Antiviral (film)

| Antiviral | |

|---|---|

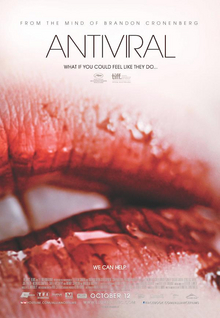

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Brandon Cronenberg |

| Written by | Brandon Cronenberg |

| Produced by | Niv Fichman |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Karim Hussain |

| Edited by | Matthew Hannam |

| Music by | E.C. Woodley |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by |

|

Release dates | |

Running time | 108 minutes |

| Countries |

|

| Language | English |

| Budget | C$3.3 million[2] |

| Box office | $123,407[3] |

Antiviral is a 2012 science fiction horror film written and directed by Brandon Cronenberg. The film competed in the Un Certain Regard section at the 2012 Cannes Film Festival.[4][5] Cronenberg re-edited the film after the festival to make it tighter, trimming nearly six minutes out of the film. The revised film was first shown at the 2012 Toronto International Film Festival,[6] and was a co-winner, alongside Jason Buxton's Blackbird, of the festival's Best Canadian First Feature Film award.[7]

Plot

[edit]Syd March is employed by the Lucas Clinic, a company which purchases viruses and other pathogens from celebrities who fall ill, in order to inject them into clients who desire a connection with celebrities. In particular, the pathogens supplied by the Lucas Clinic's exclusive celebrity Hannah Geist are extremely popular, and another employee at the clinic, Derek Lessing, is responsible for harvesting them from Hannah directly. To make extra money, Syd uses his own body as an incubator, steals pathogens from the lab, and sells them on the black market. To do so, he uses a stolen console to break the copy protection placed on the virus by the clinic; once injected in a client, the pathogen is rendered incommunicable. He then passes the pathogens to Arvid, who works at Astral Bodies, a celebrity meat market where meat is grown from the cells of celebrities for consumption.

After Derek is caught smuggling and arrested, Lucas asks Syd to take his place and harvest a pathogen from Hannah, who has recently fallen ill. Once he has taken a blood sample from Hannah, Syd quickly injects himself with some of her blood. He experiences the first symptoms, fever and disorientation, rapidly, and he leaves work early. His attempts to remove the virus' copy protection are unsuccessful, and his console breaks down during the process. When Syd awakens from severe delirium the next day, he discovers Hannah has died from the unknown disease, and all products harvested from her have skyrocketed in popularity. Desperate to fix his console, he approaches Arvid, who sets up a meeting with Levine, the leader of the piracy group. Levine offers to fix the console in exchange for samples of Syd's blood, but Syd refuses. Levine subdues him and forcibly takes samples from Syd, as the pathogen which killed Hannah is now hotly in demand on the black market, and lethal pathogens are not legal to distribute.

The next day, a severely ill Syd is approached by two men, who drive him to an undisclosed location where Hannah is actually still alive. Syd learns from Hannah's physician Dr. Abendroth that the virus infecting them both has been intentionally engineered with a security measure to prevent analysis, which explains why Syd's console was destroyed. Hannah's death was fabricated to protect her, but she is shown to be in the extreme stages of the illness, extremely weak and bleeding from her mouth. Dr. Abendroth reveals to Syd that the virus is a modified version of an illness that Hannah has had before, and that he himself has an infatuation with her, having had samples of her skin grafted to his own arm. He further suggests that since Syd unnecessarily injected himself with Hannah's blood, he too is "just another fan." As Syd's condition worsens, he returns to the Lucas Clinic, where he traces the original strain of the virus to Derek, who sold it to a rival company, Vole & Tesser. Dr. Abendroth discovers that Vole & Tesser patented the modified strain, though their motives remain unclear.

