Electron scattering

| Electron Scattering | |

|---|---|

Pictorial description of how an electron beam may interact with a sample with nucleus N, and electron cloud of electron shells K,L,M. Showing transmitted electrons and elastic/inelastic-ally scattered electrons. SE is a Secondary Electron ejected by the beam electron, emitting a characteristic photon (X-Ray) γ. BSE is a Back-Scattered Electron, an electron which is scattered backwards instead of being transmitted through the sample. | |

| Electron ( e− , β− ) | |

| Particle | Electron |

| Mass | 9.10938291(40)×10−31 kg[1] 5.4857990946(22)×10−4 u[1] [1822.8884845(14)]−1 u[note 1] 0.510998928(11) MeV/c2[1] |

| Electric Charge | −1 e[note 2] −1.602176565(35)×10−19 C[1] −4.80320451(10)×10−10 esu |

| Magnetic Moment | −1.00115965218076(27) μB[1] |

| Spin | 1⁄2 |

| Scattering | |

| Forces/Effects | Lorentz force, Electrostatic force, Gravitation, Weak interaction |

| Measures | Charge, Current |

| Categories | Elastic collision, Inelastic collision, High energy, Low energy |

| Interactions | e− — e− e− — γ e− — e+ e− — p e− — n e− — Nuclei |

| Types | Compton scattering Møller scattering Mott scattering Bhabha scattering Bremsstrahlung Deep inelastic scattering Synchrotron emission Thomson scattering |

Electron scattering occurs when electrons are deviated from their original trajectory. This is due to the electrostatic forces within matter interaction or,[2][3] if an external magnetic field is present, the electron may be deflected by the Lorentz force.[citation needed][4][5] This scattering typically happens with solids such as metals, semiconductors and insulators;[6] and is a limiting factor in integrated circuits and transistors.[2]

The application of electron scattering is such that it can be used as a high resolution microscope for hadronic systems, that allows the measurement of the distribution of charges for nucleons and nuclear structure.[7][8] The scattering of electrons has allowed us to understand that protons and neutrons are made up of the smaller elementary subatomic particles called quarks.[2]

Electrons may be scattered through a solid in several ways:

- Not at all: no electron scattering occurs at all and the beam passes straight through.

- Single scattering: when an electron is scattered just once.

- Plural scattering: when electron(s) scatter several times.

- Multiple scattering: when electron(s) scatter very many times over.

The likelihood of an electron scattering and the degree of the scattering is a probability function of the specimen thickness to the mean free path.[6]

History

The principle of the electron was first theorised in the period of 1838-1851 by a natural philosopher by the name of Richard Laming who speculated the existence of sub-atomic, unit charged particles; he also pictured the atom as being an 'electrosphere' of concentric shells of electrical particles surrounding a material core.[9][note 3]

It is generally accepted that J. J. Thomson first discovered the electron in 1897, although other notable members in the development in charged particle theory are George Johnstone Stoney (who coined the term "electron"), Emil Wiechert (who was first to publish his independent discovery of the electron), Walter Kaufmann, Pieter Zeeman and Hendrik Lorentz.[10]

Compton scattering was first observed at Washington University in 1923 by Arthur Compton who earned the 1927 Nobel Prize in Physics for the discovery; his graduate student Y. H. Woo who further verified the results is also of mention. Compton scattering is usually cited in reference to the interaction involving the electrons of an atom, however nuclear Compton scattering does exist.[citation needed]

The first electron diffraction experiment was conducted in 1927 by Clinton Davisson and Lester Germer using what would come to be a prototype for modern LEED system.[11] The experiment was able to demonstrate the wave-like properties of electrons,[note 4] thus confirming the de Broglie hypothesis that matter particles have a wave-like nature.[citation needed] However, after this the interest in LEED diminished in favour of High-energy electron diffraction until the early 1960s when an interest in LEED was revived; of notable mention during this period is H. E. Farnsworth who continued to develop LEED techniques.[11]

High energy electron-electron colliding beam history begins in 1956 when K. O'Neill of Princeton University became interested in high energy collisions, and introduced the idea of accelerator(s) injecting into storage ring(s). While the idea of beam-beam collisions had been around since approximately the 1920s, it was not until 1953 that a German patent for colliding beam apparatus was obtained by Rolf Widerøe.[12]

Phenomena

Electrons can be scattered by other charged particles through the electrostatic Coulomb forces. Furthermore, if a magnetic field is present, a traveling electron will be deflected by the Lorentz force. An extremely accurate description of all electron scattering, including quantum and relativistic aspects, is given by the theory of quantum electrodynamics.

