Joe Hewitt (RAAF officer)

Joseph Eric (Joe) Hewitt | |

|---|---|

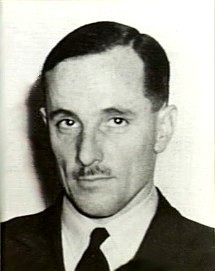

Air Commodore Joe Hewitt, 1942 | |

| Born | 13 April 1901 Tylden, Victoria |

| Died | 1 November 1985 (aged 84) Melbourne |

| Allegiance | Australia |

| Service | Royal Australian Navy Royal Australian Air Force |

| Years of service | 1915–1956 |

| Rank | Air Vice-Marshal |

| Commands | No. 101 Flight (1931–1933) No. 104 Squadron RAF (1936–1938) No. 9 Operational Group (1943) |

| Battles / wars | World War II |

| Awards | Commander of the Order of the British Empire |

| Other work | Businessman Author |

Air Vice-Marshal Joseph Eric Hewitt, CBE (13 April 1901 – 1 November 1985) was a senior commander in the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF). A Royal Australian Navy officer who transferred permanently to the Air Force in 1928, he commanded No. 101 (Fleet Cooperation) Flight in the early 1930s, and No. 104 (Bomber) Squadron RAF on exchange in Britain shortly before World War II. Hewitt was appointed the RAAF's Assistant Chief of the Air Staff in 1941. The following year he was posted to Allied Air Forces Headquarters, South West Pacific Area, as Director of Intelligence. In 1943, he took command of No. 9 Operational Group, the RAAF's main mobile strike force, but was controversially sacked by the Chief of the Air Staff, Air Vice Marshal George Jones, less than a year later over alleged morale and disciplinary issues.

Described as a "small, dapper man",[1] who was "outspoken, even 'cocky'",[2] Hewitt overcame the setback to his career during the war and made his most significant contributions afterwards, as Air Member for Personnel from 1945 to 1948. Directly responsible for the demobilisation of thousands of wartime staff and the consolidation of what was then the world's fourth largest air force into a much smaller peacetime service, he also helped modernise education and training within the RAAF. Hewitt was appointed a Commander of the Order of the British Empire in 1951, the same year he became Air Member for Supply and Equipment. Retiring from the military in 1956, he went into business and later managed his own publishing house. He wrote two books including Adversity in Success, a first-hand account of the South West Pacific air war, before his death in 1985 aged 84.

Early career

Born on 13 April 1901 in Tylden, Victoria, Joseph Eric Hewitt was the son of Joseph Henry Hewitt and his wife Rose Alice, née Harkness.[3][4] He attended Scotch College, Melbourne, before entering the Royal Australian Naval College at Jervis Bay in 1915, aged 13.[1] After graduating in 1918, Hewitt was posted to Britain as a midshipmen to serve with the Royal Navy.[3] He rose to lieutenant in the RAN before volunteering for secondment to the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) as a flight lieutenant in January 1923.[1][5] Hewitt undertook the pilots' course at No. 1 Flying Training School, Point Cook, and graduated at the end of the year.[6] He was further seconded to the Royal Air Force in May 1925,[7] holding a temporary commission as a flying officer until September.[8] He married Lorna Bishop in Sydney on 10 November; they had three daughters.[3]

In August 1926, Hewitt joined the newly formed No. 101 (Fleet Cooperation) Flight, operating Seagull III amphibians. Prior to the unit deploying to Queensland to survey the Great Barrier Reef with HMAS Moresby, he practiced manoeuvres around the centre of Melbourne, landing in the Yarra River near Flinders Street station. Media criticism of the escapade led to him being brought before the Chief of the Air Staff, Group Captain Richard Williams, who rather than upbraiding Hewitt expressed himself "reservedly pleased about the publicity". After completing its survey work in November 1928, the unit served aboard the seaplane carrier HMAS Albatross.[9]

