Essen Minster

| Essen Minster | |

|---|---|

| The Cathedral of Our Lady, St Cosmas and St Damien | |

Essener Münster | |

Essen Minster, southern side | |

| |

| 51°27′21″N 7°00′49″E / 51.45597°N 7.01373°E | |

| Location | Essen |

| Country | Germany |

| Denomination | Roman Catholic |

| Website | Website of the Cathedral |

| History | |

| Status | Active |

| Founded | 845 |

| Dedication | 8 July 1316 |

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | Cathedral and Collegiate Church |

| Administration | |

| Diocese | Diocese of Essen |

| Clergy | |

| Bishop(s) | Franz-Josef Overbeck |

Essen Minster (German: Essener Münster), since 1958 also Essen Cathedral (Essener Dom) is the seat of the Roman Catholic Bishop of Essen, the "Diocese of the Ruhr", founded in 1958. The church, dedicated to Saints Cosmas and Damian and the Blessed Virgin Mary, stands on the Burgplatz in the centre of the city of Essen, Germany.

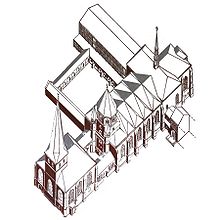

The minster was formerly the collegiate church of Essen Abbey, founded in about 845 by Altfrid, Bishop of Hildesheim, around which the city of Essen grew up. The present building, which was reconstructed after its destruction in World War II, is a Gothic hall church, built after 1275 in light-coloured sandstone. The octagonal westwork and the crypt are survivors of the Ottonian pre-Romanesque building that once stood here. The separate Church of St. Johann Baptist stands at the west end of the minster, connected to the westwork by a short atrium – it was formerly the parish church of the abbey's subjects. To the north of the minster is a cloister that once served the abbey.

Essen Minster is noted for its treasury (Domschatz), which among other treasures contains the Golden Madonna, the oldest fully sculptural figure of Mary north of the Alps.

Usage history

Foundation to 1803

From the foundation of the first church until 1803, Essen Minster was the Abbey church of Essen Abbey and the hub of abbey life. The church was neither a parish church, nor a cathedral church, but primarily served the nuns of the abbey. Its position was therefore comparable to a convent church, but a more worldly version, since the nuns at Essen did not obey the Benedictine Rule, but the Institutio sanctimonialium the canonical rule for female monastic communities, issued in 816 by the Aachen Synod. The canonical hours and masses of the order occurred in the Minster, as well as prayers for deceased members of the community, the noble sponsors of the order and their ancestors.

The number of nuns from the nobility which the church served varied over the centuries between about seventy during the order's heydey under the Abbess Mathilde in the tenth century and three in the sixteenth century. The church was open to the dependents of the order and the people of the city of Essen only on the high feast days. Otherwise the Church of St. Johann Baptist, which had developed out of the Ottonian baptistry, or the Church of St Gertrude (now the Market Church) served as their place of worship.

The Reformation had no effect on the Minster. The burgers of the city of Essen, who maintained a long-standing dispute with the order about whether the city was a Free city or belonged to the order, mostly joined the revolution, but the Abbesses and Canons of the order (and therefore the church buildings) remained Catholic. The Protestant burgers of the city took over St Gertrude's Church, the present-day Market Church, which was not connected to the Abbey's buildings, while the burgers who remained Catholic continued to use the Church of St. Johann Baptist, located in the Abbey complex, as their parish church. The nuns continued to use the Minster.

From 1803 to the present day

In 1803, Essen Abbey was mediatized by the Kingdom of Prussia. The Minster and all its property was immediately taken over by the parish community of St. Johann Baptist. For the next 150 years the church was their parish church. The name Minster church, which had become established, was retained even though the order no longer existed. As parish church, it served the Catholics of Essen's inner city area which significantly increased in population in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Though the first aspirations of setting up a bishopric of the Ruhr were dashed in the 1920s, a new bishopric was formed in 1958 from parts of the dioceses of Münster, Paderborn, and Cologne and Essen Minster was made the cathedral. On 1 January 1958 the first Bishop of Essen, Franz Hengsbach was consecrated by the Nuncio Aloisius Joseph Muench. Since then Essen Minster has been the religious heart of the diocese. The visit of Pope John Paul II in 1987 marked the high point of the Minster's thousand-year history.

