Gert Adendorff

Gert Wilhelm Adendorff (10 July 1848 – c. 1914) was a member of the Natal Native Contingent notable for being the only soldier on the British side present at both the Battle of Isandlwana and the Battle of Rorke's Drift during the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879 made memorable in the film Zulu (1964).[1][2]

Adendorff's grandfather Michiel Joseph Adendorff was a German surgeon who had been on his way from Europe to the Far East but on disembarking at the Cape with a case of fever had decided to stay. Here his son Michiel Joseph Adendorff (1799-) was born[2] who with his French wife had 13 children: Michiel Joseph; August Rouverie Adendorff, who later served as a Captain in the Abalondolozi Regiment in the Transkei c.1880-1881; Jeremie August; Jan; Edward Christiaan; Christiaan Hendrik; Frederik Barend; Frans Louis; Gert Wilhelm; Joseph Johannes, Louis Danel, and George Frederick Adendorff.

Gert Adendorff was born in 1848 in Graaff-Reinet in the Eastern Cape. He volunteered to join the Kaffrarian Rifles, an Irregular unit formed from amongst the German-speaking settlers of the Cape frontier during the 9th Frontier War against the amaXhosa. At the conclusion of that campaign and the likelihood that a new one would commence in Zululand he volunteered and joined the 3rd Regiment of the Natal Native Contingent as a Lieutenant. With that rank he served at Isandlwana where he was in the camp on the morning of the Battle of Isandlwana on 22 January 1879, [1] serving with No. 6 Company NNC under Captain Krohn and Lieutenant Higginson.[3][4]

Escape from Isandlwana

On the morning of the Battle of Isandlwana Adendorff brought reports in to the Camp from the outlying Natal Native Contingent pickets on the iNyoni Ridge. During the battle Adendorff’s company was held in reserve formed up in front of the Camp where Adendorff remained with his men until they broke and fled during the final ferocious and determined Zulu attack. He and the other officers of the NNC, realising that the battle was lost, fled with them. Lieutenant Higginson of the NNC in his report recorded that:

Capt. Krohn, Lieut. Ordendorf [sic] and myself had been firing for some time on the right of our companies tents, and when we saw the soldiers retreating we went for our horses which we had fastened close to us to be ready for any emergency.[4][5]

When his horse was killed under him as he rode down into the Manzimnyama Valley he commandeered another at gunpoint from a mounted auxiliary and escaped from the battlefield with inkosi Hlubi's mounted Sotho troop. Breaking through the 'right horn' of the Zulu attack they followed the Buffalo River upstream where many were caught and killed by the fast-moving Zulu warriors pursuing them. The survivors including Adendorff stopped and rested their horses on the ground just below Rorke's Drift.[1][4]

Rorke's Drift

Adendorff and another soldier named Vane who had escaped from Isandlwana with him rode up to Rorke's Drift to warn the garrison there of an imminent attack. They arrived at about 3.15 pm on the Zulu side of the Buffalo River while Lieutenant John Chard was in his tent by the ponts on the other side.[6] They called out to be taken across the river.[7] In his report Chard wrote:

My attention was called to two horsemen galloping towards us from the direction of Isandlwana. From their gesticulations and their shouts, when they were near enough to be heard, we saw that something was the matter, and on taking them over the river, one of them, Lieut. Adendorff of Lonsdale's Regiment, Natal Native Contingent, asking if I was an officer, jumped off his horse, took me on one side, and told me the camp was in the hands of the Zulus and the army destroyed; that scarcely a man had got away to tell the tale, and that probably Lord Chelmsford and the rest of the column had shared the same fate. His companion, a Carbineer, confirmed his story.[4][8][9]

In 1883 Adendorff spoke with Walter Stafford about what happened that day, with Stafford recording:

A friend of mine, Lieut. Odendorff, and another man, as both could not swim, hugged the bed of the river up to the punt and were ferried across the river. It was them who gave the alarm at Rorke's Drift[10]

In his official report of the Battle of Rorke's Drift Chard stated that Adendorff was the only survivor from Isandlwana who stayed to assist with the defence at Rorke's Drift, taking up position inside the storehouse and remaining there throughout the battle.[1] Private Henry Hook later stated:

One of the horsemen was Lieutenant Adendorff and the other was a Natal Carbineer. The lieutenant stayed behind with us, and the Carbineer, who was in his shirt-sleeves, dashed on to Helpmakaar, twelve miles away to take the news there.[4]

As the mission station at Rorke's Drift was being fortified ready for the imminent attack the soldier who had arrived with Adendorff was sent to Helpmekaar to warn them of what was happening. Chard later stated that Adendorff called out he would stay and help with the defence of the mission station. In his letter to Queen Victoria describing the battle Chard added:

As far as I know, but one of the fugitives remained with us - Lieut. Adendorff, whom I have before mentioned. He remained to assist in the defence, and from a loophole in the store building, flanking the wall and Hospital, his rifle did good service.[4][8]

Chard in his two reports on the battle stated that he believed Adendorff was among the defenders at Rorke’s Drift. Further testimony that Adendorff was among those fighting in the storehouse was provided by Trooper Symons of the Natal Carbineers who, while not present at the battle himself, spoke to some who were. Symons wrote:

When the hospital was fired by the Zulus, the men at once set to work to pull off the thatch from the dwelling house. A German or some foreigner who was with the garrison saved that building from fire for he saw a Zulu with a lighted bunch of grass just raising it up to the eaves and promptly shot him.[11]

This is clearly a description of Adendorff who was the only man speaking a foreign language at Rorke’s Drift apart from Corporal Schiess who was fighting on the barricades before he was injured.[4]

Aftermath

In the weeks after the Battle of Isandlwana Henry Charles Harford, an officer of the Natal Native Contingent, wrote an Almanac which included details of the officers and men of the NNC who had deserted, including Captain Stephenson, and those who had fought at Rorke’s Drift, which included Adendorff. Hartford included details of Adendorff’s next of kin and where they lived, implying that Harford had spoken to Adendorff and believed he was among the defenders.[12] Harford also drew a sketch of Adendorff at Rorke’s Drift with some of his men when the NNC was disbanded and the Natives were handing in their weapons and equipment.

