Call and response (music)

In music, call and response is a compositional technique, often a succession of two distinct phrases that works like a conversation in music. One musician offers a phrase, and a second player answers with a direct commentary or response. The phrases can be vocal, instrumental, or both.[1] Additionally, they can take form as commentary to a statement, an answer to a question or repetition of a phrase following or slightly overlapping the initial speaker(s).[2] It corresponds to the call and response pattern in human communication and is found as a basic element of musical form, such as the verse-chorus form, in many traditions.

By region

[edit]Africa

[edit]In Sub-Saharan African cultures, call and response is a pervasive pattern of democratic participation—in public gatherings in the discussion of civic affairs, in religious rituals, as well as in vocal and instrumental musical expression. Most of the call and response practices found in modern culture originated in Sub-Saharan Africa. [3]

North America

[edit]Enslaved Africans brought call and response music with them to the colonized American continents and it has been transmitted over the centuries in various forms of cultural expression—in religious observance, public gatherings, sporting events, children's rhymes, and most notably, in African-American music in its myriad forms and descendants. These include soul, gospel, blues, rhythm and blues, rock and roll, funk, pop, and hip hop. Hear for example the recordings entitled "Negro Folklore from Texas State Prisons" collected by Bruce Jackson on an Electra Records recording.[4] Call and response are widely present in parts of the Americas touched by the trans-Atlantic slave trade. The tradition of call and response fosters dialogue and its legacy continues today, as it is an important component of oral traditions. Both African-American women work songs, African American work songs, and the work song, in general, use the call-and-response format often. It can also be found in the music of the Afro-Caribbean populations of Jamaica, Trinidad & Tobago, Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, and many nations of the diaspora, especially Brazil.

Call and response is extensively used in Cuban music, where it is known as coro-pregón. It derives from African musical elements, both in the secular rumba[5] and in African religious ceremonies (Santería).[6]

South America

[edit]When enslaved African populations were brought to work in coastal agricultural areas of Peru during colonial times, they brought along their musical traditions. In Peru, those traditions mixed with Spanish popular music of the nineteenth century, as well as the indigenous music of Peru, eventually growing into what is commonly known as Afro-Peruvian music. Known as “huachihualo“, and characterized by competitive call-and-response verses, it is the defining trademark of various musical styles in Afro-Peruvian musical culture such as marinera, festejo, landó, tondero, zamacueca, and contrapunto de zapateo[7]

In Colombia, the dance and musical form of cumbia originated with the enslaved African population of the coastal region of the country in the late 17th century. The style developed in Colombia from the intermingling of three cultures. From Africa, the drum percussion, foot movements and call-and-response. Its melodies and use of the gaita or caña de millo (cane flute) represents the Native Colombian influence, and the dress represents the Spanish influence.[8][9]

United Kingdom

[edit]In 1644, lining out – where one person sang a solo (a precentor) and others followed – is outlined by the Westminster Assembly for psalm singing in English churches.[10] It has influenced popular music singing styles.[10] Presentinge line was characterized a slow, drawn-out heterophonic and often profusely ornamented melody, while a clerk or precentor (song leader) chanted the text line by line before it was sung by the congregation. Scottish Gaelic psalm-singing by prepresentinge line was the earliest form of congregational singing adopted by Africans in America.[11]

Call and response is also a common structure of songs and carols originating in the Middle Ages, for example "All in the Morning" and "Down in yon Forest", both traditional Derbyshire carols.[12]

Classical music

[edit]In Western classical music, call and response is known as antiphony. The New Grove Dictionary defines antiphony as "music in which an ensemble is divided into distinct groups, used in opposition, often spatial, and using contrasts of volume, pitch, timbre, etc."[13] Early examples can be found in the music of Giovanni Gabrieli, one of the renowned practitioners of the Venetian polychoral style:

Gabrieli also contributed many instrumental canzonas, composed for contrasting groups of players:

