African vulture trade

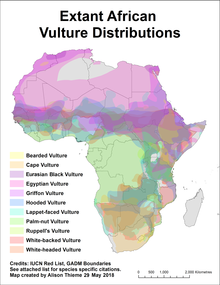

The African vulture trade involves the poaching, trafficking, and illegal sale of vultures and vulture parts for bushmeat and for ritual and religious use, like traditional medicines, in Sub-Saharan Africa. This illegal trade of vultures and vulture parts is contributing to a population crisis on the continent. In 2017, the IUCN Red List categorized 7 of Africa's 11 vulture species as globally endangered or critically endangered.[1] Recent research suggests that 90% of vulture species declines in Africa may be due to a combination of poisoning and illegal wildlife trade for medicinal use and/or bushmeat.[2] All trade of African vultures is illegal, as these birds are protected by international laws.[3]

African vulture trade falls under the broader spectrum of wildlife trade, with both national and international trade occurring. Vultures are sometimes specifically targeted for bushmeat consumption or traditional belief use. Poachers also target vultures, even when they are not harvesting the vultures for bushmeat or belief use purposes.[4] Since vultures circle over carcasses, they can be used as sentinels, alerting wildlife authorities of poaching events.[4] Ivory poachers and rhino horn poachers have thus targeted vultures to reduce the likelihood of being caught.[4]

Bushmeat

[edit]

Bushmeat is meat harvested from non-domesticated animals including mammals, amphibians, reptiles, and birds. Poachers target vulture species in sub-Saharan Africa for bushmeat harvest and consumption.[2][5] Poaching and harvest of vultures for market trade usually involves poisoning the birds by baiting livestock and wildlife carcasses with agrochemicals. This attracts the vultures to feed, as they are obligate scavengers. The birds eat the poisoned meat and die, making the harvest easy. However, the poisons the vultures ingest are passed along through the food chain which places the humans that consume these birds also at risk for poisoning. The two leading causes for vulture deaths are poisoning and trade in traditional medicine, these two causes make up 90% of reported deaths.[2]

Southern Africa

[edit]There is a scarcity in the literature regarding the use of vultures as bushmeat in Southern Africa. Mentions of bushmeat consumption in Southern Africa do exist in the literature, as families in the region are reported as saying in a study on the use of natural resources, that they consume bushmeat a few times a year.[6] However the specific use of vultures for bushmeat is not often discussed. The existing literature points to the existence of wildlife ranches in South Africa that contribute to the local economy,[7] privately owned game ranches and Transfrontier Conservation Areas as a possible contributors to this gap.[8]

The literature also indicates that the region of Southern Africa is a hub for illegal wildlife trafficking and the illegal wildlife market.[9] Birds are mentioned as one of the groups of animals most significantly impacted by the illegal wildlife trade.[9] This indicates that while there is no specific mention of consumption of vultures as bushmeat, birds are still being moved throughout the region and consumption or use elsewhere is still a driver for the activity.[9]

East Africa

[edit]

While other regions of Africa have higher incidence of poisoning for bushmeat consumption, the practice also exists in East Africa.[10] Specific countries, such as Kenya have experienced high rates of bird deaths from poisoning related to bush meat trade, with over 3,000 deaths reported in a 10-month period.[10] Countries in East Africa, such as Tanzania, have seen increased bushmeat consumption due to a need for protein and income.[11] However, there is no specific data regarding the sale of vultures in Tanzania's markets.

The limited reporting of vultures used as bushmeat may indicate the minimal numbers of vultures sold for food or represent a lack of published research on this topic in East Africa. This is similar to the lack of documentation available in Southern Africa.

West Africa

[edit]

West Africa consists of the following 15 countries: Benin, Burkina Faso, Cabo Verde, Gambia, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ghana, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Togo. Of these western countries, some have fairly stable vulture populations such as the Hooded Vultures of The Gambia and Guinea-Bissau.[12] On the other hand, there are countries like Senegal which has regions that have faced 80% vulture decline in the last half century.[13] The trade of vultures for bushmeat, as well as belief use, is the primary factor for the decline of vulture population in West Africa.[14]

