Alexander Monro Primus

Alexander Monro | |

|---|---|

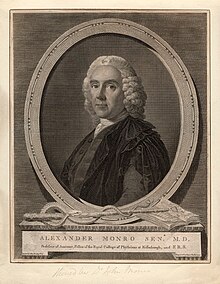

Alexander Monro primus by Allan Ramsay (1749) | |

| Born | 19 September 1697 London |

| Died | 10 July 1767 (aged 69) |

| Occupation | Professor of Anatomy |

| Known for | founder of Edinburgh Medical School |

Alexander Monro (19 September 1697 – 10 July 1767) was the founder of Edinburgh Medical School. To distinguish him as the first of three generations of physicians of the same name, he is known as primus.

Life

Monro was born of Scots parentage in London, and studied there, and at Paris and Leiden. He was appointed lecturer on Anatomy by the Surgeons' Company (now the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh) at Edinburgh in 1719; two years later he became professor, and in 1725 was admitted to the University. He was a principal promoter and early clinical lecturer in the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary, and continued his clinical work after resigning his chair to his son Alexander secundus.[1]

Alexander's father, John Munro took great pains with his education. He had him instructed in the Latin, Greek and French languages, philosophy, arithmetic and book-keeping. After having gone through the usual course at the University of Edinburgh, he was bound apprentice to his father, who was in extensive practice. In 1717 on completion of his apprenticeship, young Alexander Munro (primus) was sent to London to study anatomy under William Cheselden, the famous surgeon who was an enthusiastic teacher and a skilful demonstrator. A lasting friendship was formed between the two men.

To gain as much experience as possible Monro lodged in the house of an apothecary and visited patients with him, and he also attended lectures by Mr. Whiston and Mr Hawksby on experimental philosophy. He made dissections of the human body and of various animals, though his career was nearly cut short owing to a scratched hand being infected by the suppurated lung of a phthisical subject. Monro took an active part in discussions, and in one of his papers first sketched his "Account of the Bones in General". Before he left London he sent home to his father some of his anatomical specimens, and received the encouraging reply that on his return to Edinburgh, if he continued as he had begun, Mr Drummond would resign his share of the professorship of anatomy in his favour.

In the spring of 1718, Alexander Monro (primus) went to Paris where he walked the hospitals and attended a course of anatomy given by Bouquet. He performed operations under the direction of Thibaut and had instruction in midwifery from Gregoire, bandages from Cesau, and botany from Chomel. On 16 November 1718, Monro entered as a student of Leyden University to study under Boerhaave, the great physician, who lectured on the theory and practice of physic. Many patients from Scotland came to consult Boerhaave, and were put under Monro's care.[2]

On his return to Edinburgh in the autumn of 1719, young Monro was examined by the Incorporation of Surgeons and was admitted as a member on 19 November. Mr Drummond then fulfilled his promise of resigning his professorship, and Mr M'Gill did likewise. They also gave Monro a recommendation to the Town Council, the patrons of the University. This was backed by the Surgeons, and on 22 January 1720 the Council appointed him Professor of Anatomy with a salary of £15 sterling, this modest sum being supplemented by the students' fees of three guineas a head.

Monro's original appointment as professor was only at the pleasure of the Town Council, but in 1722, encouraged by his success, he applied for a permanent status, and although the council had as lately as August 1719 reaffirmed the principle that regentships and professor ships were to be held at their pleasure, nevertheless they departed from it and by resolution of 14 March 1722, nominated Alexander Monro sole Professor of Anatomy in the City and College. Monro was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society, on 27 June 1723'.

Until 1725, Monro continued to lecture in the old Surgeons' Hall on the south side of Surgeons' Square, but in that year he was granted a theatre in the University buildings. At the end of 1726, Monro published his "Anatomy of the Human Bones", which went through eight editions in his lifetime, the later ones including a treatise on the nerves. It was translated into most European languages and in 1759 a folio edition with elegant engravings was published in Paris by Mr Joseph Sue, Professor of Anatomy to the Royal Schools of Surgery and to the Royal Academy of Painting Sculpture. The great reputation attained by Monro's work did much to increase the fame of the new school of medicine on Edinburgh.[2] In 1764, he resigned his professorship, but continued to give clinical lectures at the hospital. In the same year, he published An Account of the Inoculation of Small-pox in Scotland.[3]

Like all three generations, primus was a Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh. Secundus and Tertius were also Presidents of the RCPE.

He died in Edinburgh of a pelvic cancer 10 July 1767.[2] He is buried in Greyfriars Kirkyard in the centre of Edinburgh with his wife and son, Alexander. The grave lies west of the church and north of the Adam mausoleum. It was recarved in the mid-19th century and is Victorian in style.

Family

In 1725, he married Isabella MacDonald (d.1774), third daughter of Sir Donald MacDonald of Sleat. They had a son Alexander Monro, (1733–1817).[2]

Works

- Osteology, A treatise on the anatomy of the human bones with An account of the reciprocal motions of the heart and A description of the human lacteal sac and duct — Online: the 1741 edition.

Notes

- ^

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Wood, James, ed. (1907). "Monro, Alexander". The Nuttall Encyclopædia. London and New York: Frederick Warne.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Wood, James, ed. (1907). "Monro, Alexander". The Nuttall Encyclopædia. London and New York: Frederick Warne.

- ^ a b c d Moore 1894.

- ^ "Extrait", book review in Journal de médecine, chirurgie, pharmacie, 1765, no. 23, p. 291 (French)

References

- Moore, Norman (1894). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 38. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- The Monros of Auchinbowie and Cognate Families. By John Alexander Inglis. Edinburgh. Printed privately by T and A Constable. Printers to His Majesty. 1911.