Blind Persons Act 1920

The Blind Persons Act 1920 is an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, since repealed. It provided a pension allowance for blind persons aged between 50 and 70 (after which they became eligible for the old age pension), directed local authorities to make provision for the welfare of blind people and regulated charities in the sector. The act was passed in response to pressure from the National League of the Blind (NLB) who claimed many of their members were living in poverty. The NLB carried out a series of strikes and protests including the 5–25 April 1920 blind march. The Blind Persons Act was first debated on 26 April and received Royal Assent on 16 August. The pensions provisions were superseded and repealed by the Old Age Pensions Act 1936 and the remainder of the act by the National Assistance Act 1948, it remains in force in Ireland. The act was the first disability-specific legislation to be passed anywhere in the world.

Background

In the early 20th century many blind people in the United Kingdom were reliant on employment by charities in workshops. This was low paid and some charities imposed strict measures, such as controlling whether their employees could marry.[1] The National League of the Blind (NLB) was founded in 1889 by Ben Purse to campaign for the rights of visually impaired persons.[2] This carried out a strike of its members in 1912 to raise awareness of their living conditions.[1][3] However, there was little improvement and by 1918 the NLB estimated that 20,000 out of the 35,000 blind people in the country were living in poverty.[1] Three times it managed to introduce legislation in parliament to address the matter but it was not passed.[4]

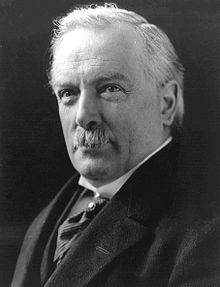

In 1918 the NLB held a large public meeting at Trafalgar Square and in 1919 disrupted a session in the House of Commons.[4] When this failed to draw a response from the government it organised the 1920 blind march, a 20-day protest march on London from across the country.[1][5] This drew public attention and, after NLB leaders met with the prime minister David Lloyd George, led directly to the Blind Persons Act 1920.[6][5]

The act

The act required local authorities to "promote the welfare of blind persons" and reduced the pension age for blind men from 70 to 50. The NLB feared that the act would simply allow local authorities to sub-contract their responsibilities to the charities that they opposed.[1] The act also ordered that blind children be permitted to take the same exams sat by sighted children and regulated the operation of charities for blind persons.[7] The estimated cost of increasing the pension provision was £175,000 per year, to be met by central government, and the capital expenditure incurred by local authorities to provide new workshops, hostels and homes was estimated at £250,000.[8] The act was first read on 26 April 1920 and received Royal Assent on 16 August.[9][10] The local authorities were granted 12 months to comply with the act.[11] The act was the first disability-specific legislation anywhere in the world.[5]

Impact

The NLB passed a motion of dissatisfaction in the government's response to the march.[1] The Royal London Society for Blind People expected that the act would not be eagerly applied by the local authorities who did not wish to increase the burden on their ratepayers.[7] Some officials in the Treasury expressed concern that the act would lead to accusations that the pension provided was not sufficient and that there would be subsequent requests from other disabled people to also have specific legislation. The treasury thought that any such schemes should come under the Poor Law, administered by local authorities.[8] Between 1921 and 1939 the number of people eligible for pensions under the act rose from 7,800 to 27,500 with a total annual cost of £695,000.[12]

As it was passed before the formation of the Irish Free State in 1922 it was retained on the statute books in that country and part of it remains in force.[13] In the United Kingdom section 1 of the act, applying to pensions, was repealed by the Old Age Pensions Act 1936, which duplicated its provisions.[14] The remaining sections were repealed by the National Assistance Act 1948.[15] Amendments and new legislation developed provision for blind, and other disabled people, throughout the 20th century. This culminated in the Disability Discrimination Act 1995, Disability Discrimination Act 2005 and the Equality Act 2010 which implemented some of the measures the NLB had first proposed in 1899.[6]

References

- ^ a b c d e f Main, Edward (30 April 2020). "'Justice not charity' – the blind marchers who made history". BBC News. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- ^ French, Sally (2017). Visual Impairment and Work: Experiences of Visually Impaired People. Taylor & Francis. p. 24. ISBN 978-1-317-17374-8.

- ^ French, Sally (2017). Visual Impairment and Work: Experiences of Visually Impaired People. Taylor & Francis. p. 25. ISBN 978-1-317-17374-8.

- ^ a b Maitland, Sara; Pester, Holly; Holness, Matthew; Cottrell-Boyce, Frank; Hedgecock, Andy; Hird, Laura; Green, Michelle; Alland, Sandra; Evers, Stuart; Waal, Kit de; Sayle, Alexei; Constantine, David; Gee, Maggie; Rhydderch, Francesca; Ross, Jacob; Quinn, Joanna; Bedford, Martyn; Jacques, Juliet; Newland, Courttia; Clanchy, Kate (2017). Protest: Stories of Resistance. Comma Press. p. 113. ISBN 978-1-905583-73-7.

- ^ a b c "Marching into history". Royal National Institute of the Blind. 3 April 2020. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- ^ a b Maitland, Sara; Pester, Holly; Holness, Matthew; Cottrell-Boyce, Frank; Hedgecock, Andy; Hird, Laura; Green, Michelle; Alland, Sandra; Evers, Stuart; Waal, Kit de; Sayle, Alexei; Constantine, David; Gee, Maggie; Rhydderch, Francesca; Ross, Jacob; Quinn, Joanna; Bedford, Martyn; Jacques, Juliet; Newland, Courttia; Clanchy, Kate (2017). Protest: Stories of Resistance. Comma Press. p. 114. ISBN 978-1-905583-73-7.

- ^ a b "1920 Blind Persons Act". Royal London Society for Blind People. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ a b Lysons, CK (1973). The development of social legislation for blind or deaf persons in England 1834–1939 (Doctor of Philosophy). Brunel Law School. p. 191-192. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ "Blind Persons Act 1920". Hansard. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ Lysons, CK (1973). The development of social legislation for blind or deaf persons in England 1834–1939 (Doctor of Philosophy). Brunel Law School. p. 195. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ Lysons, CK (1973). The development of social legislation for blind or deaf persons in England 1834–1939 (Doctor of Philosophy). Brunel Law School. p. 203. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ Lysons, CK (1973). The development of social legislation for blind or deaf persons in England 1834–1939 (Doctor of Philosophy). Brunel Law School. p. 209. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ "Blind Persons Act, 1920". Electronic Irish Statute Book (eISB).

- ^ Lysons, CK (1973). The development of social legislation for blind or deaf persons in England 1834–1939 (Doctor of Philosophy). Brunel Law School. p. 211. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ Lysons, CK (1973). The development of social legislation for blind or deaf persons in England 1834–1939 (Doctor of Philosophy). Brunel Law School. p. 599. Retrieved 7 June 2020.