Lorentz force

The Lorentz force, named after Dutch physicist Hendrik Lorentz, for a charged particle q is given (in SI units) by the equation:[13]

where qE describes the electric force due to a present electric field,E, acting on q.

And qv x B describes the magnetic force due to a present magnetic field, B, acting on q when q is moving with velocity v.[13][14]

Which can also be written as:

where is the electric potential, and A is the magnetic vector potential.[15]

It was Oliver Heaviside who is attributed in 1885 and 1889 to first deriving the correct expression for the Lorentz force of qv x B.[16] Hendrik Lorentz derived and refined the concept in 1892 and gave it his name,[17] incorporating forces due to electric fields.

Rewriting this as the equation of motion for a free particle of charge q mass m,this becomes:[13]

or

in the relativistic case using Lorentz contraction where γ is:[18]

this equation of motion was first verified in 1897 in J. J. Thomson's experiment investigating cathode rays which confirmed, through bending of the rays in a magnetic field, that these rays were a stream of charged particles now known as electrons.[10][13]

Variations on this basic formula describe the magnetic force on a current-carrying wire (sometimes called Laplace force), the electromotive force in a wire loop moving through a magnetic field (an aspect of Faraday's law of induction), and the force on a particle which might be traveling near the speed of light (relativistic form of the Lorentz force).

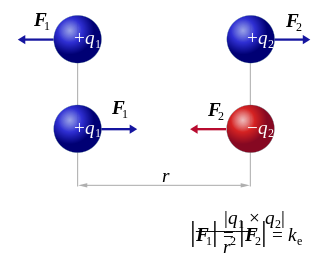

Electrostatic Coulomb force

where the vector,

is the vectorial distance between the charges and,

(a unit vector pointing from q2 to q1).

The vector form of the equation above calculates the force F1 applied on q1 by q2. If r21 is used instead, then the effect on q2 can be found. It can be also calculated using Newton's third law: F2 = -F1.

Electrostatic Coulomb force also known as Coulomb interaction and electrostatic force, named for Charles-Augustin de Coulomb who published the result in 1785, describes the attraction or repulsion of particles due to their electric charge.[19]

Coulomb's law states that:

- The magnitude of the electric force between two point charges is directly proportional to the product of the charges and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them.[20][note 5]

The magnitude of the electrostatic force is proportional to the scalar multiple of the charge magnitudes, and inversely proportional to the square of the distance (i.e. Inverse-square law), and is given by:

or in vector notation:

where q1,q2 are two signed point charges; r-hat being the unit vector direction of the distance r between charges; k is Coulombs constant and ε0 is the permittivity of free space, given in SI units by:[20]

The directions of the forces exerted by the two charges on one another are always along the straight line joining them (the shortest distance), and are vector forces of infinite range; and obey Newtons 3rd law being of equal magnitude and opposite direction. Further, when both charges q1 and q2 have the same sign (either both positive or both negative) the forces between them are repulsive, if they are of opposite sign then the forces are attractive.[20][21] These forces obey an important property called the principle of superposition of forces which states that if a third charge were introduced then the total force acting on that charge is the vector sum of the forces that would be exerted by the other charges individually, this holds for any number of charges.[20] However, Coulomb's Law has been stated for charges in a vacuum, if the space between point charges contains matter then the permittivity of the matter between the charges must be accounted for as follows:

where εr is the relative permittivity or dielectric constant of the space the force acts through, and is dimensionless.[20]

Collisions

If two particles interact with one another in a collision process there are four results possible after the interaction:[22]

Elastic

Elastic scattering is when the collisions between target and incident particles have total conservation of kinetic energy.[23] This implies that there is no breaking up of the particles or energy loss through vibrations,[23][24] that is to say that the internal states of each of the particles remains unchanged.[22] Due to the fact that there is no breaking present, elastic collisions can be modeled as occurring between point-like particles,[24] a principle that is very useful for an elementary particle such as the electron.[22]

