Machine de Marly

| Machine de Marly | |

|---|---|

| Classification | Water pump |

| Application | Irrigation |

| Fuel source | Hydropower |

| Components | 14 paddle wheels 11.9m in diameter 250 pumps Various dams and linkages |

| Inventor | Arnold de Ville, Rennequin and Paulus Sualem |

| Invented | 1681-1684 |

The Machine de Marly, also known as the Marly Machine or the Machine of Marly, was a large hydraulic system in Yvelines, France, built in 1684 to pump water from the river Seine and deliver it to the Palace of Versailles.[1]

King Louis XIV needed a large water supply for his fountains at Versailles. Before the Marly Machine was built, the amount of water delivered to Versailles already exceeded that used by the city of Paris, but this was insufficient, and fountain-rationing was necessary.[2] Ironically[clarification needed] most of the water pumped by the Marly Machine ended up being used to develop a new garden at the Château de Marly. However, even if all the water pumped at Marly (an average of 3,200 cubic metres per day, or 845,351 gallons per day) had been supplied to Versailles, it still would not have been enough: the fountains running à l'ordinaire (that is, at half pressure) required at least four times as much.[1]

The Machine de Marly, based on a prototype at the Château de Modave, consisted of fourteen gigantic water wheels, each roughly 11.5 meters or 38 feet in diameter,[3] that powered more than 250 pumps to bring water 162 metres (177 yd) up a hillside from the Seine River to the Louveciennes Aqueduct. Louis XIV had countless schemes and inventions that were supposed to bring water to his fountains. The Machine de Marly was by far his most extensive and costly plan. After three years of construction and a cost of approximately 5,500,000 livres, the massive contraption, considered the most complex of the 17th century, was completed. "The chief engineer for the project was Arnold de Ville and the 'contractor' was Rennequin Sualem (after whom the quai by the machine is now named)."[3] Both men had experience in pumping water from coal mines in the region of Liège (in modern Belgium).[4]

The machine suffered from frequent breakdowns, required a permanent staff of sixty to maintain and often required costly repairs. It functioned for 133 years. Destroyed in 1817, it was replaced by a "machine temporaire" during 10 years and then a steam engine entered in service from 1827 to 1859. From 1859 to 1963, the pumping at Marly was assumed by another hydraulic machine conceived by the engineer Xavier Dufrayer.[5] Dufrayer's machine was scrapped in 1968 and replaced by electromechanical pumps.

Historical context

From the beginning, the construction of the château and the park of Versailles water supply had posed a problem. The site chosen by Louis XIV, a former hunting lodge of Louis XIII, was far removed from any river and high in elevation. The sovereign's will to have a park with more and more basins, water jets and fountains became a hallmark of his reign by the extension and improvement of a permanent water supply system with the construction of new pumps, aqueducts and reservoirs to collect ever more water, from a greater and greater distance.

The idea to bring water from the Seine to Versailles had always been under consideration. But more than just the distance - the river is located nearly 10 km from the château - there was the problem of the elevation to ascend, nearly 150 meters (490 feet). Since 1670, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, Louis XIV's Superintendent of the King's Buildings, had opposed several projects, including one proposed by Jacques de Manse, both for reasons of feasibility and that of cost.[6]

Arnold de Ville (1653-1722), a young and ambitious bourgeois of Huy in the Province of Liège, who had already built a pump in Saint-Maur, succeeded in submitting to the king his project for pumping the waters of the River Seine to the Château of Val in the forest of Saint-Germain, demonstrating that the same could be done to supply Versailles. This machine, a sort of small scale model of what the Machine of Marly could be, impressed the king,[7] who then entrusted him with the development of a machine on the Seine to supply not only the gardens of Versailles, but also those of the Chateau of Marly then under construction.[6]

Location

The Machine de Marly site is located 7 km (4.4 mi) north of the Château de Versailles and 16.3 km (10.2 mi) west of the center of Paris, on the Seine in the Yvelines department. The river pumps and administration buildings are located in what is now the town of Bougival; relay pumps, machinery, the aqueduct and reservoirs are located in Louveciennes. One reservoir is in the town of Marly-le-Roi.

Between Port-Marly and Bezons, the Seine, along its length, was divided into two arms by a series of islands and earth berms linked together by timber/rock dikes to form two disconnected, parallel river beds over ten kilometers in length. The hydraulic pumping machinery, propelling the river water to the top of the hill that borders the Seine, was constructed across from the left arm of the river, a little below the small village of La Chaussée, downstream of Bougival. [8] A dam at Bezons on the right arm creates a hydraulic head measuring 3.1 meters (10 feet 2 inches) high to power the wheels of the Machine de Marly.[9] The upper pumping relay station (demolished) was located next to the Château des Eaux (1700) and pumped water to the top of the Louveciennes aqueduct, which fed the Louveciennes and Marly reservoirs, near the site of the Château de Marly (demolished).