Structural history

Previous buildings

The site of the cathedral was already settled before the foundation of the Abbey. The Bishop of Hildesheim, Altfrid (r.847-874) is supposed to have founded the order of nuns on his estate, called Asnide (i.e. Essen). A direct attestation of Asnide has not yet been found. But from postholes, Merovingian pottery sherds and burials found near the Minster, it can be concluded that a settlement was in place before the foundation of the Abbey.

The first church

The modern Essen Minster is the third church building on this site. Foundation walls of its predecessors were excavated in 1952 by Walter Zimmermann. The first church on this site was erected by the founders of Essen Abbey, Bishop Altfrid and Gerswid, according to tradition the first abbess of the order, between 845 and 870. The building was a three aisled basilica with a west-east orientation. Its central and side aisles already approached the width of the later churches on the site. West of the nave was a small, almost square narthex. The arms of the transeptsmet at a rectangular crossing, which was the same height as the nave. Rooms in the east ends of the side aisle were accessible only from the arms of the transepts. It is uncertain whether these rooms were the same height as the side aisles, as Zimmerman thought on the basis of his excavations or the height of the sidechoir, as in Lange's more recent reconstruction. East of the crossing was the choir with a semicircular end, with the rooms that are accessible from the transepts on either side of it.

This first church was destroyed in a fire in 946, which is recorded in the Cologne Annals Astnide cremabatur (Essen burnt down).

The early Ottonian Abbey

Several dedicatory inscriptions for parts of the new church survive from the years 960 to 964, from which it can be concluded that the fire of 946 had only damaged the church. No inscriptions survive for the nave and choir, which were probably retained from the earlier church. The individual stages of construction are uncertain; some parts could have been begun or even completed before the fire. Taking advantage of necessary renovations to expand the church enclosure was not unusual. The new parts, presumably built at the order of the abbesses Agana and Hathwig, were an outer crypt, a westwork and a narthex and an external chapel of St John the Baptist. This building can be reconstructed from archaeological finds and did not have a long existence, because a new church was erected, perhaps under the art loving Abbess Mathilde, but maybe only under Abbess Theophanu (r. 1039–1058). Possibly, a new building was begun under Mathilde and completed under Theophanu. Significant portions survive from the new Ottonian building.

The new Ottonian church

The expansion of the new Ottonian building was predetermined by its two predecessors. The greater part of the foundations were reused; only in locations where the stresses were increased or the floorplan differed were new foundations laid.

The new building also had three aisles with a transept and a choir shaped like the earlier choirs. A crypt was now built below the choir. The choir was closed with a semi-circular apse, which was encased within a half decagon. A two-story outer crypt was connected to the choir, the west walls of which formed the east walls of the side choirs. Towers next to the altar room gave direct access to the crypt. The near choirs contained matronea, which were open to the transepts and the main choir. the outer walls of the ends of the transepts were made two stories high, with the upstairs portion composed of three niches with windows. On the ground floor were niches, and the pattern of niches continued on the side walls. A walkway ran along the walls above these niches, leading to the matroneum galleries. The double bay between the westwork and the nave was maintained. The structure of the nave walls is unknown, but reconstructions based on other churches, especially Susteren Abbey which appears to draw from the new Ottonian church in many aspects, assume an interchange of piers and columns. There were probably wall paintings between the arcades and the windows on the walls, since remains of wall paintings have been found in the westwork. Outside, the clerestory of the nave had a structure of pilasters and volute capitals, probably with twelve windows.

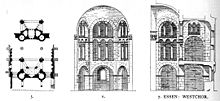

Westwork

The belief that the unknown architect of Essen Abbey church was one of the best architects of his time is based particularly on the westwork, which even today is the classic view of the church. As in the earlier churches, the westwork is only a little wider than the aisles of the nave. From the outside, the westwork appears as an almost square central tower crowned by an octagonal belfry with a pyramidal roof. At the west end there were two octagonal side towers, containing staircases to the belfry, which reached to just below the bell story of the belfry. The bell story of the central tower and the uppermost stories of the side towers have arched windows. Two story side rooms with arched windows on the upper floor are attached to the north and south sides of the central tower. On the ground floor of these side rooms, doors set in niches lead into the church – the central entrance of the earlier church was abandoned and a large, round-arched window installed in its place. With that, the westwork ceased to operate as a processional entrance to the church. Instead, the squat structure offered an optical counterpoint to the massive east part of the building.