Inelastic

Inelastic scattering is when the collisions do not conserve kinetic energy,[23][24] and as such the internal states of one or both of the particles has changed.[22] This is due to energy being converted into vibrations which can be interpreted as heat, waves (sound), or vibrations between constituent particles of either collision party.[23] Particles may also split apart, further energy can be converted into breaking the chemical bonds between components.[23]

Furthermore, momentum is conserved in both elastic and inelastic scattering.[23] The other two results are reactions (when the structure of the interacting particles is changed producing two or more (generally complex particles)), and that new particles that are not constituent elementary particles of the interacting particles are created.[22][23]

Types of scattering

Electron-molecule scattering

Electron scattering by isolated atoms and molecules occurs in the gas phase. It plays a key role in plasma physics and chemistry and it's important for such applications as semiconductor physics. Electron-molecule/atom scattering is normally treated by means of quantum mechanics. The leading approach to compute the cross sections is using R-matrix method.

Compton scattering

Compton scattering, so named for Arthur Compton who first observed the effect in 1922 and which earned him the 1927 Nobel Prize in Physics;[25] is the inelastic scattering of a high-energy photon by a free charged particle.[26][note 6]

This was demonstrated in 1923 by firing radiation of a given wavelength (X-rays in the given case) through a foil (carbon target), which was scattered in a manner inconsistent with classical radiation theory.[26][note 7] Compton published a paper in the Physical Review explaining the phenomenon: A quantum theory of the scattering of X-rays by light elements.[27] The Compton effect can be understood as high-energy photons scattering in-elastically off individual electrons,[26] when the incoming photon gives part of its energy to the electron, then the scattered photon has lower energy and lower frequency and longer wavelength according to the Planck relation:[28]

which gives the energy E of the photon in terms of frequency f or ν, and Planck's constant h (6.626×10−34 J⋅s = 4.136×10−15 eV.s).[29] The wavelength change in such scattering depends only upon the angle of scattering for a given target particle.[28][30]

This was an important discovery during the 1920s when the particle (photon) nature of light suggested by the Photoelectric effect was still being debated, the Compton experiment gave clear and independent evidence of particle-like behavior.[25][30]

The formula describing the Compton shift in the wavelength due to scattering is given by:

where λf is the final wavelength of the photon after scattering, λi is the initial wavelength of the photon before scattering, h is Planck's constant, me is the rest mass of the electron, c is the speed of light and θ is the scattering angle of the photon.[25][30]

The coefficient of (1 - cosθ) is known as the Compton wavelength, but is in fact a proportionality constant for the wavelength shift.[31] The collision causes the photon wavelength to increase by somewhere between 0 (for a scattering angle of 0°) and twice the Compton wavelength (for a scattering angle of 180°).[32]

Thomson scattering is the classical elastic quantitative interpretation of the scattering process,[26] and this can be seen to happen with lower, mid-energy, photons. The classical theory of an electromagnetic wave scattered by charged particles, cannot explain low intensity shifts in wavelength.

Inverse Compton scattering takes place when the electron is moving, and has sufficient kinetic energy compared to the photon. In this case net energy may be transferred from the electron to the photon. The inverse Compton effect is seen in astrophysics when a low energy photon (e.g. of the cosmic microwave background) bounces off a high energy (relativistic) electron. Such electrons are produced in supernovae and active galactic nuclei.[26]

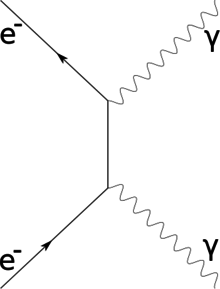

Møller scattering

Mott scattering

Bhabha scattering

Bremsstrahlung scattering

Deep inelastic scattering

Synchrotron emission

If a charged particle such as an electron is accelerated – this can be acceleration in a straight line or motion in a curved path – electromagnetic radiation is emitted by the particle. Within electron storage rings and circular particle accelerators known as synchrotrons, electrons are bent in a circular path and emit X-rays typically. This radially emitted () electromagnetic radiation when charged particles are accelerated is called synchrotron radiation.[33] It is produced in synchrotrons using bending magnets, undulators and/or wigglers.[citation needed]