Hewitt's transfer to the Air Force was made permanent in April 1928.[3] Promoted to squadron leader, he became commanding officer of No. 101 Flight in February 1931,[3][10] and supervised embarkation of the Seagull aboard the cruiser HMAS Australia in September–October 1932.[11] Hewitt finished his tour with No. 101 Flight the following year, and was posted to Britain in 1934. He attended RAF Staff College, Andover, in his first year abroad, and served as Assistant Liaison Officer at Australia House, London, in 1935.[4] Although a specialist seaplane pilot, he converted to bombers in England, flying Hawker Hinds and Bristol Blenheims as commanding officer of No. 104 Squadron RAF from 1936.[1][12]

Hewitt was promoted wing commander in January 1938. Returning to Australia, he was appointed senior air staff officer (SASO) at RAAF Station Richmond, New South Wales, in June.[3] In May 1939, Hewitt was chosen to lead No. 10 Squadron, due to be formed on 1 July at the recently established RAAF Station Rathmines, near Lake Macquarie. He was preparing to depart for England to take delivery of the unit's planned complement of Short Sunderland flying boats when he broke his neck riding his motor cycle near Richmond, and had to forgo the assignment while he recovered. Fit for duty by August, he was given command of the Rathmines base to manage the deployment of No. 10 Squadron and its aircraft, but this was suspended due to the outbreak of World War II in September, and the Sunderlands and their RAAF crews remained in Britain for service alongside the RAF.[13]

World War II

Director of Personal Services to AOC No. 9 Operational Group

On 20 November 1939, the RAAF formed No. 1 Group in Melbourne,[14] which evolved into Southern Area Command early in 1940 with Hewitt as senior administration staff officer.[4][15] Having been promoted group captain in December 1939, Hewitt was made Director of Personal Services (DPS) at RAAF Headquarters in July 1940.[3] He was appointed an Officer of the Order of the British Empire on 11 July for his performance as SASO at Richmond.[3][16] Described by author Joyce Thompson as having "a Calvinist background and rigid ideas on women's place in society", as DPS Hewitt opposed the creation of the Women's Auxiliary Australian Air Force (WAAAF) and later advocated that its members be enrolled on a contractual basis rather than enlisted or commissioned as Permanent Air Force staff.[17] Promoted acting air commodore, he became Acting Deputy Chief of the Air Staff in October 1941.[3][18] In January 1942, he was posted to the staff of American-British-Dutch-Australian Command in the Dutch East Indies.[3] Hewitt served as Assistant Chief of the Air Staff in March and April before being assigned to the newly formed Allied Air Forces Headquarters (AAF HQ), South West Pacific Area (SWPA), as Director of Intelligence.[18][19] He established cordial working relations with his American peers at AAF HQ, becoming a confidant of its commander, Major General George Kenney.[2]

In February 1943, Hewitt was appointed Air Officer Commanding (AOC) No. 9 Operational Group (No. 9 OG).[20] The RAAF's main mobile strike force, No. 9 OG initially comprised seven Australian combat squadrons and came under the control of the US Fifth Air Force.[20][21] The month he took over, Hewitt's squadrons were reorganised into two wings based in New Guinea: No. 71 Wing, comprising units at Milne Bay, New Guinea, and No. 73 Wing, comprising those at Port Moresby.[22] In March, No. 9 OG led the RAAF's contribution to the Battle of the Bismarck Sea, "the decisive aerial engagement" in the SWPA according to General Douglas MacArthur, resulting in 12 Japanese ships being sunk.[23] Hewitt occasionally flew with his crews on operations, contrary to General Kenney's policy against commanders taking such risks.[24]

By April 1943, Hewitt had been dragged into the divisive personal conflict between the Chief of the Air Staff, Air Vice Marshal George Jones, and the AOC of RAAF Command, Air Vice Marshal Bill Bostock. RAAF Command was the Air Force's main operational formation in the Pacific, controlling 24 Australian squadrons. Jones, administrative and de jure head of the RAAF, sought to extend his authority into the sphere of operations by posting a "more accountable" officer into Bostock's position, namely Hewitt.[20][25] The Minister for Air, Arthur Drakeford, backed Jones' manoeuvre but was informed by Prime Minister John Curtin that MacArthur, as Supreme Commander SWPA, "would insist on the replacement of AVM Bostock by an equally able officer", and that "Air Commodore Hewitt ... was not considered an adequate replacement."[26] Hewitt recognised qualities in both Jones and Bostock, and tried not to take sides in their feud.[27]