From the outside the westwork appears to be composed of three towers, which envelop the west choir, which takes the form of a crossing which has been divided in half. No similar structure is known. There is a west choir in the central room in the shape of a half-hexagon, surrounded by a passageway. A flat niche is located in the middle of the west wall, with the entrances to the two side towers in flat niches on either side of it. The westwork opens toward the double bay through a large arch supported by pillars. An altar dedicated to Saint Peter stands in the west choir in front of this arch. The walls follow the model of the west choir of Aachen Cathedral in their construction, which also has the use of the octagon as a belfry in common. On the ground floor there are three arches divided by hexagonal pillars. There are two levels of arch openings of the upper level in colonnades, with recycled ancient capitals on the columns.

The westwork was richly decorated, with the Last Judgement painted from the half-cupola to the nave. The painting shows the appearance of Jesus to (it has been concluded) the commissioner of the painting, the Abbess Theophanu (whose name is from the Greek for Divine apparition)

Crypt

Through the installation of the crypt, the floor of the main (east) choir was raised above the floor level of the nave and transepts. The side choirs remained on the same level as the nave and transepts. The crypt consists of the three aisled crypt of Agana, an inner crypt, and a five-sided outer crypt. The entrance to the inner crypt was from east side of the side choir, through which one passed into the outer crypt. The outer crypt had square and elongated rectangular vaults, separated by delicate square pillars. The three central vaults in the east were especially accentuated. Along the east wall in the two side vaults were semicircular niches. In the central vault was a small choir with three niches. The engaged pillars of the east wall of the outer pillar have sandstone plates on which 9 September 1051 is given as the date of the crypt's consecration. There are relics in the altars of the crypt.

Later construction

A short time after the completion of the Ottonian church, the atrium was renovated, probably under Suanhild, the successor of the Abbess Theophanu. In 1471, the atrium was reduced with the renovation and expansion of the church of St. Johann Baptist, which served as the baptismal and parish church of the abbey's subjects. Otherwise the atrium probably retains the form established between 1060 and 1080.

The next extension of the church complex was an attachment to the southern transept in the twelfth century. The upper floor of this very large building contained the sectarium, where the order's papers and acts were kept and which also served as the treasury chamber. Underneath it was the open hall, which was closed at a later time and was used for judicial purposes by the court. This building is now part of the Essen Cathedral Treasury Chamber.

Gothic Hall church

In 1275, the Ottonian church burnt down, with only the westwork and the crypt surviving. In the rebuild, which occurred in the time of the Abbesses Berta von Arnsberg and Beatrix von Holte, the architect combined aspects of the old church with the new Gothic style. The form of the hall church was chosen, in complete contrast with Cologne Cathedral - the Essen order had to ward off the Archbishop of Cologne's claims to authority and the nuns wished to express their integrity and independence through the form of their building. Two architects worked alongside each other on the rebuild, of which the first, a Master Martin, quit in 1305 because of disputes with Abbess Beatrix von Holte. Master Martin, who was a church builder from Burgundy and Champagne, as shown by details of his ornamentation, also knew the design idiom of Cologne and Trier cathedral construction workshops, was responsible for the overall design. This included at first a long choir like that of St Vitus' Church, Mönchengladbach. Afterwards this concept was given up under the management of Master Martin and a hall church inspired by St. Elizabeth's Church, Marburg (begun 1235) was built, which was built over the outer crypt. The successor to Master Martin's name is not known. His design idiom is more strongly Westphalian, but he continued the plan of his predecessor and brought it to completion.

The original, shallow roofs of the octagon and the side towers were replaced with steeper caps; the side towers were also raised by a story. The Gothic church gained a tower above the crossing. The cloister was also expanded. The whole new building was consecrated on the 8th of July, probably of 1316. The 8th of July is celebrated to this day as the Minster's anniversary.

Later alterations

In the eighteenth century, the church was baroquified. The tower over the crossing was replaced with a narrow flèche. The windows of the south side of the cathedral were widened and lost their gothic tracery. The steep roofs of the westwork were replaced with baroque onion domes and the bell story received a clock. In the interior a large part of the old interior decoration was removed and replaced, so that only a few pieces of the gothic decoration have survived, which are no longer in their proper context.

In 1880 the fashionable view of the gothic as the uniquely German architectural style reached Essen and the baroque additions were undone, as far as possible. The westwork returned to its previous appearance, when Essen architect and art historian Georg Humann was able to effect its gothicisation. The baroque interior decoration was also removed; a side altar is now employed as the high altar of the adoration church of St. Johann Baptist in front of the Minster. Some saint statues are found there, others in the Cathedral Treasury Chamber. The decoration made to replace the baroque pieces fell victim to the Second World War, so that little of it now survives. During the renovation of 1880 the church also received its current roofing design and a neo-gothic flèche on the crossing.

