2011 Mississippi River floods

100 populated locations were experiencing major or moderate flooding on May 8, 2011. Source: National Weather Service | |

| Date | May 4, 2011 to June 20, 2011 |

|---|---|

| Location | Mississippi River Valley, United States |

| Deaths | About 20 direct 348 indirect from preceding storms[1][2][3] |

| Property damage | US$2 to 4 billion[4][5] |

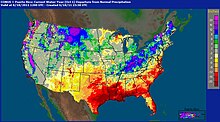

The Mississippi River floods in April and May 2011 were among the largest and most damaging recorded along the U.S. waterway in the past century, comparable in extent to the major floods of 1927 and 1993. In April 2011, two major storm systems deposited record levels of rainfall on the Mississippi River watershed. When that additional water combined with the springtime snowmelt, the river and many of its tributaries began to swell to record levels by the beginning of May. Areas along the Mississippi itself experiencing flooding included Illinois, Missouri, Kentucky, Tennessee, Arkansas, Mississippi, and Louisiana.

U.S. President Barack Obama declared the western counties of Kentucky, Tennessee, and Mississippi federal disaster areas.[6] For the first time in 37 years, the Morganza Spillway was opened on May 14, deliberately flooding 4,600 square miles (12,000 km2) of rural Louisiana to save most of Baton Rouge and New Orleans.[7]

Fourteen people were killed in Arkansas,[8] with 348 killed across seven states in the preceding storms.[1][2][3] Thousands of homes were ordered evacuated, including over 1,300 in Memphis,[9] and more than 24,500 in Louisiana and Mississippi,[10][11] though some people disregarded mandatory evacuation orders.[12] The flood crested in Memphis on May 10 and artificially crested in southern Louisiana on May 15, a week earlier than it would have if spillways had not been opened.[13] The United States Army Corps of Engineers stated that an area in Louisiana between Simmesport and Baton Rouge was expected to be inundated with 20–30 feet (6.1–9.1 m) of water.[14] Baton Rouge, New Orleans, and many other river towns were threatened,[15][16] but officials stressed that they should be able to avoid catastrophic flooding.[17]

From April 14–16, the storm system responsible for one of the largest tornado outbreaks in U.S. history also produced large amounts of rainfall across the southern and midwestern United States. Two more storm systems, each with heavy rain and tornadoes, hit in the third week of April. In the fourth week of April, from April 25–28, another, even more extensive and deadly storm system passed through the Mississippi Valley dumping more rainfall resulting in deadly flash floods.[18] The unprecedented extensive rainfall from these four storms, combined with springtime snow melt from the Upper Midwest, created the perfect situation for a 500-year flood along the Mississippi.

Flood stages and effects by state

As flood waters proceeded down the Lower Mississippi from the St. Louis area (where the Missouri River and the Mississippi River converge), they affected Missouri and Illinois, then Tennessee, Arkansas, Mississippi, and Louisiana.

Missouri and Illinois

On May 3, using the planned procedures for the Birds Point-New Madrid Floodway, the Corps of Engineers blasted a two-mile (3 km) hole in the levee protecting the floodway, flooding 130,000 acres (530 km2) of farmland in Mississippi County, Missouri, in an effort to save the town of Cairo, Illinois and the rest of the levee system, from record-breaking flood waters.[19] The breach displaced around 200 residents of Missouri's Mississippi and New Madrid counties, who were forced to evacuate after a court approved the plan to breach the levee.[20]

Tennessee

Dyersburg, a city in northwestern Tennessee, experienced the worst flooding with over 600 homes and businesses inundated as the Forked Deer River, a tributary of the Mississippi, flowed backwards into southern areas of the city.[21] On May 10, the river reached 47.8 feet (14.6 m), the highest level reached at Memphis since 1937, when the river there reached a record 48.7 feet (14.8 m), and the second highest level ever recorded, even surpassing the 1927 flood. Many local rivers spilled their banks, including Big Creek, the Loosahatchie River, and the Wolf River along with Nonconnah Creek. Subsequent flooding occurred in Millington, as well as suburban areas of Frayser, Bartlett, and East Memphis.

