Kingdom of Arles

| Kingdom of Arles Regnum Arelatense (Latin) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kingdom of Holy Roman Empire (from 1032) | |||||||||||||

| 933–1378 | |||||||||||||

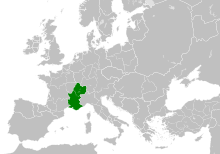

The Kingdom of Arles/Burgundy within Europe at the beginning of the 11th century | |||||||||||||

Burgundy in the 12–13th century: | |||||||||||||

| Capital | Arles | ||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||

• 1000[1] | 133,400 km2 (51,500 sq mi) | ||||||||||||

| • Type | Monarchy | ||||||||||||

| Historical era | High Middle Ages | ||||||||||||

| 933 | |||||||||||||

• Rudolph III pledged succession to King Henry II of Germany | May 1006 | ||||||||||||

• Rudolph III died without issue; kingdom inherited by Emperor Conrad II | 6 September 1032 | ||||||||||||

• Emperor Charles IV detached the County of Savoy | 1361 | ||||||||||||

| 1378 | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||

The Kingdom of Arles (also known as Arelat) was a dominion established in 933 by the merger of the kingdoms of Upper and Lower Burgundy under King Rudolf II. The kingdom came to be named after the Lower Burgundian residence at Arles. It is alternatively known as the "Kingdom of the Two Burgundies", or as the "Second Kingdom of Burgundy", in contrast to the Kingdom of the Burgundians of Late Antiquity.

Its territory stretched from the Mediterranean Sea to the High Rhine River in the north, roughly corresponding to the present-day French regions of Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur, Rhône-Alpes and Franche-Comté, as well as western Switzerland. It was ruled by independent kings of the Elder House of Welf until 1032, after which it was incorporated into the Holy Roman Empire.[2]

Carolingian Burgundy

Since the conquest of the First Burgundian kingdom by the Franks in 534, its territory had been ruled within the Frankish and Carolingian Empire. In 843, the three surviving sons of Emperor Louis the Pious, who had died in 840, signed the Treaty of Verdun which partitioned the Carolingian Empire between them: the former Burgundian kingdom became part of Middle Francia, which was allotted to Emperor Lothair I (Lotharii Regnum), with the exception of the later Duchy of Burgundy—the present-day Bourgogne—which went to Charles the Bald, king of West Francia. King Louis the German received East Francia, comprising the territory east of the Rhine River.

Shortly before his death in 855, Emperor Lothair I in turn divided his realm between his three sons in accordance with the Treaty of Prüm. His Burgundian heritage would pass to his younger son Charles of Provence (845–863). Then in 869 Lothair I's son, Lothair II, died without legitimate children, and in 870 his uncle Charles the Bald and Louis the German by the 870 Treaty of Meerssen partitioned his territory: Upper Burgundy, territory north of the Jura mountains (Bourgogne Transjurane), went to Louis the German, while the rest went to Charles the Bald. By 875 all sons of Lothair I had died without heirs and the other Burgundian territories were held by Charles the Bald.

In the confusion after the death of Charles' son Louis the Stammerer in 879, the West Frankish count Boso of Provence established the Kingdom of Lower Burgundy (Bourgogne Cisjurane) at Arles. In 888, upon the death of the Emperor Charles the Fat, son of Louis the German, Count Rudolph of Auxerre, Count of Burgundy, founded the Kingdom of Upper Burgundy at Saint-Maurice which included the County of Burgundy, in northwestern Upper Burgundy.

In 933, Hugh of Arles ceded Lower Burgundy to Rudolph II of Upper Burgundy in return for Rudolph relinquishing his claim to the Italian throne. Rudolph merged both Upper and Lower Burgundy to form the Kingdom of Arles (Arelat). In 937, Rudolph was succeeded by his son Conrad the Peaceful. Inheritance claims by Hugh of Arles were rejected, with the support of Emperor Otto I.

In 993, Conrad was succeeded by his son Rudolph III, who in 1006 was forced to sign a succession treaty in favor of the future Emperor Henry II. Rudolph attempted to renounce the treaty in 1016 without success.

Imperial Arelat

In 1032, Rudolph III died without any surviving heirs, and the kingdom passed in accordance with the 1006 treaty to Henry's successor, Emperor Conrad II from the Salian dynasty, and Arelat was incorporated in the Holy Roman Empire, though the kingdom operated with considerable autonomy.[2] Though from that time the emperors held the title "King of Arles", few went to be crowned in the cathedral of Arles. An exception was Frederick Barbarossa who was crowned King of Burgundy by the archbishop of Arles in 1178.

Between the 11th century and the end of the 14th century, several parts of Arelat's territory broke away: Provence, Vivarais, Lyonnais, Dauphiné, Savoy, the Free County of Burgundy, and parts of western Switzerland.[2] The Free County of Burgundy was acquired by the Imperial House of Hohenstaufen in 1190 and the eastern parts of Upper Burgundy fell to the House of Zähringen. Later, when the Zähringen line died out, these lands were inherited by the Habsburgs. Most of the territory of Lower Burgundy was progressively incorporated into France—the County of Provence fell to the Capetian House of Anjou in 1246 and finally to the French crown in 1481, the Dauphiné was annexed and sold to King Philip VI of France in 1349 by Dauphin Humbert II of Viennois. In 1361, Emperor Charles IV detached the County of Savoy from the Burgundian kingdom.