The first observation came at the General Electric Research Laboratory in Schenectady, New York, on April 24, 1947, in the synchrotron built by a team of Herb Pollack to test the idea of phase-stability principle for RF accelerators.[note 8] When the technician was asked to look around the shielding with a large mirror to check for sparking in the tube, he saw a bright arc of light coming from the electron beam. Robert Langmuir is credited as recognizing it as synchrotron radiation or, as he called it, "Schwinger radiation" after Julian Schwinger.[34]

Classically, the radiated power P from an accelerated electron is:

this comes from the Larmor formula; where K is an electric permittivity constant,[note 9] e is electron charge, c is the speed of light, and a is the acceleration. Within a circular orbit such as a storage ring, the non-relativistic case is simply the centripetal acceleration. However within a storage ring the acceleration is highly relitivistic, and can be obtained as follows:

- ,

where v is the circular velocity, r is the radius of the circular accelerator, m is the rest mass of the charged particle, p is the momentum, τ is the Proper time (t/γ), and γ is the Lorentz factor. Radiated power then becomes:

For highly relativistic particles, such that velocity becomes nearly constant, the γ4 term becomes the dominant variable in determining loss rate, which means that the loss scales as the fourth power of the particle energy γmc2; and the inverse dependence of synchrotron radiation loss on radius argues for building the accelerator as large as possible.[33]

Facilities

SLAC

Stanford Linear Accelerator Center is located near Stanford University, California.[35] Construction began on the 2 mile long linear accelerator in 1962 and was completed in 1967, and in 1968 the first experimental evidence of quarks was discovered resulting in the 1990 Nobel Prize in Physics, shared by SLAC's Richard Taylor and Jerome I. Friedman and Henry Kendall of MIT.[36] The accelerator came with a 20GeV capacity for the electron acceleration, and while similar to Rutherford's scattering experiment, that experiment operated with alpha particles at only 7MeV. In the SLAC case the incident particle was an electron and the target a proton, and due to the short wavelength of the electron (due to its high energy and momentum) it was able to probe into the proton.[35] The Stanford Positron Electron Asymmetric Ring (SPEAR) addition to the SLAC made further such discoveries possible, leading to the discovery in 1974 of the J/psi particle, which consists of a paired charm quark and anti-charm quark, and another Nobel Prize in Physics in 1976. This was followed up with Martin Perl's announcement of the discovery of the tau lepton, for which he shared the 1995 Nobel Prize in Physics.[36]

The SLAC aims to be a premier accelerator laboratory,[37] to pursue strategic programs in particle physics, particle astrophysics and cosmology, as well as the applications in discovering new drugs for healing, new materials for electronics and new ways to produce clean energy and clean up the environment.[38] Under the directorship of Chi-Chang Kao the SLAC's fifth director (as of November 2012), a noted X-ray scientist who came to SLAC in 2010 to serve as associate laboratory director for the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource.[39]

BaBar

SSRL - Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource

Other scientific programs run at SLAC include:[40]

- Advanced Accelerator Research

- ATLAS/Large Hadron Collider

- Elementary Particle Theory

- EXO - Enriched Xenon Observatory

- FACET - Facility for Advanced Accelerator Experimental Tests

- Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope

- Geant4

- KIPAC - Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology

- LCLS - Linac Coherent Light Source

- LSST - Large Synoptic Survey Telescope

- NLCTA - Next Linear Collider Test Accelerator

- Stanford PULSE Institute

- SIMES - Stanford Institute for Materials and Energy Sciences

- SUNCAT Center for Interface Science and Catalysis

- Super CDMS - Super Cryogenic Dark Matter Search

RIKEN RI Beam Factory

RIKEN was founded in 1917 as a private research foundation in Tokyo, and is Japan's largest comprehensive research institution. Having grown rapidly in size and scope, it is today renowned for high-quality research in a diverse range of scientific disciplines, and encompasses a network of world-class research centers and institutes across Japan.[41]

The RIKEN RI Beam Factory, otherwise known as the RIKEN Nishina Centre (for Accelerator-Based Science), is a cyclotron-based research facility which began operating in 2007; 70 years after the first in Japanese cyclotron, from Dr. Yoshio Nishina whose name is given to the facility.[42]

