Rack (torture)

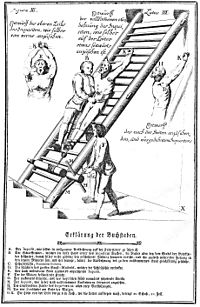

The rack is a torture device consisting of a rectangular, usually wooden frame, slightly raised from the ground,[1] with a roller at one or both ends. The victim's ankles are fastened to one roller and the wrists are chained to the other. As the interrogation progresses, a handle and ratchet mechanism attached to the top roller are used to very gradually retract the chains, slowly increasing the strain on the prisoner's shoulders, hips, knees, and elbows and causing excruciating pain. By means of pulleys and levers this roller could be rotated on its own axis, thus straining the ropes until the sufferer's joints were dislocated[1] and eventually separated. Additionally, if muscle fibres are stretched excessively, they lose their ability to contract, rendering them ineffective.[citation needed]

One gruesome aspect of being stretched too far on the rack is the loud popping noises made by snapping cartilage, ligaments or bones.[citation needed] One powerful method for putting pressure upon prisoners was to force them to watch someone else being subjected to the rack.[citation needed] Confining the prisoner on the rack enabled further tortures to be simultaneously applied, typically including burning the flanks with hot torches or candles or using "pincers made with specially roughened grips to tear out the nails of the fingers and toes"[2] or sliding thin slivers of red-hot coal between pairs of adjacent toes.[3] Usually, the victim's shoulders and hips would be separated and their elbows, knees, wrists, and ankles would be dislocated.[citation needed]

Uses

Early use

The rack was first used in antiquity and it is unclear exactly from which civilization it originated, though some of the earliest examples are from Greece. The Greeks may have first used the rack as a means of torturing slaves and non-citizens, and later in special cases, as in 356 BC, when it was applied to gain a confession from Herostratus, who was later executed for burning down the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.[4] Arrian's Anabasis of Alexander states that Alexander the Great had the pages who conspired in his assassination, and their mentor, his court historian Callisthenes, tortured on the rack in 328 BC.[5]

According to Tacitus, the rack was used in a vain attempt to extract the names of the conspirators to assassinate Emperor Nero in the Pisonian conspiracy from the freedwoman Epicharis in 65 A.D. The next day, after refusing to talk, she was being dragged back to the rack on a chair (all of her limbs were dislocated, so she could not stand), but strangled herself on a loop of cord on the back of the chair on the way.[6]

The rack was also used on early Christians, such as St. Vincent (304 A.D.), and mentioned by the Church Fathers Tertullian and St. Jerome (420 A.D.).[7]

Britain

Its first appearance in England is said to have been due to John Holland, 2nd Duke of Exeter, the constable of the Tower in 1447, whence it was popularly known as the Duke of Exeter's daughter.[1]

The Catholic martyr Saint Nicholas Owen, a noted builder of priest holes, died under torture on the rack in the Tower of London in 1606. Guy Fawkes is also thought to have been put to the rack, since a royal warrant authorising his torture survives. The warrant states that the "lesser tortures" should be applied to him first, but that if he remained recalcitrant he could be racked.

In 1615 a clergyman called Edmund Peacham, accused of high treason, was racked.

In 1628 the question of its legality was raised by a proposal in the Privy Council to rack John Felton, the assassin of the Duke of Buckingham.[1] The judges resisted this, unanimously declaring its use to be contrary to the laws of England.[1] The previous year Charles I had authorised the Irish Courts to rack a Catholic priest; this seems to have been the last time the rack was used in Ireland.

In 1679 Miles Prance, a silversmith who was being questioned about the murder of the respected magistrate Sir Edmund Berry Godfrey, was threatened with the rack, although it is unlikely that the threat was a serious one.

Russia

In Russia up to the 18th century the rack (дыба, dyba) was a gallows-like device for suspending the victims (strappado). The suspended victims were whipped with a knout and sometimes burned with torches.[8]

Other punitive positioning devices

The term rack is also used, occasionally, for a number of simpler constructions that merely facilitate corporal punishment, after which it may be named specifically, e.g., caning rack, as in a given jurisdiction it was often the custom to administer any given punishment in a specific position, for which the device (with or without fitting shackling and/or padding) would be chosen or specially made.

Several devices similar in principle to the rack have been used through the ages. One of these was the Wooden Horse, a device used to torture prisoners during the Roman Empire by stretching them on top of a tall wooden frame until the shoulders were dislocated followed by a violent drop into a hanging position and beating. In another variant used primarily in ancient times, the victim's feet were affixed to the ground and his/her hands were chained to a wheel. When the wheel was turned, the person was stretched in a manner similar to the rack. The Austrian Ladder was basically a more vertically oriented rack. As part of the torture, victims would usually be burned under the arms with candles.

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 22 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 779–780.

- ^ Hirsch, A. E., ed., The Book of Torture and Executions, Toronto: Golden Books, 1944

- ^ Scott, G. R., A History of Torture, London: Bracken Books, 1994

- ^ The Intellectual Devotional Biographies. Rodale. 2010. ISBN 978-1594865138.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ The Anabasis of Arrian

- ^ The Annals by Tacitus (Section 15.57)

- ^ The Letters of St. Jerome, Letter I, to Innocent, ¶ 3

- ^ Котошихин Г. К. О России, в царствование Алексея Михайловича. Современное сочинение Григория Котошихина. — СПб.: Археографическая комиссия, 1859.

Sources

- Monestier, M. (1994) Peines de mort. Paris, France: Le Cherche Midi Éditeur.

- Crocker, Harry W.; Triumph: The Power and Glory of the Catholic Church - A 2,000 Year History