-

Location of the Machine de Marly

-

Location of the components of the Machine de Marly (detail)

-

The Seine between Bezons and the Machine de Marly showing the linkage between islands created by dikes to establish the water head at the Machine

-

Dike at Chatou, plan, section and elevation (1763-1765)

Construction

It does not seem that one has ever completed a machine that has made as much noise in the world as that of Marly...

To design and build this machine, Arnold de Ville, who did not have the technical skills, appealed to two men from Liège, the master carpenter and mechanic Rennequin Sualem (1645-1708) and his brother Paulus. He had already worked with them on a pump at the Château de Modave and Rennequin Sualem was the designer of the pump at the Château de Val. The entire project – channeling and dikes on the Seine, construction of the machine and the network of aqueducts and basins – would last for 6 years. The chosen site on the Seine would later become the town of Bougival (at the location of the current locks of Bougival).

About 7 kilometers upstream, Colbert channeled a portion of the Seine by linking several islands with dikes from the island of Bezons and separating the river into two arms, a western arm for navigation and an eastern arm destined to supply the machine by creating a constriction and a drop[6] of about three meters[7] to power the 14 paddle wheels of the machine. The construction mobilized 1800 workers and required more than 100,000 tons of wood, 17,000 tons of iron and 800 tons of lead and as much cast iron.[7] The wood used in the construction of the platform and the wheels of the machine, and for the dikes between the islands and for the buildings came from the surrounding forests. The iron for rods came from the Nivernais and Champagne and most of the cast iron pipe was produced in Normandy.[6]

A large number of Walloons came to work on the project. They possessed a know-how acquired from their work on water evacuation from mines. Many defected as well because of the economic difficulties encountered then in Wallonia, which had been ravaged by wars. Illiterate, the Sualem brothers were from a family of master carpenters from the mines of Liège. They were the only ones to have mastered the mechanism for remote power transmission, the flatrod system necessary for the proper functioning of the machine of Marly. The Walloon craftsmen went on to become the primary maintenance men essential for the enormous task of keeping the machine in working order.[6]

-

Map of 1783 showing the deviation of the Seine

-

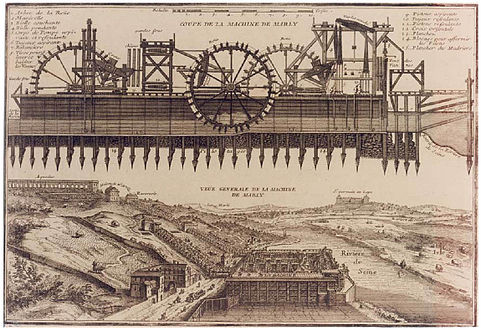

Elevation and perspective of the Machine de Marly (c. 1715) by Nicolas de Fer

The work began in June 1681 with the canalization of the Seine. The construction of the machine began at the end of 1681. On June 14, 1682, a successful demonstration was held in the presence of Louis XIV.[6] The water could be elevated to the top of the hillside. The machine was inaugurated June 13, 1684[7] by the king and his court. The aqueduc de Louveciennes was completed in 1685 and the entire project, three years later, in 1688.

The total cost of the project was 5.5 million livres tournois (over 100 million dollars 2015 [11]). It included the construction of the machine itself (3,859,583 livres), buildings, aqueducts and water basins, the supply of materials, and the wages of the workers and artisans. (Rennequin Sualem was the best paid with 1800 pounds per year.).[6] After the end of the work and the successful demonstration, Rennequin Sualem was appointed First Engineer of the King by Louis XIV and knighted. To the king, who asked him how he had had the idea of this machine, Rennequin answered in Walloon: "Tot tuzant, Sire" ("By thinking hard, Sire").[12] Arnold de Ville earned a great deal of money from the success of the machine and was able to rise into the aristocracy.[6]

Description

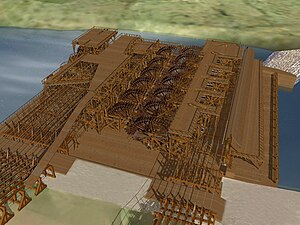

The engraving illustrated here describes the functioning of the machine as follows:

THE MACHINE OF MARLY is built on an arm of the Seine river. It consists of 14 wheels of 30 feet [11.9 m; 39 English feet] in diameter, the axles of which have two cranks, one which moves the pistons which push the water into the pipes and raise it up to the first reservoir; the other moves a system of crossarm levers which run the length of the mountain up to the highest reservoir. These crossarms power the pumps which are in the reservoirs and pump the water from the lower reservoir to the upper and from there to the top of the tower which is at the summit of the mountain, from where it runs over a large aqueduct which feeds different pipes to furnish all the waters of Versailles and Marly.

