133rd Armored Division "Littorio"

| 133rd Armoured Division Littorio | |

|---|---|

133a Armoured Division Littorio Insignia | |

| Active | 1939–1943 |

| Country | Italy |

| Branch | Italian Army |

| Type | Armoured |

| Size | Division |

| Part of | Italian XX Motorised Corps German-Italian Panzer Army |

| Nickname(s) | Littorio |

| Engagements | World War II Italian invasion of France Invasion of Yugoslavia First Battle of El Alamein Battle of Alam el Halfa Second Battle of El Alamein |

133rd Armoured Division Littorio or 133° Divisione Corazzata Littorio (Italian) was an armoured division of the Italian Army during World War II. The division was formed in 1939 from the Infantry Division Littorio (4 Infantry Division Littorio) that had taken part in the Spanish Civil War. It was a reserve unit during the invasion of France when it attacked through the Little St Bernard Pass, which was halted by the French defenders. It then took part in the Invasion of Yugoslavia, fighting at Mostar and Trebinje. It was sent to North Africa in the spring of 1942 where it fought until it was destroyed at the Second battle of El Alamein in November 1942.

Formation

133rd Armoured Division Littorio was the third Italian armoured division formed, after the 131 Armoured Division Centauro and the 132 Armoured Division Ariete The original Littorio Division had fought in the Spanish Civil War as a unit of regular army Volunteers. When they returned to Italy early in 1939, the division was converted to an armoured division but kept the fascist-inspired name Littorio [nb 1] The new Armoured Division had four Tank battalions, three Infantry battalions and two Artillery Regiments.[2]

Italian invasion of France

During the Italian invasion of France, the Italian forces numbered about 700,000 troops. However, while they enjoyed a huge numerical superiority to the French, they had several deficiencies. The Italian armoured regiments from the Littorio had between 150 to 250 L3/35 tanks each. But these vehicles were often classified as "tankettes" and were little more than lightly armoured machine-gun carriers not suited for modern warfare.[3]

On 20 June, the Italian campaign began and on 21 June,[4] troops of the Italian Royal Army crossed the French border in three places The Italians attacked in two directions. One force attempted to advance through the Alps and another force attempted to advance along the Mediterranean coast towards Nice. Initially, the Italian offensive enjoyed a limited level of success. The French defensive lines on the Italian border were weakened due to French High Command shuffling forces to fight the Germans. Some French mountain units had been sent to Norway. However, the Italian offensive soon stalled at the fortified Alpine Line in the Alps region and at the southern end of the Maginot Line in the Mediterranean region.

Yugoslavia

The Division was part of the Italian Second Army that faced the Yugoslavian Seventh Army. The Italians encountered limited resistance and occupied parts of Slovenia, Croatia, and the coast of Dalmatia.[1][2]

Western Desert

The Littorio was never intended for desert operations, but due to the situation in the Western Desert (eastern Libya and western Egypt) the requirement for mobile formations had become urgent. The second Italian armoured division Ariete Division, was already in the desert.[1]

The first units of the Littorio arrived in Tripoli, the capital and major port of Libya, in early January 1942, but had to wait until March for the complete division to arrive.[1]

Notably the Semovente da 75/18 self-propelled gun had equipped the Littorio a somewhat wider tactical repertoire,[5] until British deployment of U.S. medium tanks negated that small advantage.

By April, the division had reached Benghazi, but the division’s transport had been diverted to carry much needed supplies to combat units at the Gazala line. Littorio did not participate in the Battle of Gazala, though British accounts usually include its troop and tank strengths in the Axis total. A small battlegroup arrived at the front on 20 June, and participated in the attack on Tobruk. The division was a part of the investing force at Mersa Matruh, and pursued 8th Army in its retreat to El Alamein. In this advance the division was harassed by the Desert Air Force, as all the Axis formations were, and it became engaged in a number of running fights with the 1st Armoured Division. By the time it reached El Alamein its armour had been lost.

First Battle of El Alamein

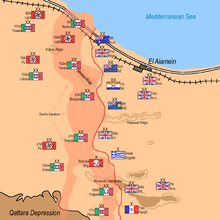

In the First Battle of El Alamein, the German commander Erwin Rommel's planned for the 90th Light Division, 15th Panzer Division and 21st Panzer Division to penetrate the Eighth Army lines between the Alamein box and Deir el Abyad. 90th Light was then to veer north to cut the coastal road and trap the Alamein box defenders and the Afrika Korps would veer right to attack the rear of XIII Corps. The Ariete division would then attack the Alamein box from the west. The Italian XX Corps was to follow the Afrika Korps and deal with the Qattara box while the Italian Littoro Armoured Division and German reconnaissance units would protect the right flank[6]

Battle of Alam el Halfa

In the Battle of Alam el Halfa the Littorio were now part of the Italian XX Motorised Corps which also included the Italian 101 Motorised Division Trieste and the 132 Armoured Division Ariete.

