Ann Walker (landowner)

Ann Walker | |

|---|---|

| Born | 20 May 1803 |

| Died | 25 February 1854 (aged 50) |

| Resting place | St Matthew's Church, Lightcliffe, Wakefield Road, Lightcliffe |

| Nationality | British |

| Occupation(s) | Landowner, Philanthropist |

| Partner | Anne Lister (m. 1834; died 1840) |

Ann Walker (20 May 1803 – 25 February 1854) was an English landowner from West Riding of Yorkshire. She and her partner Anne Lister were the first known women to have a same-sex wedding ceremony, without legal recognition, at Holy Trinity Church, York in 1834.[1]

Early life

Ann Walker was born on 20 May 1803 in Lightcliffe, West Riding of Yorkshire to John and Mary Walker (née Edwards).[2] She was baptised at St Matthew's Church, Lightcliffe and lived her early years at Cliffe Hill with her parents, sisters Mary and Elizabeth, and brother John, until her family moved to Crow Nest when she was six years old.[3] Ann's sister Mary died in 1815, Ann was 19 when her father died on 29 April 1823, and her mother died later that same year on 20 November 1823, when Ann was 20. Ann's younger brother John inherited Crow Nest, the family's estate. At the end of October 1828, Ann's sister Elizabeth married Captain George Mackay Sutherland and moved to Ayrshire.[4] Subsequently, after the death of her brother John in 1830, Ann and her sister Elizabeth became sole inheritors of the Crow Nest Estate, offering significant wealth.[5] Ann continued to live on the Crow Nest estate through her 20s, until 1831-1832 when she moved into Lidgate, a smaller home on the estate. It was at Lidgate that Anne Lister began to court Ann Walker after a re-acquaintance on 6 July 1832.[6]

Marriage

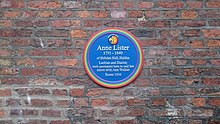

Ann Walker and Anne Lister lived on nearby estates for several years, and met on occasion.[7] However, it wasn't until 1832 that the pair became involved in a romantic and sexual relationship.[8] This relationship intensified over the next few months and, on 27 February 1834, Ann Walker exchanged rings with Anne Lister as a symbol of their commitment to one another.[9] They took communion together in Holy Trinity Church, Goodramgate, York on Easter Sunday (30 March) in 1834 to seal their union, considering themselves married.[10] The building now displays a commemorative blue plaque.[11] Following the ceremony, they lived together at Shibden Hall, Anne Lister's ancestral home. The couple travelled widely together until Anne Lister's untimely death in Georgia in 1840.[12] Ann Walker had Anne's body embalmed and Walker spent 6 months travelling back to England so that Anne could be interred in the Lister family vault in Halifax.[13] Anne Lister's will gave Ann Walker a life interest in Shibden Hall and its estate.

Faith and philanthropy

Ann Walker's Christian faith was incredibly important to her, as were her philanthropic endeavours. She worshipped regularly at St Matthews Church in Lightcliffe throughout her life, and would also read prayers and scripture to her family and servants on Sundays.[14] Ann created her own Sunday school for children,[15] whom she was always very fond of. She also took great care of her servants, as is evidenced by a letter written back home while she was travelling abroad in 1840, where she lists out the gifts that each of them should be given for Christmas in her absence.[16]

Mental health

Ann Walker struggled with mental health issues throughout her life. She was prone to bouts of depression and possibly psychosis, which appeared in part to be linked to her religious faith.[17] In 1843, three years after the death of Anne Lister, she was declared to be of 'unsound mind' and forcibly removed from Shibden Hall to an asylum in York. She later moved back to her family's estate in Lightcliffe, living at Cliffe Hill until her death in 1854.[18]

Death

Ann Walker died on 25 February 1854, aged 50. As per her death certificate, her cause of death is recorded as 'congestion of the brain effusion'. She is buried in St Matthew's Churchyard, Lightcliffe alongside her aunt, also named Ann Walker.[19] The original St Matthew's church was demolished and rebuilt in a different location in Lightcliffe, but the tower of the original church still remains. Ann's original brass memorial plaque now hangs in this tower. A special public viewing of this memorial plaque took place on Saturday, 14 September 2019 when the tower was unlocked for the first time since its closure in the 1970's.[20]

Legacy

No known portraits of Ann Walker exist, but a few of her letters are held in the West Yorkshire Archives. Much of what is known about Ann Walker comes from the journals of Anne Lister, who kept detailed diaries throughout her adult life. It's known that Ann Walker kept a journal too, yet none have ever been found. It is likely that many of her possessions were destroyed, as her relationship with Anne Lister was considered shameful to the extended Walker family. Ann Walker's legacy lives on today. Her courage, resolve and mental health struggles have inspired many. Ann lived against her family's wishes and chose a life with Anne Lister.

Fundraising has taken place to have a publicly displayed plaque for Ann Walker to recognise her life and her historical significance to the LGBT community. In addition, The Ann Walker Memorial Foundation has been created in Ann's name, which raises funds for charities working with LGBT youth and those with mental health issues, to create a lasting legacy in her name.[21]

References

- ^ Correspondent, Harriet Sherwood Religion (28 July 2018). "Recognition at last for Gentleman Jack, Britain's 'first modern lesbian'". The Observer. ISSN 0029-7712. Retrieved 11 November 2019.