Like many other animals, vultures found in West Africa are threatened by human-wildlife conflict. A study done throughout the continent found that although vulture losses could be seen everywhere, the highest total loss per year were in West and East Africa.[2] The killing of many species is an integral part of human livelihood in the region.[15] Human pressures on bushmeat populations are growing more rapidly than national population statistics suggest.[16] Over time the hunting of bushmeat has morphed from traditional subsistence to commercial trade. An increasing population and spread of urbanization has been thought to be one of the leading causes of increases in commercial bushmeat sales.[15] Hunting bushmeat in West Africa is also an important part of the livelihood for many people who live there. It is also a big part of the culture in Central and West Africa because bushmeat is their most important source of protein. Important as this is for the humans who rely on the bushmeat, it puts the survival of many species of vultures found in West Africa at risk.

There are many impacts associated with the vulture bushmeat market. Some purchasers believe that vulture parts would help them be cured from any diseases or illness they are enduring.[14] Impacts on the environment are also a result of bushmeat acquisition in West Africa. Specifically habitat disturbance, level of protection, hunting pressure, and distance to market have reduced forests throughout the region.[17] The consumption of bushmeat has also affected the wildlife population, but has also raised deadly diseases known as the Ebola virus.[18] Human life is another risk due to bushmeat being eaten when it is known to be a non dietary supplement of solid food. There is a link between education and income status that evaluates why consumers in Africa are choosing bushmeat specifically.[18] There is no large scale regional effort to address the bushmeat problem in West Africa currently.

In Liberia, when conducting the experiment to test out the theory of socio-economic factors for bushmeat consumption, it was found that monthly income, years of education, and literacy were all factors that led to the purchases.[18] Due to the lack of knowledge and monetary funds, poor income families were forced to obtain the wild animal meat in order to feast and gain protein.

Central Africa

[edit]Vultures in Central Africa are being used as bushmeat and the market for vulture meat is growing.[5] Due to the great vulnerability of vultures increasing “prosecutions and hunting pressures” in Central Africa has led to a heavy decline of the vulture populations and increase of vulture bushmeat in Central African markets.[5] Although vultures are used for a variety of reasons in Central Africa, most are used as bushmeat and sold at bushmeat markets. Most bushmeat markets sell large bodied vultures which are mainly killed by poison. In a study done in areas of Nigeria and Cameroon, it is estimated that more than 900,000 reptiles, birds, and mammals are sold each year which is approximately 12,000 tonnes of terrestrial vertebrates. 8.42 tonnes of that was bird bushmeat, and vultures made up most of that.[19] Most of the vultures found in the study were being sold in rural areas of Cameroon.[19] Hooded and large bodied vultures are some of the most sold raptors. Combined with Black kite they make up 41% of the raptor bushmeat market in West and Central Africa.[5] In the bushmeat market, the most frequently traded species are those with scavenging behavior, generalist or savannah habitat use, and an afrotropical breeding range.[5] Approximately half of the vultures sold at bushmeat markets are on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List for threatened and endangered species.[5]

Belief use

[edit]Poachers also harvest vultures in sub-Saharan Africa to sell their parts to people for belief use practices, such as traditional medicine, African vudon, and witchcraft. As with bushmeat harvests, African vultures sold for belief use are usually hunted using poisoned baits. Therefore, when belief use practitioners consume the vulture or vulture parts as part of their activities, they also ingest the poisons used to kill the vulture.

Vultures in sub-Saharan Africa are known for their tremendous eyesight, and many believe their body parts can be used to see into the future. Some South African belief users inhale smoke from burned vulture brains to improve cognitive abilities or to improve their luck.[20]

Southern Africa

[edit]

South Africa

[edit]As it stands, a greater part of the literature addressing belief use in the southern region of Africa comes from South Africa. Many South Africans do not view traditional medicine as a secondary choice to Western medicine, but rather a better or parallel treatment for ailments that Western medicines do not adequately treat.[21]

The use of vultures for traditional medicine is a prominent feature of some South African cultures, such as the Zulu people.[21] In his study of muthi and its impacts on vultures, McKean explains some of the reasoning provided for vulture use. "Research confirms that vultures are used... for a range of purposes, but are believed to be most effective for providing clairvoyant powers, foresight, and increased intelligence".[21] Approximately 160 vultures are sold per year in eastern South Africa alone, contributing to an estimated 59,000 consumption events of various vulture parts.[21] The harvesting of vultures for the traditional medicine market on this scale significantly impacts vulture species population numbers. White-headed and Lappet-faced vultures could disappear entirely in approximately 27 years if drastic changes are not made to increase protective measures for these birds.[21]

