Charles Biro

| Charles Biro | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | May 12, 1911 New York |

| Died | March 4, 1972 (aged 60) |

| Nationality | American |

| Area(s) | Cartoonist, Writer, Penciller, Editor |

Notable works | Airboy Crime Does Not Pay Daredevil Comics |

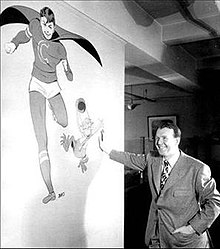

Charles Biro (May 12, 1911 – March 4, 1972) was an American comic book creator and cartoonist. He is today chiefly known for creating the comic book characters Airboy and Steel Sterling, and for his work at Lev Gleason Publications on Daredevil Comics and Crime Does Not Pay.

Biography

A New York native, Charles Biro graduated from Stuyvesant High School before studying art at the Brooklyn Museum School of Art and the Grand Central School of Art.[1] He joined the Harry "A" Chesler Shop c. 1936.[2] Working in the multiple roles of writer, artist and later supervisor at one of the earliest comics packaging art studios, Biro moved from the Chesler Shop in 1939 to take up similar roles at MLJ Comics.[2]

Biro worked as artistic supervisor (as well as writer and artist) for MLJ until 1941, writing and drawing such characters as Steel Sterling (a character he created)[3] and Sgt. Boyle, before moving to Lev Gleason Publications, for whom he would work for the next 15 years.[2]

While working for Gleason, Biro held the roles of editorial director, head writer and cover artist.[2] According to comics historians Jerry Bails and Hames Ware, Biro did not do much, if any, interior artwork after 1942, focusing solely on covers.[2]

For Gleason, he produced a number of titles, among them (with Bob Wood) Chuck "Crimebuster" Chandler, who appeared in Boy Comics (1942–1956).[3][4] Chandler is described by Joe Brancatelli as "a hero, yes, but first a boy... arguably the best-handled boy's adventure feature ever to appear in comics."[3] Later, he marketed "the first full adult comic book, Tops, a 1949 experiment in full color and standard magazine size" (which lasted two issues, July and September 1949).[3]

Daredevil

Although Biro's most important work for Gleason was arguably in the nascent genre of crime comics (below), he is perhaps more widely known, however, for his lengthy work on one of Gleason's longest-running titles, producing a landmark run on the first hero to take the name Daredevil (no relation to the Marvel Comics character of the same name). Although primarily by this point in his career a writer and cover artist, Biro drew much of the first issue of Daredevil Comics (the character had launched in the pages of Silver Streak #6 (September 1940)) titled Daredevil Battles Hitler #1 (July 1941). Biro would stay with the title for the rest of his time working for Gleason, and make the character one of the most acclaimed of the Golden Age. The title is described as:

an above-average Golden Age superhero title from quality-conscious Lev Gleason Publishing [which under the guidance of writer-artist Charles Biro... evolved into a costume-hero venue for a variety of comics stories.[5]

Joe Brancatelli, in Maurice Horn's The World Encyclopedia of Comics (2nd ed.) described the pre-Biro Daredevil as "Gleason's top seller and a fine superhero concept in its own right... created by Don Rico and Jack Binder", swiftly taken over by Biro, who then performed a "miraculous job" with the title, through which his "real talent became known."[3] The Lambiek Comiclopedia similarly calls Biro's "guiding of 'Daredevil'" "[o]ne of his most impressive feats."[6]

Biro was joined by writer-artist Basil Wolverton and Dick Briefer in Daredevil Comics.[5] In issue #13 (October 1942) Biro introduced the "Little Wise Guys," echoing such junior characters as the Jack Kirby-created Newsboy Legion for DC Comics. The Wise Guys comprised Curly, Jocko, Peewee, Scarecrow and Meatball, with Meatball meeting an early death—"a rare moment in comics of the days."[5] By the late 1940s, with superheroes going out of fashion, the Little Wise Guys took center stage, and "Daredevil unmasked and became a mentor to the kids, who eventually pushed the title character out of his own comic book."[5] After writing the adventures of Daredevil between 1941 and 1950, with issue #70 (January 1950), Biro continued to write "Little Wise Guys" stories until the series ended with issue #134 (September 1956).[2]

Other work

Among his work for other companies, was the comic strip Goodbyland in 1938, and "Block & Fall" for Centaur Comics (1938).[2] He produced work for Henle and Fiction House in the mid to late 1930s and co-created the character of Airboy for Hillman Periodicals in 1941. Debuting in the second issue of Air Fighters Comics (November 1942), Airboy (with artist Al Camy and scripter Dick Wood) was to be one of Biro's most enduring creations, and has been resurrected several times since the character's demise (with Hillman) in 1953, after a run of over 100 issues, during which time Air Fighters Comics was renamed Airboy Comics (December 1945).[7]

In October 1955, he wrote and illustrated the first of around 13[8] issues of a weekly humor book entitled Poppo of the Popcorn Theatre for Fuller, which was "virtually ignored."[3]