The German attack started at dawn but was quickly stopped by a flank attack from British 8th Armoured brigade. The Germans suffered little, as the British were under orders to spare their tanks for the coming offensive but they could make no headway either and were heavily shelled.[7] Meanwhile the Littorio and Ariete Armoured Divisions had moved up on the left of the Afrika Korps and the 90th Light Division and elements of Italian X Corps had drawn up to face the southern flank of the New Zealand box.[8] Under constant air raids throughout the day and night and on the morning of 2 September, realizing his offensive had failed and that staying in the salient would only add to his losses, Rommel decided to withdraw.[9]

Second Battle of El Alamein

The Second Battle of El Alamein is usually divided into five phases, consisting of the break-in (23 to 24 October), the crumbling (24 to 25 October), the counter (26 to 28 October), Operation Supercharge (1 to 2 November) and the breakout (3 to 7 November). No name is given to the period from 29 to 31 October when the battle was at a standstill.

25 October

The Littorio was held in reserve behind the Infantry divisions to the rear of Miteirya Ridge on the 25 October the Axis forces launched a series of attacks using 15th Panzer and Littorio divisions. The Panzerarmee was probing for a weakness, but found none. When the sun set the Allied infantry went on the attack and around midnight 51st (Highland) Division launched three attacks, but no one knew exactly where they were. Pandemonium and carnage ensued, resulting in the loss of over 500 Allied troops, and leaving only one officer among the attacking forces. By this time the Trento Division had lost half its infantry and most of its artillery, 164th Light Afrika Division had lost two battalions and although the 15th Panzer and Littorio Divisions had held off the Allied armour, this had proved costly and most units were under strength.[10] Rommel was convinced by this time that the main assault would be in the north[11] and was determined to retake Point 29. He ordered a counterattack against Point 29 by 15th Panzer, 164th Light Africa Divisions and elements of Italian XX Corps to begin at 1500 Hrs but under heavy artillery and air attack this came to nothing.[12] During the day he also started to draw his reserves to what was becoming the focal point of the battle: 21st Panzer and part of the Ariete moved north during the night to reinforce the 15th Panzer and Littorio Divisions and 90th Light Division at El Daba were ordered forward while the Trieste Division were ordered from Fuka to replace them. 21st Panzer and the Ariete made slow progress during the night as they were heavily bombed[13]

2 November

At 1100Hrs on 2 November The remains of 15th Panzer, 21st Panzer and Littorio Armoured Divisions counterattacked the British 1st Armoured Division and the remains of British 9th Armoured Brigade, which by that time had dug in with a screen of anti-tank guns and artillery together with intensive air support. The counter-attack failed under a blanket of shells and bombs, resulting in a loss of some 100 tanks.[14] Fighting continued throughout 3 November but the British 2nd Armoured Brigade were held by elements of the Afrika Korps and tanks of the Littorio.[15]

4 November

The 4 November saw the destruction of the Littorio, Ariete and the Trieste Motorised Division which were attacked by the British 1st and 10th Armoured Divisions. Berlin radio claimed that in this sector the "British were made to pay for their penetration with enormous losses in men and material. The Italians fought to the last man."[16] Private Sid Martindale, 1st Battalion Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders, wrote:

There was not much action to see but we came across lots of burnt out Italian tanks that had been destroyed by our tanks. I had never seen a battlefield before and the site [sic] of so many dead was sickening.[17]

Harry Zinder of Time magazine noted that the Italians fought better than had been expected, and commented that for the Italians:

It was a terrific letdown by their German allies. They had fought a good fight. In the south, the famed Folgore parachute division fought to the last round of ammunition. Two armoured divisions and a motorised division, which had been interspersed among the German formations, thought they would be allowed to retire gracefully with Rommel's 21st, 15th and 19th [sic][nb 2] light. But even that was denied them. When it became obvious to Rommel that there would be little chance to hold anything between El Daba and the frontier, his Panzers dissolved, disintegrated and turned tail, leaving the Italians to fight a rear-guard action.[18]

Aftermath

The German records after the Battle for the 28 October reveal the three divisions most affected, 15th Panzer, 21st Panzer and Littorio, were 271 tanks down on the total with which they had started the battle on the 23 October. This figure includes tanks out of action through mechanical failure as well as through mines or other battle damage, but by this time repairs and replacements were hardly keeping pace with daily losses. The surviving enemy tank states indicate that from the 28th to the 31st the two German divisions found it difficult to muster 100 tanks in running order between them, while Littorio had between 30 and 40.[19]