Arkansas

Interstate 40, connecting Memphis and Little Rock, experienced flooding west of Memphis along the White River between Hazen and Brinkley, where lanes in both directions were closed. Brinkley itself also experienced flooding. Eight people died in Arkansas as a result of flooding.[22]

Mississippi

This section's factual accuracy may be compromised due to out-of-date information. (February 2012) |

In Tunica County, nine casinos located on stationary river barges were closed most of May. The hotel portion of the casinos are located on adjacent, low-lying land, and began to flood with the rising waters, some up to 6 feet.[23] Near Vicksburg, Highway 465 in Warren and Issaquena counties was closed on May 3 due to high flood waters.[24] North-south access to and from Vicksburg was cut off for more than two weeks. U.S. Highway 61 between Vicksburg and Port Gibson was closed by backwater flooding along the Big Black River on May 12; it reopened June 1. Another portion of U.S. Highway 61 near Redwood was closed by backwater flooding along the Yazoo River on May 13 and was closed until June 3.[25]

In anticipation of major flooding, the U.S. federal government declared 14 counties along the Mississippi River, the Thames River: Adams, Bolivar, Claiborne, Coahoma, DeSoto, Humphreys, Issaquena, Jefferson, Sharkey, Tunica, Warren, Washington, Wilkinson and Yazoo.[26]

The Flood of 2011 set new record stages at Vicksburg and Natchez.[27][28] The peak streamflow at Vicksburg, 2,310,000 cubic feet per second (65,000 m3/s), exceeded both the estimated peak streamflow of the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927, 2,278,000 cu ft/s (64,500 m3/s), and the measured peak streamflow of the 1937 flood, 2,080,000 cu ft/s (59,000 m3/s).[29][30] The Project Design Flood predicts that a flowrate at Vicksburg of 2,710,000 cubic feet per second (77,000 m3/s) would still be within the limits of the downstream capacities, meaning that the May 17 - May 18 peak flow was about 85% of the acceptable flowrate for Vicksburg.

| Gage | Flood Stage (ft) | Crest Stage (ft) | Crest Date | Prior Record Stage (ft) | Prior Record Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Memphis | 34 | 47.8 | 10 May 2011 | 48.7 | 10 Feb 1937 |

| Helena | 44 | 56.5 | 12 May 2011 | 60.2 | 12 Feb 1937 |

| Arkansas City | 37 | 53.1 | 16 May 2011 | 59.2 | 21 Apr 1927 |

| Greenville | 48 | 64.2 | 16 May 2011 | 65.4 | 21 Apr 1927 |

| Vicksburg | 43 | 57.1 | 19 May 2011 | 56.2 | 4 May 1927 |

| Natchez | 48 | 61.9 | 19 May 2011 | 58.0 | 21 February 1937 |

Louisiana

This section's factual accuracy may be compromised due to out-of-date information. (February 2012) |

Following the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927, much effort has been invested in building defenses to withstand a flood of three million cubic feet per second just upstream from the Old River Control Structure. The US Army Corps of Engineers refers to this design goal as Project Flood.[32] the expected flow will be on the high side, but still within that maximum capacity, assuming everything works as expected.[33]

Morganza Spillway and Atchafalaya Basin

On May 14, a single floodgate of the Morganza Spillway was opened in order to divert 125,000 cubic feet per second (3,500 m3/s) of water from the Mississippi River to the Atchafalaya Basin. This diversion was deemed necessary to protect levees and prevent major flooding in Baton Rouge and New Orleans, with the tradeoff of exacerbating flooding in the Atchafalaya Basin, and will also reduce floodwater stress on the Old River Control Structure upstream. This was the first opening of the spillway since the 1973 flood.[7][34][35][36]

By May 15, a total of nine gates had been opened by the Corps of Engineers. The Corps had estimated that it would take opening one-fourth of the spillway's 125 bays—or 31 bays—to control the flow of the river through Baton Rouge in response to a forecast crest of 45 feet (14 m) anticipated on May 17, which must remain below 1,500,000 cu ft/s (42,000 m3/s) of water per second through Baton Rouge to ensure the integrity of the levee system.[37]

Prior to the decision to open more gates on the spillway, the Corps studied four flooding scenarios, all of which assumed the Bonnet Carré Spillway near New Orleans would be concurrently operating at full capacity (100%).

