Athletics in epic poetry

In epic poetry, athletics are used as literary tools to accentuate the themes of the epic, to advance the plot of the epic, and to provide a general historical context to the epic. Epic poetry emphasizes the cultural values and traditions of the time in long narratives about heroes and gods.[1] The word "athletic" is derived from the Greek word athlos, which means a contest for a prize.[2] Athletics appear in some of the most famous examples of Greek and Roman epic poetry including Homer's Iliad and Odyssey, and Virgil's Aeneid.

Greek epic poetry

[edit]Iliad

[edit]Achilles and Hector

[edit]In Iliad 22, Achilles is seeking to avenge the death of Patroclus by killing Hector, Patroclus' killer.[3] After being distracted by Apollo, Achilles:

spoke, and stalked away against the city, with high thoughts in mind, and in tearing speed, like a racehorse with his chariot who runs lightly as he pulls the chariot over the flat land. Such was the action of Achilleus in feet and quick knees (Iliad 22.21-24, Richmond Lattimore, Translator).

Priam, the King of Troy, was the first to spot the rapidly approaching Achilles.[4] Calling out to Hector, Priam warned Hector about the approaching Achilles and pleaded with Hector to return into the city.[5] Despite Priam's pleading, Hector stayed outside the walls of Troy ready to fight to the death against Achilles.[6] However, moments before Achilles reached Hector, Hector was overtaken with fear and decided to flee.[7][8] Hector and Achilles:

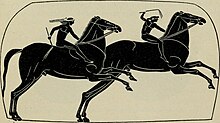

ran beside these, one escaping, the other after him. It was a great man who fled, but far better he who pursued him rapidly, since here was no festal beast, no ox-hide they strove for, for these are prizes that are given men for their running. No, they ran for the life of Hektor, breaker of horses. As when about the turnposts racing single-foot horses run at full speed, when a great prize is laid up for their winning, a tripod or a woman, in games for a man’s funeral, so these two swept whirling about the city of Priam in the speed of their feet, while all the gods were looking upon them (Iliad 22.157-66, Richmond Lattimore, Translator).

The funeral games for Patroclus

[edit]Synopsis

[edit]In Iliad 23, Achilles organizes a series of athletic competitions to honor Patroclus, the fallen Achaean hero. The games also served as a break-point in the Trojan war following the crucial return of Achilles to the battlefield and the death of Hector. Following the burial of Patroclus, Achilles declares to the assembled Achaean Army that funeral games will be held in honor of Patroclus. Achilles then set fourth a number of his cherished possessions to serve as prizes for the ensuing athletic competitions .[9]

In the first event, Diomedes won a very competitive chariot race with Athena's help.[10] Following the chariot race, Epeios and Euryalos fought in a boxing match. Epeios ended the fight with one punch.[11] Next, Odysseus and Telamonian Aias competed in a wrestling competition. Fearing injury, Achilles ended the wrestling competition in a tie.[12] In the forth event, an Athena aided Odysseus won a foot race over Aias and Antilochos.[13] After the footrace, Telamonian Aias and Diomedes faced off in duel with spears. Once again fearing injury, Achilles ended the fight early and gave Diomedes first because Diomedes would have ultimately won.[14] In the sixth event, Polypoites won a discus throwing competition by launching a discus well beyond the marks set by the other participants.[15] An archery competition between Teukros and Meriones ensued after the discus throwing competition. Meriones won the archery competition after praying for Apollo's help.[16] For the final competition, Agamemnon and Meriones stepped forth to compete in a spear-throwing competition; however, Achilles declared Agamemnon the victor before the competition could take place.[17]

