Old Kent Road

Looking south along Old Kent Road from the Bricklayers Arms | |

| Former name(s) | Watling Street |

| Part of | A2 |

| Maintained by | Transport for London |

| Length | 1.8 mi (2.9 km) |

| Location | Southwark, South East London |

| Postal code | SE1; SE15 |

| Nearest Transport for London station |

|

| Coordinates | 51°29′02″N 0°03′59″W / 51.48390°N 0.06635°W |

| Other | |

| Known for | |

Old Kent Road[a] is a major thoroughfare in South East London, England, passing through the London Borough of Southwark. It was originally part of an ancient trackway that was paved by the Romans and used by the Anglo-Saxons who named it Wæcelinga Stræt (Watling Street). It is now part of the A2, a major road from London to Dover. The road was important in Roman times linking London to the coast at Richborough and Dover via Canterbury. It was a route for pilgrims in the Middle Ages as portrayed in Chaucer's Canterbury Tales, when Old Kent Road was known as Kent Street. The route was used by soldiers returning from the Battle of Agincourt.

In the 16th century, St Thomas-a-Watering on Old Kent Road was a place where religious dissenters and those found guilty of treason were publicly hanged. The road was rural in nature and several coaching inns were built alongside it. In the 19th century it acquired the name Old Kent Road and several industrial premises were set up to close to the Surrey Canal and a major business, the Metropolitan Gas Works was developed. In the 20th century, older property was demolished for redevelopment and Burgess Park was created. The Old Kent Road Baths opened around 1905 had Turkish and Russian bath facilities. In the 21st century, several retail parks and premises typical of out-of-town development have been built beside it while public houses have been redeveloped for other purposes.

The road is celebrated in the music hall song "Knocked 'em in the Old Kent Road", describing working-class London life. It is the first property, and one of the two cheapest, on the London Monopoly board and the only one south of the River Thames.

Geography

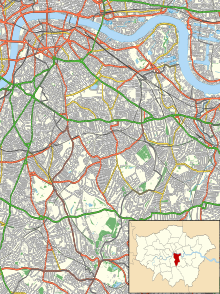

The road begins at the Bricklayers Arms roundabout, where it meets the New Kent Road, Tower Bridge Road, and Great Dover Street. It runs southeast past Burgess Park, Christ Church, Peckham and the railway line from Peckham Rye to South Bermondsey.[2]

Just east of the railway bridge, the road crosses the boundary between the London boroughs of Southwark and Lewisham, where the road ahead becomes New Cross Road. The road appears on a map to form a boundary between Walworth, and Peckham to the south and Bermondsey to the north although the Bermondsey boundary runs along Rolls Road.[2]

History

Old Kent Road, one of the oldest roads in England, was part of a Celtic ancient trackway that was paved by the Romans and recorded as Inter III on the Antonine Itinerary.[3][4] The Anglo-Saxons named it "Wæcelinga Stræt" (Watling Street). It joined Stane Street, another ancient and Roman road, at Southwark before crossing the Thames at London Bridge.[4] The Inter III was one of the most important Roman roads in Britain, linking London with Canterbury and the Channel ports at Richborough (Rutupiae); Dover (Dubris) and Lympne (Lemanis).[3] Pilgrims, as documented in Chaucer's Canterbury Tales, travelled along the road from London and Southwark on their way to Canterbury.[1][b] In 1415, the road was a scene of celebrations for soldiers returning from the Battle of Agincourt heading towards London.[6] The Kentish Drovers public house opened in 1840 and was so named because the road was a thoroughfare for market traffic.[7] The road was mainly rural in nature, surrounded by fields and windmills and the occasional tavern until the 19th century.[6] John Rocque's Map of London, published in 1746, shows hedgerows along its course.[1] The name Old Kent Road came into use at this time; up to then the road from Borough High Street to the Bricklayers Arms junction was known as Kent Street, this section was renamed Tabard Street in the 1890s.[8]