Pumping technology of the era of Louis XIV did not allow the delivery of water from the Seine to the top of the aqueduct of Louveciennes, an elevation differential of more than 150 meters (490 feet) in just one stage, so two intermediate pump relay stations were built, one at 48 meters (156 feet) and another at 99 meters (322 feet) above the river. Pumps in the relay locations were powered by two sets of oscillating timber and metal tie-rod linkages, driven by the river paddle wheels. A reservoir at each station buffered the water supply for each level of pumps.

-

Computer animation of a typical wheel showing pumps and crank linkage][13]

-

Looking southwest

-

Looking northeast

-

Detail

Remnants

Some remnants of Dufrayer's machine are still visible today, but little remains of the original 17th-century masterpiece built by the Sualem brothers, de Ville and Louis XIV.

The overgrown walls of the mid-slope reservoir are visible on the hillside, just adjacent to the cobblestone path that runs straight up the incline. The paving stones on this 17th century service road are set with their top edges slightly exposed to allow better traction for the horses which hauled loads uphill.

Two administration buildings from the original Machine complex of 1684 still exist next to the Seine.[14]

The building which housed the steam-driven pumping machine from 1825 can still be seen next to the river as well.

An engraving of the Paris Observatory from the beginning of the eighteenth century shows the wooden "Marly tower" on the right, a dismantled part of the Machine de Marly (the temporary tower replaced by La tour du Levant at the beginning of the Aqueduc de Louveciennes), moved to the Paris Observatory by astronomer Giovanni Domenico Cassini for mounting long telescopes.[15]

-

Remnants of the mid-slope reservoir of the original Marly Machine

-

Charles X building from 1825

-

Marly tower at the Paris Observatory

Notes

- ^ a b Thompson 2006, p. 251.

- ^ Thompson 2006, p. 251 and note on p. 351 ("Even though more ..."), citing Adams 1979, p. 88.

- ^ a b Pendery 2004.

- ^ Demoulin & Kupper 2004, p. 199.

- ^ Barbet 1907, p. 166, note 3.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Bentz & Soullard 2011.

- ^ a b c d Testard-Vallant 2010, pp. 70–71.

- ^ Barbet 1907, p. 95.

- ^ Barbet 1907, p. 101.

- ^ Bélidor 1739, p. 195: "Il ne paroît pas que l'on ait jamais exécuté de machine qui ait fait autant de bruit dans le monde que celle de Marly..."

- ^ Tiberghien 2002, p. 12.

- ^ "Rennequin Sualem" of: "Famous Belgians"

- ^ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8Qzp3rcMfWs

- ^ Entry PA00087379 (in French), website of the French Monuments historiques.

- ^ Barbet 1907, p. 124.

Bibliography

- Adams, W. H. (1979). The French Garden 1500–1800. New York: Braziller. ISBN 9780807609187.

- Barbet, Louis-Alexandre (1907). Les grandes eaux de Versailles: installations mécaniques et étangs artificiels: description des fontaines et de leurs origines. Paris: H. Dounod et E. Pinat. Copy at Google Books.

- Bélidor, Bernard Forest de (1739). Architecture Hydraulique, ou L'art de conduire, d'élever et de ménager les eaux pour les différens besoins de la vie, Tome Second. Paris: L. Cellot. Copy at Gallica.

- Bentz, Bruno; Soullard, Éric (2011). "La Machine de Marly", Château de Versailles: de l'Ancien régime à nos jours, no. 1 (April/June 2011), pp. 73–77. ISSN 2116-0953. Notice bibliographique at BnF.

- Demoulin, Bruno; Kupper, Jean-Louis (2004). Histoire de la Wallonie. Toulouse: Privat. ISBN 9782708947795.

- Pendery, David (2014). "La Machine de Marly" at www.marlymachine.org. Archive copy (17 December 2014) at the Wayback Machine.

- Testard-Vaillant, Philippe (2010). "Des grands travaux en cascade". Les sciences au Château de Versailles (exhibition catalogue in French), pp. 70–71. Issy-les-Moulineaux: Mandadori magazines France. OCLC 758856411. ISSN 1968-7141.

- Thompson, Ian (2006). The Sun King's Garden: Louis XIV, André Le Nôtre and the Creation of the Gardens of Versailles. London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 9781582346311.

- Tiberghien, Frédéric (2002). Versailles, le chantier de Louis XIV: 1662–1715. [Paris]: Perrin. ISBN 9782262019266.

![Computer animation of a typical wheel showing pumps and crank linkage][13]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/56/Machineanim1.JPG/359px-Machineanim1.JPG)