War damage and rebuilding

On the night of the 5th and 6 March 1943, 442 aircraft of the Royal Air Force carried out a raid on the city of Essen, which was important to the German war effort because of the Krupp steel works. In less than an hour, 137,000 incendiary bombs and 1,100 explosive bombs were dropped on the central city. The Minster caught fire and suffered heavy damage – the oldest parts of the building, the westwork and the crypt were less heavily damaged. The decision to rebuild was made unanimously in the first meeting of the city council organised by them after the city's occupation by allied troops, under the communist mayor Heinz Renner. The war damage also enabled extensive archaeological excavations to be carried out in the church by Walter Zimmermann. These provided a large amount of information about the predecessors of the modern church and about the burials in the church.

The rebuilding was begun in 1951 and proceeded apace. By 1952 the westwerk and the nave were usable once more and the rest of the church was rebuilt by 1958. Even the northside of the cloisters, which had collapsed in the nineteenth century, was repaired. The neo-gothic flèche from the previous century was replaced by a narrower, lightning-proof flèche, completing the modern external appearance of the church. The completely repaired church became the seat of the newly founded Diocese of Essen in 1958.

Recent changes

The abbey never grew beyond the limits of the Ottonian church. The transformation into a cathedral made a new expansion necessary. Cardinal Franz Hengsbach, the first bishop, said during his lifetime that he wished to make use of his right to be buried within his cathedral church, but not in the Ottonian crypt with Saint Altfrid. In order to fulfill this wish, a west crypt with an entrance in the old westwerk was installed under the atrium between 1981 and 1983 by the cathedral architect Heinz Bohmen and decorated with cast concrete sculpture by Emil Wachter. In this Adveniat crypt, whose name reflects the fact that Cardinal Hengsbach was a co-founder of the episcopal charity Bischöfliche Aktion Adveniat, the remains of a canon who had been buried in the atrium in the Middle Ages and discovered during the excavations was buried and in 1991 the cardinal was interred there as well.

On 10 October 2004, the newly built south side chapel was dedicated to the memory and veneration of Nikolaus Groß, who was beatified in 2001.

Measurements

The whole church, together with the church of St. Johann Baptist on the front is 90 metres long. Its width varies between 24 and 31 metres at the transepts at the start of the Cathedral treasury. The height varies also:

| Section | Interior height | Exterior height |

|---|---|---|

| Nave | 13 m (vaults) | 17 m |

| Choir (with crypt) | 15 m (vaults) | 20 m |

| Westwork | 35 m | |

| Crossing tower | 38 m | |

| Tower of St. Johann's | 50 m |

The volume of the Minster is roughly 45,000 m³, volume of the masonry is about 10,000 m³. The building weighs roughly 25,000 tonnes.

Fittings

As a result of the baroquification of the eighteenth century, the re-gothificisation of the nineteenth century and the war damage of the twentieth century, there are only a few pieces of the earlier fittings of the Minster, but some remains of great significance do survive. The interior is comparatively simple, especially in its architecture, whose subtle beauty is overlooked by many visitors because the lustre of the two very important medieval artworks of the Cathedral outshines it.

Cathedral Treasury

The Minster possesses a Cathedral Treasury, which is open to the public. The most important treasure of the church, the Golden Madonna, has been found in the northern side chapel since 1959. This is the oldest fully sculptured statue of Mary, the patron saint of the diocese, in the world. The 74 cm high figure of gilded poplar, dates from the period of the abbess Mathilde and depicts Mary as a heavenly queen, holding power over the Earth on behalf of her son. The figure, which was originally carried in processions, was probably placed in Essen because of Mathilde's relationship to the Ottonian dynasty. The figure, which is more than a thousand years old, was comprehensively restored in 2004.

In the centre of the westwork the monumental Seven-arm candelabrum now stands, which the Abbess Mathilde had made between 973 and 1011. The candelabrum, 2.26 metres high with a span of 1.88 metres is composed of 46 individual cast bronze pieces. The candelabrum symbolises the unity of the Trinity and the Earth with its four cardinal points and the idea of Christ as the light of the World, which will lead the believers home at the Last Judgement (Book of Revelation).