St Thomas-a-Watering

The bridge at St Thomas-a-Watering over the River Neckinger was at the junction with what is now Old Kent Road and Shorncliffe Road (previously Thomas Street),[9] and marked the boundary of the Archbishop of Canterbury's authority over the manors of Southwark and Walworth.[1] It was the limit of the City of London's authority in 1550, having been ratified in several charters and marked by a boundary stone set into the wall of the old fire station[10] that marked the first resting place for pilgrims while travelling to Canterbury. A nearby public house, the Thomas a Becket, at the corner of Albany Road was named after this.[1] Henry V met soldiers returning from Agincourt at this location in 1415.[11] Charles II's journey along the road on his way to reclaim the throne in May 1660 was described by contemporary writer and diarist John Evelyn as "a triumph of about 20,000 horse and foote, brandishing their swords and shouting with inexpressible joy".[1]

St Thomas-a-Watering became a place of execution for criminals whose bodies were left hanging from the gibbets on the principal route from the southeast to London. On 8 July 1539, Griffith Clerke, Vicar of Wandsworth was hanged and quartered here along with his chaplain and two others, for not acknowledging the royal supremacy of Henry VIII.[12] The Welsh Protestant martyr John Penry was also executed here on 6 April 1593;[13] a small side street nearby is named after him. The Catholic martyrs John Jones and John Rigby were executed in 1598 and 1600 respectively.[14][15]

Rolls family

In the early-18th century, the Rolls family of The Grange in nearby Bermondsey acquired a significant amount of land around Old Kent Road.[8] It included residential development that is now Surrey Square and the Paragon, which were designed by Michael Searles in 1788.[16] The main road route gave rise to ribbon development because of the increasing urbanisation of the expanding metropolitan area. In the early-20th century, social housing was built on land previously held by the family who gave away their interests for public benefit including the library at Wells Way in Burgess Park, the girls grammar school at Bricklayers Arms (St Saviour's and St Olave's School) and the Peabody Estate (Dover Flats and Waleran Flats).[17] The last significant remnant of their involvement is the detached White House between the Peabody Estate buildings, built by Searles in the 1790s. The original railings and ironwork survive in the current development at No. 155.[17] The house was later occupied by Searles and became the management office of the Rolls family trust estates.[8] The last of the male Rolls's was the Hon Charles Stewart Rolls who was the pioneer motorist and aviator who formed the Rolls-Royce partnership with Henry Royce.[18]

Industrial development

The opening of the Surrey Canal in 1811[19] changed the character of the road from rural to industrial. Tanneries were established along it and a soap processing plant was built.[20][21] Older properties occupied by the upper and middle classes were converted into flats for the emerging working class population. By the time Bricklayers Arms goods station opened in 1845, the road was entirely built up and Old Kent Road had one of the highest population densities in Europe, with an average of 280 residents per acre.[20] Sections along the road were commercial with various market stalls and sellers until the construction of the tramway in 1871.[17][22] Camberwell Public Library No. 1, which later became the Livesey Museum for Children was designed by Sir George Livesey in 1890.[23] The road's southern section remained residential throughout the 19th century. Nos. 864, 866 and 880–884 were constructed by John Lamb in 1815, and feature Ammonite capitals, ornamental features resembling fossils, a feature also used in contemporary architecture in Brighton.[24]

The Licensed Victuallers' National Asylum (now Caroline Gardens), an extensive almshouse estate off Old Kent Road at Asylum Road, opened in 1827. Its first patron was Prince Augustus Frederick, Duke of Sussex who was followed by Prince Albert and Prince Edward.[1]

The Metropolitan Gas Works, identifiable by its large gasometers, was founded in 1833. It serviced an area of more than 13 square miles (34 km2), including parts of Southwark, Croydon, Newington, Lambeth and Streatham. Expansion of the gas works in 1868 required the demolition of Christ Church, Camberwell which was built in 1838 and rebuilt on the opposite side of the road by Livesey.[1] The gas works was managed by Livesey from 1840 until his death in 1908. A statue of him was sited in the rear courtyard of Livesey Museum, opposite the works.[25]

