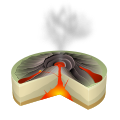

Hawaiian eruption

A Hawaiian eruption is a type of volcanic eruption where lava flows from the vent in a relatively gentle, low level eruption; it is so named because it is characteristic of Hawaiian volcanoes. Typically they are effusive eruptions, with basaltic magmas of low viscosity, low content of gases, and high temperature at the vent. Very small amounts of volcanic ash are produced. This type of eruption occurs most often at hotspot volcanoes such as Kīlauea on Hawaii's big island and in Iceland, though it can occur near subduction zones (e.g. Medicine Lake Volcano in California, United States) and rift zones. Another example of Hawaiian eruptions occurred on the island of Surtsey in Iceland from 1964 to 1967, when molten lava flowed from the crater to the sea.

Hawaiian eruptions may occur along fissure vents, such as during the eruption of Mauna Loa in 1950, or at a central vent, such as during the 1959 eruption in Kīlauea Iki Crater, which created a lava fountain 580 meters (1,900 ft) high and formed a 38-meter cone named Puʻu Puaʻi. In fissure-type eruptions, lava spurts from a fissure on the volcano's rift zone and feeds lava streams that flow downslope. In central-vent eruptions, a fountain of lava can spurt to a height of 300 meters or more (heights of 1600 meters were reported for the 1986 eruption of Mount Mihara on Izu Ōshima, Japan).

Hawaiian eruptions usually start by the formation of a crack in the ground from which a curtain of incandescent magma or several closely spaced magma fountains appear. The lava can overflow the fissure and form ʻaʻā or pāhoehoe style of flows. When such an eruption from a central cone is protracted, it can form lightly sloped shield volcanoes, for example Mauna Loa or Skjaldbreiður in Iceland.

Petrology of Hawaiian basalts

The key factors in generating a Hawaiian eruption are basaltic magma and a low percentage of dissolved water (less than one percent). The lower the water content, the more peaceful is the resulting flow. Almost all lava that comes from Hawaiian volcanoes is basalt in composition. Hawaiian basalts that make up almost all of the islands are tholeiite. These rocks are similar but not identical to those that are produced at ocean ridges. Basalt relatively richer in sodium and potassium (more alkaline) has erupted at the undersea volcano of Lōʻihi at the extreme southeastern end of the volcanic chain, and these rocks may be typical of early stages in the "evolution" of all Hawaiian islands. In the late stages of eruption of individual volcanoes, more alkaline basalt also was erupted, and in the very late stages after a period of erosion, rocks of unusual composition such as nephelinite were produced in very small amounts. These variations in magma composition have been investigated in great detail, in part to try to understand how mantle plumes may work.

Safety

Hawaiian eruptions are considered less dangerous than other types of volcanic eruptions, due to the lack of ash and the generally slow movement of lava flows. However, they can still cause injuries or deaths.

In 1993, a photographer attempting to take pictures of a lava ocean entry died, and several tourists were injured, when a lava bench collapsed. In 2000, two people were found dead near a lava ocean entry from Kīlauea, likely killed by laze.[1] Sulfur dioxide emissions can also be fatal, especially to people suffering from respiratory ailments.[1] In 2018 lava spatter from Kīlauea broke a man's leg,[2] and another 23 people on a tour boat were injured by a steam explosion at a lava ocean entry from the same eruption.[3]

See also

Notes

- ^ a b Sprowl, GM (November 2014). "Hazards of Hawai'i Volcanoes National Park". Hawai'i Journal of Medicine & Public Health : A Journal of Asia Pacific Medicine & Public Health. 73 (11 Suppl 2): 17–20. PMC 4244893. PMID 25478297.

- ^ Wang, Amy (20 May 2018). "Lava spatter hits Hawaii man and shatters his leg in first known injury from Kilauea volcano". Washington Post. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- ^ "23 Hurt After Lava From Hawaii Volcano Flies Through Roof of Tour Boat". Time. Retrieved 2018-07-17.

References

- Frankel, Charles (2005). Worlds on Fire: Volcanoes on the Earth, the Moon, Mars, Venus and Io. Cambridge University Press. pp. 21–22. ISBN 978-0-521-80393-9.

- Frankel, Charles (1996). Volcanoes of the Solar System. Cambridge University Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-521-47770-3.

- Casadevall, T.J. (ed.) (1995). Volcanic Ash and Aviation Safety: Proceedings of the First International Symposium on Volcanic Ash and Aviation Safety. DIANE Publishing. p. 437. ISBN 978-0-7881-1650-6.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)

- MacDonald, Gordon A.; Peterson, Frank L.; Abbott, Agatin T. (1983). Volcanoes in the Sea: Geology of Hawaii (2nd edition). University of Hawaii Press. pp. 156–157. ISBN 978-0-8248-0832-7.