Vinyl iodide functional group

This article focuses too much on specific examples. (December 2013) |

In organic chemistry, a vinyl iodide (also known as an iodoalkene) functional group is an alkene with one or more iodide substituents. Vinyl iodides are versatile molecules that serve as important building blocks and precursors in organic synthesis. They are commonly used in carbon-carbon forming reactions in transition-metal catalyzed cross-coupling reactions, such as Stille reaction, Heck reaction, Sonogashira coupling, and Suzuki coupling.[1] Synthesis of well-defined geometry or complexity vinyl iodide is important in stereoselective synthesis of natural products and drugs.

Properties

Vinyl iodides are generally stable under nucleophilic conditions. In SN2 reactions, back-attack is difficult because of steric clash of R groups on carbon adjacent to electrophilic center (see figure 1a).[2] In addition, the lone pair on iodide donates into the ╥* of the alkene, which reduces electrophilic character on the carbon as a result of decreased positive charge. Also, this stereoelectronic effect strengthens the C-I bond, thus making removal of the iodide difficult (see figure 1b).[3] In SN1 case, dissociation is difficult because of the strengthened C-I bond and loss of the iodide will generate an unstable carbocation(see figure 1c)[2]

In cross-coupling reactions, typically vinyl iodides react faster and under more mild conditions than vinyl chloride and vinyl bromide. The order of reactivity is based on the strength of carbon-halogen bond. C-I bond is the weakest of the halogens, the bond dissociation energies of C-I is 57.6kcal/mol, while fluoride, chloride and bromide are 115, 83.7, 72.1 kcal/mol respectively.[4] As a result of having weaker bond, vinyl iodide does not polymerize as easily as its vinyl halide counterparts, but rather decompose and release iodide.[5] It is generally believed that vinyl iodide cannot survive common reduction conditions, which reduces the vinyl iodide to an olefin or unsaturated alkane.[6] However, there is evidence in literature, in which a propargyl alcohol's alkyne was reduced in presence of a vinyl iodide using hydrogen over Pd/CaCO3 or Crabtree's catalyst.[7]

Other applications

Besides using vinyl iodides as useful substrates in transition metal cross-coupling reaction, they can also undergo elimination with a strong base to give corresponding alkyne, and they can be converted to suitable vinyl Grignard reagents. Vinyl iodides are converted to Grignard reagents by magnesium-halogen exchange (see Scheme 1a).[8] The scope of this synthetic method is limited since it requires higher temperatures and longer reaction time, which affects functional group tolerance. However, vinyl iodide with electron withdrawing group can enhance rate of exchange(see Scheme 1b).[8] Also addition of lithium chloride helps enhance magnesium-halogen exchange (see Scheme 1c). It is predicted lithium chloride breaks up aggregates in organomagnesium reagents.[9]

Methods of synthesis

Vinyl iodides are synthesized by methods such as iodination and substitution reaction. Vinyl iodides with well-defined geometry (regiochemistry and stereochemistry) are important in synthesis since many natural products and drugs that have specific structure and dimension. Example of regiochemistry is whether the iodide is positioned in either alpha or beta position on the olefin. Stereochemistry such as E-Z notation or cis-trans alkene geometry is important since some transition metal cross-coupling reactions, such as the Suzuki coupling, can retain olefin geometry. In synthesis, it is useful to introduce vinyl iodide at various positions to be set up for a coupling reaction at the next synthetic step. Below are various means and methods in introducing and synthesizing vinyl iodides.

Synthesis from alkynes

The common and simplest approach to make vinyl iodide is addition of one equivalent HI to alkyne. This generally makes 2-iodo-1-alkenes or α-vinyl iodide by Markovnikov's rule. However, this reaction does not happen at good rates or very high stereoselectively.[10] As a result, most synthetic methods often involve a hydrometalation step before addition of I+ source.

α-vinyl iodides

Introducing an α-vinyl iodide from a terminal position of an alkyne is a difficult step. in addition, the vinyl metal intermediate can be mildly nucleophilic, for example vinyl aluminum, can form C-C bonds under catalytic conditions. However, Hoveyda group have demonstrated using nickel-based catalyst (Ni(dppp)Cl2), DIBAL-H with N-iodosuccinimide (NIS), selectively favor α-vinyl iodide with little to no byproducts.[11] Also they observed reverse selectivity for β with Ni(PPh3)2Cl2 in their hydroalumination reactions under same conditions with little or no byproducts. The advantage of this method is that is inexpensive (and commercially available), scalable and one-pot reaction.