During the 19th and 20th century, the industrial and working class makeup of Old Kent Road made it a haven for organised crime and violence. The notorious Richardson Gang operated in the area, and boxing clubs became popular. Lennox Lewis' manager Frank Maloney grew up in the area and recalled, "If you weren't into crime, people thought you were a pansy". Henry Cooper trained in the boxing club above the Thomas a Becket pub from 1954 to 1968; he unveiled a local blue plaque there in 2007. Draining the Surrey Canal in 1971 uncovered a number of cracked and blown safes that had been thrown in the water.[26]

Public services

Old Kent Road railway station at the southern end of the road opened in 1866 and closed in 1917.[24] The London City Fire Brigade opened a fire station on the road around 1868.[27] It was subsumed into the London Fire Brigade from its formation and in 1904 was replaced by a new station[28] which was in turn replaced by another on the corner of Coopers Road. The station was demolished for redevelopment in 2014 and reopened the following year.[29]

The Old Kent Road Baths were built in 1906.[30] According to Modern Sanitation, they were the only public baths in London with Turkish bath facilities at the time.[31] The baths were designed to include two swimming pools, each measuring 75 feet (23 m) by 30 feet (9.1 m).[32] In 1913-4, the baths were used by 188,336 private bathers, 14,687 of which used its Russian, Turkish,[33] or special electric baths.[34] The 1923 Municipal Year Book noted the "great success" of Turkish and Russian baths.[35]

Urban Redevelopment

Unlike many places in London, the Old Kent Road area did not suffer significant bomb damage during World War II.[36] In 1968, a flyover opened at the northern end allowing access to New Kent Road which catered for the main flow of traffic.[37][38] During the 1970s, run-down Victorian properties on and around Old Kent Road were demolished to make way for new housing estates.[39] Burgess Park was created as part of the County of London Plan in 1943, which recommended new parkland in the area. Several tower blocks were built along the road, although some earlier 19th-century buildings, such as Nos. 360–386, survived.[40]

Public houses on Old Kent Road have been closing since the 1980s. At one point, there were 39 pubs. The Dun Cow at No. 279 opened in 1856 and was well known as a gin palace, and later became a champagne bar and featured DJs such as Steve Walsh and Robbie Vincent. The premises closed in 2004 to become a surgery.[41] The World Turned Upside Down had been on the Old Kent Road since the 17th century, and may have been named after the discovery of Australia, Van Diemen's Land, or Tierra del Fuego in South America.[1] The pub became a music venue in the 20th century and is where Long John Baldrey gave his first live performance in 1958.[42] It closed in 2009 and is now a branch of Domino's Pizza.[43] The Duke of Kent was converted into a mosque in 1999; in 2011 the mosque was planned to move to the former site of the Old Kent Road swimming baths.[44] The Livesey Museum for Children closed in 2008 owing to council budget cuts and is now used for short term accommodation.[45]

Southwark Borough Council do not consider Old Kent Road to fit the characteristics of an urban town centre, and consequently large retail parks more in character with out-of-town schemes have been developed including a large Asda superstore, B&Q store, Halfords, Magnet and PC World.[46] Southwark Council have begun consultations on plans to redevelop much of the area, known as the Old Kent Road Area Action Plan.[47] This master plan would mimic similar regeneration projects in other London neighbourhoods such as Elephant & Castle,[48] Nine Elms and Canada Water. The consultations centre on a vision to open 4 new Bakerloo line London Underground stations along the road route, beginning at Bricklayers Arms, as well as 20,000 new homes, a further education college, a health centre and a number of primary and secondary schools.[49] Officials have also suggested the development of a "green spine" of parks and green spaces along the mostly disused Surrey Canal.[50]

Cultural references

| Income Tax Pay £200 |

Whitechapel Road £60 |

Community Chest | Old Kent Road £60 |

Collect £200 Salary As You Pass GO |

Old Kent Road is the first property square on the British Monopoly board, priced at £60 and forming the brown set along with the similarly working-class Whitechapel Road. It is the only square on the board in South London and south of the Thames.[23][51]

