenues returned to the Treasury Department.[8][9]

In 1875, Grant paired up Secretary of Treasury Benjamin Bristow with U.S. Attorney General Edwards Pierrepont, a Yale graduate. The appointment was popularly accepted by the public as Bristow and Pierrepont successfully prosecuted members of the Whiskey Ring. Before becoming U.S. Attorney General, Pierrepont was part of a reforming group known as the "Committee of Seventy" and was successful at shutting down William M. Tweed's corrupt contracting Ring while he was a New York U.S. Attorney in 1870. Although Grant's reputation was vastly improved, Pierrepont had shown indifference in 1875 to the plight of freedmen by circumventing Federal intervention when White racists terrorized Mississippi's African American citizens over a fraudulent Democratic election. Every cabinet appointment made by Grant came with a political cost.[10]

Secretary of Interior

(1875–1877)

When Grant was in a bind to find a replacement for Secretary of War William W. Belknap, who abruptly resigned in 1876 amidst scandal, he turned to his good friend Alphonso Taft from Cincinnati. Taft, who accepted, served ably as Secretary of War until being transferred to the Attorney General position. As Secretary of War, Taft reduced military expenditures and made it so that no post-traderships would be given to any person except on the recommendation of the officers at the post. Grant then appointed Taft as U.S. Attorney General. Taft was a wise scholar and jurist educated at Yale University, and the Attorney General position suited him the best. During the controversial Presidential Election of 1876 between Rutherford B. Hayes and Samuel J. Tilden, Attorney General Taft and House Representative J. Proctor Knott had many meetings to decide the outcome of the controversial election. The result of the Taft-Knott negotiations, the Electoral Commission Act was passed by Congress and signed into law by Grant on January 29, 1877; it created a 15-member bipartisan committee to elect the next President. Hayes won the Presidency by one electoral vote two days before the March 4, 1877 Inauguration. Alphonso Taft was the father of future president William H. Taft.[11]

In 1875, the U.S. Department of the Interior was in serious disrepair with corruption and incompetence. The result was that United States Secretary of Interior Columbus Delano, reportedly having taken bribes to secure fraudulent land grants, was forced to resign from office on October 15, 1875.[12] On October 19, 1875, in a personal effort of reform, Grant appointed Zachariah Chandler to the position and was confirmed by the Senate in December 1875. Chandler immediately went to work on reforming the Interior Department by dismissing all the important clerks in the Patent Office. Chandler had discovered that fictitious clerks were earning money and that other clerks were earning money without performing services. Chandler simplified the patent application procedure and as a result reduced costs. Chandler, under Grant's orders, fired all corrupt clerks at the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Chandler also banned the practice of Native American agents, known as "Indian Attorneys" who were being paid $8.00 a day plus expenses for supposedly representing their tribes in Washington.[3]

Postmaster General John A. J. Creswell proved to be one of the ablest organizers ever to head the Post Office. He cut costs while greatly expanding the number of mail routes, postal clerks and letter carriers. He introduced the penny post card and worked with Fish to revise postal treaties. A Radical, he used the vast patronage of the post office to support Grant's coalition. He asked for the total abolition of the franking privilege since it reduced the revenue receipts by five percent. The franking privilege allowed members of Congress to send mail at the government's expense.[13]

Grant appointment, U.S. Postmaster Marshall Jewell, often called meetings with his clerks giving them new instructions on reform. Jewell was noted to have said to his clerks, "We are cleaning up the department by degrees, and we are getting it found on business principles."[14] Postmaster Jewell aided and stood by Secretary of the Treasury Benjamin H. Bristow shut down and prosecute the notorious Whiskey Ring; a tax evasion scheme by whiskey distillers that depleted the U.S. Treasury millions of dollars.[15] [16]

Grant's appointments of Bristow, Pierrepont, and Jewell on his cabinet, temporarily appeased reformers.[17]

Thwarted gold ring (1869)