Before Syd can proceed further, he is abducted by Levine and incarcerated in a room where his deterioration and death will be broadcast on reality television to sate Hannah's fans, who could not witness her death. As Syd begins to show the final symptoms, he escapes by spearing Levine in the mouth with a syringe and holding a nurse hostage with his infected blood. After Syd realizes that Vole & Tesser infected Hannah to harvest their own patented pathogen from her, Syd contacts Tesser and negotiates a deal. The film closes with a virtual reality version of Hannah that advertises her "Afterlife" exclusively from Vole & Tesser. Syd is shown working for Vole & Tesser, where Hannah's cells have been replicated to form a distorted cell garden from Astral Bodies' celebrity meat technology. Viruses injected into her system are sold. Syd demonstrates a new virus as he sticks a needle into a genetically created arm. Later, while alone, Syd cuts the arm and drinks the flowing blood; it is revealed the arm is in fact Hannah's, as her deformed face and body are shown to be in the Cell Garden chamber.

Cast

[edit]- Caleb Landry Jones as Syd March, an employee at Lucas Clinic

- Sarah Gadon as Hannah Geist, a world-class celebrity

- Malcolm McDowell as Dr. Abendroth, Hannah Geist's personal medic

- Douglas Smith as Edward Porris, a customer of Lucas Clinic

- Joe Pingue as Arvid, the owner of the Astral Bodies meat market and underground virus trafficker

- Nicholas Campbell as Dorian Lucas, the founder and owner of Lucas Clinic

- Sheila McCarthy as Dev Harvey, Hannah Geist's manager

- Wendy Crewson as Mira Tesser, co-owner of Vole & Tesser, Lucas Clinic's main competitor

- James Cade as Levine, an underground virus trafficker

- Lara Jean Chorostecki as Michelle, Lucas Clinic's archivist

- Lisa Berry as the Lucas Clinic receptionist [8][9]

- Salvatore Antonio as Topp, an employee at Lucas Clinic

- Matt Watts as Mercer, an employee at Lucas Clinic

- Reid Morgan as Derek Lessing, an employee at Lucas Clinic

- Nenna Abuwa as Aria Noble, the second main celebrity in Lucas Clinic's catalogue

- George Tchortov as Portland

Production

[edit]Cronenberg has stated that the genesis of the film was a viral infection he once had. More precisely, the "central idea came to him in a fever dream during a bout of illness," wrote journalist Jill Lawless.[10] Cronenberg said:

I was delirious and was obsessing over the physicality of illness, the fact that there was something in my body and in my cells that had come from someone else's body, and I started to think there was a weird intimacy to that connection. And afterwards I tried to think of a character who would see a disease that way and I thought: a celebrity-obsessed fan. Celebrity culture is completely bodily obsessed - who has the most cellulite, who has fungus feet? Celebrity culture completely fetishizes the body and so I thought the film should also fetishize the body - in a very grotesque way.[11]

It was further shaped when he saw an interview Sarah Michelle Gellar did on Jimmy Kimmel Live!; what struck him was when "she said she was sick and if she sneezed she'd infect the whole audience, and everyone just started cheering."[12]

Principal photography took place in Hamilton, Ontario and in Toronto.[13]

Reception

[edit]Rotten Tomatoes reports that 65% of critics gave the film a positive review with an average score of 6/10, based on 93 reviews. The site's consensus reads, "Antiviral is a well crafted body horror, packed with interesting - if not entirely subtle - ideas."[14] It holds a score of 55 out of 100 on review aggregator Metacritic, based on 18 reviews.[15]

Writing for The Daily Telegraph, Tim Robey gives the film 4 stars, calling it "an eye-widening delve into conceptual science fiction," with the "gruesome verve" of his father David Cronenberg's early work, "and morbidity to match", and says "there's real muscle in its ideas, a potent kind of satirical despair, and a level of craft you rarely expect from a first-timer."[16]