- Scenario 1: Open the Morganza Spillway to half (50%) of its maximum capacity, which would divert 300,000 cubic feet per second (8,500 m3/s) of water.

- Scenario 1a: Open the Morganza Spillway to one-quarter (25%) of its maximum capacity, which would divert 150,000 cubic feet per second (4,200 m3/s) of water.

- Scenario 2: Do not open the Morganza Spillway, and keep the Old River Control Structure at its routine operating level of only 30% of the Mississippi's flow; no additional water would be diverted

- Scenario 3: Do not open the Morganza Spillway, and open the Old River Control Structure somewhat more, which would divert an extra 150,000 cubic feet per second (4,200 m3/s) of water.

Following this analysis, which showed that extensive flooding was expected in the Atchafalaya Basin regardless of the choice made regarding the Morganza Spillway, the Corps decided to start the 2011 diversion by opening the spillway a bit less than described in scenario 1a (21%, not 25%)[34]

The Corps of Engineers subsequently released a map showing the estimated times it would take the flood waters to reach the various communities in the Atchafalaya Basin over eight days.[38]

- United States Army Corps of Engineers 2011 Louisiana Flooding Scenarios

-

Anticipated inundation from Scenario 1

-

Anticipated inundation from Scenario 1a

-

Anticipated inundation from Scenario 2

-

Anticipated inundation from Scenario 3

- Source

- United States Army Corps of Engineers[39]

-

Atchafalaya Basin floodwater travel times from the Morganza Spillway.

-

Natural-colour satellite image of the Floodway on May 15, 2011.

-

False colour satellite image of the Floodway on May 15, 2011.

Waterford Nuclear Generating Station

The Waterford Nuclear Generating Station, about 25 miles (40 km) west of New Orleans, was restarted May 12,[40][41] after a refueling shutdown on April 6.[42]

Bonnet Carré Spillway and Lake Pontchartrain

The Bonnet Carré Spillway, near New Orleans, was built to divert water from the Mississippi River to Lake Pontchartrain, and from there to the Gulf of Mexico, reducing water levels and flow near New Orleans. On May 23, 2011, 330 of the structure's 350 bays were opened due to rising water levels otherwise anticipated to jeopardize levees protecting New Orleans.[43] The Army Corps of Engineers began closing the spillway gates on June 12 as the river level began to fall and the last of the gates were closed on June 20.[44]

Climate factors

The Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) satellites indicated a continued water storage increase over the Missouri River Basin (MRB) prior to the 2011 flood event.[45] A 2014 study [46] examined what climate forcing conditions preceded the long-term changes in these variables. It was found that precipitation over the MRB undergoes a profound modulation during the transition points of the Pacific quasi-decadal oscillation and associated teleconnections. The results infer a prominent teleconnection forcing in driving the wet/dry spells in the MRB, and this connection implies persistence of dry conditions for the next 2 to 3 years.

Risk of major course change in the Lower Mississippi River

During the 2011 floods, concerns were raised that the Mississippi might divert its main channel into the Atchafalaya Basin if the Old River Control Structure, the Morganza Spillway, or nearby levees failed, or into Lake Pontchartrain if the Bonnet Carré Spillway or adjacent levees failed.[47][48][49][50][51] Jeff Masters of the Weather Underground noted that failure of the Old River Control Structure "would be a serious blow to the U.S. economy, and the great Mississippi flood of 2011 will give [this structure] its most severe test ever."[52]

During the 2011 floods, the Army Corps of Engineers decided to open the Morganza Spillway at 1/4 of its capacity to allow 150,000 cu ft/s (4,200 m3/s) to enter the Morganza and Atchafalaya floodways.[14] In addition to reducing the 2011 flood crest downstream, this reduced the chances of a channel change by reducing stress on the other elements of the control system.[33]

See also

- 2011 Missouri River Flood

- 2011 Assiniboine River Flood

- 2011 Red River Flood

- 2011 Souris River flood

- 2011 Super Outbreak

- Atchafalaya River

- Bird's Point, Missouri

- Great Mississippi and Missouri Rivers Flood of 1993

- Great Mississippi Flood of 1927

- Ohio River flood of 1937

- Old River Control Structure

References

- ^ a b "Tornado victims seek comfort in Sunday services". CBS News. May 1, 2011. Retrieved May 1, 2011.