In 1365, Charles was the last emperor to be crowned king of Arles. In 1378, Charles appointed the Dauphin of France (later King Charles VI of France) as permanent Imperial vicar to administer nominally on behalf of the Empire what remained of Arelat, and from then on Arelat in effect ceased to exist. However, the title "King of Arles" remained one of the Holy Roman Emperor's subsidiary titles until the dissolution of the Empire in 1806, and the office of the Archbishop of Trier continued to act as an archchancellor and prince-elector for the King of the Romans (the designated future Holy Roman Emperor), a status that was confirmed by the Golden Bull of 1356.

Despite the title's permanent union with that of king of the Romans, the Arelat was considered for reconstitution as a separate state several times. The most serious occasion was under Pope Nicholas III and sponsored by Charles of Anjou. Between 1277 and 1279, Charles, at that time already king of Sicily, Rudolf of Habsburg, king of the Romans and aspirant to the Imperial crown, and Margaret of Provence, queen dowager of France, settled their dispute over the County of Provence, and also over Rudolf's bid to become the sole Imperial candidate. Rudolf agreed that his daughter Clemence of Austria would marry Charles's grandson Charles Martel of Anjou, with the whole Arelat as her dowry. In exchange, Charles would support the imperial crown being made hereditary in the House of Habsburg. Pope Nicholas expected Northern Italy to become a kingdom carved out of the Imperial territory and be given to his family, the Orsini. In 1282, Charles was ready to send the child couple to reclaim the old royal title of kings of Arles, but the War of the Sicilian Vespers frustrated his plans.[3]

See also

References

Literature

- Chiffoleau, Jacques (1994). "I ghibellini nel regno di Arles". In Pierre Toubert; Agostino Paravicini Bagliani (eds.). Federico II e le città italiane. Palermo. pp. 364–88.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Chiffoleau, Jacques (2005). "Arles, regno di". Federico II: enciclopedia fridericiana. Vol. Vol. 1. Rome: Istituto dell'Enciclopedia Italiana.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|volume=has extra text (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cope, Christopher (1987). Phoenix Frustrated: The Lost Kingdom of Burgundy. Constable.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cox, Eugene L. (1967). The Green Count of Savoy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cox, Eugene L. (1974). The Eagles of Savoy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cox, Eugene L. (1999). "The Kingdom of Burgundy, the Lands of the House of Savoy and Adjacent Territories". In David Abulafia (ed.). The New Cambridge Medieval History, Volume V: c. 1198–c. 1300. Cambridge University Press. pp. 358–74.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Davies, Norman (2011). Vanished Kingdoms: The History of Half-Forgotten Europe. Penguin.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Font-Réaulx, Jacques de (1939). "Les diplômes de Frédéric Barberousse relatifs au royaume d'Arles à propos d'un livre récent". Annales du Midi. 51 (203): 295–306.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fournier, Paul (1886). Le royaume d'Arles et de Vienne et ses relations avec l'empire: de la mort de Frédéric II à la mort de Rodolphe de Habsbourg, 1250–1291. Paris: Victor Palmé.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fournier, Paul (1891). Le royaume d'Arles et de Vienne (1138–1378): Étude sur la formation territoriale de la France dans l'Ést et le Sudest. Paris: Alphonse Picard.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fournier, Paul (1936). "The Kingdom of Burgundy or Arles from the Eleventh to the Fifteenth Century". In C. W. Previté-Orton; Z. N. Brooke (eds.). The Cambridge Medieval History, Volume VIII: The Close of the Middle Ages. Cambridge University Press. pp. 306–31.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Heckmann, Marie-Luise (2000). "Das Reichsvikariat des Dauphins im Arelat 1378: vier Diplome zur Westpolitik Kaiser Karls IV". In Ellen Widder; Mark Mersiowsky; Maria-Theresia Leuker (eds.). Manipulus florum: Festschrift für Peter Johanek zum 60. Geburtstag. Münster: Waxmann. pp. 63–97.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Jacob, Louis (1906). Le royaume de Bourgogne sous les empereurs franconiens (1038–1125): Essai sur la domination impériale dans l'est et le sud-est de la France aux XIme et XIIme siècles. Paris: Honoré Champion.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Poole, Reginald (1913). "Burgundian Notes, III: The Union of the Two Kingdoms of Burgundy". English Historical Review. 28 (109): 106–12.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Poupardin, René (1907). Le royaume de Bourgogne (888–1038): étude sur les origines du royaume d'Arles. Paris: Honoré Champion.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Previté-Orton, Charles William (1912). The Early History of the House of Savoy (1000–1233). Cambridge University Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Viard, Paul (1911). "La dîme ecclésiastique dans le royaume d'Arles et de Vienne aux XIIe et XIIIe siècles". Zeitschrift der Savigny-Stiftung für Rechtsgeschichte: Kanonistische Abteilung. 1 (1): 126–59.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wilson, Peter (2016). Heart of Europe: A History of the Holy Roman Empire. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- States and territories established in the 930s

- States and territories disestablished in 1378

- 11th century in the Holy Roman Empire

- Former monarchies of Europe

- Kingdom of Burgundy

- Arles

- 1378 disestablishments in Europe

- Medieval Switzerland

- 933 establishments

- 1030s establishments in the Holy Roman Empire

- 1032 establishments in Europe

- Monarchy of the Holy Roman Empire

- History of Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur

- History of Rhône-Alpes

- History of Franche-Comté

- 10th-century establishments in France