Aquatic warbler

| Aquatic warbler | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Acrocephalidae |

| Genus: | Acrocephalus |

| Species: | A. paludicola

|

| Binomial name | |

| Acrocephalus paludicola (Vieillot, 1817)

| |

| |

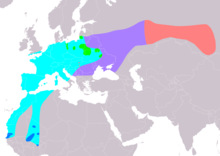

| Range of A. paludicola Breeding Passage Non-breeding Possibly Extant (passage) Probably extinct

| |

The aquatic warbler (Acrocephalus paludicola) is an Old World warbler in the genus Acrocephalus. It breeds in temperate eastern Europe and western Asia, with an estimated population of 11,000-15,000 pairs.[2] It is migratory, wintering in west Africa. After many years of uncertainty, the wintering grounds of much of the European population were finally discovered in Djoudj National Bird Sanctuary, Senegal, with between 5,000 and 10,000 birds present at this single site.[3] Its south-westerly migration route means that it is regular on passage as far west as Great Britain and Ireland.

This small passerine bird is a species found in wet sedge beds with vegetation shorter than 30 cm (12 in). Drainage has meant that this species has declined, and its stronghold is now the Polesie region of eastern Poland and south Belarus, where 70% of the world's population breeds. 3–5 eggs are laid in a nest in low vegetation. This species is highly promiscuous, with most males and females having offspring with multiple partners.[4]

This is a medium-sized warbler. The adult has a heavily streaked brown back and pale underparts with variable streaking. The forehead is flattened, and the bill is strong and pointed. There is a prominent whitish supercilium and crown stripe.

It can be confused with the juvenile sedge warbler, which may show a crown stripe, but the marking is stronger in this species, which appears paler and spiky-tailed in flight. The sexes are identical, as with most warblers, but young birds are unstreaked on the breast below. Like most warblers, it is insectivorous, but will take other small food items, including berries.

The song is a fast, chattering ja-ja-ja punctuated with typically acrocephaline whistles.

The genus name Acrocephalus is from Ancient Greek akros, "highest", and kephale, "head". It is possible that Naumann and Naumann thought akros meant "sharp-pointed". The specific paludicola is Latin, from paludis, "swamp", and colere, "to inhabit".[5]

Conservation

[edit]The aquatic warbler is the rarest and the only internationally threatened passerine bird found in mainland Europe. Apart from a very small remnant population in Western Siberia, its breeding grounds are completely confined to Europe.

The main threat the species is facing is the loss/degradation of habitat due to draining of wetlands, the decline of traditional, extensive agriculture and overgrowing of the species' habitat with reeds and bushes or trees. Under the auspices of the Convention on Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS), also known as the Bonn Convention, the Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) concerning Conservation Measures for the Aquatic Warbler was concluded and came into effect on 30 April 2003. The MoU covers 22 range States (Belarus, Belgium, Bulgaria, France, Germany, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Mali, Mauritania, Morocco, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Russian Federation, Senegal, Slovakia, Spain, Switzerland, Ukraine and United Kingdom). As of August 2012, 16 range States have signed the MoU. This instrument provides the basis for governments, NGO's and scientists to work together to save the species and their habitat.

Much of the funding for habitat protection for this species has come from the EU's LIFE programme.[6]

Conservation methods

[edit]The main method employed to protect the species from extinction is habitat restoration. Bushes, reeds and trees are cut down. An adequate level of water regulation is achieved through hydraulic equipment installation.[7]

In order to protect the bird's offspring, farmers need to select optimal grassland mowing time (as late as 15 of August) and choose environment-friendly mowing technologies. As the late-cut grass isn't suitable for feeding making these measures economically unfavorable, farmers who agree to help out receive state issued compensations. The unusable late-cut grass is taken to processing plants that recycle it into biofuel/grass pellets.[8]

Translocations

[edit]Due to small and fragmented populations of aquatic warbler within Lithuania, translocation to the Žuvintas biosphere reserve in Lithuania became necessary as a method to reverse declining genetic diversity in the region.[9]