As of 2006, the facility has a world-class heavy-ion accelerator complex. This consists of a K540-MeV ring cyclotron (RRC) and two different injectors: a variable-frequency heavy-ion linac (RILAC) and a K70-MeV AVF cyclotron (AVF). It has a projectile-fragment separator (RIPS) which provides RI (Radioactive Isotope) beams of less than 60 amu, the world's most intense light-atomic-mass RI beams.[43]

Overseen by the Nishina Centre, the RI Beam Factory is utilized by users worldwide promoting research in nuclear, particle and hadron physics. This promotion of accelerator applications research is an important mission of the Nishina Centre, and implements the use of both domestic and oversea accelerator facilities.[44]

SCRIT

The SCRIT (Self-Confining Radioactive isotope Ion Target) facility, is currently under construction at the RIKEN RI beam factory (RIBF) in Japan. The project aims to investigate short-lived nuclei through the use of an elastic electron scattering test of charge density distribution, with initial testing done with stable nuclei. With the first electron scattering off unstable Sn isotopes to take place in 2014.[45]

The investigation of short-lived radioactive nuclei (RI) by means of electron scattering has never been performed because of an inability to make these nuclei a target,[46] now with the advent of a novel self-confining RI technique at the world's first facility dedicated to the study of the structure of short-lived nuclei by electron scattering this research becomes possible. The principle of the technique is based around the ion trapping phenomenon which is observed at electron storage ring facilities,[note 10] which has an adverse effect on the performance of electron storage rings.[45]

The novel idea to be employed at SCRIT is to use the ion trapping to allow short-lived RI's to be made a target, as trapped ions on the electron beam, for the scattering experiments. This idea was first given a proof-of-principle study using the electron storage ring of Kyoto University, KSR; this was done using a stable nucleus of 133Cs as a target in an experiment of 120MeV electron beam energy, 75mA typical stored beam current and a 100 seconds beam lifetime. The results of this study were favorable with elastically scattered electrons from the trapped Cs being clearly visible.[45]

See also

Notes

- ^ The fractional version's denominator is the inverse of the decimal value (along with its relative standard uncertainty of 4.2×10−13 u).

- ^ The electron's charge is the negative of elementary charge, which has a positive value for the proton.

- ^ Further notes can be found in Laming, R. (1845): "Observations on a paper by Prof. Faraday concerning electric conduction and the nature of matter", Phil. Mag. 27, 420-3 and in Farrar, W. F. (1969). "Richard Laming and the coal-gas industry, with his views on the structure of matter". Annals of Science. 25 (3): 243–53. doi:10.1080/00033796900200141.

- ^ Details can be found in Ritchmeyer, Kennard and Lauritsen's (1955) book on atomic physics

- ^ In -- Coulomb (1785a) "Premier mémoire sur l'électricité et le magnétisme," Histoire de l’Académie Royale des Sciences, pages 569-577 -- Coulomb studied the repulsive force between bodies having electrical charges of the same sign:

Page 574 : Il résulte donc de ces trois essais, que l'action répulsive que les deux balles électrifées de la même nature d'électricité exercent l'une sur l'autre, suit la raison inverse du carré des distances.

In -- Coulomb (1785b) "Second mémoire sur l’électricité et le magnétisme," Histoire de l’Académie Royale des Sciences, pages 578-611. -- Coulomb showed that oppositely charged bodies obey an inverse-square law of attraction.Translation : It follows therefore from these three tests, that the repulsive force that the two balls --[that were] electrified with the same kind of electricity -- exert on each other, follows the inverse proportion of the square of the distance.

- ^ An electron in this case. Where the notion of "free" results from considering if the energy of the photon is large compared to the binding energy of the electron; then one could make the approximation that the electron as free.

- ^ For example, x-ray photons have an energy value of several keV. So, both conservation of momentum and energy could be observed. To show this, Compton scattered x-ray radiation off a graphite block and measured the wavelength of the x-rays before and after they were scattered as a function of the scattering angle. He discovered that the scattered x-rays had a longer wavelength than that of the incident radiation.