Lesotho

[edit]Much like its neighboring country South Africa, in Lesotho, vultures are believed to have supernatural powers and to personify insight and power. In a study done by Beilis and Esterhuizen, parts used for belief use ranged from vulture eyes and hearts to feathers and bones. It was observed that wings and feathers were least popular while parts such as brains and eyes were more desirable to consumers. The parts sold by healers seemed to only be Cape Griffon vulture parts.[22]

Only 11% of the 318 registered traditional healers in the capital of Lesotho sold vulture parts in 1998. Healers that were interviewed testified to the fact that they only used one vulture a year, which would translate to 35 vultures being killed in a year. But this does not bring into account unregistered healers or the high demand that exists during elections or significant events of that nature. Beilis and Esterhuizen found that if each healer used one more vulture, it would have the potential to disrupt the breeding process of vultures the country.[22]

Zambia

[edit]Though there exists a lack of knowledge on the current status of vulture populations in Zambia, very few occurrences of vulture poisoning have been recorded. Zambia's vultures are predominantly sited in protected areas and game management areas and are believed to be healthy. The populations that don't inhabit these areas are the ones that might be seeing a decline in populations. The known cases of vulture deaths in Zambia generally happen right outside of national parks and in South Luangwa National Park these deaths were linked to belief use of vultures. Many of these dead vultures are said to have their heads removed for use in rituals.[23]

Zimbabwe

[edit]In Zimbabwe, the Southern Ground-Hornbill's population has dropped significantly outside of designated protection areas, and is now a national concern.[24] A study at a Zimbabwe market was conducted to evaluate the sale and use of the Southern Ground-Hornbill. 18% of the traders caught the Ground-Hornbills themselves, 18% acquired them opportunistically, and 64% are supplied by hunters. Seven main uses were expressed by market salesman: fighting or revenge, to eliminate bad spirits, protection, strength, achieving dreams or goals, preventing theft, and to bring ancestral spirits to young inyangas, also known as herbalists.[25]

East Africa

[edit]Little is known regarding vulture belief use in Eastern Africa.[26] It is unclear whether this dearth of information indicates limited use, or rather a lack of research conducted within the region.[27] Scholars have called for increased examination, particularly within the countries of Tanzania, Kenya, Uganda, and Ethiopia.[26][27]

The few studies that have been conducted suggest notable differences between East Africa and more prominent vulture-using regions such as Southern and West Africa.[27] These include differences in traditional, spiritual, and medicinal practices associated with Muti, West African Vodun, and East African witchcraft. Cultural taboos also differ between these regions.[27][28] For example, some groups within Kenya believe vultures to be unclean and ugly,[28] while others associate them with death and view them as bad omens.[29] Such perceptions may result in limited use and market demand for vulture species.[27]

West Africa

[edit]Belief use of vultures and other animals is a common occurrence in West Africa where practitioners of Vodun have been known to promote the consumption of vulture parts at their markets for decades.[30] Most vultures that are killed for traditional belief use are deliberately poisoned. Carcasses of other animals are laced with poison, which the vultures then feed on, so that many vultures and other raptors can be killed and harvested with a single poisoned carcass.[5] There are vast differences in the prevalence of vulture belief use between the various countries and populations in West Africa, due to cultural differences and different political regulations and policies. In some markets, the trade of animal parts for fetish practices have been completely banned, while in others there is a flourishing market and high demand for vultures.[31] Specifically, vulture consumption and belief use is associated with Vodun in West Africa. In this traditional belief system, all birds are believed to help against weaknesses in the body. Large vultures are believed to help against mental illnesses and disturbances, epileptic health concerns, and to cure bad eyesight. The Hooded Vulture is traditionally buried in the ground before the construction of a new house, because it is believed to bring good luck. At fetish markets, vultures are the most valuable birds, but their populations have severely decreased and so they are becoming very rare in most markets. However, in Nigeria, the numbers of vultures at fetish markets have doubled since early surveys were taken. The Palm-Nut vulture is highly valued, and their market price is competitive. The high pressure to hunt these increasingly rare birds is pushing their population towards extinction.[31]

