The derivatives of scalars , vectors , and second-order tensors with respect to second-order tensors are of considerable use in continuum mechanics . These derivatives are used in the theories of nonlinear elasticity and plasticity , particularly in the design of algorithms for numerical simulations .[ 1]

The directional derivative provides a systematic way of finding these derivatives.[ 2]

Derivatives with respect to vectors and second-order tensors

The definitions of directional derivatives for various situations are given below. It is assumed that the functions are sufficiently smooth that derivatives can be taken.

Derivatives of scalar valued functions of vectors

Let f (v ) be a real valued function of the vector v . Then the derivative of f (v ) with respect to v (or at v ) is the vector defined through its dot product with any vector u being

∂

f

∂

v

⋅

u

=

D

f

(

v

)

[

u

]

=

[

d

d

α

f

(

v

+

α

u

)

]

α

=

0

{\displaystyle {\frac {\partial f}{\partial \mathbf {v} }}\cdot \mathbf {u} =Df(\mathbf {v} )[\mathbf {u} ]=\left[{\frac {\rm {d}}{{\rm {d}}\alpha }}~f(\mathbf {v} +\alpha ~\mathbf {u} )\right]_{\alpha =0}}

for all vectors u . The above dot product yields a scalar, and if u is a unit vector gives the directional derivative of f at v , in the u direction.

Properties:

If

f

(

v

)

=

f

1

(

v

)

+

f

2

(

v

)

{\displaystyle f(\mathbf {v} )=f_{1}(\mathbf {v} )+f_{2}(\mathbf {v} )}

∂

f

∂

v

⋅

u

=

(

∂

f

1

∂

v

+

∂

f

2

∂

v

)

⋅

u

{\displaystyle {\frac {\partial f}{\partial \mathbf {v} }}\cdot \mathbf {u} =\left({\frac {\partial f_{1}}{\partial \mathbf {v} }}+{\frac {\partial f_{2}}{\partial \mathbf {v} }}\right)\cdot \mathbf {u} }

If

f

(

v

)

=

f

1

(

v

)

f

2

(

v

)

{\displaystyle f(\mathbf {v} )=f_{1}(\mathbf {v} )~f_{2}(\mathbf {v} )}

∂

f

∂

v

⋅

u

=

(

∂

f

1

∂

v

⋅

u

)

f

2

(

v

)

+

f

1

(

v

)

(

∂

f

2

∂

v

⋅

u

)

{\displaystyle {\frac {\partial f}{\partial \mathbf {v} }}\cdot \mathbf {u} =\left({\frac {\partial f_{1}}{\partial \mathbf {v} }}\cdot \mathbf {u} \right)~f_{2}(\mathbf {v} )+f_{1}(\mathbf {v} )~\left({\frac {\partial f_{2}}{\partial \mathbf {v} }}\cdot \mathbf {u} \right)}

If

f

(

v

)

=

f

1

(

f

2

(

v

)

)

{\displaystyle f(\mathbf {v} )=f_{1}(f_{2}(\mathbf {v} ))}

∂

f

∂

v

⋅

u

=

∂

f

1

∂

f

2

∂

f

2

∂

v

⋅

u

{\displaystyle {\frac {\partial f}{\partial \mathbf {v} }}\cdot \mathbf {u} ={\frac {\partial f_{1}}{\partial f_{2}}}~{\frac {\partial f_{2}}{\partial \mathbf {v} }}\cdot \mathbf {u} }

Derivatives of vector valued functions of vectors

Let f (v ) be a vector valued function of the vector v . Then the derivative of f (v ) with respect to v (or at v ) is the second order tensor defined through its dot product with any vector u being

∂

f

∂

v

⋅

u

=

D

f

(

v

)

[

u

]

=

[

d

d

α

f

(

v

+

α

u

)

]

α

=

0

{\displaystyle {\frac {\partial \mathbf {f} }{\partial \mathbf {v} }}\cdot \mathbf {u} =D\mathbf {f} (\mathbf {v} )[\mathbf {u} ]=\left[{\frac {\rm {d}}{{\rm {d}}\alpha }}~\mathbf {f} (\mathbf {v} +\alpha ~\mathbf {u} )\right]_{\alpha =0}}

for all vectors u . The above dot product yields a vector, and if u is a unit vector gives the direction derivative of f at v , in the directional u .

Properties:

If

f

(

v

)

=

f

1

(

v

)

+

f

2

(

v

)

{\displaystyle \mathbf {f} (\mathbf {v} )=\mathbf {f} _{1}(\mathbf {v} )+\mathbf {f} _{2}(\mathbf {v} )}

∂

f

∂

v

⋅

u

=

(

∂

f

1

∂

v

+

∂

f

2

∂

v

)

⋅

u

{\displaystyle {\frac {\partial \mathbf {f} }{\partial \mathbf {v} }}\cdot \mathbf {u} =\left({\frac {\partial \mathbf {f} _{1}}{\partial \mathbf {v} }}+{\frac {\partial \mathbf {f} _{2}}{\partial \mathbf {v} }}\right)\cdot \mathbf {u} }

If

f

(

v

)

=

f

1

(

v

)

×

f

2

(

v

)

{\displaystyle \mathbf {f} (\mathbf {v} )=\mathbf {f} _{1}(\mathbf {v} )\times \mathbf {f} _{2}(\mathbf {v} )}

∂

f

∂

v

⋅

u

=

(

∂

f

1

∂

v

⋅

u

)

×

f

2

(

v

)

+

f

1

(

v

)

×

(

∂

f

2

∂

v

⋅

u

)

{\displaystyle {\frac {\partial \mathbf {f} }{\partial \mathbf {v} }}\cdot \mathbf {u} =\left({\frac {\partial \mathbf {f} _{1}}{\partial \mathbf {v} }}\cdot \mathbf {u} \right)\times \mathbf {f} _{2}(\mathbf {v} )+\mathbf {f} _{1}(\mathbf {v} )\times \left({\frac {\partial \mathbf {f} _{2}}{\partial \mathbf {v} }}\cdot \mathbf {u} \right)}

If

f

(

v

)

=

f

1

(

f

2

(

v

)

)

{\displaystyle \mathbf {f} (\mathbf {v} )=\mathbf {f} _{1}(\mathbf {f} _{2}(\mathbf {v} ))}

∂

f

∂

v

⋅

u

=

∂

f

1

∂

f

2

⋅

(

∂

f

2

∂

v

⋅

u

)

{\displaystyle {\frac {\partial \mathbf {f} }{\partial \mathbf {v} }}\cdot \mathbf {u} ={\frac {\partial \mathbf {f} _{1}}{\partial \mathbf {f} _{2}}}\cdot \left({\frac {\partial \mathbf {f} _{2}}{\partial \mathbf {v} }}\cdot \mathbf {u} \right)}

Derivatives of scalar valued functions of second-order tensors

Let

f

(

S

)

{\displaystyle f({\boldsymbol {S}})}

S

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {S}}}

f

(

S

)

{\displaystyle f({\boldsymbol {S}})}

S

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {S}}}

S

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {S}}}

T

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {T}}}

second order tensor defined as

∂

f

∂

S

:

T

=

D

f

(

S

)

[

T

]

=

[

d

d

α

f

(

S

+

α

T

)

]

α

=

0

{\displaystyle {\frac {\partial f}{\partial {\boldsymbol {S}}}}:{\boldsymbol {T}}=Df({\boldsymbol {S}})[{\boldsymbol {T}}]=\left[{\frac {\rm {d}}{{\rm {d}}\alpha }}~f({\boldsymbol {S}}+\alpha ~{\boldsymbol {T}})\right]_{\alpha =0}}

for all second order tensors

T

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {T}}}

Properties:

If

f

(

S

)

=

f

1

(

S

)

+

f

2

(

S

)

{\displaystyle f({\boldsymbol {S}})=f_{1}({\boldsymbol {S}})+f_{2}({\boldsymbol {S}})}

∂

f

∂

S

:

T

=

(

∂

f

1

∂

S

+

∂

f

2

∂

S

)

:

T

{\displaystyle {\frac {\partial f}{\partial {\boldsymbol {S}}}}:{\boldsymbol {T}}=\left({\frac {\partial f_{1}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {S}}}}+{\frac {\partial f_{2}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {S}}}}\right):{\boldsymbol {T}}}

If

f

(

S

)

=

f

1

(

S

)

f

2

(

S

)

{\displaystyle f({\boldsymbol {S}})=f_{1}({\boldsymbol {S}})~f_{2}({\boldsymbol {S}})}

∂

f

∂

S

:

T

=

(

∂

f

1

∂

S

:

T

)

f

2

(

S

)

+

f

1

(

S

)

(

∂

f

2

∂

S

:

T

)

{\displaystyle {\frac {\partial f}{\partial {\boldsymbol {S}}}}:{\boldsymbol {T}}=\left({\frac {\partial f_{1}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {S}}}}:{\boldsymbol {T}}\right)~f_{2}({\boldsymbol {S}})+f_{1}({\boldsymbol {S}})~\left({\frac {\partial f_{2}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {S}}}}:{\boldsymbol {T}}\right)}

If

f

(

S

)

=

f

1

(

f

2

(

S

)

)

{\displaystyle f({\boldsymbol {S}})=f_{1}(f_{2}({\boldsymbol {S}}))}

∂

f

∂

S

:

T

=

∂

f

1

∂

f

2

(

∂

f

2

∂

S

:

T

)

