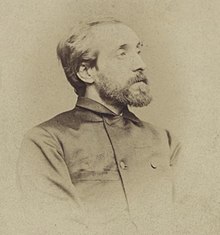

Hugh Owen Thomas

Hugh Owen Thomas (23 August 1834 – 06 January 1891) was a Welsh surgeon. He is considered the father of orthopaedic surgery in Britain.

Early life

Hugh Owen Thomas descended from a young boy who had been shipwrecked in Anglesey in 1745. Given the name Evan Thomas by the family that adopted and raised him, he established a family tradition of bone-setting. Evan Thomas — the grandson of the original survivor, and Hugh’s father — had moved to Liverpool at the age of 19, where he set up a successful practice as bone-setter. Evan, however, was not a trained physician, and three times he was taken to court to defend his practice. Although he was never convicted, the constant jealousy and antagonism of the medical community was a great toll on him; at one point his cottage was even burned down. As a result of this, he decided to send all his five sons to train and qualify as doctors.

Professional career

Hugh trained with his uncle, Owen Roberts at St. Asaph in North Wales for four years, then he studied medicine at Edinburgh and University College, London. He qualified as MRCS in 1857. Returning to Liverpool, he first worked with his father, but incompatible temperaments did not allow this for long, so in 1859 he set up his own practice in the poorer part of town.

Hugh was known as an eccentric and rather temperamental man. A rumour had it that he would attack victims himself, and break their bones, in order to have patients on which to practice.[1] He was short; just over five feet tall, always wore a black coat buttoned all the way up, a patch over one eye, and constantly had a cigarette in his mouth. Among the poor people of Liverpool though, he stood in great esteem. He practiced from his home in No. 11, Nelson Street, where he worked all day from five or six in the morning, and every Sunday he would treat patients for free.

Medical legacy

His contribution to British orthopaedics was manifold. In the treatment of fractures and tuberculosis he advocated rest, which should be 'enforced, uninterrupted and prolonged'. In order to achieve this he created the so-called 'Thomas Splint', which would stabilise a fractured femur and prevent infection. He is also responsible for numerous other medical innovations that all carry his name: 'Thomas's collar' to treat tuberculosis of the cervical spine, 'Thomas's manoeuvre', an orthopaedic investigation for fracture of the hip joint, Thomas test, a method of detecting hip deformity by having the patient lying flat in bed, 'Thomas's wrench' for reducing fractures,[2] as well as an osteoclast to break and reset bones. The 'Thomas heel' is part of a shoe for children consisting of a heel one-half inch (12 mm) longer, and an eighth to a sixth of an inch (4 to 6 mm) higher on the inside. This is used to bring the heel of the foot into varus deformity, and to prevent depression in the region of the head of the ankle bone.[3]

His work was never fully appreciated in his own lifetime, but when his nephew, Sir Robert Jones, applied his splint during the First World War, this reduced mortality of compound fractures of the femur from 87% to less than 8% in the period from 1916 to 1918.

Works

- Diseases of the hip, knee and ankle joints (1876)

- A review of the past and present treatment of disease in the hip, knee, and ankle joints: With their deformities (1878)

- The past and present treatment of intestinal obstructions (1879)

- The treatment of fractures of the lower jaw (1881)

- Intestinal disease and obstruction (1883)

- Nerve inhibition and its relation to the practice of medicine (1883)

- Principles of the treatment of diseased joints (1883)

- The collegian of 1666 and the collegians of 1885: Or, what is recognised treatment? (1885)

- The principles of the treatment of fractures and dislocations (1886)

- Fractures, dislocations, diseases and deformities of the bones of the trunk and upper extremities (1887)

- A new lithotomy operation (1888)

- An argument with the censor at St. Luke's Hospital, New York (1889)

- Fractures, dislocations, deformities and diseases of the lower extremities (1890)

- Lithotomy (1890)

References

- ^ Williams, Peter Howell (1971). Liverpolitana: a miscellany of People and Places. Liverpool. p. 47.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Thomas wrench for club foot". Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow. Archived from the original on 19 November 2014. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- ^ http://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/Thomas+heel

Further reading

- Aitken, D. McCrae, Hugh Owen Thomas: His Principles and Practice (London, Oxford university press, 1935)

- Watson, Frederick, Hugh Owen Thomas: A Personal Study (London, Oxford university press, 1934)

- Le Vay, Abraham David, The life of Hugh Owen Thomas (Edinburgh, 1956)

- McMurray, Thomas Porter, The life of Hugh Owen Thomas: Centenary Lecture Delivered at the Liverpool Medical Institution (1935)

- Galasko, Charles S. B. (1988). "Sir Harry Platt and the evolution of orthopaedic surgery in North-West England". In Galasko, Charles Samuel Bernard; Noble, Jonathan (eds.). Current Trends in Orthopaedic Surgery. Manchester University Press. ISBN 9780719025358.

External links

- Hugh Owen Thomas History of Surgeons – surgeons.org.uk

- Biography at Surgical Tutor

- Biography at Who Named It?