In Ghana, several vultures, but mainly the larger Ruppell's Vulture, are seen as spiritual agents. In a study measuring the reactions of people towards the vultures, it was shown that due to traditions and cultural teachings, females and the elderly had stronger beliefs and values concerning vultures.[32] Due to British colonial rule, the use of animal parts in fetish traditional practices has declined greatly in Ghana, and vulture parts are, for the most part, unavailable. Some Yoruba women traders from Nigeria may bring bird parts to fetish markets, which were hunted in Nigeria and brought by these traders.[31]

A survey of vulture parts in markets throughout West Africa showed that the vulture trade is most prevalent in Nigeria.[31] Within the Southeast region of Nigeria, there is a group called; Ogoni People.[33] The Ogoni tolerate vultures due to them being a symbol of their ancestors. Due their respect for it, the Ogoni do not attempt to hurt or kill the bird. If one comes across a deceased vulture, they will bury it in similar fashion to the way they bury people. A 1992 study found Nigerian farmers use the Hooded vulture in traditional medicinal practices.[34] A survey of the fetish markets in Nigeria showed that the numbers of vultures had actually doubled overall, compared to earlier surveys. The trading of vultures in Nigeria is mostly handled by Yoruba women. There is an increasing pressure on hunters to obtain vultures, as their population decreases and their value rises.[31]

Central Africa

[edit]

Vultures are used for physical, mental diseases, bring good fortune, improve success in gambling and betting in business ventures. Sorcery and witchcraft are the top use, and this use stems from Nigeria. The most common way to kill the vultures for traditional medicine is poisoning them through a blowgun. It is the “silent, cheap, easy to obtain and use, and effective.” The common poison used is Lindane and it most commonly used in Cameroon.[35]

Wildlife-based medicinal products are sold commercially in an urban, traditional market. The trade in vultures in markets have contributed considerably to the decline of the vultures and other raptors. Approximately half of the vultures sold are on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List as a threatened or endangered species. [4] “In the past four years, approximately 1000 beheaded poisoned vultures have been found in Zambia, Zimbabwe, Cameroon, and Tanzania.

There was not a lot of readily available information about the beliefs and traditions in Central Africa, regarding vultures. The information found supported the idea that hooded vultures are the prominent vulture in the area. The use due to the demand being high, black kites head feathers are plucked as a substitute for the hooded vultures.[5] There are several instances in Central Africa were dealers are selling vulture heads for traditional medicine.[12] Vulture head was sold in Maroua, in Garoua 10-12 vultures heads were sold, another set of legs and a head sold in the market.

Other Causes for African Vulture Population Declines

[edit]Although vulture trade and consumption is a large threat to vultures, it is not the largest. A whopping 61% of vultures are killed by poisonings, intentional or unintentional. This is compounded by another 9% dying from being electrocuted by exposed wiring. In comparison, 29% were killed for use in traditional medicine, and 1% for food.[2] The main reason vulture poisonings are so prevalent is a by product of another broader problem endemic to Africa, poaching. Vultures are notorious scavengers and this hurts them doubly in this scenario. With a sharp increase in rhino and elephant poaching over the last few years poachers have been poisoning the carcasses to kill any circling vultures which might reveal their position to the local authorities. Additionally many pastoralists in Africa poison carcasses to kill marauding lions, hyenas, and wild dogs. These poisoning incidents can kill upwards of 40 vultures per carcass as well as a plethora of other nearby animals.

Vulture Conservation Programs and Organizations in Sub-Saharan Africa

[edit]- BirdLife International

- BirdLife South Africa

- Endangered Wildlife Trust

- Wildlife ACT

- Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife

- African Birds of Prey Sanctuary

- Raptor Rescue

- VulPro

- Eskom

References

[edit]- ^ CMS Raptors (2017) Multi-Species Action Plan to Conserve African-Eurasian Vultures (Vulture MsAP), Summary. UN Environment, Convention on Migratory Species Office - Abu Dhabi. http://www.cms.int/sites/default/files/document/cms_cop12_doc.24.1.4_annex3_vulture-msap_e.pdf

- ^ a b c d e Ogada, D., Shaw, P., Beyers, R. L., Buij, R., Murn, C., Thiollay, J. M., ... & Krüger, S. C. (2016). Another continental vulture crisis: Africa's vultures collapsing toward extinction. Conservation Letters, 9(2), 89-97.