- ^ The mass of particles in a cyclotron grows as the energy increases into the relativistic range. The heavier particles then arrive too late at the electrodes for a radio-frequency (RF) voltage of fixed frequency to accelerate them, thereby limiting the maximum particle energy. To deal with this problem, in 1945 McMillan in the U. S. and Veksler in the Soviet Union independently proposed decreasing the frequency of the RF voltage as the energy increases to keep the voltage and the particle synchronized. This was a specific application of their phase-stability principle for RF accelerators, which explains how particles that are too fast get less acceleration and slow down relative to their companions while particles that are too slow get more and speed up, thereby resulting in a stable bunch of particles that are accelerated together.

- ^ For SI units it can be calculated as 1/4πε0

- ^ The residual gases in a storage ring are ionized by the circulating electron beam. Once they are ionized, they are trapped transversely by the electron beam. Since the trapped ions stay on the electron beam and kick electrons out of orbit, the results of this ion trapping are harmful for the performance of electron storage rings. This leads to shorter beam lifetime, and even beam instability when the trapping becomes severe. Thus, much effort has been paid so far to reducing the negative effects of ion trapping

References

- ^ a b c d e "CODATA Internationally recommended values of the Fundamental Physical Constants". NIST Standard Reference Database 121. National Institute of Standards and Technology. Retrieved 23 November 2013.

- ^ a b c "electron scattering". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 13 October 2013.

- ^ "Electron scattering in solids". Ioffe Institute. Department of Applied Mathematics and Mathematical Physics. Retrieved 13 October 2013.

- ^ Howe, James; Fultz, Brent (2008). Transmission electron microscopy and diffractometry of materials (3rd ed.). Berlin: Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-73885-5.

- ^ Kohl, L. Reimer, H. (2008). Transmission electron microscopy physics of image formation (5th ed.). New York: Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-34758-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Electron scattering". MATTER. The University of Liverpool. Archived from the original on 15 October 2013. Retrieved 13 October 2013.

- ^ B. Frois; I. Sick, eds. (1991). Modern topics in electron scattering. Singapore: World Scientific. Bibcode:1991mtes.book.....F. ISBN 978-9971509750.

- ^ Drechsel, D.; Giannini, M. M. (1989). "Electron scattering off nuclei". Reports on Progress in Physics. 52 (9): 1083. Bibcode:1989RPPh...52.1083D. doi:10.1088/0034-4885/52/9/002.

- ^ Arabatzis, Theodore (2005). Representing Electrons A Biographical Approach to Theoretical Entities. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226024219.

- ^ a b Springford, ed. by Michael (1997). Electron : a centenary volume (1st ed.). Cambridge [u.a.]: Cambridge Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0521561303.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ^ a b Pendry, J. B. (1974). Low energy electron diffraction : the theory and its application to determination of surface structure. London: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0125505505.

- ^ PANOFSKY, W.K.H. (10 June 1998). "SOME REMARKS ON THE EARLY HISTORY OF HIGH ENERGY ELECTRON–ELECTRON SCATTERING". International Journal of Modern Physics A. 13 (14): 2429–2430. Bibcode:1998IJMPA..13.2429P. doi:10.1142/S0217751X98001219.

- ^ a b c d Fitzpatrick, Richard. "The Lorentz force". University of Texas.

- ^ Nave, R. "Lorentz Force Law". hyperphysics. Georgia State University. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. "Lorentz Force". scienceworld. wolfram research. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- ^ Darrigol, Olivier (2000). Electrodynamics from Ampère to Einstein (Repr. ed.). Oxford [u.a.]: Oxford Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0198505945.

- ^ Kurtus, Ron. "Lorentz Force on Electrical Charges in Magnetic Field". Ron Kurtus' School for Champions. School for Champions. Archived from the original on 16 September 2013. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

- ^ Sands, Feynman, Leighton (2010). Mainly electromagnetism and matter (New millennium ed.). New York: Basic Books. ISBN 9780465024162.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Coulomb force. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e Hugh D. Young; Roger A. Freedman; A. Lewis Ford (2007). Sears and Zemansy's university physics : with modern physics (12e ed.). San Francisco: Pearson Addison Wesley. pp. 716–719, 830. ISBN 9780321501301.