In September 1869, financial manipulators Jay Gould and Jim Fisk set up an elaborate scam to corner the gold market through buying up all the gold at the same time to drive up the price and actively encouraging gold investment by speculators. The plan was to keep the government from selling gold, thus driving its price, while Gould promoted that a higher price of gold would help farmers gain more profits overseas on a good year of crops. President Grant's Secretary of Treasury George S. Boutwell had implemented a policy of monthly sales of Treasury gold to reduce and pay off the national debt, caused by the Civil War. This federal Treasury policy effectively kept the market price of gold low. Desiring the government to stay out of the gold business, President Grant stopped Boutwell's monthly sale of Treasury gold in September. Keeping track of the rapid rising price of gold at Gould's banking house in New York, President Grant and Secretary of Treasury George S. Boutwell ordered the sale of $4 million in gold on (Black) Friday, September 23. The release of the gold thwarted Gould's and Fisk's plan to corner the gold market. After the treasury gold was released, the market price of gold dropped. The effects of releasing the gold, however, had temporary detrimental effects on the economy as stock prices plunged and food prices dropped, devastating New York bankers and southern farmers for months.[18]

Enforcement Acts (1870–1871)

During his first administration, President Grant signed a series of laws known as the Enforcement Acts that were to reform the South and protect African Americans from violent attacks and intimidation by the Ku Klux Klan and Redeemers .[19] This was done in order to enforce the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the constitution that respectively gave African Americans United States citizenship and the right to vote. [19] The first bill that Grant signed into law was the Enforcement Act of 1870 on May 31, 1870. This law was designed to keep the Redeemers from attacking or threatening African Americans and white Republicans who supported Reconstruction. This act placed severe penalties on persons who used intimidation, bribery, or physical assault to prevent citizens from voting and placed elections under Federal jurisdiction.[20] In 1871 Congress passed the First Enforcement Act and Second Enforcement Act to specifically go after local units of the Ku Klux Klan after a Congressional investigation into the South instigated by President Grant revealed violence and intimidation against African Americans. President Grant signed the bill into law on April 20, 1871 after being convinced by Secretary of Treasury, George Boutwell, that federal protection was warranted, having cited documented atrocities against the Freedmen.[21] This law allowed the President to suspend habeas corpus on "armed combinations" and conspiracies by the Klan. The Act also empowered the president "to arrest and break up disguised night marauders". The actions of the Klan were defined as high crimes and acts of rebellion against the United States.[22][23]

The Ku Klux Klan in South Carolina was strongly entrenched and continued acts of violence against African American citizens. On October 12, 1871 President Grant, who was fed up with their violent tactics, ordered the Ku Klux Klan to disperse from South Carolina and lay down their arms under the authority of the Enforcement Acts. There was no response, and so on October 17, 1871, Grant issued a suspension of habeas corpus in all the 9 counties in South Carolina. Grant ordered federal troops in the state who then captured the Klan; who were vigorously prosecuted by Att. Gen. Akerman and Sol. Gen. Bristow. Although the Ku Klux Klan was effectively destroyed by 1873, Southern resistance against African Americans persisted and a system known has Jim Crow eventually dominated the entire South.[19] Other white supremacist groups emerged including the White League and the Red Shirts.[20]

Civil service commission (1871)

President Grant was the first U.S. President to recommend a professional civil service, successfully pass the initial legislation through Congress in 1871, and appointed the members for the first United States Civil Service Commission. The temporary Commission recommended administering competitive exams and issuing regulations on the hiring and promotion of government employees. Grant ordered their recommendations in effect in 1872; having lasted for two years until December, 1874. Many of Grant's cabinet implemented the Commission's reform rules that improved the overall moral and merit of the federal workforce. At the New York Custom House, a port that took in hundreds of millions of dollars a year in revenue, persons who applied for an entry position had to take and pass a civil service examination. Chester A. Arthur who was appointed by Grant as New York Custom Collector stated that the examinations excluded and deterred unfit persons from getting employment positions.[24] Grant, however, allowed Secretary Delano to exempt the Department of Interior from the Commission's rulings. However, Congress, in no mood to reform itself, denied any long-term reform by refusing to enact the necessary legislation to make the changes permanent. Historians have traditionally been divided whether patronage, meaning appointments made without a merit system, should be labelled corruption.[25]

The movement for Civil Service reform reflected two distinct objectives: to eliminate the corruption and inefficiencies in a non-professional bureaucracy, and to check the power of President Johnson. Although many reformers after the Election of 1868 looked to Grant to ram Civil Service legislation through Congress, he refused, saying: "Civil Service Reform rests entirely with Congress. If members will give up claiming patronage, that will be a step gained. But there is an immense amount of human nature in the members of Congress, and it is human nature to seek power and use it to help friends. You cannot call it corruption – it is a condition of our representative form of Government."[26] Grant used patronage to build his party and help his friends. He instinctively protected those who he thought were the victims of injustice or attacks by his enemies, even if they were guilty.[27] Grant believed in loyalty with his friends, as one writer called it the "Chivalry of Friendship".[28]