- ^ "Convention on international trade in endangered species of wild fauna and flora" (PDF). CITES. Retrieved 18 October 2023.

- ^ a b c Ogada, Darcy; Botha, André; Shaw, Phil (October 2016). "Ivory poachers and poison: drivers of Africa's declining vulture populations". Oryx. 50 (4): 593–596. doi:10.1017/S0030605315001209. hdl:10023/8943. ISSN 0030-6053.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Buij, R., et al. “Trade of Threatened Vultures and Other Raptors for Fetish and Bushmeat in West and Central Africa.” Oryx, vol. 50, no. 04, 14 Aug. 2015, pp. 606–616. CambridgeCore, doi:10.1017/s0030605315000514.

- ^ Willcock, S., Hooftman, D., Sitas, N., O’Farrell, P., Hudson, M. D., Reyers, B., . . . Bullock, J. M. (2016). Do ecosystem service maps and models meet stakeholders’ needs? A preliminary survey across sub-Saharan Africa. Ecosystem Services,18, 110-117. doi:10.1016/j.ecoser.2016.02.038

- ^ Wilkie, D. S., Wieland, M., Boulet, H., Bel, S. L., Vliet, N. V., Cornelis, D., . . . Fa, J. E. (2016). Eating and conserving bushmeat in Africa. African Journal of Ecology,54(4), 402-414. doi:10.1111/aje.12392

- ^ John Hanks (2003) Transfrontier Conservation Areas (TFCAs) in Southern Africa, Journal of Sustainable Forestry, 17:1-2, 127-148, DOI: 10.1300/J091v17n01_08

- ^ a b c Warchol, G.L., Zupan, L.L., & Clack, W. (2003). Transnational Criminality: An Analysis of the Illegal Wildlife Market in Southern Africa. International Criminal Justice Review, 13(1), 1-27.

- ^ a b Ogada, D. L. (2014), The power of poison: pesticide poisoning of Africa's wildlife. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci., 1322: 1–20. doi:10.1111/nyas.12405

- ^ Nielsen, Martin Reinhardt. "Importance, cause and effect of bushmeat hunting in the Udzungwa Mountains, Tanzania: Implications for community based wildlife management." Biological conservation 128, no. 4 (2006): 509-516.

- ^ a b D L Ogada & R Buij (2011) Large declines of the Hooded Vulture Necrosyrtes monachus across its African range, Ostrich, 82:2, 101-113, DOI: 10.2989/00306525.2011.603464

- ^ Mullié, W. C., Couzi, F. X., Diop, M. S., Piot, B., Peters, T., Reynaud, P. A., & Thiollay, J. M. (2017). The decline of an urban Hooded Vulture Necrosyrtes monachus population in Dakar, Senegal, over 50 years. Ostrich, 88(2), 131-138.

- ^ a b Wageningen University. “Raptors in West and Central Africa threatened by trade for bushmeat and fetish.” Phys.org - News and Articles on Science and Technology, Oryx, 24 Aug. 2015, phys.org/news/2015-08-raptors-west-central-africa-threatened.html.

- ^ a b Bakarr, Mohamed, William Oduro, and Eureka Adomako. "WEST AFRICA: REGIONAL OVERVIEW OF THE BUSHMEAT CRISIS."

- ^ Barnes, R. F. (2002). The bushmeat boom and bust in West and Central Africa. Oryx, 36(3), 236-242.

- ^ McNamara, J.; Kusimi, J. M.; Rowcliffe, J. M.; Cowlishaw, G.; Brenyah, A.; Milner‐Gulland, E. J. (2015-10-01). "Long‐term spatio‐temporal changes in a West African bushmeat trade system". Conservation Biology (in Portuguese). 29 (5): 1446–1457. doi:10.1111/cobi.12545. ISSN 1523-1739. PMC 4745032. PMID 26104770.

