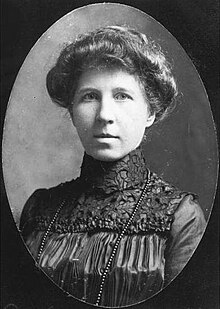

Annie Lowrie Alexander

Annie Lowrie Alexander | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | January 10, 1864 |

| Died | October 15, 1929 (aged 65) |

| Resting place | Elmwood Cemetery 35°14′16.08″N 80°50′53.16″W / 35.2378000°N 80.8481000°W |

| Alma mater | Woman's Medical College of Pennsylvania |

| Occupations |

|

| Known for | First licensed female physician in the Southern United States |

Annie Lowrie Alexander (January 10, 1864 – October 15, 1929) was an American physician and educator. She was the first licensed female physician in the Southern United States.[1]

Biography

Alexander was born on January 10, 1864, near the town of Cornelius in Mecklenburg County, North Carolina. She was one of six children of John Brevard Alexander and Ann Wall Lowrie, descended from the Reverend Alexander Craighead and the Reverend David Caldwell.[2]

She was heavily influenced by her father, also a doctor, to pursue the medical field after one of his female patients refused medical attention because he was male and as a result, died.[3]

She was educated by a private tutor and her father and enrolled in the Woman's Medical College of Pennsylvania. She graduated with honors in 1884 and obtained her license to practice medicine from the Maryland Board of Medical Examiners the next year, earning the highest grade among 100 candidates.[2] She started her own practice and was an assistant teacher of anatomy at the Women's Medical College of Baltimore. She returned to Mecklenburg County in 1887 to practice medicine[4] and in 1889 she bought a home in Charlotte, North Carolina. She slowly built up her practice, making her rounds on a horse-drawn buggy until she purchased an automobile in 1911.[2]

Alexander did postgraduate work at New York Polyclinic. Being a rarity, female physicians were not generally accepted in the late 1800s. Her work so shocked some of her relatives that they asked that her name not be mentioned in their presence.[5]

For twenty-three years she was a physician for the Presbyterian College for Women (now known as Queens University of Charlotte).[6] During Alexander's time in Charlotte, there were outbreaks of malaria and typhoid fever as well as a hookworm epidemic.[2]

Alexander was a first lieutenant in the Army during World War I[1] and was appointed acting assistant surgeon at Camp Greene in Charlotte, where she performed medical inspections of the school children and grappled with the devastation wrought by the 1918 flu pandemic.[7]

She served as president of the Mecklenburg Medical Society and was a member of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, the Charlotte Woman's Club, and the Daughters of the American Revolution.[2]

Alexander died on October 15, 1929, in Charlotte of pneumonia contracted from a patient.[2]

Further reading

- Annie L. Alexander Papers, J. Murrey Atkins Library, UNC Charlotte

References

- ^ a b Goodpasture, Joe (November 2007). "Call Her Doctor: The South's first female physician was a true pioneer". Charlotte Magazine.

- ^ a b c d e f Cohn, Scotti (2012). More Than Petticoats: Remarkable North Carolina Women. Globe Pequot. pp. 82–92. ISBN 978-0-7627-6445-7.

- ^ http://northcarolinahistory.org/encyclopedia/annie-lowrie-alexander-1864-1929/

- ^ Censer, Jane Turner (2003). The Reconstruction of White Southern Womanhood, 1865-1895. Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press. p. 155. ISBN 978-0-8071-2921-0.

- ^ Steelman, Ben (June 20, 1999). "Book packed full of 'History'". Star-News.

- ^ Kratt, Mary Norton (1992). "Is There A Doctor?". Charlotte, Spirit of the New South. John F. Blair. p. 160. ISBN 978-0-89587-095-7.

- ^ Powell, William S. (ed.) (1988). Dictionary of North Carolina Biography: Vol. 1, A-C. Chapel Hill u.a.: Univ. of North Carolina Pr. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-8078-1329-4.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)

- 1864 births

- 1929 deaths

- People from Charlotte, North Carolina

- People from Cornelius, North Carolina

- Drexel University alumni

- Physicians from North Carolina

- Woman's Medical College of Pennsylvania alumni

- 19th-century American women physicians

- 19th-century American physicians

- Daughters of the American Revolution people

- Deaths from pneumonia

- Members of the United Daughters of the Confederacy