Anti Obscenity Act (1873)

On March 3, 1873, President Grant signed into law the Comstock Act which made it a federal crime to mail articles "for any indecent or immoral use". Strong anti-obscenity moralists, led by the YMCA's Anthony Comstock, easily secured passage of the bill. Grant signed the bill after he was assured that Comstock would personally enforce it. Comstock went on to become a special agent of the Post Office appointed by Secretary James Cresswell. Comstock prosecuted pornographers, imprisoned abortionists, banned nude art, stopped the mailing of information about contraception, and tried to ban what he considered bad books.[29] The law banned obscene material from entering into the United States from foreign countries through the U.S. Postal System.[30] Obscene materials were allowed to be immediately seized and destroyed by federal authority.[31]

Treasury Department (1874)

On June 3, 1874 President Grant appointed Benjamin Bristow Secretary of the Treasury after William A. Richardson was removed in light of the Sanborn incident.[32] As Treasury Secretary, Bristow proved to be an energetic and popular and trusted reformer among reformers, even gaining the admiration of one President Grant's staunch critics, Senator Carl Schurz. He initiated a much-needed internal reorganization of the Treasury Department, dismissing the Second-Comptroller for inefficiency, shaking up the detective force, and consolidating collection districts in the Customs and Internal Revenue Services.

Justice Department (1875)

When Edwards Pierrepont assumed the office of U.S. Attorney General, appointed by President Grant, he immediately implemented overdue reform in the South's U.S. Marshal and U.S. Attorney departments.[33] The culmination of these reforms took place in June, 1875. Attorney General Pierrepont had given specific reform orders to U.S. Attorneys and U.S. Marshals in the South that were vigorously enforced.[33] Pierrepont ran extensive investigations into the conduct of the U.S. Attorneys and U.S. Marshals, exposing fraud and corruption. Pierrepont was fully sustained by President Grant's endorsement of the investigations, reforms, and persons to be removed and replaced from office.[33]

Interior Department (1875)

On October 15, 1875 President Grant's appointed Secretary of Interior Columbus Delano resigned due to scandal. Rampant corruption prevailed in the Interior Department's Patent Office and the Department of Indian Affairs due to Delano's lax supervision. On October 19, 1875 Grant appointed Republican party leader and reformer Zachariah Chandler Secretary of the Interior. Chandler, obtaining Grant's approval, immediately went to work reforming the Interior Department by dismissing all the important clerks in the Patent Office. Chandler had discovered that during Delano's tenure, money had been paid to fictitious clerks while other clerks had been paid without performing any services. Chandler next turned to the Department of Indian Affairs to reform another Delano debacle. President Grant ordered Chandler to fire everyone, saying, "Have those men dismissed by 3 o'clock this afternoon or shut down the bureau." Chandler did exactly as Grant had ordered, and banned bogus agents, known as "Indian Attorneys," who had been paid $8.00 a day plus expenses for, ostensibly, providing tribes with representation in the nation's capital. Many of these agents were unqualified and swindled the Native American tribes into believing they had a voice in Washington.[34]

Prosecuted Whiskey Ring (1875–1876)

After the American Civil War, whiskey distillers in St. Louis developed a tax evasion ring that depleted the U.S. Treasury. By 1875, the Whiskey Ring had grown into a nationwide criminal syndicate that included whiskey distillers, brokers, and government officials; making enormous profits from the sale of untaxed whiskey. Also rumored, was that in 1872 the Ring had secretly funded the Republican Presidential campaign. In an effort of reform and to clean up corruption, President Ulysses S. Grant appointed Benjamin Bristow, as U.S. Secretary of Treasury in 1874, who immediately discovered millions of dollars were being depleted from the U.S. Treasury.[35] Under orders from President Grant, in May 1875, Sec. Bristow struck hard at the Ring, nationally shutting down distilleries, arresting hundreds involved in the ring having obtained over 350 indictments. The Ring through Bristow's vigorous raids had been effectively shut down. In April 1875, President Grant appointed Pierrepont Attorney General and teamed him up with Bristow to prosecute the Ring and clean up corruption.[36]