Legacy

Crime comics

For Lev Gleason, Biro helped to create the Crime comics genre with the landmark title Crime Does Not Pay (1942–1955), which he edited along with Bob Wood.[9] The title had an instant effect on the marketplace, and is described in The Comic Buyer's Guide Standard Catalog of Comic Books as "the comic book that got the entire crime comics genre rolling—and may have unwittingly contributed to the formation of the Comics Code years later."[9]

"Usually regarded as the comic book industry's first crime title," the series started with Crime Does Not Pay #22 (July 1942), carrying on the numbering from Silver Streak Comics #21.[3] The landmark title was the result of bar talk between Biro and Wood (both alumni of the Harry "A" Chesler Shop[10]), who worked together regularly.[9]

It began when Bob Wood and Charles Biro were swapping yarns in a bar and decided that gangsters and criminals would provide a neverending flow of new stories for a comic book. Grabbing the name from a popular series of MGM live-action shorts of the 1930s, the pair conspired to rename Silver Streak to Crime Does Not Pay...[9]

Part of "the allure of the series" was due to Biro's narrator, "Mr. Crime" (a prototype for the more famous EC Comics "GhouLunatic" trio).[9]

The series immediately spawned a plethora of imitators, but "[t]hroughout its run, Crime Does Not Pay was always the best-written, best-illustrated, and best-edited crime title, and it was always the best-selling title, as well."[3] Although it can arguably be said to have been a major factor in the comics witchhunts of the 1950s, it is fair to note that it stood apart from its more tawdry imitators:

Although its imitators were gory and excessive, and eventually brought on a ruinous round of censorship of comics, the stellar title was the last book to succumb.[3]

Indeed, Brancatelli claims that "for several years during the late 1940s and early 1950s, Boy, Daredevil and Crime Does Not Pay [all Biro-edited and -written titles, largely under Biro covers] were the three best-selling titles in a comic field of over 400 competitors."[3]

Later life and career

After parting company with Gleason in 1956, Biro "left the field for television,"[3] moving into the field of graphic design. He was employed for the last ten years of his life by NBC as a graphic artist between 1962 and 1972.[2] During the late 1960s, he became curious about a comic book convention and walked from NBC over to the convention hotel. When convention staffers realized who he was, he was handed a microphone and spoke spontaneously about his career for 20 minutes.

He died on 4 March 1972, and was nominated for induction into the Eisner Hall of Fame in both 1998 and 2000, before being formally inducted in 2002.

Quotes

Joe Brancatelli:

If Jack Kirby was the most important artistic force in comics during the 1940s, Biro certainly proved to be the finest editor and writer. While others were providing escapist fantasy in their comic books, Charles Biro decided his books would be different and better. He even dubbed them 'Illustories,' but the name never caught on. Throughough his 16-year stint as editorial director and chief writer at Lev Gleason, Biro proved to be the most innovative and certainly most advanced writer in the comic book field.[3]

References

- ^ Dakin, Brett (2020). American Daredevil. Chapterhouse Comics. p. 19.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Bails, Jerry G. and Hames Ware (ed.s), The Who's Who of American Comic Books: Volume One, p. 31 (Bails, 1973)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Brancatelli, Joe "Biro, Charles (1911-1972)" in Maurice Horn (ed.), The World Encyclopedia of Comics (Chelsea House Publishers, 2nd ed., 1999) ISBN 0-7910-4854-3, pp. 134-135

- ^ [1]

- ^ a b c d Miller, J. J., Thompson, Maggie, Peter Bickford and Frankenhoff, Brent, The Comic Buyer's Guide Standard Catalog of Comic Books, 4th Edition (KP Books, 2005) - "Daredevil", pp. 385-386 [Standard Guide text by Rob Salkowitz]

- ^ Charles Biro at Lambiek's Comiclopedia. Accessed August 29, 2008

- ^ Miller, J. J., Thompson, Maggie, Peter Bickford and Frankenhoff, Brent, The Comic Buyer's Guide Standard Catalog of Comic Books, 4th Edition (KP Books, 2005) - "Airboy Comics"; "Air Fighters Comics", pp. 68-69

- ^ The 13th issue of Poppo (released in the third week of January, 1956) is thought to be the final issue, as per: Miller, J. J., Thompson, Maggie, Peter Bickford and Frankenhoff, Brent, The Comic Buyer's Guide Standard Catalog of Comic Books, 4th Edition (KP Books, 2005) - "Poppo of the Popcorn Theatre", p. 1066

- ^ a b c d e Miller, J. J., Thompson, Maggie, Peter Bickford and Frankenhoff, Brent, The Comic Buyer's Guide Standard Catalog of Comic Books, 4th Edition (KP Books, 2005) - "Crime Does Not Pay", pp. 366-367

- ^ Nicky Wright "Seducers of the Innocent". Accessed August 29, 2008

Sources

- Strickler, Dave. Syndicated Comic Strips and Artists, 1924-1995: The Complete Index. Cambria, California: Comics Access, 1995. ISBN 0-9700077-0-1

- Comiclopedia: Charles Biro