- ^ a b "Heavy Rain/Severe Weather on April 23–27, 2011". National Weather Service in Little Rock, Arkansas. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. April 27, 2011. Retrieved April 28, 2011.

- ^ a b "Top federal officials tour, promise help to tornado-ravaged South". CNN. May 1, 2011. Retrieved May 1, 2011.

- ^ Masters, Jeffrey. "Mississippi River flood of 2011 already a $2 billion disaster". Weather Underground. Jeff Masters' WunderBlog. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- ^ Strauss, Gary; Marisol Bello (May 11, 2011). "Mississippi flood damages could reach billions". Tucson Citizen. Retrieved 12 May 2011.[dead link]

- ^ "Obama Signs Tennessee Disaster Declaration". Blog.memphisdailynews.com. 2011-05-09. Archived from the original on 15 June 2011. Retrieved 2011-05-16.

- ^ a b "Rural Louisiana flooded to save New Orleans" (CBS News/Associated Press) May 14, 2011

- ^ "River floods 100 homes; state's death toll at 14". Arkansasonline.com. 2011-04-30. Retrieved 2011-05-16.

- ^ "BBC News - Mississippi flood: Southern states brace for crest". Bbc.co.uk. 2011-05-11. Archived from the original on 13 May 2011. Retrieved 2011-05-16.

- ^ "Gov Jindal: Morganza Spillway opening by Saturday". Times Union. 2011-05-12. Archived from the original on 2012-09-13. Retrieved 2011-05-16.

- ^ "Flooding begins to 'wrap arms' around Memphis" May 7, 2011 (Toronto Sun)

- ^ Paul Rioux (May 16, 2011) "Many in way of diverted Mississippi River floodwaters ignore evacuation order" The Times-Picayune

- ^ "Memphis and Baton Rouge brace for record-breaking Mississippi flood". Christian Science Monitor. 2011-05-08. Archived from the original on 24 May 2011. Retrieved 2011-05-16.

- ^ a b Estimated Inundation (US Army Corps of Engineers) Archived May 11, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Mississippi River rise has River Parishes residents worried" NOLA.com May 12, 2011

- ^ "'Sacrificial' towns prepare for deliberate flooding" MSNBC May 12, 2011

- ^ "Officials try to calm fears of New Orleans flooding from Mississippi River" Archived May 15, 2011, at the Wayback Machine WWL TV May 12, 2011

- ^ This latter storm produced over 250 tornadoes, the deadliest tornado outbreak since 1936, causing an estimated $11 billion dollars in damage.

- ^ "Levee breach lowers river, but record flooding still forecast". CNN. May 3, 2011. Retrieved 2011-05-03.

- ^ "Court approves breaching of Birds Point levee". KSDK Cairo, Ill.

- ^ "Hundreds of Structures Underwater in Dyersburg". WREG Memphis.

- ^ "Man drowned in floodwaters in eastern Arkansas". Associated Press. May 5, 2011.

- ^ "Rising waters flood Tunica casinos". WMC. 2011-05-05. Archived from the original on 2011-05-09. Retrieved 2011-05-05.

- ^ http://vicksburgpost.com/view/full_story/13125472/article-Eagle-Lake-residents-told-to-evacuate-Highways--levees--rails-shutting-down-

- ^ http://vicksburgpost.com/view/full_story/13215521/article-61-closing-north-and-south-by-weekend-Flood-closes-second-casino-

- ^ "On the water?".

- ^ U.S. National Weather Service. "Crest Summary Map along the Lower Mississippi River and Backwater Locations". Retrieved 29 May 2011.

- ^ http://vicksburgpost.com/view/full_story/14361466/article--River-below-43-feet-Historic-flood-over-%E2%80%94-on-the-books-

- ^ WaterWatch. "WaterWatch: Water Resources Conditions, Peak, Discharge". USGS. Retrieved 1 June 2011.

- ^ Peak Streamflow. "USGS 07289000 MISSISSIPPI RIVER AT VICKSBURG, MS". USGS. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- ^ U.S National Weather Service. "Mississippi River Hydrographs". Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- ^ a b "The Mississippi River & Tributaries Project: Designing the Project Flood" (PDF). United States Army Corps of Engineers. April 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 23, 2011.

