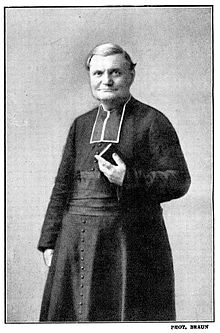

Ernest Jouin

Ernest Jouin | |

|---|---|

Ernest Jouin (1844–1932) | |

| Born | 21 December 1844 Angers, France |

| Died | 27 June 1932 Paris, France |

| Nationality | French |

| Occupation(s) | Priest Essayist Journalist |

Monsignor Ernest Jouin (21 December 1844 – 27 June 1932) was a French Catholic priest and essayist, known for his promotion of the Judeo-Masonic conspiracy theory. He also published the first French edition of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion.[1]

Life

Jouin was born in 1844 in Angers in a family of Catholic artisans. His father died when he was four, and he was sent to a novitiate of the Dominican Order to be educated. From there, he moved to the seminary of Angers and was ordained as a priest in 1868.[2] From Angers, he moved to Paris in 1875, where he served as a parish priest until the end of his life.[3] He strongly criticized the anti-clerical measures introduced by the government of Émile Combes, and was sentenced in 1907 to a fine for his writings regarded as subversive.[3] He attributed the incident to Freemasonry and joined several anti-Masonic organizations before founding his own.[2]

In 1912, Jouin founded the Ligue Franc-Catholique. The league's journal, the Revue internationale des sociétés secrètes, was one of the two main anti-Semitic tribunes of the interwar period (along with the paper of the Action Française). Revue often published right-wing antisemitic canards from Russian, such as hoaxes about blood libel, and claims that Bolshevism was a Judeo-Masonic plot.[1] Describing the Protocols, Jouin wrote: "From the triple viewpoint of race, of nationality, and of religion, the Jew has become the enemy of humanity."[4] Pope Benedict XV made Jouin an Honorary Prelate.[5] Pope Pius XI praised Jouin for "combating our mortal [Jewish] enemy" and appointed him to high papal office as a protonotary apostolic.[1][4]

References

- ^ a b c Marks, Steven Gary (2003). How Russia Shaped the Modern World: From Art to Anti-semitism, Ballet to Bolshevism. Princeton University Press. p. 159.

- ^ a b James, Marie-France (1981). Esotérisme, occultisme, franc-maçonnerie et christianisme aux XIXe et XXe siècles : explorations bio-bibliographiques. Paris: Nouvelles Éditions Latines. p. 156-158. ISBN 978-2723301503.

- ^ a b Kreis, Emmanuel (2017). Quis Ut Deus?: Antijudeo-maconnisme Et Occultisme En France Sous La IIIe République. Paris: Les Belles Lettres. pp. 905–920 and passim. ISBN 978-2251447117.

- ^ a b Michael, R. (2008). A History of Catholic Antisemitism: The Dark Side of the Church. Springer. p. 171.

- ^ McElligott, Anthony (2017). Antisemitism Before and Since the Holocaust: Altered Contexts and Recent Perspectives. Springer. p. 92.

- 1844 births

- 1932 deaths

- Advocates of conspiracy theories involving Jews

- Anti-Masonry

- Antisemitism in France

- Far-right politics in France

- French anti-communists

- French essayists

- French journalists

- French male non-fiction writers

- French Roman Catholics

- Integralism

- Late modern Christian antisemitism

- Roman Catholic conspiracy theorists

- Roman Catholic writers

- European Roman Catholic clergy stubs

- French religious biography stubs