During the Summer of 1875, both Bristow and Pierrepont obtained President Grant's order to "let know guilty man escape." During the Fall of 1875, evidence was discovered that Grant's private secretary, Orville Babcock had been involved in the Ring. Bristow and Pierrepont, stayed behind after a cabinet meeting with President Grant and showed him correspondence between Babcock and William Joyce in St. Louis, indicted in the Ring, cryptic telegram messages as evidence of Babcock's involvement in the Ring. Babcock was summoned to the Oval Office for an explanation and was told to send a telegram to bring Wilson to Washington D.C. After Babcock did not return to the Oval Office, Pierrepont discovered Babcock was in the process of writing a letter warning Wilson to be on his guard. This angered Attorney General Pierrepont, who spilled ink over Babcock's letter and shouted, "You don't want to send your argument; send the fact, and go there and make your explanation. I do not understand it."[37] Babcock was indicted and later acquitted in a trial in St. Louis, after an oral deposition from President Grant defending Babcock was given to the jury. The Justice Department obtained 110 convictions of persons involved in the Whiskey Ring.

Proposed reforms

Grant suggested other reforms as well, including a proposal that states should offer free public schooling to all children; he also endorsed the Blaine Amendment, which would have forbidden government aid to schools with religious affiliations.[38]

Dismissed or resigned Cabinet reformers

Three of Grant's reform Cabinet members were forced to resign or dismissed by Grant without notice or explanation including Ebenezer R. Hoar, Amos T. Akerman, and Marshall Jewell.[39][14] Attorney General Hoar was dismissed for political and geographic reasons. Politically Grant wanted to implement a tougher Reconstruction Policy on the South where there was violence against African Americans by the Ku Klux Klan. Hoar believed in a state prosecution of the Klan rather than federal. Hoar was also replaced since Grant had appointed two men from Massachusetts on his Cabinet, including Hoar and Secretary of Treasury George S. Boutwell. In 1870, Grant sent a letter to Hoar demanding his resignation without any explanation or warning. Grant replaced Hoar with reformer Akerman who went onto prosecute the Ku Klux Klan.

Akerman was later forced to resign by Grant without notice or explanation and replaced by George H. Williams. Grant was under pressure to replace Akerman for political reasons due to his zealous prosecution of the Klan and his reluctance to appease the railroad lobby. Grant did not want the image of being a Presidential dictator. Williams continued to prosecute the Klan until June 1873, the Justice Department was understaffed and underfunded. Grant's Secretary of Interior Jacob D. Cox resigned due to lack of cooperation from Republican Party leaders after implementing Civil Service reform in the Department of Interior. Cox was also under pressure to resign from Grant who believed Cox was overstepping Grant's authority as President. Both Cox and Hoar opposed Grant's Santo Domingo annexation plan. Cox, who afterwards joined the Liberal Republicans, was replaced by Columbus Delano who discontinued Cox's civil service policy that resulted in creating a spoils system within the Department of Interior, until Delano's resignation and replacement by Zachariah Chandler who reformed the department.

Postmaster Jewell was ubruptly dismissed without notice or explanation after a Cabinet meeting because Grant believed Jewell and Secretary of Treasury Benjamin Bristow were both disloyal to the administration. Both Bristow and Jewell ran for the presidency in 1876. During this time period Presidents could run for office indefinitely. Bristow, who successfully prosecuted and shut down the Whiskey Ring in 1875, was not out right dismissed by Grant. Rather, Bristow resigned on his own under pressure from Grant in 1876, since Bristow had discovered Grant's private secretary Orville Babcock was involved in the Whiskey Ring corruption.

See also

References

- ^ Nevins 1957, p. 367.

- ^ Smith 2001, pp. 468–73.

- ^ a b Corning 1918, pp. 49–54.

- ^ Boutwell 2008, pp. 120–123.

- ^ McFeely 2002, p. 369.

- ^ Trelease 1995.

- ^ Rives 2000.

- ^ PoliticalCorruption.net

- ^ Rhodes 1912, pp. 182–185.

- ^ Smith 2001, p. 585.

- ^ Leonard 1920.

- ^ Salinger 2005, pp. 374–375.

- ^ Nevins 1957, p. 139.

- ^ a b Chicago Daily Tribune (Feb 18, 1883), Marshall Jewell

- ^ New England Historic Genealogical Society, p. 127

- ^ Moody 1933, p. 64.

- ^ Chernow 2017, p. 787.

- ^ Smith 2001, pp. 481–490.

- ^ a b c Simpson 2005, p. Introduction and Acknolledgements xxiii.

- ^ a b Scaturro 2006.