{\displaystyle {\frac {\partial f}{\partial {\boldsymbol {S}}}}:{\boldsymbol {T}}={\frac {\partial f_{1}}{\partial f_{2}}}~\left({\frac {\partial f_{2}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {S}}}}:{\boldsymbol {T}}\right)}

Derivatives of tensor valued functions of second-order tensors

Let

F

(

S

)

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {F}}({\boldsymbol {S}})}

S

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {S}}}

F

(

S

)

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {F}}({\boldsymbol {S}})}

S

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {S}}}

S

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {S}}}

T

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {T}}}

fourth order tensor defined as

∂

F

∂

S

:

T

=

D

F

(

S

)

[

T

]

=

[

d

d

α

F

(

S

+

α

T

)

]

α

=

0

{\displaystyle {\frac {\partial {\boldsymbol {F}}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {S}}}}:{\boldsymbol {T}}=D{\boldsymbol {F}}({\boldsymbol {S}})[{\boldsymbol {T}}]=\left[{\frac {\rm {d}}{{\rm {d}}\alpha }}~{\boldsymbol {F}}({\boldsymbol {S}}+\alpha ~{\boldsymbol {T}})\right]_{\alpha =0}}

for all second order tensors

T

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {T}}}

Properties:

If

F

(

S

)

=

F

1

(

S

)

+

F

2

(

S

)

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {F}}({\boldsymbol {S}})={\boldsymbol {F}}_{1}({\boldsymbol {S}})+{\boldsymbol {F}}_{2}({\boldsymbol {S}})}

∂

F

∂

S

:

T

=

(

∂

F

1

∂

S

+

∂

F

2

∂

S

)

:

T

{\displaystyle {\frac {\partial {\boldsymbol {F}}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {S}}}}:{\boldsymbol {T}}=\left({\frac {\partial {\boldsymbol {F}}_{1}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {S}}}}+{\frac {\partial {\boldsymbol {F}}_{2}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {S}}}}\right):{\boldsymbol {T}}}

If

F

(

S

)

=

F

1

(

S

)

⋅

F

2

(

S

)

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {F}}({\boldsymbol {S}})={\boldsymbol {F}}_{1}({\boldsymbol {S}})\cdot {\boldsymbol {F}}_{2}({\boldsymbol {S}})}

∂

F

∂

S

:

T

=

(

∂

F

1

∂

S

:

T

)

⋅

F

2

(

S

)

+

F

1

(

S

)

⋅

(

∂

F

2

∂

S

:

T

)

{\displaystyle {\frac {\partial {\boldsymbol {F}}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {S}}}}:{\boldsymbol {T}}=\left({\frac {\partial {\boldsymbol {F}}_{1}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {S}}}}:{\boldsymbol {T}}\right)\cdot {\boldsymbol {F}}_{2}({\boldsymbol {S}})+{\boldsymbol {F}}_{1}({\boldsymbol {S}})\cdot \left({\frac {\partial {\boldsymbol {F}}_{2}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {S}}}}:{\boldsymbol {T}}\right)}

If

F

(

S

)

=

F

1

(

F

2

(

S

)

)

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {F}}({\boldsymbol {S}})={\boldsymbol {F}}_{1}({\boldsymbol {F}}_{2}({\boldsymbol {S}}))}

∂

F

∂

S

:

T

=

∂

F

1

∂

F

2

:

(

∂

F

2

∂

S

:

T

)

{\displaystyle {\frac {\partial {\boldsymbol {F}}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {S}}}}:{\boldsymbol {T}}={\frac {\partial {\boldsymbol {F}}_{1}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {F}}_{2}}}:\left({\frac {\partial {\boldsymbol {F}}_{2}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {S}}}}:{\boldsymbol {T}}\right)}

If

f

(

S

)

=

f

1

(

F

2

(

S

)

)

{\displaystyle f({\boldsymbol {S}})=f_{1}({\boldsymbol {F}}_{2}({\boldsymbol {S}}))}

∂

f

∂

S

:

T

=

∂

f

1

∂

F

2

:

(

∂

F

2

∂

S

:

T

)

{\displaystyle {\frac {\partial f}{\partial {\boldsymbol {S}}}}:{\boldsymbol {T}}={\frac {\partial f_{1}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {F}}_{2}}}:\left({\frac {\partial {\boldsymbol {F}}_{2}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {S}}}}:{\boldsymbol {T}}\right)}

Gradient of a tensor field

The gradient ,

∇

T

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {\nabla }}{\boldsymbol {T}}}

T

(

x

)

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {T}}(\mathbf {x} )}

c is defined as:

∇

T

⋅

c

=

lim

α

→

0

d

d

α

T

(

x

+

α

c

)

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {\nabla }}{\boldsymbol {T}}\cdot \mathbf {c} =\lim _{\alpha \rightarrow 0}\quad {\cfrac {d}{d\alpha }}~{\boldsymbol {T}}(\mathbf {x} +\alpha \mathbf {c} )}

The gradient of a tensor field of order n is a tensor field of order n +1.

Cartesian coordinates

If

e

1

,

e

2

,

e

3

{\displaystyle \mathbf {e} _{1},\mathbf {e} _{2},\mathbf {e} _{3}}

Cartesian coordinate system, with coordinates of points denoted by (

x

1

,

x

2

,

x

3

{\displaystyle x_{1},x_{2},x_{3}}

T

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {T}}}

∇

T

=

∂

T

∂

x

i

⊗

e

i

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {\nabla }}{\boldsymbol {T}}={\cfrac {\partial {\boldsymbol {T}}}{\partial x_{i}}}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{i}}

Since the basis vectors do not vary in a Cartesian coordinate system we have the following relations for the gradients of a scalar field

ϕ

{\displaystyle \phi }

v , and a second-order tensor field

S

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {S}}}

∇

ϕ

=

∂

ϕ

∂

x

i

e

i

=

ϕ

,

i

e

i

∇

v

=

∂

(

v

j

e

j

)

∂

x

i

⊗

e

i

=

∂

v

j

∂

x

i

e

j

⊗

e

i

=

v

j

,

i

e

j

⊗

e

i

∇

S

=

∂

(

S

j

k

e

j

⊗

e

k

)

∂

x

i

⊗

e

i

=

∂

S

j

k

∂

x

i

e

j

⊗

e

k

⊗

e

i

=

S

j

k

,

i

e

j

⊗

e

k

⊗

e

i

{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}{\boldsymbol {\nabla }}\phi &={\cfrac {\partial \phi }{\partial x_{i}}}~\mathbf {e} _{i}=\phi _{,i}~\mathbf {e} _{i}\\{\boldsymbol {\nabla }}\mathbf {v} &={\cfrac {\partial (v_{j}\mathbf {e} _{j})}{\partial x_{i}}}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{i}={\cfrac {\partial v_{j}}{\partial x_{i}}}~\mathbf {e} _{j}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{i}=v_{j,i}~\mathbf {e} _{j}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{i}\\{\boldsymbol {\nabla }}{\boldsymbol {S}}&={\cfrac {\partial (S_{jk}\mathbf {e} _{j}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{k})}{\partial x_{i}}}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{i}={\cfrac {\partial S_{jk}}{\partial x_{i}}}~\mathbf {e} _{j}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{k}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{i}=S_{jk,i}~\mathbf {e} _{j}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{k}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{i}\end{aligned}}}

Curvilinear coordinates

If

g

1

,

g

2

,

g

3

{\displaystyle \mathbf {g} ^{1},\mathbf {g} ^{2},\mathbf {g} ^{3}}

contravariant basis vectors in a curvilinear coordinate system, with coordinates of points denoted by (

ξ

1

,

ξ

2

,

ξ

3

{\displaystyle \xi ^{1},\xi ^{2},\xi ^{3}}

T

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {T}}}

[ 3]

∇

T

=

∂

T

∂

ξ

i

⊗

g

i

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {\nabla }}{\boldsymbol {T}}={\frac {\partial {\boldsymbol {T}}}{\partial \xi ^{i}}}\otimes \mathbf {g} ^{i}}

From this definition we have the following relations for the gradients of a scalar field

ϕ

{\displaystyle \phi }

v , and a second-order tensor field

S

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {S}}}

∇

ϕ

=

∂

ϕ

∂

ξ

i

g

i

∇

v

=

∂

(

v

j

g

j

)

∂

ξ

i

⊗

g

i

=

(

∂

v

j

∂

ξ

i

+

v

k

Γ

i

k

j

)

g

j

⊗

g

i

=

(

∂

v

j

∂

ξ

i

−

v

k

Γ

i

j

k

)

g

j

⊗

g

i

∇

S

=

∂

(

S

j

k

g

j

⊗

g

k

)