- ^ a b c Ordaz-Ne´meth I, Arandjelovic M, Boesch L, Gatiso T, Grimes T, Kuehl HS, et al. (2017) The socio-economic drivers of bushmeat consumption during the West African Ebola crisis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 11(3): e0005450

- ^ a b Fa, John E.; Seymour, Sarah; Dupain, Jef; Amin, Rajan; Albrechtsen, Lise; MacDonald, David (2006-05-01). "Getting to grips with the magnitude of exploitation: Bushmeat in the Cross–Sanaga rivers region, Nigeria and Cameroon". Biological Conservation. 129 (4): 497–510. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2005.11.031. ISSN 0006-3207.

- ^ VICE (2017-12-20), Smoking Vulture Brains in South Africa, retrieved 2018-04-12

- ^ a b c d e McKean, S., Mander, M., Diederichs, N., Ntuli, L., Mavundla, K., Williams, V., & Wakelin, J. (2013). The impact of traditional use on vultures in South Africa. Vulture News, 65, 15-36.

- ^ a b Beilis, Nadine; Esterhuizen, Johan (2005-01-01). "The potential impact on Cape Griffon Gyps coprotheres populations due to the trade in traditional medicine in Maseru, Lesotho". Vulture News. 53 (1): 15–19. doi:10.4314/vulnew.v53i1.37630. ISSN 1606-7479.

- ^ Roxburgh, L.; McDougall, R. (2012-01-01). "Vulture Poisoning Incidents and the Status of Vultures in Zambia and Malawi". Vulture News. 62 (1): 33–39. doi:10.4314/vulnew.v62i1.3. ISSN 1606-7479.

- ^ Chiweshe, Ngoni (2007-09-01). The current conservation status of the Ground Hornbill Bucorvus leadbeateri in Zimbabwe. In: Kemp, A.C. & Kemp, M.I. (eds). The Active Management of Hornbills and their Habitats for conservation pp. 252-256.

- ^ K Bruyns, Robin; Williams, Vivienne; B Cunningham, Anthony (2013-11-14). Animals in Traditional Folk Medicine: Implications for Conservation. pp. 475–486. ISBN 9783642290251.

- ^ a b Anderson, Mark (2009-11-12). "Vulture crises in South Asia and West Africa … and monitoring, or the lack thereof, in Africa". Ostrich: Journal of African Ornithology. 78 (2): 415–416. doi:10.2989/OSTRICH.2007.78.2.47.127. S2CID 84365762.

- ^ a b c d e Williams, Vivienne L.; Cunningham, Anthony B.; Kemp, Alan C.; Bruyns, Robin K. (2014-08-27). "Risks to Birds Traded for African Traditional Medicine: A Quantitative Assessment". PLOS ONE. 9 (8): e105397. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9j5397W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0105397. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4146541. PMID 25162700.

- ^ a b Odino, Martin; Imboma, Titus; Ogada, Darcy L. (2014-01-01). "Assessment of the occurrence and threats to Hooded Vultures Necrosyrtes monachus in western Kenyan towns". Vulture News. 67 (2): 3–20. doi:10.4314/vulnew.v67i2.1. ISSN 1606-7479.

- ^ Gosler, Andrew (2010). Ethno-ornithology: Birds, Indigenous Peoples, Culture and Society. London: Earthscan. pp. 279–289. ISBN 9781844077830.

- ^ Thiollay, J. (2006). Severe decline of large birds in the Northern Sahel of West Africa: A long-term assessment. Bird Conservation International, 16(4), 353-365. doi:10.1017/S0959270906000487

- ^ a b c d e Nikolaus (2011). "The Fetish Culture in West Africa: An Ancient Tradition As A Threat to Endangered Birdlife?" (PDF). Tropical Vertebrates in a Changing World: 145–149. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- ^ Campbell, M. (2009). Factors for the presence of avian scavengers in Accra and Kumasi, Ghana. Area, 41(3), 341-349. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4762.2008.00870.x

- ^ Saale, L. B. (2017). Vulture significance in Ogoni Culture. AFRREV LALIGENS: An International Journal of Language, Literature and Gender Studies, 6(2), 104. doi:10.4314/laligens.v6i2.9

- ^ Adeola, M. (1992). Importance of Wild Animals and Their Parts in the Culture, Religious Festivals, and Traditional Medicine, of Nigeria. Environmental Conservation, 19(2), 125-134. doi:10.1017/S0376892900030605

- ^ Fourie, L (1996). "Poisoning of wildlife in South Africa". Journal of the South African Veterinary Association. 67 (2): 74–76. PMID 8765066.