William Thomas Hamilton (frontiersman)

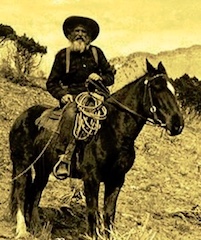

William Thomas Hamilton (December 6, 1822 – May 24, 1908), also known as Wildcat Bill, was an English-born American frontiersman and author.

Life

Hamilton was born in the River Till area, Northern England on December 6, 1822. His parents, Margaret and Alexander Hamilton, emigrated to the United States[1] from Scotland[2] when he was a baby. He was raised in St. Louis, Missouri and attended school for five years.[1] The son of financially comfortable parents, he grew up on a farm and learned to shoot a weapon and ride a horse.[2]

Career

In the death of "Uncle Billy" Hamilton the United States loses its greatest Indian fighter and most skillful Indian sign talker and sign reader that this country ever produced.

Few men had the adventurous career that was Hamilton's, although because of a modesty that rarely permitted him to talk of himself, comparatively few persons knew his record on the plains.

He has been described as a mountain man, trapper, and scout of the American West,[3][4] living in the mountains for more than 50 years. He was given the name Wildcat Bill by Native Americans.[5] He was considered a healer among Native Americans. Also called Sign Man, he excelled in Native American sign language according to Favour.[1]

Hamilton left Missouri for the mountains to improve his health[6] in 1842 with Old Bill Williams, whom he worked with and became a companion. He was a trapper and trader for six years.[7] His father bought a third interest in the trapping enterprise led by Williams.[2] With the California Gold Rush,[2] he moved in 1848 to Hangtown, California, where he married and had a child. In 1851, both his wife and child died.[1] After protecting miners from Native Americans with the Buckskin Rangers in California, Hamilton worked for the government protecting pioneers from Native Americans in Nevada, Oregon and Montana[1][7] and was a scout for George Armstrong Custer[2] from the 1850s through the 1870s. During that time period, he also worked as a trader at Fort Benton,[1][7] along Rattlesnake Creek at the site of what is now Missoula, and at Flathead Lake, all in Montana.[2][8] He was also the Chouteau County, Montana sheriff and a U.S. Marshal.[1][7] Continuing his work for the government, he worked with the Blackfoot People in 1873. Three years later he fought the Sioux in the Great Sioux War of 1876 with General George Crook.[7]

Hamilton lived many years in Montana and trapped and hunted throughout the Yellowstone area, before it was officially discovered. In Montana Territory (1864–1889) and state, he was commonly known as Uncle Billy.[2] He assisted the Smithsonian Institution in translating pictures of hundreds of Native American signs painted on the cliffs along Lake Flathead.[2]

In his later years, he was a guide and hunter.[7] Hamilton was living in Columbus, Montana by 1903 when he was one of the co-founders of the Pioneers of Eastern Montana.[9] Along with Old Bill Williams, Hamilton worked and was friends of John Bozeman and Jim Bridger.[2]

Death

He died of stomach cancer on May 24, 1908 in a hospital in Billings, Montana[1][2] and was buried in Columbus, Montana.[2]

Bibliography

His books include:

- My sixty years on the plains: trapping, trading, and Indian fighting. Forest and Stream Pub. Co. 1905.

- Spying on the Blackfoot: A Mountain Man's Secret Mission Across the Rockies Into Blackfoot Country

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h Alpheus Hoyt Favour (1962). Old Bill Williams, Mountain Man. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 140. ISBN 978-0-8061-1698-3.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Hero of Many Battles Dead". The Butte Daily Post. May 26, 1908. pp. 1, 8 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "World Facts Briefly Told". The Kokomo Tribune. December 7, 1946. Retrieved May 21, 2018 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "William Thomas Hamilton – American mountain man". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ^ "Peculiar Names: Customs of the Whites and Indians in the West". The Billings Weekly Gazette. April 23, 1891. p. 1. Retrieved May 20, 2018 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Today's Anniversaries". Wausau Daily Herald. December 6, 1935. p. 5. Retrieved May 21, 2018 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f Joseph Norman Heard (1987). Handbook of the American Frontier: The far west. Scarecrow Press. pp. 128–129. ISBN 978-0-8108-3283-1.

- ^ Allan James Mathews (2002). A Guide to Historic Missoula. Montana Historical Society. p. 164. ISBN 978-0-917298-89-9.

- ^ "Society of Pioneers of Eastern Montana Elects Officers". The Billings Weekly Gazette. October 2, 1903. p. 3. Retrieved May 21, 2018 – via newspapers.com.

Further reading

- Federal Writers' Project (23 October 2013). The WPA Guide to Montana: The Big Sky State. Trinity University Press. p. 174. ISBN 978-1-59534-224-9.

- Forest and Stream. Forest and Stream Publishing Company. 1905. pp. 347–348.

- Paul T. Hellmann (14 February 2006). Historical Gazetteer of the United States. Routledge. p. 657. ISBN 1-135-94859-3.

- W. C. Jameson (1993). Buried Treasures of the Rocky Mountain West: Legends of Lost Mines, Train Robbery Gold, Caves of Forgotten Riches, and Indians' Buried Silver. august house. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-87483-272-3.