∂

ξ

i

⊗

g

i

=

(

∂

S

j

k

∂

ξ

i

−

S

l

k

Γ

i

j

l

−

S

j

l

Γ

i

k

l

)

g

j

⊗

g

k

⊗

g

i

{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}{\boldsymbol {\nabla }}\phi &={\frac {\partial \phi }{\partial \xi ^{i}}}~\mathbf {g} ^{i}\\{\boldsymbol {\nabla }}\mathbf {v} &={\frac {\partial \left(v^{j}\mathbf {g} _{j}\right)}{\partial \xi ^{i}}}\otimes \mathbf {g} ^{i}=\left({\frac {\partial v^{j}}{\partial \xi ^{i}}}+v^{k}~\Gamma _{ik}^{j}\right)~\mathbf {g} _{j}\otimes \mathbf {g} ^{i}=\left({\frac {\partial v_{j}}{\partial \xi ^{i}}}-v_{k}~\Gamma _{ij}^{k}\right)~\mathbf {g} ^{j}\otimes \mathbf {g} ^{i}\\{\boldsymbol {\nabla }}{\boldsymbol {S}}&={\frac {\partial \left(S_{jk}~\mathbf {g} ^{j}\otimes \mathbf {g} ^{k}\right)}{\partial \xi ^{i}}}\otimes \mathbf {g} ^{i}=\left({\frac {\partial S_{jk}}{\partial \xi _{i}}}-S_{lk}~\Gamma _{ij}^{l}-S_{jl}~\Gamma _{ik}^{l}\right)~\mathbf {g} ^{j}\otimes \mathbf {g} ^{k}\otimes \mathbf {g} ^{i}\end{aligned}}}

where the Christoffel symbol

Γ

i

j

k

{\displaystyle \Gamma _{ij}^{k}}

Γ

i

j

k

g

k

=

∂

g

i

∂

ξ

j

⟹

Γ

i

j

k

=

∂

g

i

∂

ξ

j

⋅

g

k

=

−

g

i

⋅

∂

g

k

∂

ξ

j

{\displaystyle \Gamma _{ij}^{k}~\mathbf {g} _{k}={\frac {\partial \mathbf {g} _{i}}{\partial \xi ^{j}}}\quad \implies \quad \Gamma _{ij}^{k}={\frac {\partial \mathbf {g} _{i}}{\partial \xi ^{j}}}\cdot \mathbf {g} ^{k}=-\mathbf {g} _{i}\cdot {\frac {\partial \mathbf {g} ^{k}}{\partial \xi ^{j}}}}

Cylindrical polar coordinates

In cylindrical coordinates , the gradient is given by

∇

ϕ

=

∂

ϕ

∂

r

e

r

+

1

r

∂

ϕ

∂

θ

e

θ

+

∂

ϕ

∂

z

e

z

∇

v

=

∂

v

r

∂

r

e

r

⊗

e

r

+

∂

v

θ

∂

r

e

r

⊗

e

θ

+

∂

v

z

∂

r

e

r

⊗

e

z

+

1

r

(

∂

v

r

∂

θ

−

v

θ

)

e

θ

⊗

e

r

+

1

r

(

∂

v

θ

∂

θ

+

v

r

)

e

θ

⊗

e

θ

+

1

r

∂

v

z

∂

θ

e

θ

⊗

e

z

+

∂

v

r

∂

z

e

z

⊗

e

r

+

∂

v

θ

∂

z

e

z

⊗

e

θ

+

∂

v

z

∂

z

e

z

⊗

e

z

∇

S

=

∂

S

r

r

∂

r

e

r

⊗

e

r

⊗

e

r

+

∂

S

r

r

∂

z

e

r

⊗

e

r

⊗

e

z

+

1

r

[

∂

S

r

r

∂

θ

−

(

S

θ

r

+

S

r

θ

)

]

e

r

⊗

e

r

⊗

e

θ

+

∂

S

r

θ

∂

r

e

r

⊗

e

θ

⊗

e

r

+

∂

S

r

θ

∂

z

e

r

⊗

e

θ

⊗

e

z

+

1

r

[

∂

S

r

θ

∂

θ

+

(

S

r

r

−

S

θ

θ

)

]

e

r

⊗

e

θ

⊗

e

θ

+

∂

S

r

z

∂

r

e

r

⊗

e

z

⊗

e

r

+

∂

S

r

z

∂

z

e

r

⊗

e

z

⊗

e

z

+

1

r

[

∂

S

r

z

∂

θ

−

S

θ

z

]

e

r

⊗

e

z

⊗

e

θ

+

∂

S

θ

r

∂

r

e

θ

⊗

e

r

⊗

e

r

+

∂

S

θ

r

∂

z

e

θ

⊗

e

r

⊗

e

z

+

1

r

[

∂

S

θ

r

∂

θ

+

(

S

r

r

−

S

θ

θ

)

]

e

θ

⊗

e

r

⊗

e

θ

+

∂

S

θ

θ

∂

r

e

θ

⊗

e

θ

⊗

e

r

+

∂

S

θ

θ

∂

z

e

θ

⊗

e

θ

⊗

e

z

+

1

r

[

∂

S

θ

θ

∂

θ

+

(

S

r

θ

+

S

θ

r

)

]

e

θ

⊗

e

θ

⊗

e

θ

+

∂

S

θ

z

∂

r

e

θ

⊗

e

z

⊗

e

r

+

∂

S

θ

z

∂

z

e

θ

⊗

e

z

⊗

e

z

+

1

r

[

∂

S

θ

z

∂

θ

+

S

r

z

]

e

θ

⊗

e

z

⊗

e

θ

+

∂

S

z

r

∂

r

e

z

⊗

e

r

⊗

e

r

+

∂

S

z

r

∂

z

e

z

⊗

e

r

⊗

e

z

+

1

r

[

∂

S

z

r

∂

θ

−

S

z

θ

]

e

z

⊗

e

r

⊗

e

θ

+

∂

S

z

θ

∂

r

e

z

⊗

e

θ

⊗

e

r

+

∂

S

z

θ

∂

z

e

z

⊗

e

θ

⊗

e

z

+

1

r

[

∂

S

z

θ

∂

θ

+

S

z

r

]

e

z

⊗

e

θ

⊗

e

θ

+

∂

S

z

z

∂

r

e

z

⊗

e

z

⊗

e

r

+

∂

S

z

z

∂

z

e

z

⊗

e

z

⊗

e

z

+

1

r

∂

S

z

z

∂

θ

e

z

⊗

e

z

⊗

e

θ

{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}{\boldsymbol {\nabla }}\phi ={}\quad &{\frac {\partial \phi }{\partial r}}~\mathbf {e} _{r}+{\frac {1}{r}}~{\frac {\partial \phi }{\partial \theta }}~\mathbf {e} _{\theta }+{\frac {\partial \phi }{\partial z}}~\mathbf {e} _{z}\\{\boldsymbol {\nabla }}\mathbf {v} ={}\quad &{\frac {\partial v_{r}}{\partial r}}~\mathbf {e} _{r}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{r}+{\frac {\partial v_{\theta }}{\partial r}}~\mathbf {e} _{r}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{\theta }+{\frac {\partial v_{z}}{\partial r}}~\mathbf {e} _{r}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{z}\\{}+{}&{\frac {1}{r}}\left({\frac {\partial v_{r}}{\partial \theta }}-v_{\theta }\right)~\mathbf {e} _{\theta }\otimes \mathbf {e} _{r}+{\frac {1}{r}}\left({\frac {\partial v_{\theta }}{\partial \theta }}+v_{r}\right)~\mathbf {e} _{\theta }\otimes \mathbf {e} _{\theta }+{\frac {1}{r}}{\frac {\partial v_{z}}{\partial \theta }}~\mathbf {e} _{\theta }\otimes \mathbf {e} _{z}\\{}+{}&{\frac {\partial v_{r}}{\partial z}}~\mathbf {e} _{z}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{r}+{\frac {\partial v_{\theta }}{\partial z}}~\mathbf {e} _{z}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{\theta }+{\frac {\partial v_{z}}{\partial z}}~\mathbf {e} _{z}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{z}\\{\boldsymbol {\nabla }}{\boldsymbol {S}}={}\quad &{\frac {\partial S_{rr}}{\partial r}}~\mathbf {e} _{r}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{r}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{r}+{\frac {\partial S_{rr}}{\partial z}}~\mathbf {e} _{r}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{r}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{z}+{\frac {1}{r}}\left[{\frac {\partial S_{rr}}{\partial \theta }}-(S_{\theta r}+S_{r\theta })\right]~\mathbf {e} _{r}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{r}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{\theta }\\{}+{}&{\frac {\partial S_{r\theta }}{\partial r}}~\mathbf {e} _{r}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{\theta }\otimes \mathbf {e} _{r}+{\frac {\partial S_{r\theta }}{\partial z}}~\mathbf {e} _{r}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{\theta }\otimes \mathbf {e} _{z}+{\frac {1}{r}}\left[{\frac {\partial S_{r\theta }}{\partial \theta }}+(S_{rr}-S_{\theta \theta })\right]~\mathbf {e} _{r}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{\theta }\otimes \mathbf {e} _{\theta }\\{}+{}&{\frac {\partial S_{rz}}{\partial r}}~\mathbf {e} _{r}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{z}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{r}+{\frac {\partial S_{rz}}{\partial z}}~\mathbf {e} _{r}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{z}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{z}+{\frac {1}{r}}\left[{\frac {\partial S_{rz}}{\partial \theta }}-S_{\theta z}\right]~\mathbf {e} _{r}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{z}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{\theta }\\{}+{}&{\frac {\partial S_{\theta r}}{\partial r}}~\mathbf {e} _{\theta }\otimes \mathbf {e} _{r}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{r}+{\frac {\partial S_{\theta r}}{\partial z}}~\mathbf {e} _{\theta }\otimes \mathbf {e} _{r}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{z}+{\frac {1}{r}}\left[{\frac {\partial S_{\theta r}}{\partial \theta }}+(S_{rr}-S_{\theta \theta })\right]~\mathbf {e} _{\theta }\otimes \mathbf {e} _{r}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{\theta }\\{}+{}&{\frac {\partial S_{\theta \theta }}{\partial r}}~\mathbf {e} _{\theta }\otimes \mathbf {e} _{\theta }\otimes \mathbf {e} _{r}+{\frac {\partial S_{\theta \theta }}{\partial z}}~\mathbf {e} _{\theta }\otimes \mathbf {e} _{\theta }\otimes \mathbf {e} _{z}+{\frac {1}{r}}\left[{\frac {\partial S_{\theta \theta }}{\partial \theta }}+(S_{r\theta }+S_{\theta r})\right]~\mathbf {e} _{\theta }\otimes \mathbf {e} _{\theta }\otimes \mathbf {e} _{\theta }\\{}+{}&{\frac {\partial S_{\theta z}}{\partial r}}~\mathbf {e} _{\theta }\otimes \mathbf {e} _{z}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{r}+{\frac {\partial S_{\theta z}}{\partial z}}~\mathbf {e} _{\theta }\otimes \mathbf {e} _{z}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{z}+{\frac {1}{r}}\left[{\frac {\partial S_{\theta z}}{\partial \theta }}+S_{rz}\right]~\mathbf {e} _{\theta }\otimes \mathbf {e} _{z}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{\theta }\\{}+{}&{\frac {\partial S_{zr}}{\partial r}}~\mathbf {e} _{z}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{r}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{r}+{\frac {\partial S_{zr}}{\partial z}}~\mathbf {e} _{z}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{r}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{z}+{\frac {1}{r}}\left[{\frac {\partial S_{zr}}{\partial \theta }}-S_{z\theta }\right]~\mathbf {e} _{z}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{r}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{\theta }\\{}+{}&{\frac {\partial S_{z\theta }}{\partial r}}~\mathbf {e} _{z}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{\theta }\otimes \mathbf {e} _{r}+{\frac {\partial S_{z\theta }}{\partial z}}~\mathbf {e} _{z}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{\theta }\otimes \mathbf {e} _{z}+{\frac {1}{r}}\left[{\frac {\partial S_{z\theta }}{\partial \theta }}+S_{zr}\right]~\mathbf {e} _{z}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{\theta }\otimes \mathbf {e} _{\theta }\\{}+{}&{\frac {\partial S_{zz}}{\partial r}}~\mathbf {e} _{z}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{z}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{r}+{\frac {\partial S_{zz}}{\partial z}}~\mathbf {e} _{z}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{z}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{z}+{\frac {1}{r}}~{\frac {\partial S_{zz}}{\partial \theta }}~\mathbf {e} _{z}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{z}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{\theta }\end{aligned}}}