Odyssey

[edit]The Phaeacian Games

[edit]In Odyssey 8, Odysseus lands on the island of the Phaeacians. During Odysseus' time there, the Phaeacians stage a series of athletic contests for Odysseus so that he could spread stories about the Phaeacians' athletic prowess. First, the Phaeacians competed in a foot race. Following the foot race, the Phaeacians battled each other in a fierce wrestling competition. After wrestling, the Phaeacians held jumping and boxing contests. The fifth and final event was the discus throw. After the discus competition, Odysseus is invited to show his athletic skills, but he declines the offer. After declining the offer, one Phaeacian, Euryalos, joked that Odysseus did not have the skills to compete in an athletic competition. This infuriated Odysseus. The angered Odysseus then grabbed a discus much larger and heavier than the ones used by the Phaeacians, and he swung back and released the discus. The discus landed well clear of the Phaeacians' earlier marks. Odysseus then challenged the Phaeacians to other athletic competitions, which they declined.[18]

Odysseus and the Suitors

[edit]

After evading the suitors' advances for many years in hopes that Odysseus might return, Penelope finally relented to the suitors' advances for her hand in marriage and set forth a challenge to determine which suitor she would marry. To obtain her hand in marriage, the suitor must string the bow of Odysseus and shoot an iron arrow clean through twelve axes. Telemachos, son of Odysseus and Penelope, stepped forth to attempt the athletic feat first in hopes of protecting his family's house. Telemachos tried three times to string the bow of Odysseus but failed each time. Odysseus, disguised as a beggar, stopped Telemachos from trying a fourth time. After Telemachos, suitor after suitor attempted the challenge, but all their attempts ended in failure. Odysseus, still disguised as an unknown beggar, then asked for a chance to shoot the bow. The suitors mockingly refused the disguised Odysseus' request, but Telemachos stepped in to give the beggar, Odysseus, a chance. Odysseus stepped up to line and took his time examining his bow. He then proceeded to string the bow with much ease, to the dismay of the suitors. Odysseus then released the string and let the arrow fly. It soared clean through all twelve axes. Odysseus then revealed himself, to much the shock of the suitors.[19]

Argonautica

[edit]The Berbrykians

[edit]In Argonautica 2, the Argonauts landed on a stretch of land inhabited by a pretentious group of people called the Berbrykians. Ignoring the traditional welcoming practices, Amykos, the king of the Berbrykians, stepped forward immediately to inform the Argonauts of the Berbrykians' ordinance that no foreigners may leave until one member of the group competes in boxing match against him. Irritated, Polydeukes accepted Amykos' challenge quickly. The Argonauts and the Berbrykians gathered around as the two fighters prepared to fight. After strapping on the knuckle wraps, the fight began with great intensity. Amykos came out throwing punches left and right, but Polydeukes dodged Amykos' early onslaught with much ease. The two fighters traded punches back and forth until Polydeukes delivered a counter punch that sent Amykos to ground.[20]

Other examples

[edit]Aethiopis and Little Iliad

[edit]The Aethiopis and the Little Iliad are lost epics of ancient Greek literature that follows the events of Iliad.[21] In the few surviving fragments of the epic, the poem describes Agamemnon arriving to the battlefield in Troy to fight against the Achaeans. Agamemnon, wearing armor of Hephaestus, killed Antilochus, son of Nestor, which caused Achilles to become enraged. In his rage, Achilles kills Agamemnon and proceeds into the gates of Troy to inflict more casualties on Trojan army. As he entered the gates of Troy, Achilles was fatally struck with an arrow shot by Paris, assisted by Apollo. Odysseus and Ajax retrieved the body of Achilles. The Achaeans then hold burial rights for both Antilochus and Achilles. The burial of Achilles is attended by the goddess mother of Achilles, Thetis, along with her sisters and the muses. Following the funerals, the Achaeans honored Achilles' death with ceremonial games. In the games, Ajax and Odysseus competed for the title of greatest hero and for the grand prize of Achilles of precious armor.[22]

The Little Iliad follows the events of the Aethiopis. The epic starts in middle of the funeral games for Achilles with Odysseus and Ajax competing for the armor of Achilles and the title of the greatest hero. After competing back and forth for some time, Odysseus, with the help of Athena, claimed victory over Ajax. Following his defeat, Ajax became mad and committed suicide.[23]