During the species' first translocation In June 2018, the Lithuanian Baltic Environmental Forum (BEF) successfully translocated, raised, and released 49 aquatic warbler chicks from Zvanec Belarus to the Žuvintas biosphere reserve in Lithuania.[10] By the end of the 2019 summer breeding season, 11 (22%) of the translocated birds returned to the Žuvintas biosphere reserve.[11]

In the summer of 2019, the BEF successfully translocated, raised, and released an additional 50 birds from Zvanec Belarus to the Žuvintas biosphere reserve.[12]

Range and population

[edit]| Country/region and population group | Mean population estimate (singing males) | Population trend, comments |

|---|---|---|

| Central European | 10,769 | Decreasing/fluctuating |

| Belarus | 4,120 | Decreasing |

| Ukraine | 3,653 | Fluctuating, but data quality low |

| East-Poland | 2,996 | Increasing |

| Lithuanian | 110 | Fluctuating with recent increase |

| Lithuania | 110 | Strong decline until 2013, increase afterwards |

| Latvia | 0 | Last breeding season records 2000-2002 |

| Hungarian | 65 | No bird recorded since 2011 |

| Hungary | 65 | Steep decline until 2010 to 15-18 s.m., no bird recorded since 2011 |

| Pomeranian | 30 | Declining |

| West-Poland | 28 | Strong continuous decline since mid-1990s |

| Germany | 2 | Strong decline since early 19th century, 0-10 s.m. 2007–10, 3 s.m. in 2010, 3 s.m. in 2012, 1 s.m. in 2013, absent since 2014 |

| Siberian | 0-500 | Unknown |

| Russia (western Siberia) | 0-500 | Last breeding season records from 2000 (western Siberia), possibly now extinct |

| Global population | 10,974 | Stable/fluctuating but small geographical subpopulations all declining |

References

[edit]- ^ BirdLife International (2017). "Acrocephalus paludicola". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017: e.T22714696A110042215. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-1.RLTS.T22714696A110042215.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ a b Tanneberger, Franziska; Kubacka, Justyna (2018). The Aquatic Warbler Conservation Handbook. Groß Glienicke: Brandenburg State Office for Environment. p. 20. ISBN 978-3-00-059256-0.

- ^ Expedition solves Aquatic Warbler mystery, Birdlife International (2007). Retrieved 2012

- ^ Leisler, B. & Wink, Michael (2000): "Frequencies of multiple paternity in three Acrocephalus species (Aves: Sylviidae) with different mating systems (A. palustris, A. arundinaceus, A. paludicola)". Ethology, Ecology & Evolution 12: 237-249.

- ^ Jobling, James A (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 30, 290. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- ^ "List of conservation projects" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-12-10. Retrieved 2012-11-22.

- ^ "Protecting aquatic warbler: farming in wet meadows and fen mires by Baltic Environmental Forum Lithuania - Issuu". issuu.com. 3 October 2017.

- ^ "Home". Nine voices.

- ^ "Translocation of the Aquatic Warbler" (PDF). meldine.lt.

- ^ "New habitat for Europe's rarest song bird". EASME - European Commission. 2019-02-15. Archived from the original on 2019-05-31. Retrieved 2019-09-04.

- ^ Grinienė, Rita (2019-06-27). "First ever Aquatic Warbler translocation confirmed to be effective". meldine.lt. Archived from the original on 2019-07-07. Retrieved 2019-09-04.

- ^ Grinienė, Rita (2019-07-15). "50 aquatic warbler nestlings are successfully released into the wild". meldine.lt. Retrieved 2019-09-04.

External links

[edit]- ARKive - images and movies of the aquatic warbler (Acrocephalus paludicola)

- BirdLife International The Aquatic Warbler Conservation Team

- Conserving Aquatic Warbler in Poland and Germany an EU LIFE NATURE project

- Baltic Aquatic Warbler an EU LIFE NATURE project

- Magni Ducatus Acrola an EU LIFE NATURE project

- CMS Aquatic Warbler Memorandum of Understanding

- Ageing and sexing (PDF; 1.3 MB) by Javier Blasco-Zumeta & Gerd-Michael Heinze