Another method doesn't involve hydrometalation but hydroiodation with I2/hydrophosphine binary system, which was developed by Ogawa's group.[12]

The hydroiodation proceeds by Markovnikov-type adduct, no reaction is observed without addition of hydrophoshine. In a plausible mechanism proposed by Ogawa's group, the hydrophosphine reacts with HI to form an intermediate complex that coordinate HI to do Markovnikov hydroiodation on the alkene. The advantage of this system is the conditions are mild, can tolerate wide range of functional groups.

β-vinyl iodides

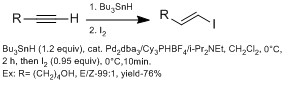

They are generally more methods in making β-vinyl iodides versus α-vinyl iodides using hydrometalation (with aluminum with DIBAL-H (hydroalumination), with boron (hydroboration), with HZrCp2Cl (hydrozirconation)).[13] However, hydrometalation with alkyne with various functional groups often react poorly with side products. The Chong groups have demonstrated using hydrostannation, using Bu3SnH with palladium catalyst with high E stereoselectivity.[13] They observed using sterically bulky ligands gave higher regioselectivity for β-vinyl iodide. The advantage of this technique is this technique can tolerate a wide range of functional groups.

Z selective β-vinyl iodides are slightly more difficult to introduce than E-β-vinyl iodides, often requiring more than one step. Hydroalumination and hydroboration usually proceed by syn fashion, therefore selectively favors E geometry. The Oshima group have demonstrated using hydroindation with HInCl selectively favors Z geometry.[14] They suggested that the reaction proceeds by a radical mechanism. They predict that HInCl adds to alkyne by radical addition in a Z geometry. It does not isomerized to E geometry because of low reactivity of radical InCl2 with intermediate complex (no second addition). If second addition occurs then isomerization will occur through diindium intermediate. They confirm a radical mechanism in a mechanistic study with alkyne and alkene cyclization.

Substitution

Substitution is perhaps most useful method in introducing vinyl iodide into the molecule. Halogen-exchange can be useful since vinyl iodides are more reactivity than other vinyl halides. Buchwald group demonstrates a halogen-exchange from vinyl bromide to vinyl iodide with copper catalyst under mild conditions.[15] It is possible that this method can tolerate various functional groups since these conditions were tested aryl halides initially. The scope of this exchange for regiochemistry and stereochemistry is currently unexplored.

Halogen-exchange can also be done with zirconium derivatives that retain olefin’s geometry[16]

The Marek group have further investigated using zirconium catalyst on E or Z vinyl ethers, which selective for E-vinyl ethers.[16] The zirconium's oxophilic nature allows elimination alkoxy group at the β position to form intermediate vinyl zirconium complex. The E geometry selectivity is not cause by sterics but rather the reaction itself is not concerted. In a mechanistic study, they observed isomerization, which suggest E geometry product is more favored than Z geometry. The difference of results between halogen exchange and E-vinyl ether reaction is that only when there is a presence of an oxonium intermediate, is isomerization observed.

An interesting substitution reaction is vinyl boronic acid to vinyl iodide done by Brown's group.[17] Depending on order of addition of iodide or base, vinyl borate can yield different stereoisomers of vinyl iodide (see scheme 2a). The Whiting group, however, noticed that Brown's method was not applicable to more sterically hindered boronic esters (no reaction).[18] They proposed that the iodide source was not electropositive enough. So they decided to use ICl which is more polar than I2, in which, they observed similar results (see scheme 2b).

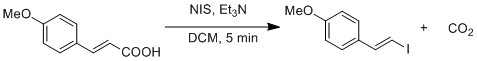

Radical substitution of carboxylic acid to iodide is demonstrated by a modified Hunsdiecker reaction.[19] Homolytic cleavage of O-I bond generates CO2 and vinyl radical. Vinyl radical recombines with iodide radical to form vinyl iodide.

Iododesilylation

Iododesilylation is a substitution reaction of silyl group for iodide. The advantages of iododesilylation are that it avoids toxic tin reagent and intermediate vinyl silyl are stable, nontoxic and easily handled and stored. Vinyl silyl can be made from terminal alkyne or other methods.