Trooper Symons of the Natal Carbineers was among those with Lord Chelmsford’s relief column recorded that Adendorff was present that morning.[11] Adendorrf took little part in the rest of the Anglo-Zulu War and left the military when the 3rd Regiment of the Natal Native Contingent was disbanded as a result of their failure at Isandlwana.[2]

By 1882 Adendorff was a Clerk working for the Gold Commission and living in the Newcastle area of northern Natal. Later he moved to the Transvaal where he married Hester Grobler, a widow.[2] During the Boer War Adendorff 'surrendered' when the British forces occupied Elandsfontein in January 1901. The War caused him financial loss, and writing from his home in Pretoria he later claimed for the loss of a 'Scotch cart' taken by the British after his surrender as well as for a horse and two mules taken by the Transvaal Government in February and May 1900. Adendorff was then employed as "Responsible Clerk and JP" at the Charges Office in Elandsfontein.

Gert Adendorff died in about 1914.[2]

In the film Zulu which depicts the Battle of Rorke's Drift Adendorff was portrayed by Gert van den Bergh.

Controversy

The author Donald Morris in his The Washing of the Spears made the unverified claim that Adendorff was not present at Rorke's Drift, saying that he fled early in the battle in the same way he had fled Isandlwana. Morris imputes cowardice to Adendorff, saying he must have left Isandlwana earlier than he claimed to have arrived at Rorke's Drift by 3.15 pm, and that as the other survivors of the Natal Native Contingent fled with the approach of the Zulus so too must have Adendorff. The imputation of cowardice to Adendorff is unfair as he was a volunteer while professional soldiers such as Horace Smith-Dorrien and others thought the best option was to escape from Isandlwana and head for Helpmekaar and remain with their reputations unblemished.[6]

However, Adendorff clearly was present throughout the battle as verified by several important witnesses including Lt. John Chard VC,[8] Private Henry Hook VC and Adendorff's own account of his involvement in the battle which can be independently verified.[1] The fact that he was a stranger and was in the storehouse throughout the battle accounts for his relative invisibility.[2]

The war correspondent Charles Norris-Newman was among Lord Chelmsford’s relief column that entered Rorke's Drift the morning after the battle and recorded:

The following officers were also present at the post and rendered material aid in the defence: Dr. Reynolds, 1-24th, Lieutenant Adendorff 1-3rd NCC, Messrs. Dunne, and Dalton, of the Commissariat Department, also the Rev. Mr. Smith, Protestant Chaplain to No 3 Column.[13]

References

- ^ a b c d e Ian Knight, Companion to the Anglo-Zulu War, Pen & Sword Militay (2008) - Google Books

- ^ a b c d e f Adrian Greaves and Ian Knight, Who's Who in the Anglo Zulu War, 1879: The Colonials and The Zulus, Lamorna Publishing Services (2006) - Google Books

- ^ Higginson - WO 33/34 56333 - National Archives

- ^ a b c d e f g Sam Stopps, Lieut. Adendorff – Rorke’s Drift Defender – Fact or Fiction? - Anglo Zulu War Historical Society

- ^ Higginson, “A report to Lord Chelmsford dated 17th of February 1879.”

- ^ a b Adrian Greaves, Rorke's Drift, W&N (2003) - Google Books

- ^ Frances Ellen Colenso, History of the Zulu War and Its Origin, Havertown, Pa. (2009) - Google Books

- ^ a b c John Chard, letter to Queen Victoria, 21 February 1880, quoted in Norman Holme, The Noble 24th: Biographical Records of the 24th Regiment in the Zulu and South African Campaigns 1877-1879, Savannah Publications (1999)

- ^ Neil Thornton, Rorke's Drift: A New Perspective, Fonthill Media (2016) - Google Books

- ^ The Mysterious Lieutenant Adendorff of Rorke's Drift; Hero or Coward? By Ian Knight AZWHS

- ^ a b 'My Reminiscences of the Zulu War' by J.P. (Fred) Symons - unpublished typescript (N.D.) - Campbell Collections, University of Natal

- ^ Payne, David and Emma, Henry Charles Harford - ‘The Beetle Collector’ Hero of the Zulu War, Soldier and Entomologist, The Ultimatum Tree Limited (2008)

- ^ Charles Norris-Newman, In Zululand with the British Army, Oakpast (2006)

Notes

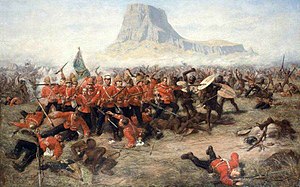

- ^ Lieutenants John Chard and Gonville Bromhead (centre) commanding, behind them Padre George Smith hands out ammunition, Private Frederick Hitch (right, standing) handing out ammunition while wounded; Surgeon James Henry Reynolds and Storekeeper Byrne tending to the wounded Corporal Scammell (Reynolds kneeling; Byrne falling, shot). Possibly Corporal Ferdinand Schiess at centre background at the barricade, left of Chard and Bromhead, face not shown.