Other remarkable items in the Cathedral treasury include the so-called Childhood Crown of Otto III, four Ottonian processional crosses, the long-revered Sword of Saints Cosmas and Damian, the cover of the Theophanu Gospels, several gothic arm-reliquaries, the largest surviving collection of Burgundian fibulae in the world and the Great Carolingian Gospels.

Column of Ida

The oldest surviving fitting in the Minster is the column in the choir, which now supports a modern crucifix. Until the fifteenth century it supported a cross coated with a gilt copper sheet, from which the donation plate and probably other remains in the Cathedral treasury were made. The Latin inscription ISTAM CRUCEM (I)DA ABBATISSA FIERI IUSSIT (Abbess Ida ordered this cross to be made) allows the creator to be identified with the Essen Abbess Ida, who died in 971, though the sister of Abbess Theophanu, Ida, Abbess of St. Maria im Kapitol in Cologne has also been suggested. The column itself is probably ancient spolia, going by fluted pedestal and the Attic basis of the column. The capital was carved in antiquity, though exceptionally richly carved for that period. Stylistically it is related to the capitals of the west end and the crypt, as well as those of the Ludgeridan crypt of Werden Abbey and those of St Lucius' Church in Essen-Werden.

Altfrid's grave monument

In the east crypt there is a limestone gothic church monument of the Bishop of Hildesheim and founder of Essen, Altfrid, which dates to around 1300 and was probably built under Abbess Beatrix von Holte. This dating is based on the striking similarity of the tomb to saints' graves at Cologne, especially the grave of St. Irmgard in Cologne Cathedral.

Further artworks

The sandstone sculptural group, called the "Entombment of Christ" (Grablegung Christi) in the southern side chapel is from the late Gothic period. The unknown Cologne Master who created it in the first quartre of the sixteenth century is known by the notname Master of the Carben Monument. Another sculpture from the early sixteenth century is the sculpture of the Holy Helper, Saint Roch on the north wall of the Minster, created shortly after 1500.

The baroque period is represented in Essen Minster by two epitaphs. The older, for Abbess Elisabeth von Bergh-s’Heerenberg who died in 1614, contains significant Renaissance elements. This plaque made of black marble in Antwerp is found on the north wall, east of the side bay and shows the Abbess in her official outfit, surrounded by the coats of arms of her ancestors. The second epitaph is that of the Abbess Anna Salome von Salm-Reifferscheidt, which is attributed to Johann Mauritz Gröninger and is found on the north wall of the organ loft.

Because of the war damage, the Minster has no medieval windows. But among the modern artworks Essen Cathedral Chapter commissioned during the rebuild, were new windows for the church and modern sacral art, which was to be in harmony with the older elements of the building. The window of St Michael and the windows of the gallery are by Heinrich Campendonk, the choir windows by Ludwig Gies, those of the nave by Wilhelm Buschulte and the windows of the crypt are by Alfred Manessier. The altar frieze is the work of sculptor Elmar Hillebrand and his student Ronald Hughes. The bronze doors of the atrium and church as well as the frieze depicting the stations of the cross in the nave are the work of the Austrian artist Toni Schneider-Manzell.

Organ

The minster's new organ was inaugurated in 2004. It was built by the renowned organbuilder Rieger of Schwarzach, which was founded by Franz Rieger. The instrument consists of two organs, and has 69 stops altogether (5,102 pipes, 95 organ stops).

The main instrument is located in the choir loft. It has 57 stops in 3 manual divisions and a pedal division,[1] and it has a fourth manual on which the auxiliary organ can be played.

The auxiliary organ is located in the west part of the cathedral. It has three manual divisions with ten stops and a pedal division with two stops, and has a significant role in producing sound in the rear region of the Cathedral. Its high pressure and bombard stops are for special solo effects. The three manual divisions can be played on the fourth manual of the main console, and each can also be coupled separately to its other manuals.[2]

Bells

There are bells in the belfry of the westwork and also in the flèche over the crossing. The ringing of the Minster is expanded tonally by the ringing of the attached church of St. Johann Baptist, whose bells, cast in 1787, are not tonally matched to the somewhat older bells of the Minster, so that when they ring together there is a slight musical impurity.

There are three large bells in the westwork. The oldest bell was already in place at the end of the thirteenth century. It bears the inscription CHRISTUM DE LIGNO CLAMANTEM DUM SONO SIGNO (When I sound, I signal that Christ calls from the cross). By its construction it is an early gothic three chime bell. The Marybell is the largest of the bells. It bears a longer inscription saying that it was cast in 1546. The bell was cast in Essen itself, in the modern Burgplatz. The third bell in the westwork lacks an inscription, but its shape marks it as fourteenth century.