Divergence of a tensor field

The divergence of a tensor field

T

(

x

)

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {T}}(\mathbf {x} )}

(

∇

⋅

T

)

⋅

c

=

∇

⋅

(

c

⋅

T

T

)

;

∇

⋅

v

=

tr

(

∇

v

)

{\displaystyle ({\boldsymbol {\nabla }}\cdot {\boldsymbol {T}})\cdot \mathbf {c} ={\boldsymbol {\nabla }}\cdot \left(\mathbf {c} \cdot {\boldsymbol {T}}^{\textsf {T}}\right)~;\qquad {\boldsymbol {\nabla }}\cdot \mathbf {v} ={\text{tr}}({\boldsymbol {\nabla }}\mathbf {v} )}

where c is an arbitrary constant vector and v is a vector field. If

T

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {T}}}

n > 1 then the divergence of the field is a tensor of order n − 1.

Cartesian coordinates

In a Cartesian coordinate system we have the following relations for a vector field v and a second-order tensor field

S

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {S}}}

∇

⋅

v

=

∂

v

i

∂

x

i

=

v

i

,

i

∇

⋅

S

=

∂

S

k

i

∂

x

k

e

i

=

S

k

i

,

k

e

i

{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}{\boldsymbol {\nabla }}\cdot \mathbf {v} &={\frac {\partial v_{i}}{\partial x_{i}}}=v_{i,i}\\{\boldsymbol {\nabla }}\cdot {\boldsymbol {S}}&={\frac {\partial S_{ki}}{\partial x_{k}}}~\mathbf {e} _{i}=S_{ki,k}~\mathbf {e} _{i}\end{aligned}}}

where tensor index notation for partial derivatives is used in the rightmost expressions. The last relation can be found in reference [ 4]

According to the same paper in the case of the second-order tensor field:

∇

⋅

S

≠

div

S

=

∇

⋅

S

T

.

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {\nabla }}\cdot {\boldsymbol {S}}\neq \operatorname {div} {\boldsymbol {S}}={\boldsymbol {\nabla }}\cdot {\boldsymbol {S}}^{\textsf {T}}.}

Importantly, other written conventions for the divergence of a second-order tensor do exist. For example, in a Cartesian coordinate system the divergence of a second rank tensor can also be written as[ 5]

∇

⋅

S

=

∂

S

k

i

∂

x

i

e

k

=

S

k

i

,

i

e

k

{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}{\boldsymbol {\nabla }}\cdot {\boldsymbol {S}}&={\cfrac {\partial S_{ki}}{\partial x_{i}}}~\mathbf {e} _{k}=S_{ki,i}~\mathbf {e} _{k}\end{aligned}}}

The difference stems from whether the differentiation is performed with respect to the rows or columns of

S

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {S}}}

S

{\displaystyle \mathbf {S} }

v

{\displaystyle \mathbf {v} }

∇

⋅

(

∇

v

)

=

∇

⋅

(

v

i

,

j

e

i

⊗

e

j

)

=

v

i

,

j

i

e

i

⋅

e

i

⊗

e

j

=

(

∇

⋅

v

)

,

j

e

j

=

∇

(

∇

⋅

v

)

∇

⋅

[

(

∇

v

)

T

]

=

∇

⋅

(

v

j

,

i

e

i

⊗

e

j

)

=

v

j

,

i

i

e

i

⋅

e

i

⊗

e

j

=

∇

2

v

j

e

j

=

∇

2

v

{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}{\boldsymbol {\nabla }}\cdot \left({\boldsymbol {\nabla }}\mathbf {v} \right)&={\boldsymbol {\nabla }}\cdot \left(v_{i,j}~\mathbf {e} _{i}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{j}\right)=v_{i,ji}~\mathbf {e} _{i}\cdot \mathbf {e} _{i}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{j}=\left({\boldsymbol {\nabla }}\cdot \mathbf {v} \right)_{,j}~\mathbf {e} _{j}={\boldsymbol {\nabla }}\left({\boldsymbol {\nabla }}\cdot \mathbf {v} \right)\\{\boldsymbol {\nabla }}\cdot \left[\left({\boldsymbol {\nabla }}\mathbf {v} \right)^{\textsf {T}}\right]&={\boldsymbol {\nabla }}\cdot \left(v_{j,i}~\mathbf {e} _{i}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{j}\right)=v_{j,ii}~\mathbf {e} _{i}\cdot \mathbf {e} _{i}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{j}={\boldsymbol {\nabla }}^{2}v_{j}~\mathbf {e} _{j}={\boldsymbol {\nabla }}^{2}\mathbf {v} \end{aligned}}}

The last equation is equivalent to the alternative definition / interpretation[ 5]

(

∇

⋅

)

alt

(

∇

v

)

=

(

∇

⋅

)

alt

(

v

i

,

j

e

i

⊗

e

j

)

=

v

i

,

j

j

e

i

⊗

e

j

⋅

e

j

=

∇

2

v

i

e

i

=

∇

2

v

{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\left({\boldsymbol {\nabla }}\cdot \right)_{\text{alt}}\left({\boldsymbol {\nabla }}\mathbf {v} \right)=\left({\boldsymbol {\nabla }}\cdot \right)_{\text{alt}}\left(v_{i,j}~\mathbf {e} _{i}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{j}\right)=v_{i,jj}~\mathbf {e} _{i}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{j}\cdot \mathbf {e} _{j}={\boldsymbol {\nabla }}^{2}v_{i}~\mathbf {e} _{i}={\boldsymbol {\nabla }}^{2}\mathbf {v} \end{aligned}}}

Curvilinear coordinates

In curvilinear coordinates, the divergences of a vector field v and a second-order tensor field

S

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {S}}}

∇

⋅

v

=

(

∂

v

i

∂

ξ

i

+

v

k

Γ

i

k

i

)

∇

⋅

S

=

(

∂

S

i

k

∂

ξ

i

−

S

l

k

Γ

i

i

l

−

S

i

l

Γ

i

k

l

)

g

k

{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}{\boldsymbol {\nabla }}\cdot \mathbf {v} &=\left({\cfrac {\partial v^{i}}{\partial \xi ^{i}}}+v^{k}~\Gamma _{ik}^{i}\right)\\{\boldsymbol {\nabla }}\cdot {\boldsymbol {S}}&=\left({\cfrac {\partial S_{ik}}{\partial \xi _{i}}}-S_{lk}~\Gamma _{ii}^{l}-S_{il}~\Gamma _{ik}^{l}\right)~\mathbf {g} ^{k}\end{aligned}}}

Cylindrical polar coordinates

In cylindrical polar coordinates

∇

⋅

v

=

∂

v

r

∂

r

+

1

r

(

∂

v

θ

∂

θ

+

v

r

)

+

∂

v

z

∂

z

∇

⋅

S

=

∂

S

r

r

∂

r

e

r

+

∂

S

r

θ

∂

r

e

θ

+

∂

S

r

z

∂

r

e

z

+

1

r

[

∂

S

θ

r

∂

θ

+

(

S

r

r

−

S

θ

θ

)

]

e

r

+

1

r

[

∂

S

θ

θ

∂

θ

+

(

S

r

θ

+

S

θ

r

)

