Udarnik

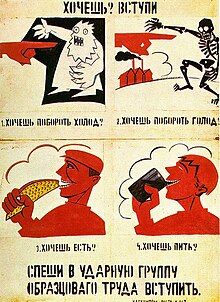

In the terminology of the Soviet Union, the Eastern Bloc, and other communist countries, an udarnik (/uːˈdɑːrnɪk/,[1] plural udarniks or udarniki; Russian: уда́рник, IPA: [ʊˈdarnʲɪk]), also known in English as a shock worker[2] or strike worker (collectively known as shock brigades[3] or a shock labor team[4]) is a high productivity worker. It derived from the expression "udarny trud" for "superproductive, enthusiastic labor".[5]

Soviet Union

[edit]In the Soviet Union, the term was linked to Shock worker of Communist Labour (Ударник коммунистического труда), a Soviet honorary title, as well as Alexey Stakhanov and the movement named after him. However, the terminology of shock workers has also been used in other socialist states, most notably in the People's Republic of China,[6] North Korea,[7] the People's Republic of Bulgaria,[8][9] and the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia.[10][11]

Soviet shock workers were not always necessarily citizens of the USSR, as one British communist and trade union leader Jessie Eden, was elected one at the Stalin automotive plant (later renamed the ZiL automotives).[12]

The hope behind promoting shock labour was that through socialist emulation the rest of the workforce would learn from the vanguard.[13][14]

The Soviet Union promoted shock work during the First Five-Year Plan period in an effort to increase productivity through human effort in the absence of more developed machinery.[15]: 57

Cultural theorist Susan Buck-Morss contrasts shock work's stimulation of productivity in rushes of labor with the standardization of Taylorism.[15]: 57

In Poland

[edit]In People's Republic of Poland a similar title was przodownik pracy (translated into English as "model worker"),[16] a calque from another Soviet/Russian term peredovik proizvodstva, literally "leader in production". Seen as the Polish version of the Stakhanovite movement,[17] famous Polish workers given the title of przodownik pracy included Piotr Ożański[16] and especially the "Polish Stakhanov" Wincenty Pstrowski, a miner who in 1947 achieved 270 percent expected efficiency per month.[18] Later Pstrowski died due to misconducted dental intervention, but in official propaganda, it was due to deadly exhaustion.[19]

In Czechoslovakia

[edit]In the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic, an udarnik was called úderník[20] (with slightly different pronunciation in the Czech and Slovak languages). Úderníci were elite workers who surpassed their work quotas and were used by the Party as propaganda. This breaking of production quotas, while usually real and often reaching astounding heights of the order of several hundred percent, was achieved at the cost of substandard quality, lack of work safety regulations and lack of concern for personal health. Most importantly, úderníci usually did not perform any minor tasks mandated by the job standards they were supposed to follow. These tasks were performed by other workers, yet this work counted towards the úderník's quota.[citation needed]

References

[edit]- ^ "udarnik". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/OED/3650501751. Retrieved 2024-08-14. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ Moskvin, V.D., 1970. Development of socialistic competition and the introduction of the Saratov system of defectless [sic] production at the Volga-Don chemical combine. Chemistry and Technology of Fuels and Oils, 6(3), pp.190-192.

- ^ Lewis H. Siegelbaum (29 June 1990). Stakhanovism and the Politics of Productivity in the USSR, 1935-1941. Cambridge University Press. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-521-39556-4.

- ^ Asia and Africa Today. Asia and Africa Today. 1991. p. 464.

- ^ Art and Its Global Histories: A Reader. Oxford University Press. 16 June 2017. p. 309. ISBN 978-1-5261-1992-6.

- ^ An Chen (1999). Restructuring Political Power in China: Alliances and Opposition, 1978-1998. Lynne Rienner Publishers. p. 94. ISBN 978-1-55587-842-9.

- ^ Charles K. Armstrong (15 April 2013). The North Korean Revolution, 1945–1950. Cornell University Press. p. 162. ISBN 978-0-8014-6880-3.

- ^ Martin Mevius (13 September 2013). The Communist Quest for National Legitimacy in Europe, 1918-1989. Routledge. p. 64. ISBN 978-1-317-98640-9.

- ^ Yannis Sygkelos (19 January 2011). Nationalism from the Left: The Bulgarian Communist Party During the Second World War and the Early Post-War Years. BRILL. p. 227. ISBN 978-90-04-19208-9.

- ^ Daniel J. Goulding (2002). Liberated Cinema: The Yugoslav Experience, 1945-2001. Indiana University Press. p. 106. ISBN 0-253-34210-4.

- ^ Jelena Batinić (12 May 2015). Women and Yugoslav Partisans: A History of World War II Resistance. Cambridge University Press. p. 219. ISBN 978-1-107-09107-8.

- ^ Stevenson, Graham. "Eden Jessie: The Real Jessie Eden and Peaky Blinders". Encyclopedia of Communist Biographies. Retrieved 18 February 2021.

- ^ The Soviet Economy. Ardent Media. 1968. p. 268. GGKEY:1SK4L7X01QE.

- ^ Stephen E. Hanson (9 November 2000). Time and Revolution: Marxism and the Design of Soviet Institutions. Univ of North Carolina Press. p. 163. ISBN 978-0-8078-6190-5.

- ^ a b Li, Jie (2023). Cinematic Guerillas: Propaganda, Projectionists, and Audiences in Socialist China. New York, NY: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231206273.

- ^ a b Lebow, K. A. (2001) "Public Works, Private Lives: Youth Brigades in Nowa Huta in the 1950s," Contemporary European History. Cambridge University Press, 10(2), pp. 199–219. doi: 10.1017/S0960777301002028.

- ^ International Free Trade Union News. Free Trade Union Committee of the American Federation of Labor. 1949.

- ^ Ben Fowkes (27 July 2016). Rise and Fall of Communism in Eastern Europe. Springer. p. 13. ISBN 978-1-349-24218-4.

- ^ The Polish Review and East European Affairs. Polish Review, Incorporated. 1949. p. 72.

- ^ Kimberly Elman Zarecor (2011). Manufacturing a Socialist Modernity: Housing in Czechoslovakia, 1945-1960. University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-8229-7780-3.