No changes were made to command arrangements in the South West Pacific following this episode, and Hewitt continued to lead No. 9 OG in its bombing and strafing campaign against Japanese airfields and lines of communication in New Britain, north-east of New Guinea. By mid-June 1943, he had set up Group Headquarters at Milne Bay, and No. 73 Wing HQ at Goodenough Island. On 22 July, he mounted an operation against Gasmata airfield using 62 aircraft from five of his squadrons, the largest strike undertaken by the Australians to that date.[28] No. 9 OG would take most of the credit for the RAAF reaching a peak of 254 tons of bombs dropped in October, as against 137 tons delivered the previous month.[29] On 8 November, Hewitt sent out a formation of three Bristol Beauforts in a severe electrical storm to attack the heavily defended harbour at Rabaul. This was conceived as a "make or break" effort to prove the worth or otherwise of the Beaufort as a torpedo bomber, in which role it had so far been a disappointment; in what the official history of the RAAF in World War II described as "an heroic attack", at least one enemy tanker was struck, for the loss of one Beaufort.[30] The planning and execution of the raid led to conflict between Hewitt and the commanding officer of the Beaufort squadron, Wing Commander G. D. Nicoll, and Hewitt dismissed Nicoll shortly afterwards; the decision was swiftly reversed by Air Vice Marshal Jones.[3]

AOC No. 9 Operational Group to Air Member for Personnel

Although Hewitt was performing an "excellent job" according to Fifth Air Force commander Major General Ennis Whitehead, he was controversially removed from his post in mid-November 1943 by Jones, over accusations of poor discipline and morale within No. 9 OG.[20][31] RAAF historian Alan Stephens later described the circumstances of Hewitt's dismissal as "murky", and the allegations leading to it as unofficial.[20] Drakeford defended Hewitt's service record, informing the Prime Minister that "the present position may be largely, if not entirely, due to some temporary physical stress brought about by the strain of his important duties as A.O.C. of No. 9 Group."[31] Hewitt himself believed that he had been smeared by a disgruntled former staff officer;[2] historian Kristen Alexander identified Wing Commander Kenneth Ranger, who would play a leading part in the "Morotai Mutiny" of 1945, as having made allegations regarding Hewitt's supposed "lack of balance, vanity and lack of purpose in the prosecution of the war".[32] Hewitt returned to his previous position as Director of Intelligence at Allied Air Headquarters, and the Air Member of Personnel, Air Commodore Frank Lukis, took over as AOC No. 9 OG in December.[27] General Kenney considered Hewitt's removal "bad news".[20]

After completing his tour as Director of Intelligence at AAF HQ at the end of 1944, Hewitt became acting Air Member for Personnel (AMP) in 1945.[33] As AMP, Hewitt sat on the Air Board, the RAAF's controlling body that consisted of its most senior officers and was chaired by the Chief of the Air Staff.[34] Along with the other members of the board, he reviewed the findings of the inquiry by Justice John Vincent Barry into the "Morotai Mutiny", which had involved senior pilots of the Australian First Tactical Air Force (No. 1 TAF) attempting to resign their commissions to protest the relegation of RAAF fighter squadrons to strategically unimportant ground attack missions. Hewitt recommended that the AOC No. 1 TAF, Air Commodore Harry Cobby, be removed from command, along with his two senior staff officers. The majority of the Air Board saw no reason to take such action, leaving Hewitt to append a dissenting note to its decision. Drakeford supported Hewitt's position, and the three senior No. 1 TAF officers were later dismissed from their posts by Air Vice Marshal Jones.[32]