]

e

θ

+

1

r

[

∂

S

θ

z

∂

θ

+

S

r

z

]

e

z

+

∂

S

z

r

∂

z

e

r

+

∂

S

z

θ

∂

z

e

θ

+

∂

S

z

z

∂

z

e

z

{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}{\boldsymbol {\nabla }}\cdot \mathbf {v} =\quad &{\frac {\partial v_{r}}{\partial r}}+{\frac {1}{r}}\left({\frac {\partial v_{\theta }}{\partial \theta }}+v_{r}\right)+{\frac {\partial v_{z}}{\partial z}}\\{\boldsymbol {\nabla }}\cdot {\boldsymbol {S}}=\quad &{\frac {\partial S_{rr}}{\partial r}}~\mathbf {e} _{r}+{\frac {\partial S_{r\theta }}{\partial r}}~\mathbf {e} _{\theta }+{\frac {\partial S_{rz}}{\partial r}}~\mathbf {e} _{z}\\{}+{}&{\frac {1}{r}}\left[{\frac {\partial S_{\theta r}}{\partial \theta }}+(S_{rr}-S_{\theta \theta })\right]~\mathbf {e} _{r}+{\frac {1}{r}}\left[{\frac {\partial S_{\theta \theta }}{\partial \theta }}+(S_{r\theta }+S_{\theta r})\right]~\mathbf {e} _{\theta }+{\frac {1}{r}}\left[{\frac {\partial S_{\theta z}}{\partial \theta }}+S_{rz}\right]~\mathbf {e} _{z}\\{}+{}&{\frac {\partial S_{zr}}{\partial z}}~\mathbf {e} _{r}+{\frac {\partial S_{z\theta }}{\partial z}}~\mathbf {e} _{\theta }+{\frac {\partial S_{zz}}{\partial z}}~\mathbf {e} _{z}\end{aligned}}}

Curl of a tensor field

The curl of an order-n > 1 tensor field

T

(

x

)

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {T}}(\mathbf {x} )}

(

∇

×

T

)

⋅

c

=

∇

×

(

c

⋅

T

)

;

(

∇

×

v

)

⋅

c

=

∇

⋅

(

v

×

c

)

{\displaystyle ({\boldsymbol {\nabla }}\times {\boldsymbol {T}})\cdot \mathbf {c} ={\boldsymbol {\nabla }}\times (\mathbf {c} \cdot {\boldsymbol {T}})~;\qquad ({\boldsymbol {\nabla }}\times \mathbf {v} )\cdot \mathbf {c} ={\boldsymbol {\nabla }}\cdot (\mathbf {v} \times \mathbf {c} )}

where c is an arbitrary constant vector and v is a vector field.

Consider a vector field v and an arbitrary constant vector c . In index notation, the cross product is given by

v

×

c

=

ε

i

j

k

v

j

c

k

e

i

{\displaystyle \mathbf {v} \times \mathbf {c} =\varepsilon _{ijk}~v_{j}~c_{k}~\mathbf {e} _{i}}

where

ε

i

j

k

{\displaystyle \varepsilon _{ijk}}

permutation symbol , otherwise known as the Levi-Civita symbol. Then,

∇

⋅

(

v

×

c

)

=

ε

i

j

k

v

j

,

i

c

k

=

(

ε

i

j

k

v

j

,

i

e

k

)

⋅

c

=

(

∇

×

v

)

⋅

c

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {\nabla }}\cdot (\mathbf {v} \times \mathbf {c} )=\varepsilon _{ijk}~v_{j,i}~c_{k}=(\varepsilon _{ijk}~v_{j,i}~\mathbf {e} _{k})\cdot \mathbf {c} =({\boldsymbol {\nabla }}\times \mathbf {v} )\cdot \mathbf {c} }

Therefore,

∇

×

v

=

ε

i

j

k

v

j

,

i

e

k

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {\nabla }}\times \mathbf {v} =\varepsilon _{ijk}~v_{j,i}~\mathbf {e} _{k}}

Curl of a second-order tensor field

For a second-order tensor

S

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {S}}}

c

⋅

S

=

c

m

S

m

j

e

j

{\displaystyle \mathbf {c} \cdot {\boldsymbol {S}}=c_{m}~S_{mj}~\mathbf {e} _{j}}

Hence, using the definition of the curl of a first-order tensor field,

∇

×

(

c

⋅

S

)

=

ε

i

j

k

c

m

S

m

j

,

i

e

k

=

(

ε

i

j

k

S

m

j

,

i

e

k

⊗

e

m

)

⋅

c

=

(

∇

×

S

)

⋅

c

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {\nabla }}\times (\mathbf {c} \cdot {\boldsymbol {S}})=\varepsilon _{ijk}~c_{m}~S_{mj,i}~\mathbf {e} _{k}=(\varepsilon _{ijk}~S_{mj,i}~\mathbf {e} _{k}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{m})\cdot \mathbf {c} =({\boldsymbol {\nabla }}\times {\boldsymbol {S}})\cdot \mathbf {c} }

Therefore, we have

∇

×

S

=

ε

i

j

k

S

m

j

,

i

e

k

⊗

e

m

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {\nabla }}\times {\boldsymbol {S}}=\varepsilon _{ijk}~S_{mj,i}~\mathbf {e} _{k}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{m}}

Identities involving the curl of a tensor field

The most commonly used identity involving the curl of a tensor field,

T

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {T}}}

∇

×

(

∇

T

)

=

0

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {\nabla }}\times ({\boldsymbol {\nabla }}{\boldsymbol {T}})={\boldsymbol {0}}}

This identity holds for tensor fields of all orders. For the important case of a second-order tensor,

S

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {S}}}

∇

×

(

∇

S

)

=

0

⟹

S

m

i

,

j

−

S

m

j

,

i

=

0

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {\nabla }}\times ({\boldsymbol {\nabla }}{\boldsymbol {S}})={\boldsymbol {0}}\quad \implies \quad S_{mi,j}-S_{mj,i}=0}

Derivative of the determinant of a second-order tensor

The derivative of the determinant of a second order tensor

A

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {A}}}

∂

∂

A

det

(

A

)

=

det

(

A

)

[

A

−

1

]

T

.

{\displaystyle {\frac {\partial }{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}\det({\boldsymbol {A}})=\det({\boldsymbol {A}})~\left[{\boldsymbol {A}}^{-1}\right]^{\textsf {T}}~.}

In an orthonormal basis, the components of

A

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {A}}}

A . In that case, the right hand side corresponds the cofactors of the matrix.

Derivatives of the invariants of a second-order tensor

The principal invariants of a second order tensor are

I

1

(

A

)

=

tr

A

I

2

(

A

)

=

1

2

[

(

tr

A

)

2

−

tr

A

2

]

I

3

(

A

)

=

det

(

A

)

{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}I_{1}({\boldsymbol {A}})&={\text{tr}}{\boldsymbol {A}}\\I_{2}({\boldsymbol {A}})&={\frac {1}{2}}\left[({\text{tr}}{\boldsymbol {A}})^{2}-{\text{tr}}{{\boldsymbol {A}}^{2}}\right]\\I_{3}({\boldsymbol {A}})&=\det({\boldsymbol {A}})\end{aligned}}}

The derivatives of these three invariants with respect to

A

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {A}}}

∂

I

1

∂

A

=

1

∂

I

2

∂

A

=

I

1

1

−

A

T

∂

I

3

∂

A

=

det

(

A

)

[

A

−

1

]

T

=

I

2

1

−

A

T

(

I

1

1

−

A

T

)

=

(

A

2

−

I

1

A

+

I

2

1

)

T

{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}{\frac {\partial I_{1}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}&={\boldsymbol {\mathit {1}}}\\[3pt]{\frac {\partial I_{2}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}&=I_{1}~{\boldsymbol {\mathit {1}}}-{\boldsymbol {A}}^{\textsf {T}}\\[3pt]{\frac {\partial I_{3}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}&=\det({\boldsymbol {A}})~\left[{\boldsymbol {A}}^{-1}\right]^{\textsf {T}}=I_{2}~{\boldsymbol {\mathit {1}}}-{\boldsymbol {A}}^{\textsf {T}}~\left(I_{1}~{\boldsymbol {\mathit {1}}}-{\boldsymbol {A}}^{\textsf {T}}\right)=\left({\boldsymbol {A}}^{2}-I_{1}~{\boldsymbol {A}}+I_{2}~{\boldsymbol {\mathit {1}}}\right)^{\textsf {T}}\end{aligned}}}

Proof

From the derivative of the determinant we know that

∂

I

3

∂

A

=

det

(

A

)

[

A

−

1

]

T

.

{\displaystyle {\frac {\partial I_{3}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}=\det({\boldsymbol {A}})~\left[{\boldsymbol {A}}^{-1}\right]^{\textsf {T}}~.}

For the derivatives of the other two invariants, let us go back to the characteristic equation

det

(

λ

1

+

A

)

=

λ

3

+

I

1

(

A

)

λ

2

+

I

2

(

A

)

λ

+

I

3

(

A

)

.

{\displaystyle \det(\lambda ~{\boldsymbol {\mathit {1}}}+{\boldsymbol {A}})=\lambda ^{3}+I_{1}({\boldsymbol {A}})~\lambda ^{2}+I_{2}({\boldsymbol {A}})~\lambda +I_{3}({\boldsymbol {A}})~.}

Using the same approach as for the determinant of a tensor, we can show that

∂

∂

A

det

(

λ

1

+

A

)

=

det

(

λ

1

+

A

)

[

(

λ

1

+

A

)

−

1

]

T

.