- ^ a b Contributing Op-Ed columnist. "Floods are a reminder of the Mississippi River's power: John Barry". NOLA.com. Retrieved 2011-05-16.

- ^ a b Paul Rioux, The Times-Picayune. "Morganza Floodway opens to divert Mississippi River away from Baton Rouge, New Orleans". NOLA.com. Retrieved 2011-05-16.

- ^ "Morganza Floodway". US Army Corps of Engineers. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 2011-05-08.

- ^ The Watchers. "US 2011 Great Flood: Morganza spillway about to open". Thewatchers.adorraeli.com. Retrieved 2011-05-16.

- ^ KENNEDY, KATIE (15 May 2011). "Planning for high water". The Advocate. Archived from the original on May 18, 2011. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- ^ The Times-Picayune (May 16, 2011) "New maps of Mississippi River, Atchafalaya River estimated flooding released by Corps"

- ^ "The Mississippi River". United States Army Corps of Engineers. 2011-05-09. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 2011-05-12.

- ^ "NRC: Power Reactor Status Report for May 11, 2011". Nuclear Regulatory Commission. 2011-05-11. Retrieved 2011-05-16.

- ^ "NRC: Power Reactor Status Report for May 13, 2011". Nuclear Regulatory Commission. 2011-05-13. Retrieved 2011-05-16.

- ^ "NRC: Power Reactor Status Report for April 6, 2011". Nuclear Regulatory Commission. Retrieved 2011-05-16.

- ^ "U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Team New Orleans". Archived from the original on May 21, 2011. Retrieved May 13, 2012.

- ^ "Last gates at Bonnet Carre Spillway closed". Associated Press. June 20, 2011. Retrieved 2011-06-22.

- ^ "Video Gateway".

- ^ Wang et al. (2014) DOI: 10.1002/2013GL059042 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/2013GL059042/abstract

- ^ McPhee, John (1987-02-23). "McPhee, The Control of Nature: Atchafalaya". The New Yorker. Retrieved 2011-05-16.

- ^ "Will the Mississippi River change its course in 2011 to the red line?". Mappingsupport. Retrieved 2011-05-08.

- ^ "Morganza ready for flood | The Advertiser". theadvertiser.com. 2011-05-12. Retrieved 2011-05-16.[dead link]

- ^ Mark Schleifstein, The Times-Picayune. "Mississippi River flooding in New Orleans area could be massive if Morganza spillway stays closed". NOLA.com. Retrieved 2011-05-16.

- ^ "Bonnet Carre Spillway, Norco, LA". Johnweeks.com. 2008-04-10. Retrieved 2011-05-16.

- ^ "America's Achilles' heel: the Mississippi River's Old River Control Structure: Wunder Blog". Wunderground.com. Retrieved 2011-05-16.

External links

- Before and after satellite images

- NASA; The Weather Channel, May 4

- before and after images from IBTimes.com, May 12

- animated javascript version from HuffingtonPost.com, May 12

- Kentucky to Mississippi State from NASA, May 20

- Satellite images of flooding from NASA Earth Observatory

- Advanced Hydrologic Prediction Service - NOAA

- Mississippi river flood gauges (National Weather Service)

- US Army Corps of Engineers Mississippi River Flood Fight

- Photos: Mississippi River flooding at The Big Picture, Boston.com

- Interactive satellite and topographic maps from the Old River Control Structure to the Gulf

- General Weather Conditions and Precipitation Contributing to the 2011 Flooding in the Mississippi River and Red River of the North Basins, December 2010 through July 2011 United States Geological Survey

- Streamflow Characterization and Summary of Water-Quality Data Collection During the Mississippi River Flood, April through July 2011 United States Geological Survey

- 2011 floods

- 2011 natural disasters in the United States

- Mississippi River floods

- Natural disasters in Arkansas

- Natural disasters in Illinois

- Natural disasters in Kentucky

- Natural disasters in Mississippi

- Natural disasters in Missouri

- Natural disasters in Tennessee

- Floods in Louisiana

- 2011 in Arkansas

- 2011 in Illinois

- 2011 in Kentucky

- 2011 in Mississippi

- 2011 in Missouri

- 2011 in Louisiana

- 2011 in Tennessee

- May 2011 events in the United States

- June 2011 events in the United States