Post-war career

Demobilisation and rationalisation

Hewitt's appointment as Air Member for Personnel was made permanent following the end of World War II in August 1945.[33] In this role he was directly responsible for the demobilisation of what had become the world's fourth largest air force, and its transition to a much smaller peacetime service.[33][35] Hewitt considered that the RAAF was in danger of losing some of its best staff through rapid, unplanned demobilisation, and recommended that its workforce be stabilised for two years at a strength of 20,000 while it reviewed its post-war requirements. Although the Air Board supported Hewitt's proposal, government cost-cutting resulted in the strength of the so-called Interim Air Force remaining lower than planned, being reduced to some 13,000 by October 1946 and under 8,000 by the end of 1948.[36] Despite claiming that employing women in the Air Force was an important factor in reducing "antagonism and prejudice" against them in the work force in general, Hewitt also recommended that the WAAAF be disbanded after the war.[37]

As AMP, Hewitt was responsible for reviewing the potential employment of senior officers in the post-war Air Force. This review led to the early retirement of such figures as Air Marshal Richard Williams and Air Vice Marshals Stanley Goble, Bill Bostock, Frank McNamara, Bill Anderson, Henry Wrigley and Adrian Cole, ostensibly to make way for the advancement of younger and equally capable officers.[38][39] Hewitt helped draft the letters to each of the retirees, explaining the reasons for the decision and redundancy payments involved.[39] He was also responsible for rationalising the Air Force List of officers and their seniority that had become a source of numerous irregularities due to the temporary and acting promotions granted during wartime. This resulted in many officers of senior rank being demoted as many as three levels, such as group captain to flight lieutenant, in the first post-war List released in June 1947.[40]

RAAF education and other work

Hewitt was responsible for initiating major improvements in Air Force education that took place between 1945 and 1953, playing a key role in the establishment of RAAF College and the introduction of an apprenticeship training programme. The purpose of the College was, in Hewitt's words, to "sow the seeds of service" for future leaders, helping create a special RAAF esprit de corps. He added that it was "almost a truism that the future RAAF can be no better than the Air Force College".[41] Founded at Point Cook in January 1948, RAAF College's inaugural commandant was Air Commodore Val Hancock, who also drafted its first charter.[42] With the support of the Air Member for Engineering and Maintenance, Air Vice Marshal Ellis Wackett, Hewitt developed the Apprenticeship Training Scheme to raise the standard of technical roles in the Air Force, introducing it with a nationwide publicity campaign to attract recruits. Its base was the Ground Training School, which opened at Wagga, New South Wales, in early 1948 to provide education and technical training for youths aged 15 to 17. It was renamed RAAF Technical College in 1950 and the RAAF School of Technical Training in 1952.[43]

Parallel to his initiatives in Air Force education and training, Hewitt introduced a revised aircrew ranking scheme that consisted of skill categories with various levels, such as navigator level 4 or pilot level 1, rather than the regular military ranks such as sergeant or flight lieutenant. This was abandoned in 1950 due to dissatisfaction caused by the lack of obvious equivalence between these specialist "ranks" and the traditional ranking system common to the rest of the RAAF and other defence forces.[44] After completing his term as Air Member for Personnel in 1948, he was posted to London as the Australian Defence Representative.[4] By now promoted air vice marshal, Hewitt was appointed a Commander of the Order of the British Empire in the 1951 New Year Honours, in part for his leadership of No. 9 OG during the war.[3][45] Returning from Britain the same year, he took over as Air Member for Supply and Equipment (AMSE) from Air Vice Marshal George Mackinolty, who had died suddenly of cancer.[46][47] Hewitt served as AMSE until his retirement from the RAAF in April 1956.[1][47] In this role, he again cooperated with Air Vice Marshal Wackett—now the Air Member for Technical Services—to introduce the concept of acquiring spare parts based on "life-of-type", whereby the forecast number and type of spares necessary for an aircraft's projected service life would be ordered when it was first deployed operationally, to reduce support costs and delivery times.[48]