{\displaystyle {\frac {\partial }{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}\det(\lambda ~{\boldsymbol {\mathit {1}}}+{\boldsymbol {A}})=\det(\lambda ~{\boldsymbol {\mathit {1}}}+{\boldsymbol {A}})~\left[(\lambda ~{\boldsymbol {\mathit {1}}}+{\boldsymbol {A}})^{-1}\right]^{\textsf {T}}~.}

Now the left hand side can be expanded as

∂

∂

A

det

(

λ

1

+

A

)

=

∂

∂

A

[

λ

3

+

I

1

(

A

)

λ

2

+

I

2

(

A

)

λ

+

I

3

(

A

)

]

=

∂

I

1

∂

A

λ

2

+

∂

I

2

∂

A

λ

+

∂

I

3

∂

A

.

{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}{\frac {\partial }{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}\det(\lambda ~{\boldsymbol {\mathit {1}}}+{\boldsymbol {A}})&={\frac {\partial }{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}\left[\lambda ^{3}+I_{1}({\boldsymbol {A}})~\lambda ^{2}+I_{2}({\boldsymbol {A}})~\lambda +I_{3}({\boldsymbol {A}})\right]\\&={\frac {\partial I_{1}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}~\lambda ^{2}+{\frac {\partial I_{2}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}~\lambda +{\frac {\partial I_{3}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}~.\end{aligned}}}

Hence

∂

I

1

∂

A

λ

2

+

∂

I

2

∂

A

λ

+

∂

I

3

∂

A

=

det

(

λ

1

+

A

)

[

(

λ

1

+

A

)

−

1

]

T

{\displaystyle {\frac {\partial I_{1}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}~\lambda ^{2}+{\frac {\partial I_{2}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}~\lambda +{\frac {\partial I_{3}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}=\det(\lambda ~{\boldsymbol {\mathit {1}}}+{\boldsymbol {A}})~\left[(\lambda ~{\boldsymbol {\mathit {1}}}+{\boldsymbol {A}})^{-1}\right]^{\textsf {T}}}

or,

(

λ

1

+

A

)

T

⋅

[

∂

I

1

∂

A

λ

2

+

∂

I

2

∂

A

λ

+

∂

I

3

∂

A

]

=

det

(

λ

1

+

A

)

1

.

{\displaystyle (\lambda ~{\boldsymbol {\mathit {1}}}+{\boldsymbol {A}})^{\textsf {T}}\cdot \left[{\frac {\partial I_{1}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}~\lambda ^{2}+{\frac {\partial I_{2}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}~\lambda +{\frac {\partial I_{3}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}\right]=\det(\lambda ~{\boldsymbol {\mathit {1}}}+{\boldsymbol {A}})~{\boldsymbol {\mathit {1}}}~.}

Expanding the right hand side and separating terms on the left hand side gives

(

λ

1

+

A

T

)

⋅

[

∂

I

1

∂

A

λ

2

+

∂

I

2

∂

A

λ

+

∂

I

3

∂

A

]

=

[

λ

3

+

I

1

λ

2

+

I

2

λ

+

I

3

]

1

{\displaystyle \left(\lambda ~{\boldsymbol {\mathit {1}}}+{\boldsymbol {A}}^{\textsf {T}}\right)\cdot \left[{\frac {\partial I_{1}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}~\lambda ^{2}+{\frac {\partial I_{2}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}~\lambda +{\frac {\partial I_{3}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}\right]=\left[\lambda ^{3}+I_{1}~\lambda ^{2}+I_{2}~\lambda +I_{3}\right]{\boldsymbol {\mathit {1}}}}

or,

[

∂

I

1

∂

A

λ

3

+

∂

I

2

∂

A

λ

2

+

∂

I

3

∂

A

λ

]

1

+

A

T

⋅

∂

I

1

∂

A

λ

2

+

A

T

⋅

∂

I

2

∂

A

λ

+

A

T

⋅

∂

I

3

∂

A

=

[

λ

3

+

I

1

λ

2

+

I

2

λ

+

I

3

]

1

.

{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\left[{\frac {\partial I_{1}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}~\lambda ^{3}\right.&\left.+{\frac {\partial I_{2}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}~\lambda ^{2}+{\frac {\partial I_{3}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}~\lambda \right]{\boldsymbol {\mathit {1}}}+{\boldsymbol {A}}^{\textsf {T}}\cdot {\frac {\partial I_{1}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}~\lambda ^{2}+{\boldsymbol {A}}^{\textsf {T}}\cdot {\frac {\partial I_{2}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}~\lambda +{\boldsymbol {A}}^{\textsf {T}}\cdot {\frac {\partial I_{3}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}\\&=\left[\lambda ^{3}+I_{1}~\lambda ^{2}+I_{2}~\lambda +I_{3}\right]{\boldsymbol {\mathit {1}}}~.\end{aligned}}}

If we define

I

0

:=

1

{\displaystyle I_{0}:=1}

I

4

:=

0

{\displaystyle I_{4}:=0}

[

∂

I

1

∂

A

λ

3

+

∂

I

2

∂

A

λ

2

+

∂

I

3

∂

A

λ

+

∂

I

4

∂

A

]

1

+

A

T

⋅

∂

I

0

∂

A

λ

3

+

A

T

⋅

∂

I

1

∂

A

λ

2

+

A

T

⋅

∂

I

2

∂

A

λ

+

A

T

⋅

∂

I

3

∂

A

=

[

I

0

λ

3

+

I

1

λ

2

+

I

2

λ

+

I

3

]

1

.

{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\left[{\frac {\partial I_{1}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}~\lambda ^{3}\right.&\left.+{\frac {\partial I_{2}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}~\lambda ^{2}+{\frac {\partial I_{3}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}~\lambda +{\frac {\partial I_{4}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}\right]{\boldsymbol {\mathit {1}}}+{\boldsymbol {A}}^{\textsf {T}}\cdot {\frac {\partial I_{0}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}~\lambda ^{3}+{\boldsymbol {A}}^{\textsf {T}}\cdot {\frac {\partial I_{1}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}~\lambda ^{2}+{\boldsymbol {A}}^{\textsf {T}}\cdot {\frac {\partial I_{2}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}~\lambda +{\boldsymbol {A}}^{\textsf {T}}\cdot {\frac {\partial I_{3}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}\\&=\left[I_{0}~\lambda ^{3}+I_{1}~\lambda ^{2}+I_{2}~\lambda +I_{3}\right]{\boldsymbol {\mathit {1}}}~.\end{aligned}}}

Collecting terms containing various powers of λ, we get

λ

3

(

I

0

1

−

∂

I

1

∂

A

1

−

A

T

⋅

∂

I

0

∂

A

)

+

λ

2

(

I

1

1

−

∂

I

2

∂

A

1

−

A

T

⋅

∂

I

1

∂

A

)

+

λ

(

I

2

1

−

∂

I

3

∂

A

1

−

A

T

⋅

∂

I

2

∂

A

)

+

(

I

3

1

−

∂

I

4

∂

A

1

−

A

T

⋅

∂

I

3

∂

A

)

=

0

.

{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\lambda ^{3}&\left(I_{0}~{\boldsymbol {\mathit {1}}}-{\frac {\partial I_{1}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}~{\boldsymbol {\mathit {1}}}-{\boldsymbol {A}}^{\textsf {T}}\cdot {\frac {\partial I_{0}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}\right)+\lambda ^{2}\left(I_{1}~{\boldsymbol {\mathit {1}}}-{\frac {\partial I_{2}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}~{\boldsymbol {\mathit {1}}}-{\boldsymbol {A}}^{\textsf {T}}\cdot {\frac {\partial I_{1}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}\right)+\\&\qquad \qquad \lambda \left(I_{2}~{\boldsymbol {\mathit {1}}}-{\frac {\partial I_{3}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}~{\boldsymbol {\mathit {1}}}-{\boldsymbol {A}}^{\textsf {T}}\cdot {\frac {\partial I_{2}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}\right)+\left(I_{3}~{\boldsymbol {\mathit {1}}}-{\frac {\partial I_{4}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}~{\boldsymbol {\mathit {1}}}-{\boldsymbol {A}}^{\textsf {T}}\cdot {\frac {\partial I_{3}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}\right)=0~.\end{aligned}}}

Then, invoking the arbitrariness of λ, we have

I

0

1

−

∂

I

1

∂

A

1

−

A

T

⋅

∂

I

0

∂

A

=

0

I

1

1

−

∂

I

2

∂

A

1

−

I

2

1

−

∂

I

3

∂

A

1

−

A

T

⋅

∂

I

2

∂

A

=

0

I

3

1

−

∂

I

4

∂

A

1

−

A

T

⋅

∂

I

3

∂

A

=

0

.