The Battle of Frogs and Mice

[edit]As The Battle of Frogs and Mice begins, Puff-jaw, a frog, inquisitively asks the identity of the stranger, a mouse, near the edge of the water. The mouse replies that he is Crumb-snatcher, and he proceeds to boast about the abilities of mice. Becoming annoyed with Crumb-snatcher's boasting, Puff-jaw invites the mouse to climb onto his back so that the mouse could experience deeper water. The mouse agrees, and the two swim out into the water. However, as they get into deeper water, a snake appears. In fear, Puff-jaw dives below the water leaving Crumb-snatcher to die. In his final words, Crumber-snatcher calls out to Puff-jaw yelling, "On land you would not have been the better man, boxing, or wrestling, or running; but now you have tricked me and cast me in the water."[24]

Homeric Hymns- III. To Apollo

[edit]Many are your temples and wooded groves, and all peaks and towering bluffs of lofty mountains and rivers flowing to the sea are dear to you, Phoebus, yet in Delos do you most delight your heart; for there the long robed Ionians gather in your honour with their children and shy wives: mindful, they delight you with boxing and dancing and song, so often as they hold their gathering. (Lines 140-164) [25]

Hesiod's The Shield of Heracles

[edit]Preparing for battle, Heracles donned his armor and pick up his glorious shield. The shield was a gift from Anthea before he set off to complete his labours. Crafted and forged by the god Hephaestus with ivory and gold, the Shield of Heracles stood undefeated in battle. The shield bore images of men boxing and wrestling as hunters chased hares accompanied by their loyal dogs. Horsemen were set waiting to contend for prizes. Stuck in an unending race, charioteers urged their horses onto the finish, but the prize of gold forever lay out of reach.[26]

Hesiod's Theogony

[edit]According to Hesiod's Theogony, the goddess Hecate:

"greatly aids and advances: she sits by worshipful kings in judgement, and in the assembly whom she will is distinguished among the people. And when men arm themselves for the battle that destroys men, then the goddess is at hand to give victory and grant glory readily to whom she will. Good is she also when men contend at the games, for there too the goddess is with them and profits them: and he who by might and strength gets the victory wins the rich prize easily with joy, and brings glory to his parents."[27]

Hesiod's Work and Days

[edit]Hesiod wrote:

"Then I crossed over to Chalcis, to the games of wise Amphidamas where the sons of the great-hearted hero proclaimed and appointed prizes. And there I boast that I gained the victory with a song and carried off an handled tripod which I dedicated to the Muses of Helicon, in the place where they first set me in the way of clear song." (Work and Days Lines 646-663)[28]

Roman epic poetry

[edit]Aeneid

[edit]The funeral games for Anchises

[edit]In Aeneid 5, Aeneas organizes funeral games to commemorate the one-year anniversary of Anchises, the father of Aeneas.[29] Aeneas invited the best of the Trojans and the Sicilians to complete for prizes and wreaths. A trumpet blew to signal the start of the games.[30] For the first event, fans lined the beach to watch four crews of men race ships in the open water.[31] After praying to the gods of the sea, Cloanthus raced to the finish taking first place. Next, Aeneas and the large number of spectators gathered to watch a group of Sicilians and Trojans compete in a footrace that was eventually won by Euryalus.[32] Following the footrace, Dares and Entellus faced off in a heated boxing match. The match ended with Aeneas stepping to stop the fight and declaring Entellus the winner.[33] After boxing, the Sicilian King, Acestes, fired a magnificent arrow from his bow to win the archery competition.[34] In the final event, male youths competed in an equestrian military exercise.[35][36]

Metamorphoses

[edit]Apollo and the Python

[edit]

In Ovid's Metamorphoses 1, Apollo slays Python, the enormous serpent-like creature, with his bow and arrow. To honor Apollo's great accomplishment, the Pythian games were created to celebrate the death of Python.[37] At the Pythian games, the youth competed in boxing, footraces, and chariot races. The winners of these events received oaken garland as their prize because laurel did not exist yet.[38]