Later life and legacy

Following his retirement from the Air Force in 1956, Hewitt joined International Harvester Co. Australia as Manager of Education and Training. He became a trustee of the Services Canteen Trust the same year, serving in this position until 1977. Having retired from International Harvester in 1966, Hewitt became an author in later life and wrote two books on his experiences in the military.[4] The first, Adversity in Success, was published in 1980 and gave his account of the air war in the South West Pacific. He followed it in 1984 with The Black One. Hewitt also acted as chairman and managing director of his own publishing house, Langate Publishing.[1][4] Predeceased by his wife Lorna, he died in Melbourne on 1 November 1985, and was survived by his daughters.[3]

Historian Alan Stephens credits Hewitt with being primarily responsible for the "education revolution" that took place in the RAAF between 1945 and 1953, noting that Hewitt's initiatives while Air Member for Personnel were carried on by his successor in the position, Air Vice Marshal Frank Bladin.[49] According to Stephens and Jeff Isaacs, the importance of RAAF College and the Apprenticeship Training Scheme in contributing to the professionalism of the post-war service "cannot be over-stated".[1] Air Vice Marshal Ernie Hey, the Air Member for Technical Services from 1960 through 1972, declared that the apprenticeship programme was "one of the best things" the RAAF ever established and that its graduates—numbering some 5,500 from 1952 to 1993—were "absolutely outstanding".[50] Joe Hewitt is commemorated by Hewitt Reef in Great Barrier Reef Marine Park, named in his honour by the survey team on HMAS Moresby, with whom he worked as a member of No. 101 Flight in 1926–1928.[9] Hewitt also founded an eponymous trophy for small arms proficiency in the Air Force.[51][52]

Notes

- ^ a b c d e f g Stephens & Isaacs, High Fliers, pp. 97–99

- ^ a b c Dennis et al., Oxford Military History of Australia, p. 259

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Funnell, Ray. Hewitt, Joseph Eric (1901–1985). National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e f Draper, Who's Who in Australia 1985, p. 409

- ^ Gillison, Royal Australian Air Force, pp. 23–24

- ^ Stephens, The Royal Australian Air Force, p. 34

- ^ "No. 33048". The London Gazette. 19 May 1925. p. 3382.

- ^ "No. 33087". The London Gazette. 25 September 1925. p. 6206.

- ^ a b Coulthard-Clark, The Third Brother, pp. 408–411

- ^ Coulthard-Clark, The Third Brother, p. 218

- ^ Wilson, The Eagle and the Albatross, p. 27

- ^ Wilson, The Eagle and the Albatross, p. 51

- ^ Coulthard-Clark, The Third Brother, p. 150

- ^ Gillison, Royal Australian Air Force, p. 67

- ^ Gillison, Royal Australian Air Force, p. 92

- ^ "No. 34893". The London Gazette (Supplement). 9 July 1940. p. 4254.

- ^ Thomson, The WAAAF in Wartime Australia, pp. 58–59

- ^ a b Ashworth, How Not to Run an Air Force!, p. 295

- ^ Gillison, Royal Australian Air Force, p. 473

- ^ a b c d e f Stephens, The Royal Australian Air Force, pp. 122–123

- ^ Odgers, Air War Against Japan, p. 6

- ^ Odgers, Air War Against Japan, pp. 23–24

- ^ Stephens, The Royal Australian Air Force, pp. 160–165

- ^ Ashworth, How Not to Run an Air Force!, p. 211

- ^ Helson, Ten Years at the Top, pp. 122–126

- ^ Odgers, Air War Against Japan, pp. 16–18

- ^ a b Ashworth, How Not to Run an Air Force!, pp. 210–211

- ^ Odgers, Air War Against Japan, pp. 33–35

- ^ Odgers, Air War Against Japan, pp. 93–95

- ^ Odgers, Air War Against Japan, pp. 100–102

- ^ a b Odgers, Air War Against Japan, pp. 102–103

- ^ a b Alexander, "Cleaning the Augean stables"