{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}I_{0}~{\boldsymbol {\mathit {1}}}-{\frac {\partial I_{1}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}~{\boldsymbol {\mathit {1}}}-{\boldsymbol {A}}^{\textsf {T}}\cdot {\frac {\partial I_{0}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}&=0\\I_{1}~{\boldsymbol {\mathit {1}}}-{\frac {\partial I_{2}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}~{\boldsymbol {\mathit {1}}}-I_{2}~{\boldsymbol {\mathit {1}}}-{\frac {\partial I_{3}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}~{\boldsymbol {\mathit {1}}}-{\boldsymbol {A}}^{\textsf {T}}\cdot {\frac {\partial I_{2}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}&=0\\I_{3}~{\boldsymbol {\mathit {1}}}-{\frac {\partial I_{4}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}~{\boldsymbol {\mathit {1}}}-{\boldsymbol {A}}^{\textsf {T}}\cdot {\frac {\partial I_{3}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}&=0~.\end{aligned}}}

This implies that

∂

I

1

∂

A

=

1

∂

I

2

∂

A

=

I

1

1

−

A

T

∂

I

3

∂

A

=

I

2

1

−

A

T

(

I

1

1

−

A

T

)

=

(

A

2

−

I

1

A

+

I

2

1

)

T

{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}{\frac {\partial I_{1}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}&={\boldsymbol {\mathit {1}}}\\{\frac {\partial I_{2}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}&=I_{1}~{\boldsymbol {\mathit {1}}}-{\boldsymbol {A}}^{\textsf {T}}\\{\frac {\partial I_{3}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}&=I_{2}~{\boldsymbol {\mathit {1}}}-{\boldsymbol {A}}^{\textsf {T}}~\left(I_{1}~{\boldsymbol {\mathit {1}}}-{\boldsymbol {A}}^{\textsf {T}}\right)=\left({\boldsymbol {A}}^{2}-I_{1}~{\boldsymbol {A}}+I_{2}~{\boldsymbol {\mathit {1}}}\right)^{\textsf {T}}\end{aligned}}}

Derivative of the second-order identity tensor

Let

1

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {\mathit {1}}}}

A

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {A}}}

∂

1

∂

A

:

T

=

0

:

T

=

0

{\displaystyle {\frac {\partial {\boldsymbol {\mathit {1}}}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}:{\boldsymbol {T}}={\boldsymbol {\mathsf {0}}}:{\boldsymbol {T}}={\boldsymbol {\mathit {0}}}}

This is because

1

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {\mathit {1}}}}

A

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {A}}}

Derivative of a second-order tensor with respect to itself

Let

A

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {A}}}

∂

A

∂

A

:

T

=

[

∂

∂

α

(

A

+

α

T

)

]

α

=

0

=

T

=

I

:

T

{\displaystyle {\frac {\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}:{\boldsymbol {T}}=\left[{\frac {\partial }{\partial \alpha }}({\boldsymbol {A}}+\alpha ~{\boldsymbol {T}})\right]_{\alpha =0}={\boldsymbol {T}}={\boldsymbol {\mathsf {I}}}:{\boldsymbol {T}}}

Therefore,

∂

A

∂

A

=

I

{\displaystyle {\frac {\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}={\boldsymbol {\mathsf {I}}}}

Here

I

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {\mathsf {I}}}}

I

=

δ

i

k

δ

j

l

e

i

⊗

e

j

⊗

e

k

⊗

e

l

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {\mathsf {I}}}=\delta _{ik}~\delta _{jl}~\mathbf {e} _{i}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{j}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{k}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{l}}

This result implies that

∂

A

T

∂

A

:

T

=

I

T

:

T

=

T

T

{\displaystyle {\frac {\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}^{\textsf {T}}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}:{\boldsymbol {T}}={\boldsymbol {\mathsf {I}}}^{\textsf {T}}:{\boldsymbol {T}}={\boldsymbol {T}}^{\textsf {T}}}

where

I

T

=

δ

j

k

δ

i

l

e

i

⊗

e

j

⊗

e

k

⊗

e

l

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {\mathsf {I}}}^{\textsf {T}}=\delta _{jk}~\delta _{il}~\mathbf {e} _{i}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{j}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{k}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{l}}

Therefore, if the tensor

A

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {A}}}

∂

A

∂

A

=

I

(

s

)

=

1

2

(

I

+

I

T

)

{\displaystyle {\frac {\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}={\boldsymbol {\mathsf {I}}}^{(s)}={\frac {1}{2}}~\left({\boldsymbol {\mathsf {I}}}+{\boldsymbol {\mathsf {I}}}^{\textsf {T}}\right)}

where the symmetric fourth order identity tensor is

I

(

s

)

=

1

2

(

δ

i

k

δ

j

l

+

δ

i

l

δ

j

k

)

e

i

⊗

e

j

⊗

e

k

⊗

e

l

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {\mathsf {I}}}^{(s)}={\frac {1}{2}}~(\delta _{ik}~\delta _{jl}+\delta _{il}~\delta _{jk})~\mathbf {e} _{i}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{j}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{k}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{l}}

Derivative of the inverse of a second-order tensor

Let

A

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {A}}}

T

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {T}}}

∂

∂

A

(

A

−

1

)

:

T

=

−

A

−

1

⋅

T

⋅

A

−

1

{\displaystyle {\frac {\partial }{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}\left({\boldsymbol {A}}^{-1}\right):{\boldsymbol {T}}=-{\boldsymbol {A}}^{-1}\cdot {\boldsymbol {T}}\cdot {\boldsymbol {A}}^{-1}}

In index notation with respect to an orthonormal basis

∂

A

i

j

−

1

∂

A

k

l

T

k

l

=

−

A

i

k

−

1

T

k

l

A

l

j

−

1

⟹

∂

A

i

j

−

1

∂

A

k

l

=

−

A

i

k

−

1

A

l

j

−

1

{\displaystyle {\frac {\partial A_{ij}^{-1}}{\partial A_{kl}}}~T_{kl}=-A_{ik}^{-1}~T_{kl}~A_{lj}^{-1}\implies {\frac {\partial A_{ij}^{-1}}{\partial A_{kl}}}=-A_{ik}^{-1}~A_{lj}^{-1}}

We also have

∂

∂

A

(

A

−

T

)

:

T

=

−

A

−

T

⋅

T

T

⋅

A

−

T

{\displaystyle {\frac {\partial }{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}\left({\boldsymbol {A}}^{-{\textsf {T}}}\right):{\boldsymbol {T}}=-{\boldsymbol {A}}^{-{\textsf {T}}}\cdot {\boldsymbol {T}}^{\textsf {T}}\cdot {\boldsymbol {A}}^{-{\textsf {T}}}}

In index notation

∂

A

j

i

−

1

∂

A

k

l

T

k

l

=

−

A

j

k

−

1

T

l

k

A

l

i

−

1

⟹

∂

A

j

i

−

1

∂

A

k

l

=

−

A

l

i

−

1

A

j

k

−

1

{\displaystyle {\frac {\partial A_{ji}^{-1}}{\partial A_{kl}}}~T_{kl}=-A_{jk}^{-1}~T_{lk}~A_{li}^{-1}\implies {\frac {\partial A_{ji}^{-1}}{\partial A_{kl}}}=-A_{li}^{-1}~A_{jk}^{-1}}

If the tensor

A

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {A}}}

∂

A

i

j

−

1

∂

A

k

l

=

−

1

2

(

A

i

k

−

1

A

j

l

−

1

+

A

i

l

−

1

A

j

k

−

1

)

{\displaystyle {\frac {\partial A_{ij}^{-1}}{\partial A_{kl}}}=-{\cfrac {1}{2}}\left(A_{ik}^{-1}~A_{jl}^{-1}+A_{il}^{-1}~A_{jk}^{-1}\right)}

Proof

Recall that

∂

1

∂

A

:

T

=

0

{\displaystyle {\frac {\partial {\boldsymbol {\mathit {1}}}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}:{\boldsymbol {T}}={\boldsymbol {\mathit {0}}}}

Since

A

−

1

⋅

A

=

1

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {A}}^{-1}\cdot {\boldsymbol {A}}={\boldsymbol {\mathit {1}}}}

∂

∂

A

(

A

−

1

⋅

A

)

:

T

=

0

{\displaystyle {\frac {\partial }{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}\left({\boldsymbol {A}}^{-1}\cdot {\boldsymbol {A}}\right):{\boldsymbol {T}}={\boldsymbol {\mathit {0}}}}

Using the product rule for second order tensors

∂

∂

S

[

F

1

(

S

)

⋅

F

2

(

S

)

]

:

T

=

(

∂

F

1

∂

S

:

T

)

⋅

F

2

+

F

1

⋅

(

∂

F

2

∂

S

:

T

)

{\displaystyle {\frac {\partial }{\partial {\boldsymbol {S}}}}[{\boldsymbol {F}}_{1}({\boldsymbol {S}})\cdot {\boldsymbol {F}}_{2}({\boldsymbol {S}})]:{\boldsymbol {T}}=\left({\frac {\partial {\boldsymbol {F}}_{1}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {S}}}}:{\boldsymbol {T}}\right)\cdot {\boldsymbol {F}}_{2}+{\boldsymbol {F}}_{1}\cdot \left({\frac {\partial {\boldsymbol {F}}_{2}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {S}}}}:{\boldsymbol {T}}\right)}

we get

∂

∂

A

(

A

−

1

⋅

A

)

:

T

=

(

∂

A

−

1

∂

A

:

T

)

⋅

A

+

A

−

1

⋅

(

∂

A

∂

A

:

T

)

=

0

{\displaystyle {\frac {\partial }{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}({\boldsymbol {A}}^{-1}\cdot {\boldsymbol {A}}):{\boldsymbol {T}}=\left({\frac {\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}^{-1}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}:{\boldsymbol {T}}\right)\cdot {\boldsymbol {A}}+{\boldsymbol {A}}^{-1}\cdot \left({\frac {\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}:{\boldsymbol {T}}\right)={\boldsymbol {\mathit {0}}}}

or,

(

∂

A

−

1

∂

A

:

T

)

⋅

A

=

−

A

−

1

⋅

T

{\displaystyle \left({\frac {\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}^{-1}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}:{\boldsymbol {T}}\right)\cdot {\boldsymbol {A}}=-{\boldsymbol {A}}^{-1}\cdot {\boldsymbol {T}}}