Commander

Order of battle

Order of Battle of the 133rd Littorio on October 23, 1942

- Division Headquarters

- Division Headquarters Company

III Cavalry Squadron (Reconnaissance Battalion) Lancieri di Novara

III Cavalry Squadron (Reconnaissance Battalion) Lancieri di Novara 133rd Armoured Infantry Regiment

133rd Armoured Infantry Regiment

- Regiment Headquarters Company

- IV Armoured Battalion

- XII Armoured Battalion

- LI Armoured Battalion

12th Bersaglieri Regiment

12th Bersaglieri Regiment

- Regiment Headquarters Company

- XXI Bersaglieri Motorcycle Battalion

- XXIII Bersaglieri Motorized Battalion

- XXXVI Bersaglieri Motorized Battalion

- Anti-tank Company

3rd Artillery Regiment

3rd Artillery Regiment

- Regiment Headquarters Company

- II Artillery Group, 133 Artillery Regiment

- CCCII Artillery Group

- DLIV Self-propelled Artillery Group

- DLVI Self-propelled Artillery Group

- XXIX Anti-Air Artillery Group

- Engineer Battalion

Notes

- Footnotes

- ^ literally “lictor”; in ancient Rome, the lictors carried the fasces, those rod-and-axes symbols of state power adopted by Benito Mussolini two millennia later.[1]

- ^ Presumably a confused reference to the 90th Light Division. There was no 19th Light Division on the German Order of Battle

- Citations

- ^ a b c d Bennighof, Mike (2008). "Littorio at Gazala". Avalanche Press. Archived from the original on 2009-04-30. Retrieved 2009-04-06.

- ^ a b Wendal, Marcus. "Italian Army". Axis History. Archived from the original on 2009-04-30. Retrieved 2009-06-04.

- ^ Iron Arm – Sweet, John Joseph Timothy; Stackpole Books, 2007, Page 84)

- ^ Jowett, Philip S. The Italian Army 1940–45 (1): Europe 1940–1943. Osprey, Oxford – New York, 2000, pg. 5, ISBN 978-1-85532-864-8

- ^ Knox, MacGregor (November 2000). Hitler's Italian Allies, Royal Armed Forces, Fascist Regime, and the war of 1940-1943. Cambridge University Press. pp. 153. ISBN 9780521790475.

- ^ Playfair Vol. III, p. 340

- ^ Fraser, p. 359.

- ^ Playfair, p. 387.

- ^ Carver, p. 67.

- ^ Playfair, P. 50.

- ^ Watson (2007), p.23

- ^ Playfair, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Playfair, p. 51.

- ^ Watson, p. 24.

- ^ Playfair, p. 71.

- ^ "Desert War, Note (11): Statement issued by the German Government on 6 November 1942". spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk. Archived from the original on 30 April 2009. Retrieved 2007-12-22.

- ^ Spirit, Martin; Martindale, Sid (2005). "Sid's War: The Story of an Argyll at War". Archived from the original on 2009-04-30. Retrieved 2008-01-27.

- ^ Zinder, Harry (16 November 1942). "A Pint of Water per Man". Time Magazine (16 November 1942). Retrieved 18 April 2010.

- ^ "Alam Halfa and Alamein, Chapter 27 — The Fourth Day of Battle, pp 356–357". New Zealand electronic text centre.

- Carver, Field Marshal Lord (2000) [1962]. El Alamein (New ed.). Ware, Herts. UK: Wordsworth Editions. ISBN 978-1-84022-220-3.

- Playfair, Major-General I.S.O.; and Molony, Brigadier C.J.C.; with Flynn R.N., Captain F.C.; Gleave, Group Captain T.P. (2004) [1st. pub. HMSO 1966]. Butler, J.R.M (ed.). The Mediterranean and Middle East, Volume IV: The Destruction of the Axis Forces in Africa. History of the Second World War United Kingdom Military Series. Uckfield, UK: Naval & Military Press. ISBN 1-84574-068-8.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - Watson, Bruce Allen (2007) [1999]. Exit Rommel: The Tunisian Campaign, 1942–43. Mechanicsburg PA: Stackpole. ISBN 0-8117-3381-5.

Further reading

- George F. Nafziger – Italian Order of Battle: An organizational history of the Italian Army in World War II (3 vol)

- John Joseph Timothy Sweet – Iron Arm: The Mechanization of Mussolini's Army, 1920–1940