The Kishi's group reported a mild preparation of vinyl iodide from vinyl silyl using NIS in mixture of acetonitrile and chloroacetonitrile.[20] They observed retention of olefin geometry in some vinyl silyl substrates while inversion in others. They reasoned that the R group's size had an effect on the geometry of the olefin. If the R group is small, the solvent acetonitrile can participate in the reaction leading to inversion of the olefin's geometry. If the R group is big, the solvent is unable to participate, leading to retention of olefin's geometry

Zakarian's group then decided to run the reaction in HFIP, which gave high retention of olefin geometry.[21] They reasoned that HFIP is a low nucleophilicity solvent, unlike acetonitrile. In addition, they observed accelerated reaction rate because HFIP activate NIS by hydrogen bonding.

Unfortunately, iododesilylation under those conditions (above) can potentially yield multiple byproducts in highly functionalized molecules with oxygen functional groups. Vilarrasa and Costa's group hypothesized that radical reactions producing HI and I2 help facilitate cleavage in alcohol's protecting group and may add into other alkene bonds.[22] They experimented on used of silver addictive such as silver acetate and silver carbonate in which the silver can react with the excess iodide to form silver iodide. They observed no byproducts, with 100% conversion to products and increased yields.

Name reactions

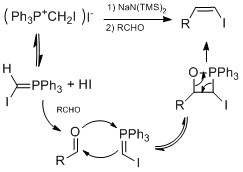

Some famous vinyl iodide synthesis methods involve conversion of aldehyde or ketone to vinyl iodide. Barton's hydrazone iodination method involves addition of hydrazines to aldehyde or ketone to form hydrazone. Then the hydrazone is converted to vinyl iodide by addition of iodide and DBU.[23][24] This method has been used in natural product synthesis of Taxol by Danishefsky[25] and Cortistatin A by Shair.[26] Another method is the Takai olefination which uses iodoform and chromium(II) chloride to make vinyl iodide from aldehyde with high stereoselectivity for E geometry.[27] For high stereoselectivity for Z geometry, Stork-Zhao olefination proceeds by Wittig-like reaction. High yields and Z stereoselectivity occurred at low temperature and at the presence of HMPA.[28]

Below is example of employing both Takai olefination and Stork-Zhao olefination in total synthesis of (+)-3-(E)- and (+)-3-(Z)-Pinnatifidenyne.[29]

Elimination method

Vinyl iodides are rarely by made an elimination reaction of vicinal diiodide because it tends to decompose to alkene and iodide.[30] The Baker group have shown using decarboxylation, elimination can occur.[31]

References

- ^ Xie, Meihua, et al. "Regio-and stereospecific synthesis of vinyl halides via carbozincation of acetylenic sulfones followed by halogenation." Journal of Organometallic Chemistry 694.14 (2009): 2258-2262.

- ^ a b Klein, David. Organic Chemistry. John Wiley & Sons, Jun 15, 2011. Google book. Thurs. 28 Nov. 2013. https://books.google.com/books?id=SsX9pbarkQkC&source=gbs_navlinks_s

- ^ Bhupinder, Mehta; Manju, Mehta. Organic Chemistry. PHI Learning Pvt. Ltd., Jan 1, 2005. Google book. Thurs. 28 Nov. 2013. https://books.google.com/books?id=QV6cwXA9XkEC&source=gbs_navlinks_s

- ^ Blanksby, Stephen J., and G. Barney Ellison. "Bond dissociation energies of organic molecules." Accounts of Chemical Research 36.4 (2003): 255-263

- ^ Herman, Jan A., and Pierre Roberge. "X‐ray induced polymerization of vinyl iodide in solution." Journal of Polymer Science 62.174 (1962): S116-S118.

- ^ Zhang, Xing, et al. "An efficient cis-reduction of alkyne to alkene in the presence of a vinyl iodide: stereoselective synthesis of the C22-C31 fragment of leiodolide A." Tetrahedron (2012).

- ^ Denton, Richard W., and Kathlyn A. Parker. "Functional Group Compatibility. Propargyl Alcohol Reduction in the Presence of a Vinyl Iodide." Organic letters 11.13 (2009): 2722-2723.

- ^ a b Rottlander, M.; Boymond, L.; Cahiez, G.; Knochel, P. J. Org. Chem. 1999. 64, 1080

- ^ Ren, H.; Krasovskiy, A.; Knochel, P. Org. Lett. 2004, 6, 4215

- ^ Kropp, P. J.; Crawford, S. D. J. Org. Chem. 1994, 59, 3102.