Therefore,

∂

∂

A

(

A

−

1

)

:

T

=

−

A

−

1

⋅

T

⋅

A

−

1

{\displaystyle {\frac {\partial }{\partial {\boldsymbol {A}}}}\left({\boldsymbol {A}}^{-1}\right):{\boldsymbol {T}}=-{\boldsymbol {A}}^{-1}\cdot {\boldsymbol {T}}\cdot {\boldsymbol {A}}^{-1}}

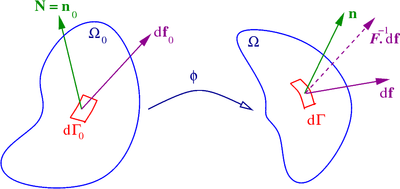

Integration by parts

Domain

Ω

{\displaystyle \Omega }

Γ

{\displaystyle \Gamma }

n

{\displaystyle \mathbf {n} }

Another important operation related to tensor derivatives in continuum mechanics is integration by parts. The formula for integration by parts can be written as

∫

Ω

F

⊗

∇

G

d

Ω

=

∫

Γ

n

⊗

(

F

⊗

G

)

d

Γ

−

∫

Ω

G

⊗

∇

F

d

Ω

{\displaystyle \int _{\Omega }{\boldsymbol {F}}\otimes {\boldsymbol {\nabla }}{\boldsymbol {G}}\,{\rm {d}}\Omega =\int _{\Gamma }\mathbf {n} \otimes ({\boldsymbol {F}}\otimes {\boldsymbol {G}})\,{\rm {d}}\Gamma -\int _{\Omega }{\boldsymbol {G}}\otimes {\boldsymbol {\nabla }}{\boldsymbol {F}}\,{\rm {d}}\Omega }

where

F

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {F}}}

G

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {G}}}

n

{\displaystyle \mathbf {n} }

⊗

{\displaystyle \otimes }

∇

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {\nabla }}}

F

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {F}}}

divergence theorem

∫

Ω

∇

G

d

Ω

=

∫

Γ

n

⊗

G

d

Γ

.

{\displaystyle \int _{\Omega }{\boldsymbol {\nabla }}{\boldsymbol {G}}\,{\rm {d}}\Omega =\int _{\Gamma }\mathbf {n} \otimes {\boldsymbol {G}}\,{\rm {d}}\Gamma \,.}

We can express the formula for integration by parts in Cartesian index notation as

∫

Ω

F

i

j

k

.

.

.

.

G

l

m

n

.

.

.

,

p

d

Ω

=

∫

Γ

n

p

F

i

j

k

.

.

.

G

l

m

n

.

.

.

d

Γ

−

∫

Ω

G

l

m

n

.

.

.

F

i

j

k

.

.

.

,

p

d

Ω

.

{\displaystyle \int _{\Omega }F_{ijk....}\,G_{lmn...,p}\,{\rm {d}}\Omega =\int _{\Gamma }n_{p}\,F_{ijk...}\,G_{lmn...}\,{\rm {d}}\Gamma -\int _{\Omega }G_{lmn...}\,F_{ijk...,p}\,{\rm {d}}\Omega \,.}

For the special case where the tensor product operation is a contraction of one index and the gradient operation is a divergence, and both

F

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {F}}}

G

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {G}}}

∫

Ω

F

⋅

(

∇

⋅

G

)

d

Ω

=

∫

Γ

n

⋅

(

G

⋅

F

T

)

d

Γ

−

∫

Ω

(

∇

F

)

:

G

T

d

Ω

.

{\displaystyle \int _{\Omega }{\boldsymbol {F}}\cdot ({\boldsymbol {\nabla }}\cdot {\boldsymbol {G}})\,{\rm {d}}\Omega =\int _{\Gamma }\mathbf {n} \cdot \left({\boldsymbol {G}}\cdot {\boldsymbol {F}}^{\textsf {T}}\right)\,{\rm {d}}\Gamma -\int _{\Omega }({\boldsymbol {\nabla }}{\boldsymbol {F}}):{\boldsymbol {G}}^{\textsf {T}}\,{\rm {d}}\Omega \,.}

In index notation,

∫

Ω

F

i

j

G

p

j

,

p

d

Ω

=

∫

Γ

n

p

F

i

j

G

p

j

d

Γ

−

∫

Ω

G

p

j

F

i

j

,

p

d

Ω

.

{\displaystyle \int _{\Omega }F_{ij}\,G_{pj,p}\,{\rm {d}}\Omega =\int _{\Gamma }n_{p}\,F_{ij}\,G_{pj}\,{\rm {d}}\Gamma -\int _{\Omega }G_{pj}\,F_{ij,p}\,{\rm {d}}\Omega \,.}

See also

References

^ J. C. Simo and T. J. R. Hughes, 1998, Computational Inelasticity , Springer

^ J. E. Marsden and T. J. R. Hughes, 2000, Mathematical Foundations of Elasticity , Dover.

^ Ogden, R. W., 2000, Nonlinear Elastic Deformations , Dover.

^ http://homepages.engineering.auckland.ac.nz/~pkel015/SolidMechanicsBooks/Part_III/Chapter_1_Vectors_Tensors/Vectors_Tensors_14_Tensor_Calculus.pdf ^ a b Hjelmstad, Keith (2004). Fundamentals of Structural Mechanics . Springer Science & Business Media. p. 45. ISBN 9780387233307

![{\displaystyle {\frac {\partial f}{\partial \mathbf {v} }}\cdot \mathbf {u} =Df(\mathbf {v} )[\mathbf {u} ]=\left[{\frac {\rm {d}}{{\rm {d}}\alpha }}~f(\mathbf {v} +\alpha ~\mathbf {u} )\right]_{\alpha =0}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/1cd4359c84cf58e41375f33503df17f688456372)

![{\displaystyle {\frac {\partial \mathbf {f} }{\partial \mathbf {v} }}\cdot \mathbf {u} =D\mathbf {f} (\mathbf {v} )[\mathbf {u} ]=\left[{\frac {\rm {d}}{{\rm {d}}\alpha }}~\mathbf {f} (\mathbf {v} +\alpha ~\mathbf {u} )\right]_{\alpha =0}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c9b946f4d0b2712f1f6b890f4b5b45a2bb70b7c7)

![{\displaystyle {\frac {\partial f}{\partial {\boldsymbol {S}}}}:{\boldsymbol {T}}=Df({\boldsymbol {S}})[{\boldsymbol {T}}]=\left[{\frac {\rm {d}}{{\rm {d}}\alpha }}~f({\boldsymbol {S}}+\alpha ~{\boldsymbol {T}})\right]_{\alpha =0}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/b97c637955623ac4900c4f80d6ea1bdef354076a)

![{\displaystyle {\frac {\partial {\boldsymbol {F}}}{\partial {\boldsymbol {S}}}}:{\boldsymbol {T}}=D{\boldsymbol {F}}({\boldsymbol {S}})[{\boldsymbol {T}}]=\left[{\frac {\rm {d}}{{\rm {d}}\alpha }}~{\boldsymbol {F}}({\boldsymbol {S}}+\alpha ~{\boldsymbol {T}})\right]_{\alpha =0}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/32c53f2457fa27a03ca72cbd48debb1255593088)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}{\boldsymbol {\nabla }}{\boldsymbol {T}}\cdot \mathbf {c} &=\left.{\cfrac {\rm {d}}{{\rm {d}}\alpha }}~{\boldsymbol {T}}(x_{1}+\alpha c_{1},x_{2}+\alpha c_{2},x_{3}+\alpha c_{3})\right|_{\alpha =0}\equiv \left.{\cfrac {\rm {d}}{{\rm {d}}\alpha }}~{\boldsymbol {T}}(y_{1},y_{2},y_{3})\right|_{\alpha =0}\\&=\left[{\cfrac {\partial {\boldsymbol {T}}}{\partial y_{1}}}~{\cfrac {\partial y_{1}}{\partial \alpha }}+{\cfrac {\partial {\boldsymbol {T}}}{\partial y_{2}}}~{\cfrac {\partial y_{2}}{\partial \alpha }}+{\cfrac {\partial {\boldsymbol {T}}}{\partial y_{3}}}~{\cfrac {\partial y_{3}}{\partial \alpha }}\right]_{\alpha =0}=\left[{\cfrac {\partial {\boldsymbol {T}}}{\partial y_{1}}}~c_{1}+{\cfrac {\partial {\boldsymbol {T}}}{\partial y_{2}}}~c_{2}+{\cfrac {\partial {\boldsymbol {T}}}{\partial y_{3}}}~c_{3}\right]_{\alpha =0}\\&={\cfrac {\partial {\boldsymbol {T}}}{\partial x_{1}}}~c_{1}+{\cfrac {\partial {\boldsymbol {T}}}{\partial x_{2}}}~c_{2}+{\cfrac {\partial {\boldsymbol {T}}}{\partial x_{3}}}~c_{3}\equiv {\cfrac {\partial {\boldsymbol {T}}}{\partial x_{i}}}~c_{i}={\cfrac {\partial {\boldsymbol {T}}}{\partial x_{i}}}~(\mathbf {e} _{i}\cdot \mathbf {c} )=\left[{\cfrac {\partial {\boldsymbol {T}}}{\partial x_{i}}}\otimes \mathbf {e} _{i}\right]\cdot \mathbf {c} \qquad \square \end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9a0f6d278fcbf035df564ec347a8b535989d49a5)