The road makes several appearances in literature. In Charles Dickens' David Copperfield, the titular character runs down the road trying to escape from London to Dover, though in the narrative the street is still partly rural in nature.[6] In 1985, the BBC arts series Arena included a documentary about the road.[52]

The road is mentioned in the title of the music hall song "Knocked 'em in the Old Kent Road". It was written in 1891 by Albert Chevalier, who was the lyricist and original performer; the music was written by his brother Charles Ingle.[53] The song was popularised by Shirley Temple's performance in the 1939 film A Little Princess[54] The street is mentioned multiple times in the Madness song "Calling Cards", a song about running an illegitimate business "in a sorting office in the Old Kent Road".[55] It is featured in the chorus of the Levellers' song "Cardboard Box City", which criticises the slow action on helping the homeless in London, specifically Old Kent Road being infrequently visited by the wealthy due to its being south of the Thames.[56] British girl group Girls Aloud refer to running down the road in the lyrics to their 2005 single "Long Hot Summer".[57]

References

Notes

Citations

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Walford, Edward (1878). "The Old Kent Road". Old and New London. Vol. 6. London. pp. 248–255. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b "London South" (Map). 1:25 000 Explorer. Ordnance Survey. 2015. 161.

- ^ a b Thomas Reynolds (1799). Iter Britanniarum. J. Burges. pp. 66–67.

- ^ a b M.C. Bishop (28 February 2014). The Secret History of the Roman Roads of Britain. Pen and Sword. p. 41. ISBN 9781473837256.

- ^ English Heritage 2009, p. 9.

- ^ a b c Moore 2003, p. 309.

- ^ English Heritage 2009, p. 108.

- ^ a b c Darlington, Ida, ed. (1955). "Tabard Street and the Old Kent Road". Survey of London. 25, St George's Fields (The Parishes of St. George the Martyr Southwark and St. Mary Newington). London: 121–126. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- ^ A. D. Mills (11 March 2010). A Dictionary of London Place-Names. Oxford University Press. p. 173. ISBN 978-0-19-956678-5.

- ^ Johnson, David (1969). Southwark and the City. Oxford University Press. p. 118.

- ^ Wheatley, Henry (1904). The Story of London. M. Dent & Co.

- ^ Walford, Edward (1878). "Wandsworth". Old and New London. 6: 479–489. Retrieved 27 July 2015.

- ^ "Pilgrim Fathers". London Borough of Southwark. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- ^ Butler, Alban; Burns, Paul (1995). Butler's Lives of the Saints. Vol. 7. A&C Black. p. 89. ISBN 978-0-860-12256-2.

- ^ Butler, Alban (1981). Butler's Lives of the saints. Vol. 3. Christian Classics. p. 87.

- ^ Cherry & Pevsner 1983, p. 596.

- ^ a b c English Heritage 2009, p. 8.

- ^ Moore 2003, p. 310.

- ^ A New British Atlas: Comprising a Series of 54 Maps, Constructed from the Most Recent Surveys and Engraved by Sidney Hall. Chapman V. Hall. 1836. p. 208.

- ^ a b Moore 2003, p. 311.

- ^ The Volta Review. Volta Bureau. 1927. p. 36.

- ^ "The Railway News". 17. London. June 1872: 511–512. Retrieved 11 September 2015.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b Weinreb et al 2008, p. 600.

- ^ a b English Heritage 2009, p. 107.

- ^ Mills, Mary (January 2004). "The Gas Workers Strike in South London". Greenwich Industrial History. 7 (1). Goldsmith's College, London. Archived from the original on 12 May 2004. Retrieved 10 August 2015.

- ^ Moore 2003, p. 317.

- ^ Nadal 2006, p. 67.

- ^ Nadal 2006, p. 104.

- ^ "Old Kent Road's new fire station opens as rebuild work begins at Dockhead fire station". London Fire Brigade News. 25 March 2015. Retrieved 10 August 2015.

- ^ Cross 1906, p. 220.

- ^ Modern Sanitation. Standard Sanitary Mfg. Company. 1909. p. 210.

- ^ The Surveyor and Municipal and County Engineer. 1904. p. 850.