- ^ (1990), Grant Memoirs and Selected Letters pp. 1146, 1147; McFeely (2002), Grant: A Biography, pp. 368–369

- ^ Trelease 1971, ch. 22–25.

- ^ McFeely (2002), Grant: A Biography, pp. 368–369

- ^ Howe (1935), p. 48, 295

- ^ Smith 2001, pp. 587–589.

- ^ Young 1880, p. 126.

- ^ Nevins 1957, p. 710.

- ^ Smith 2001 pp. 587–589.

- ^ Carpenter 2001, pp. 84–85.

- ^ Statutes at Large, 42nd Congress, 3rd Session, p. 599

- ^ Statutes at Large, 42nd Congress, 3rd Session, p. 600

- ^ Memormorial of Benjamin Helm Bristow (1897), p.10

- ^ a b c New York Times (June 17, 1875), The Conduct of Southern Marshals and Attorneys

- ^ Pierson 1880, pp.343–345

- ^ Smith (1981), Grant, p. 584

- ^ Smith (2001), Grant, p. 585

- ^ McFeely (1981), Grant A Biography, p. 411

- ^ Crapol 2000, p. 42.

- ^ McFeely, p. 365

Sources

- Boutwell, George S. (2008) [First published 1902]. Reminiscences of Sixty Years in Public Affairs. New York City: Greenwood Press. pp. 131–133. OCLC 1857.

- Carpenter, Daniel P. (2001). "Chapter Three". The Forging of Bureaucratic Autonomy: Reputations, Networks, and Policy Innovation in Executive Agencies, 1862–1928. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. pp. 84–85. ISBN 978-0-691-07009-4. OCLC 47120319. Retrieved April 1, 2010.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Corning, Amos Elwood (1918). Hamilton Fish. New York City: Lamere Publishing Company. pp. 49–54. OCLC 2959737.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Howe, George Frederick (1935). Chester A. Arthur A Quarter-Century of Machine Politics. New York, New York: Frederick Unger Publishing Co.

- Leonard, Lewis Alexander (1920). Life of Alphonso Taft. New York City: Hawke Publishing Company. OCLC 60738535. Retrieved January 28, 2010.

Life of Alphonso Taft.

- McFeely, William S. (1981). Grant: A Biography. Norton. ISBN 0-393-01372-3.

- McFeely, William S. (2002) [First published 1981]. Grant: A Biography. New York City: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-01372-6. OCLC 6889578.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help), Pulitzer prize, but hostile to Grant

- Moody, Robert E. (1933). Dumas Malone (ed.). Dictionary of American Biography Jewell, Marshall. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- Nevins, Allan (1937). Hamilton Fish: The Inner History of the Grant Administration. New York City: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-8044-1676-4. OCLC 478495. Retrieved April 11, 2010.(subscription required)

- Pierson, Arthur Tappen (1880). "Zachariah Chandler: An Outline Sketch of his Life and Public Services". Detroit Post and Tribune. pp. 343–345. OCLC 300744189.

- Rhodes, James Ford (1906). History of the United States from the Compromise of 1850 to the Final Restoration of Home Rule at the South in 1877: v. 7, 1872–1877. New York: Macmillan. OCLC 3214496. Retrieved January 30, 2010.

- Rhodes, James G. (1906). History of the United States from the Compromise of 1850 to the McKinley-Bryan Campaign of 1896: vol. 6: 1866–1872. OCLC 765948.

- Rives, Timothy (Fall 2000). "Grant, Babcock, and the Whiskey Ring". Prologue. 32 (3). Retrieved January 18, 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Simpson, Brooks; Kelsey, Marie Ellen (2005). Ulysses S. Grant: A Bibliography. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger Publishers. ISBN 0-313-28176-9.

- Smith, Jean Edward (2001). Grant. New York City: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-684-84926-3. OCLC 45387618.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|lay-url=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laydate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysource=ignored (help)

- Salinger, Lawrence M. (2005). Encyclopedia of White-collar & Corporate Crime, Volume 2. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications. pp. 374–375. ISBN 978-0-7619-3004-4. Retrieved January 30, 2010.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Scaturro, Frank (October 26, 2006). "The Presidency of Ulysses S. Grant, 1869–1877". College of St. Scholastica. Archived from the original on July 19, 2011. Retrieved January 30, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Trelease, Allen W. (April 1995) [1971]. White Terror: The Ku Klux Klan Conspiracy and Southern Reconstruction. Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 978-0-06-131731-6. OCLC 4194613.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)