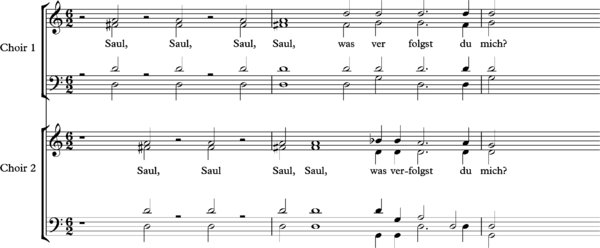

Heinrich Schütz was one of the first composers to realise the expressive potential of the polychoral style in his "Little Sacred Concertos". The best known of these works is "Saul, Saul, was verfolgst du mich?", a vivid setting of the narrative of the Conversion of Paul as told in Acts 9 verses 3-4: "And as he journeyed, he came near Damascus: and suddenly there shined round about him a light from heaven. And he fell to the earth, and heard a voice saying unto him, Saul, Saul, why persecutest thou me?"

"The musical phrase on which most of the concerto is built is sounded immediately by a pair of basses":[14]

This idea is "then taken up by the alto and tenor, then by the sopranos, and finally by the pair of violins as transition to the explosive tutti":[14]

"The syncopated repetitions of the name Saul are strategically planted so that, when the whole ensemble takes them up, they can be augmented into hockets resounding back and forth between the choirs, adding to the impression of an enveloping space And achieving in sound something like the effect of the surrounding light described by the Apostle."[15]

In the following century, J.S. Bach featured antiphonal exchanges in his St Matthew Passion and the motets. In his motet Komm, Jesu, komm, Bach uses eight voices deployed as two antiphonal choirs. According to John Eliot Gardiner, in this "intimate and touching" work, Bach “goes many steps beyond the manipulation of spatially separate blocks of sound” and “finds ways of weaving all eight lines into a rich contrapuntal tapestry.”[16]

The development of the classical orchestra in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries exploited the dramatic potential of antiphonal exchanges between groups of instruments. An example can be found in the development section of the finale of Mozart’s Symphony No. 41:

Even terser are the exchanges between wind and strings in the first movement of Beethoven's 5th Symphony. Here, the development culminates in a "singularly dramatic passage"[17] consisting of a "strange sequence of block harmonies":[18]

Twentieth century works that feature antiphonal exchanges include the second movement of Béla Bartók's Music for Strings Percussion and Celesta (1936) and Michael Tippett’s Concerto for Double String Orchestra (1938). One spectacular example from the 1950s is Karlheinz Stockhausen's Gruppen for Three Orchestras (1955–1957), which culminates in a "synchronized build-up of brass 'points' in the three orchestras ... leading to a climax of chord exchanges from orchestra to orchestra".[19] When heard live, this piece creates a genuine sensation of music moving in space. "The combination of the three orchestras leads to great climaxes: long percussion solos, concertante trumpet solos, powerful brass sections, alternating and interpenetrating."[20]

Popular music

[edit]Call and response is common in modern Western popular music. Cross-over rhythm and blues, rock 'n' roll and rock music exhibit call-and-response characteristics, as well. The Who's song "My Generation" is an example:[21]

Leader/chorus call and response

[edit]A single leader makes a musical statement, and then the chorus responds together. American bluesman Muddy Waters utilizes call and response in one of his signature songs, "Mannish Boy" which is almost entirely leader/chorus call and response.

CALL: Waters' vocal: "Now when I was a young boy"

RESPONSE: (Harmonica/rhythm section riff)

CALL: Waters': "At the age of 5"

RESPONSE: (Harmonica/rhythm section riff)

Another example is from Chuck Berry's "School Day (Ring Ring Goes the Bell)".

CALL: Drop the coin right into the slot.

RESPONSE: (Guitar riff)

CALL: You gotta get something that's really hot.

RESPONSE: (Guitar riff)

A contemporary example is from Carly Rae Jepsen's "Call Me Maybe".

CALL: Hey, I just met you

RESPONSE: (Violins)

CALL: And this is crazy

RESPONSE: (Violins)

This technique is utilized in Jepsen's song several times. While mostly in the chorus, it can also be heard in the breakdown (approximately 2:25) between the vocals ("It's hard to look right") and distorted guitar.