- ^ Nave, R. "Coulomb's Law". hyperphysics. Georgia State University. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Kopaleishvili, Teimuraz (1995). Collision theory : (a short course). Singapore [u.a.]: World Scientific. Bibcode:1995ctsc.book.....K. ISBN 978-9810220983.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Elastic and Inelastic Collisions in Particle Physics". SLAC. Stanford University. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- ^ a b c "Scattering". physics.ox. Oxford University. Archived from the original on 23 October 2013. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- ^ a b c Nave, R. "Compton Scattering". hyperphysics. Georgia State University. Retrieved 28 November 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Neakrase, Jennifer; Neal, Jennifer; Venables, John. "Photoelectrons, Compton and Inverse Compton Scattering". Dept of Physics and Astronomy. Arizona State University. Retrieved 28 November 2013.

- ^ Compton, Arthur (May 1923). "A Quantum Theory of the Scattering of X-rays by Light Elements". Physical Review. 21 (5): 483–502. Bibcode:1923PhRv...21..483C. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.21.483.

- ^ a b Nave, R. "Compton Scattering". hyperphysics. Georgia State University. Retrieved 28 November 2013.

- ^ Nave, R. "The Planck Hypothesis". hyperphysics. Georgia State University. Retrieved 28 November 2013.

- ^ a b c "Compton Scattering". NDT Education Resource Center. Iowa State University. Retrieved 28 November 2013.

- ^ Jones, Andrew Zimmerman. "The Compton Effect". About.com Physics. About.com. Retrieved 28 November 2013.

- ^ Duffy, Andrew; Loewy, Ali. "The Compton Effect". Boston University's Physics department. Boston University. Retrieved 28 November 2013.

- ^ a b Nave, R. "Synchrotron Radiation". hyperphysics. Georgia State University. Retrieved 5 December 2013.

- ^ Robinson, Arthur L. "HISTORY of SYNCHROTRON RADIATION". Center for X-ray Optics and Advanced Light Source. Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. Retrieved 5 December 2013.

- ^ a b Walder, James; O'Sullivan, Jack. "The Stanford Linear Accelerator Center (SLAC)". Physics Department. University Of Oxford. Archived from the original on 23 August 2013. Retrieved 16 November 2013.

- ^ a b "SLAC History". SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory. Stanford University. Retrieved 16 November 2013.

- ^ "Our Vision and Mission". SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory. Stanford University. Archived from the original on 28 November 2013. Retrieved 16 November 2013.

- ^ "SLAC Overview". SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory. Stanford University. Retrieved 16 November 2013.

- ^ "Director's Office". SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory. Stanford University. Retrieved 16 November 2013.

- ^ "Scientific Programs". SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory. Stanford University. Archived from the original on 15 September 2015. Retrieved 16 November 2013.

- ^ "About RIKEN". RIKEN. RIKEN, Japan. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ^ "About Nishina Center - Greeting". Nishina Center. RIKEN Nishina Center for Accelerator-Based Science. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ^ "Facilities - RI Beam Factory (RIBF)". Nishina Center. RIKEN Nishina Center for Accelerator-Based Science. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ^ "About Nishina Center - Research Groups". Nishina Center. RIKEN Nishina Center for Accelerator-Based Science. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ^ a b c Suda, T.; Adachi, T.; Amagai, T.; Enokizono, A.; Hara, M.; Hori, T.; Ichikawa, S.; Kurita, K.; Miyamoto, T.; Ogawara, R.; Ohnishi, T.; Shimakura, Y.; Tamae, T.; Togasaki, M.; Wakasugi, M.; Wang, S.; Yanagi, K. (17 December 2012). "Nuclear physics at the SCRIT electron scattering facility". Progress of Theoretical and Experimental Physics. 2012 (1): 3C008–0. Bibcode:2012PTEP.2012cC008S. doi:10.1093/ptep/pts043.

- ^ Wakasugi, Masanori. "SCRIT Team". RIKEN Research. RIKEN Nishina Center for Accelerator-Based Science. Retrieved 19 November 2013.

External links

- Physics Out Loud: Electron Scattering (video)

- Brightstorm: Compton Scattering (video)

![{\displaystyle \mathbf {F} =q[-\nabla \phi -{\frac {d\mathbf {A} }{dt}}+\nabla (\mathbf {A} \cdot \mathbf {v} )]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e7a85073a0f8338eb41180c17d00046603f4d7b3)