The flèche holds three more bells, two of which were cast in 1955 by the bell founders Petit & Gebr. Edelbrock of Gescher, who thereby brought their foundry back to the bell making tradition, since their foundry had cast the bells of St. Johann Baptist in 1787. These two bells are inscribed Ave Maria Trösterin 1955 (Hail Mary, Counselor, 1955) and Ave Maria Königin 1955 (Hail Mary, Queen, 1955). The third bell in the flèche bears the inscription WEI GOT WEL DEINEN DEI BIDDE VOR DE KRESTEN SEELEN AN 1522 (He who serves God well prays for the Christian souls, Y(ear) of O(ur Lord) 1522).

| # |

Name |

Date |

Casters & Foundry |

Diameter (mm) |

Weight (kg, ca.) |

Strike tone (ST-1/16) |

Tower |

| 1 | Mary | 1546 | Derich von Coellen (ascribed) | 1389 | 1650 | e1 –4 | Westwork |

| 2 | Christ ("Dumsone") | End of the 13th century | Unknown | 1278 | 1200 | fis1 –1 | Westwork |

| 3 | – | 14th century | Unknown | 917 | 450 | ais1 +5 | Westwork |

| 4 | – | 1522 | Unknown | 477 | 80 | gis2 +4 | Flèche |

| 5 | Mary the Counselor | 1955 | Petit & Gebr. Edelbrock, Gescher | 425 | 50 | ais2 +3 | Flèche |

| 6 | Mary the Queen | 1955 | Petit & Gebr. Edelbrock, Gescher | 371 | 38 | cis3 +3 | Flèche |

| I | John the Baptist | 1787 | Henricus & Everhardus Petit, Aarle-Rixtel | 995 | 680 | gis1 +1 | Bell tower of St. Johann's |

| II | John the Evangelist | 1787 | Henricus & Everhardus Petit, Aarle-Rixtel | 790 | 330 | his1 –4 | Bell tower of St. Johann's |

| III | Johannes Baptist | 1787 | Henricus & Everhardus Petit, Aarle-Rixtel | 669 | 200 | dis2 –1 | Bell tower of St. Johann's |

Cathedral chapter

Essen Cathedral chapter includes six resident and four non-resident Cathedral capitular vicars under the oversight of the Cathedral provost. At present two of the resident positions are vacant and one of the non-resident positions.

Under the Concordat of 1929 the right to elect the bishop was given to the chapter, alongside their existing duties concerned with liturgical celebrations in the high church, selection of a Diocesan administrator, advising and supporting the bishop in the government of the diocese and management of the Cathedral Treasury.

Since 2005, the Cathedral provost has been the civic dean of Essen, Prelate Otmar Vieth, as successor of Günter Berghaus who went into retirement after heading the Cathedral chapter for eleven years from 1993 to 2004.

References

Notes

- ^ Information on the main organ on the website of the Cathedral music department (German)

- ^ Information on the Auxiliary organ on the website of the Cathedral music department (German)

- ^ Gerhard Hoffs: Glockenmusik der kath. Kirchen im Stadtdekanat Essen. pp. 46–48 Archived 2013-09-25 at the Wayback Machine (PDF; 1,5 MB, German)

Sources

- Leonhard Küppers: Das Essener Münster. Fredebeul & Koenen, Essen 1963.

- Klaus Lange: Der gotische Neubau der Essener Stiftskirche, in: Reform – Reformation -Säkularisation. Frauenstifte in Krisenzeiten. Klartext Verlag Essen 2004

- Klaus Lange: Die Krypta der Essener Stiftskirche. in: Essen und die sächsischen Frauenstifte im Frühmittelalter. Klartext Verlag, Essen 2003, ISBN 3-89861-238-4.

- Klaus Lange: Der Westbau des Essener Doms. Architektur und Herrschaft in ottonischer Zeit, Aschendorffsche Verlagsbuchhandlung, Münster 2001, ISBN 3-402-06248-8.

- Albert Rinken: Die Glocken des Münsters und der Anbetungskirche in: Münster am Hellweg 1949, S. 95ff.

- Josef Schueben: Das Geläut der Münsterkirche in: Münster am Hellweg 1956, S. 16ff.

- Walter Zimmermann: Das Münster zu Essen. Düsseldorf 1956.

External links

- Essen Cathedral website (in German)

- Diocese of Essen website (in German)

- Münsterbauverein website (in German)