Writing for Empire, Kim Newman called it "a smart, subversive but rather cold debut".[17] Variety's Justin Chang stated that Brandon Cronenberg "has his own distinct flair for the grotesque", but that "the film suffers from basic pacing issues" and that "Antiviral never builds the sort of character investment or narrative momentum that would allow its visceral horrors to seriously disturb."[18] Stephen Garrett of The New York Observer described the film as "stomach-churning" and added that "the production, though impeccably polished and featuring an abundance of blood, spit, mucus, and pus, misses the mark with underdeveloped characters and a schematic plot. But boy, do those gory ideas and notions linger in the mind."[19]

Peter Bradshaw of The Guardian was more negative, stating that "Brandon Cronenberg's movie is made with some technical skill and focus, but it is agonisingly self-regarding and tiresome."[20]

References

[edit]- ^ "Screenings of May 19th". Festival de Cannes. 21 May 2012. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- ^ MacDonald, Gayle (6 September 2012). "Brandon Cronenberg Finds Inspiration in the Flu". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- ^ "Antiviral (2013)". The Numbers. Retrieved 22 January 2019.

- ^ "2012 Official Selection". Festival de Cannes. 5 November 2015 [5 May 2012]. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ^ "Cannes Seeing double Cronenbergs". Toronto Sun. 19 April 2012. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- ^ Kirkland, Bruce (9 September 2012). "Brandon Cronenberg Brings First Feature Film 'Antiviral' Home". Toronto Sun. Retrieved 11 September 2012.

- ^ Nemetz, Andrea (17 September 2012). "Chester filmmaker wins TIFF award for Blackbird". The Chronicle Herald. Archived from the original on 11 March 2014. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- ^ "Antiviral". filmaffinity.com. 2012.

- ^ Lawless, Jill (22 May 2012). "Brandon Cronenberg Is a Chip off the Bloody Block". Sioux City Journal. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ^ "Cronenbergs Bring Father-Son Story to Cannes: Brandon Cronenberg's Antiviral a Genre Film Like Father's Early Work". CBC News. 22 May 2012. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ^ Johnson, Ron (September 2012). "Time for Cronenberg 2.0". Post City Magazines (September 2012). Retrieved 11 September 2012.

- ^ Etan, Vlessing (3 November 2011). "Sarah Gadon, Malcolm McDowell Join 'Antiviral'". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 23 August 2013.

- ^ "Antiviral". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 3 October 2019.

- ^ "Antiviral". Metacritic. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- ^ Robey, Tim (31 January 2013). "Antiviral, review". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 22 January 2019.

- ^ Newman, Kim. "Antiviral". Empire. Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- ^ Chang, Justin (20 May 2012). "Antiviral". Variety. Retrieved 9 April 2012.

- ^ Garrett, Stephen (21 May 2012). "Son of Cronenberg Debuts Freak-fest Antiviral in Cannes". The New York Observer. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ^ Bradshaw, Peter (22 May 2012). "Cannes 2012: Antiviral – review". The Guardian. Retrieved 9 April 2013.

External links

[edit]- Antiviral at IMDb

- Antiviral at AllMovie

- Antiviral at Rotten Tomatoes

- Antiviral at Metacritic

- 2012 films

- 2012 directorial debut films

- 2012 horror thriller films

- 2012 independent films

- 2012 science fiction films

- 2010s Canadian films

- 2010s English-language films

- 2010s French films

- 2010s dystopian films

- 2010s science fiction horror films

- 2010s science fiction thriller films

- Biopunk films

- Canadian body horror films

- Canadian horror thriller films

- Canadian independent films

- Canadian science fiction horror films

- Canadian science fiction thriller films

- English-language Canadian films

- English-language French films

- English-language independent films

- Films about cannibalism

- Films about fandom

- Films about virtual reality

- Films directed by Brandon Cronenberg

- Films set in the future

- Films set in Toronto

- Films shot in Hamilton, Ontario

- Films shot in Toronto

- French horror thriller films

- French independent films

- French science fiction horror films

- French science fiction thriller films

- English-language science fiction horror films

- English-language horror thriller films

- English-language science fiction thriller films