Question/answer call and response

[edit]Part of the band poses a musical "question", or a phrase that feels unfinished, and another part of the band "answers" (finishes) it. In the blues, the B section often has a question-and-answer pattern (dominant-to-tonic).

An example of this is the 1960 Christmas song "Must Be Santa":

CALL: Who laughs this way, ho ho ho?

RESPONSE: Santa laughs this way, ho ho ho!

A similar question-and-answer exchange occurs in the 1942 film Casablanca between Sam (Dooley Wilson) and the band in the song "Knock On Wood":

CALL: Who's got trouble?

RESPONSE: We've got trouble!

CALL: How much trouble?

RESPONSE: Too much trouble!

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Call and Response - The Sound of Collaboration | Institute for the Study of Knowledge Management in Education". www.iskme.org. Archived from the original on Oct 31, 2023. Retrieved 2023-10-31.

- ^ "What is Call and Response in Music?". MasterClass. August 26, 2021.

- ^ Courlander, Harold, A Treasury of Afro-American Folklore: The Oral Literature, Traditions, Recollections, Legends, Tales, Songs, Religious Beliefs, Customs, Sayings and Humor of People of African Descent in the Americas. New York: Marlowe & Company, 1976.

- ^ "Negro Folklore from Texas State Prisons - YouTube". YouTube. Archived from the original on 2020-04-01. Retrieved 2017-06-22.

- ^ Orovio, Helio 2004. Cuban music from A to Z. Revised by Sue Steward. ISBN 0-8223-3186-1 A biographical dictionary of Cuban music, artists, composers, groups and terms. Duke University, Durham NC; Tumi, Bath. p191

- ^ Sublette, Ned 2004. Cuba and its music: from the first drums to the mambo. Chicago. ISBN 1-55652-516-8

- ^ "Afro-Peruvian Music and Dance". Music.si.edu. 29 July 2015. Archived from the original on Feb 19, 2024. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

- ^ "Everything you need to know about Cumbia". Colombia.co. 27 July 2015. Archived from the original on Jan 27, 2024. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

- ^ "Cumbia | The Rhythm of Colombia". discovercolombia.com. Archived from the original on 2011-12-03.

- ^ a b Shepherd, John (2003). Continuum Encyclopedia of Popular Music of the World: VolumeII: Performance and Production, Volume 11. A&C Black. p. 146.

- ^ "From Charles Mackintosh's waterproof to Dolly the sheep: 43 innovations Scotland has given the world". The independent. January 3, 2016. Archived from the original on Jan 20, 2024.

- ^ Russel, Ian (2012). The Derbyshire Book Of Village Carols. Sheffield: Village Carols. p. 2.

- ^ "Antiphony", article in the New Grove Dictionary of Music (2001). Oxford University Press.

- ^ a b Taruskin, R. (2005, p. 69) The Oxford History of Western Music; the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Taruskin, R. (2005, p. 68-69) The Oxford History of Western Music; the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Gardiner, J. E. (2013, p.470) Music in the Castle of Heaven: a Portrait of Johan Sebastian Bach. London, Allen Lane.

- ^ Grove, G. (1898, p.153) Beethoven and his Nine Symphonies. London, Constable.

- ^ Hopkins, A. (1981, p.137) The Nine Symphonies of Beethoven. London, Heinemann.

- ^ Maconie, R. (1976, p. 111) The Works of Stockhausen. London, Marion Boyars.

- ^ Worner, K. H. (1973). Stockhausen: Life and Work. London, Faber. p.163

- ^ a b Middleton, Richard (1990). Studying Popular Music. Milton Keynes, UK: Open University Press. ISBN 0-335-15275-9. p. 49.

External links

[edit]- Call and Response in Blues—with references to blues songs and historical evolution.

- History of Gospel Music—with references to call and response in black gospel music

- Gospel Music History—Gospel Music Encyclopedia citing the origins of the different types of call and response and different gospel music style