- ^ a b c Helson, Ten Years at the Top, p. 224

- ^ Stephens, The Royal Australian Air Force, p. 112

- ^ Stephens, The Royal Australian Air Force, pp. 170–171

- ^ Stephens, The Royal Australian Air Force, pp. 176–179

- ^ Stephens, Going Solo, p. 335

- ^ Stephens, Going Solo, pp. 22–24

- ^ a b Helson, Ten Years at the Top, pp. 234–239

- ^ Stephens, Going Solo, pp. 24–25

- ^ Stephens, The Royal Australian Air Force, p. 186

- ^ Stephens, Going Solo, pp. 120–123

- ^ Stephens, Going Solo, pp. 129–131

- ^ Stephens, Going Solo, pp. 92–95

- ^ "No. 39105". The London Gazette (Supplement). 29 December 1950. p. 36.

- ^ Stephens & Isaacs, High Fliers, pp. 104–107

- ^ a b Stephens, Going Solo, p. 500

- ^ Stephens, Going Solo, p. 182

- ^ Stephens, Going Solo, p. 118

- ^ Stephens, The Royal Australian Air Force, pp. 191–192

- ^ "Air weapons contest at Canberra". The Canberra Times. Canberra. 4 December 1953. p. 2. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

- ^ "RAAF holds trophy shoot". The Age. Melbourne. 28 November 1960. p. 5. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

References

- Alexander, Kristen (2004). "'Cleaning the augean stables'. The Morotai Mutiny?". Sabretache. Military Historical Society of Australia.

- Ashworth, Norman (2000). How Not to Run an Air Force! Volume 1 – Narrative (PDF). Canberra: RAAF Air Power Studies Centre. ISBN 978-0-642-26550-0.

- Coulthard-Clark, Chris (1991). The Third Brother (PDF). North Sydney: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-0-04-442307-2.

- Dennis, Peter; Grey, Jeffrey; Morris, Ewan; Prior, Robin (2008) [1995]. The Oxford Companion to Australian Military History. South Melbourne, Victoria: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-551784-2.

- Draper, W. J. (ed.) (1985). Who's Who in Australia 1985. Melbourne: The Herald and Weekly Times. ISSN 0810-8226.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - Gillison, Douglas (1962). Australia in the War of 1939–1945: Series Three (Air) Volume I – Royal Australian Air Force 1939–1942. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 2000369.

- Helson, Peter (2006). Ten Years at the Top (Ph.D. thesis). Sydney: University of New South Wales. OCLC 225531223.

- Odgers, George (1968) [1957]. Australia in the War of 1939–1945: Series Three (Air) Volume II – Air War Against Japan 1943–45. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 1990609.

- Stephens, Alan (1995). Going Solo: The Royal Australian Air Force 1946–1971 (PDF). Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service. ISBN 978-0-644-42803-3.

- Stephens, Alan (2006) [2001]. The Royal Australian Air Force: A History. London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-555541-7.

- Stephens, Alan; Isaacs, Jeff (1996). High Fliers: Leaders of the Royal Australian Air Force. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service. ISBN 978-0-644-45682-1.

- Thomson, Joyce (1991). The WAAAF in Wartime Australia. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press. ISBN 978-0-522-84525-9.

- Wilson, David (2003). The Eagle and the Albatross: Australian Aerial Maritime Operations 1921–1971 (Ph.D. thesis). Sydney: University of New South Wales.

Further reading

- Hewitt, J. E. (1980). Adversity in Success. South Yarra, Victoria: Langate Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9594622-0-3.

- Hewitt, J. E. (1984). The Black One. South Yarra, Victoria: Langate Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9594622-1-0.

- 1901 births

- 1985 deaths

- Australian aviators

- Australian Commanders of the Order of the British Empire

- Graduates of the Royal Australian Naval College

- People from Victoria (Australia)

- Royal Australian Air Force air marshals

- Royal Australian Air Force personnel of World War II

- Royal Australian Navy officers

- 20th-century Australian people