- ^ "VICTORIAN TURKISH BATHS: Camberwell Turkish Baths: the cooling-room, 1905". Victorianturkishbath.org. 17 April 2001. Retrieved 26 September 2015.

- ^ Skoski 2000, p. 165.

- ^ The Municipal Year Book of the United Kingdom. Municipal Journal. 1923. p. 214.

- ^ Moore 2003, p. 323.

- ^ Moore 2003, p. 324.

- ^ "New Kent Road/Old Kent Road, London: flyover at Bricklayers Arms intersection". The National Archives. 1968. MT 118/409. Retrieved 27 August 2015.

- ^ Platt 2015, p. 43.

- ^ English Heritage 2009, p. 48.

- ^ Lock & Baxter 2014, p. 157.

- ^ Frame 1999, p. 94.

- ^ Lock & Baxter 2014, p. 156.

- ^ "New mosque planned for derelict Old Kent Road site". London SE1. 22 March 2011. Retrieved 27 August 2015.

- ^ Livesey Building FAQs (Report). London Borough of Southwark Council. pp. 1–2. Retrieved 11 September 2015.

- ^ Retail Background Paper (Report). Southwark London Borough Council. March 2010. p. 39. CDB5. Retrieved 27 August 2015.

- ^ "Home". Old Kent Road. Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- ^ "Elephant & Castle Partnership". Elephant and Castle. Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- ^ "Would you like a new town in Old Kent Road?". South London News. Retrieved 5 February 2018.

- ^ https://www.homesandproperty.co.uk/property-news/buying/new-homes/where-to-buy-a-home-near-southeast-londons-bakerloo-line-extension-a116716.html, Get the inside track: where to buy a home near south-east London's Bakerloo extension – Evening Standard

- ^ Moore 2003, p. 291.

- ^ "Old Kent Road (Arena)". London Screen Archives. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

- ^ Bratton 1986, p. 19.

- ^ Constable 2007, p. 110.

- ^ "Calling Cards". Madness (official website). Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- ^ "Cardboard Box City". Levellers Tabs. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- ^ Girls Aloud – Long Hot Summer, retrieved 30 June 2020

Sources

- Bratton, Jacqueline S. (January 1986). Music Hall: Performance and Style. Open University Press. ISBN 978-0-335-15131-8.

- Cherry, Bridget; Pevsner, Nikolaus (1983). London 2: South. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-09651-4.

- Constable, John (28 May 2007). Secret Bankside: Walks in the Outlaw Borough. Oberon Books. ISBN 978-1-84943-869-8.

- Cross, Alfred William Stephens (1906). Public Baths and Wash-houses: A Treatise on Their Planning, Design, Arrangement, and Fitting, Having Special Regard to the Acts Arranging for Their Provision, with Chapters on Turkish, Russian, and Other Special Baths, Public Laundries, Engineering, Heating, Water Supply, Etc. B. T. Batsford.

- Frame, Pete (1999). Pete Frame's Rockin' Around Britain: Rock'n'roll Landmarks of the UK and Ireland. Music Sales Group. ISBN 978-0-711-96973-5.

- Lock, Darren; Baxter, Mark (2014). Walworth Through Time. Amberley Publishing Limited. ISBN 978-1-445-63198-1.

- Moore, Tim (2003). Do Not Pass Go. Vintage. ISBN 978-0-099-43386-6.

- Nadal, John (2006). London's Fire Stations. Jeremy Mills Publishing. ISBN 978-0-954-64847-3.

- Platt, Geoff (2015). The London Underground Serial Killer. Wharncliffe. ISBN 978-1-473-85830-5.

- Skoski, Joseph R. (2000). Public Baths and Washhouses in Victorian Britain, 1842–1914. Indiana University.

- Weinreb, Ben; Hibbert, Christopher; Keay, Julia; Keay, John (2008). The London Encyclopedia. Pan MacMillan. ISBN 978-1-4050-4924-5.

- Old Kent Road Survey (Report). English Heritage / Southwark Borough Council. 2009. Retrieved 6 August 2015.