- ^ Liddington, Jill (1998). Female Fortune: Land, Gender and Authority: The Anne Lister Diaries and Other Writings, 1833–36. Rivers Oram Press. p. 30. Retrieved 11 November 2019.

- ^ Liddington, Jill (1998). Female Fortune: Land, Gender and Authority: The Anne Lister Diaries and Other Writings, 1833–36. Rivers Oram Press. p. 31. Retrieved 11 November 2019.

- ^ Liddington, Jill (1998). Female Fortune: Land, Gender and Authority: The Anne Lister Diaries and Other Writings, 1833–36. Rivers Oram Press. p. 35. Retrieved 11 November 2019.

- ^ Liddington, Jill (1998). Female Fortune: Land, Gender and Authority: The Anne Lister Diaries and Other Writings, 1833–36. Rivers Oram Press. p. 36. Retrieved 11 November 2019.

- ^ Liddington, Jill, 1946- (2003). Nature's domain : Anne Lister and the landscape of desire. Hebden Bridge, West Yorkshire: Pennine Pens. ISBN 1873378483. Retrieved 11 November 2019.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Whitbread, Helena (2012). The Secret Diaries of Miss Anne Lister. Virago Press. pp. 24, 115, 117, 138, 169, 170, 206, 355. ISBN 978-1844087198. Retrieved 11 November 2019.

- ^ Liddington, Jill, 1946- (2003). Nature's domain : Anne Lister and the landscape of desire. Hebden Bridge, West Yorkshire: Pennine Pens. ISBN 1873378483. Retrieved 11 November 2019.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Choma, Anne (2019). Gentleman Jack: The Real Anne Lister. PenguinRandomhouse. p. 306. ISBN 9780143134565. Retrieved 11 November 2019.

- ^ Choma, Anne (2019). Gentleman Jack: The Real Anne Lister. PenguinRandomhouse. p. 311. ISBN 9780143134565. Retrieved 11 November 2019.

- ^ "Anne Lister: Reworded York plaque for 'first lesbian' - BBC News". BBC News. 28 February 2019. Retrieved 10 November 2019.

- ^ Liddington, Jill (1998). Female Fortune: Land, Gender and Authority: The Anne Lister Diaries and Other Writings, 1833–36. Rivers Oram Press. p. 273. Retrieved 11 November 2019.

- ^ Choma, Anne (2019). Gentleman Jack: The Real Anne Lister. PenguinRandomhouse. p. 313. ISBN 9780143134565. Retrieved 11 November 2019.

- ^ Euler, Catherine (1995). Moving Between Worlds: Gender, Class, Politics, Sexuality and Women's Networks in the Diaries of Anne Lister of Shibden Hall, Halifax, Yorkshire, 1830-1840 (PhD). University of York. p. 209.

- ^ Liddington, Jill (1998). Female Fortune: Land, Gender and Authority: The Anne Lister Diaries and Other Writings, 1833–36. Rivers Oram Press. p. 286. Retrieved 11 November 2019.

- ^ Letter from Ann Walker to Booth, 17 December 1840. Stored at West Yorkshire Archives, ref: SH:7/LL/406. Transcribed by Anne Choma July 2019.

- ^ Choma, Anne (2019). Gentleman Jack: The Real Anne Lister. PenguinRandomhouse. p. 62. ISBN 9780143134565. Retrieved 11 November 2019.

- ^ Choma, Anne (2019). Gentleman Jack: The Real Anne Lister. PenguinRandomhouse. p. 313. ISBN 9780143134565. Retrieved 11 November 2019.

- ^ Barker, D.M. (2018). "The Walkers of Crow Nest" (PDF). www.lightcliffehistory.org.uk. Retrieved 11 November 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "A rare opportunity". Friends of Friendless Churches. Retrieved 11 November 2019.

- ^ The Ann Walker Memorial Foundation (2019) http://www.annwalkermemorialfoundation.org/

Sources

- Choma, Anne, "Gentleman Jack: The Real Anne Lister". Retrieved 11 November 2019. (PenguinRandomhouse, 2019)

- Euler, Catherine, "Moving Between Worlds: Gender, Class, Politics, Sexuality and Women's Networks in the Diaries of Anne Lister of Shibden Hall, Halifax, Yorkshire, 1830-1840". Retrieved 11 November 2019. (University of York, 1995)

- Liddington, Jill, "Female Fortune: Land, Gender and Authority: The Anne Lister Diaries and Other Writings, 1833–36". Retrieved 11 November 2019. (Rivers Oram Press, 1998)

- Liddington, Jill, "Nature´s domain : Anne Lister and the landscape of desire". Retrieved 11 November 2019. (Pennine Pens Press, 2003)

- Whitbread, Helena, "The Secret Diaries of Miss Anne Lister". Retrieved 11 November 2019. (Virago Press, 2012)