- ^ Gao, Fang, and Amir H. Hoveyda. "α-Selective Ni-Catalyzed Hydroalumination of Aryl-and Alkyl-Substituted Terminal Alkynes: Practical Syntheses of Internal Vinyl Aluminums, Halides, or Boronates." Journal of the American Chemical Society 132.32 (2010): 10961-10963.

- ^ Kawaguchi, Shin-ichi, and Akiya Ogawa. "Highly Selective Hydroiodation of Alkynes Using an Iodine− Hydrophosphine Binary System." Organic Letters 12.9 (2010): 1893-1895.

- ^ a b Chong, J.; Darwish, Alla. Tetrahedron, Volume 68, Issue 2, 14 Jan 2012, pages 654-658

- ^ Takami, Kazuaki, et al. "Triethylborane-mediated hydrogallation and hydroindation: Novel access to organogalliums and organoindiums." The Journal of Organic Chemistry 68.17 (2003): 6627-6631.

- ^ Klapars, Artis, and Stephen L. Buchwald. "Copper-catalyzed halogen exchange in aryl halides: An aromatic Finkelstein reaction." Journal of the American Chemical Society 124.50 (2002): 14844-14845.

- ^ a b Liard, Annie, and Ilan Marek. "Stereoselective preparation of E vinyl zirconium derivatives from E or Z enol ethers." The Journal of organic chemistry 65.21 (2000): 7218-7220.

- ^ Brown, H. C; Hamaoka, T.; and Ravindran, N.; J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1973, 95, 5786

- ^ Stewart, Sarah K., and Andrew Whiting. "Stereoselective synthesis of vinyl iodides from vinylboronate pinacol esters using ICI." Tetrahedron letters 36.22 (1995): 3929-3932.

- ^ Das, Jaya Prakash, and Sujit Roy. "Catalytic Hunsdiecker reaction of α, β-unsaturated carboxylic acids: how efficient is the catalyst?." The Journal of Organic Chemistry 67.22 (2002): 7861-7864.

- ^ Stamos, D. P.; Taylor, A. G.;Kishi, Y; Tetrahedron Lett. 1996, 37 (48), 8647-8650

- ^ Ilardi, E. A.; Stivala, C. E.; Zakarian, A., Organic Letters. 2008, 10 (9), 1727-1730

- ^ Vilarrasa, J; Sidera M; Organic Letters, 2012, 13, 4934-4937

- ^ Barton, D. H. R. , R. E. O'Brien and S. Sternhell Journal of the Chemical Society,1962, 470 - 476

- ^ Barton, D. H. R.; Bashiardes, G.; Fourrey, J.-L. Tetrahedron 1988, 44, 147

- ^ Danishefsky, Samuel J., et al. "Total synthesis of baccatin III and taxol." Journal of the American Chemical Society 118.12 (1996): 2843-2859

- ^ Lee, Hong Myung, Cristina Nieto-Oberhuber, and Matthew D. Shair. "Enantioselective synthesis of (+)-cortistatin A, a potent and selective inhibitor of endothelial cell proliferation." Journal of the American Chemical Society 130.50 (2008): 16864-16866

- ^ Simple and selective method for aldehydes (RCHO) -> (E)-haloalkenes (RCH:CHX) conversion by means of a haloform-chromous chloride system K. Takai, K. Nitta, K. Utimoto J. Am. Chem. Soc.; 1986; 108(23); 7408–7410

- ^ Stork, Gilbert, and Kang Zhao. "A stereoselective synthesis of (Z)-1-iodo-1-alkenes." Tetrahedron Letters 30.17 (1989): 2173-2174.

- ^ Kim, Hyoungsu, et al. "Construction of eight-membered ether rings by olefin geometry-dependent internal alkylation: First asymmetric total syntheses of (+)-3-(E)-and (+)-3-(Z)-pinnatifidenyne." Journal of the American Chemical Society 125.34 (2003): 10238-10240.

- ^ Ley, Steven. Synthesis: Carbon with One Heteroatom Attached by a Single Bond, Volume 2. Elsevier, 1995. Google book. Thurs. 28 Nov. 2013. https://books.google.com/books?id=BPcxrmIgLKMC

- ^ 30. Baker, Raymond, and Jose L. Castro. "Total synthesis of (+)-macbecin I." J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 1 (1990): 47-65.