The Pythian Games were ceremonial games held every four years at a site near Delphi to honor Apollo's slaying of the serpent.[39] The games were part of the Panhellenic Games and were held from about 586 B.C. to 394 A.D.[39][40] The Pythian Games occurred at the third year of each Olympiad and was of second importance to the Olympics.[41] The Pythian Games differed from the Olympic Games in that it also held musical competitions as part of the festival.[42] The athletic competition consisted on four types of athletics: footraces, pentathlon, combat sports, and equestrian events.[43] Starting in 582 B.C. The victors of these competitions received laurels wreaths as prizes for victory.[44]

Acheloüs and Hercules

[edit]

In Ovid's Metamorphoses 9, Achelous, a river god, tells Theseus the story of how he lost his horns. There was a very beautiful woman named Deianira, who had many suitors. The many suitors of Deianira gathered in the palace of Deianira's father in hopes of marrying her. However, once the other suitors realized that Acheloüs, a god, and Heracules, the son of Jupiter, wanted to marry Deianira, the other suitors withdrew from the competition. This left only Acheloüs and Hercules as the only two suitors. Each spoke to Deianira's father proclaiming they should be the one to have her hand in marriage. After Acheloüs concluded his speech, Hercules charged at Acheloüs and the two began to wrestle. At the first, the two grappled pretty evenly; however, after many attempts, Hercules finally started to get the better of Acheloüs. Hercules was locked onto Acheloüs' back and put Acheloüs into a strangle hold. Feeling impending defeat in this human form, Acheloüs transformed into a snake. Laughing, Hercules easily began to choke out the snake-formed Acheloüs. Hercules had defeated a much more fierce snake while just a baby, so Acheloüs was no match to Hercules in snake-form. Finally, Acheloüs decided to transform into a bull. Hercules grabbed the bull by the neck and shoved Acheloüs' head deep into the dirt. Then, Hercules grabbed Acheloüs' horn tore it from his head. Hercules then took Deianira as his wife.[45]

Atalanta and Hippomenes

[edit]

In Ovid's Metamorphoses 10, Venus tells Adonis the story of Atalanta and Hippomenes.[46] Known for her beauty and running ability, Atalanta consulted a god to ask about marriage.[47] The god responded by telling Atalanta that a husband is not for you, and the god also prophesied that Atalanta would not take this warring to heart.[47] Worried by the god's message, Atalanta set forth a challenge for all her suitors. To win her hand in marriage, the suitor must beat her in a footrace. However, if the suitor lost, then he would be killed.[48] Hippomenes watched from the stands as suitors met their grim fate, and he wondered why on a man would take such a risk just for a woman.[49] However, Hippomenes caught a glimpse of Atalanta naked and was overcome by her beauty.[50] Then, Hippomenes decided to challenge Atalanta to a footrace in hopes that he would be able to marry her. Before the race began, Hippomenes prayed to Venus for help. Venus gave Hippomenes three golden apples, and she told him to use apples to distract Atalanta during the race.[51] The race began with the two running side by side, but as race wore on, Atalanta started to pull ahead of the tired of Hippomenes. Then, Hippomenes launched the first golden apple given to him by Venus. Atalanta became distracted and retrieved the golden apple allowing Hippomenes to take the lead.[52] However, Atalanta quickly recovered and took the lead again. Hippomenes threw the second apple. Atalanta, once again, retrieved the golden apple and easily retook the lead.[53] Finally, Hippomenes threw the final apple with all his strength. As Atalanta retrieved the third golden apple, Hippomenes crossed the finish line to win Atalanta's hand in marriage.[54]

Peleus and Thetis

[edit]

In Metamorphoses 11, Jupiter learns of the prophecy about a son born from Thetis, a sea goddess. The prophecy declared that the son of Thetis would achieve greater things than his father and would be considered greater than his father, which deeply frighten Jupiter. After the hearing the prophecy, Jupiter decided it would be best to have Peleus, Jupiter's mortal grandson, to take Thetis as a wife. Thus Peleus set out to find Thetis as Jupiter had suggested. Once Peleus found Thetis, Peleus made his advances towards her, but Thetis rejected Peleus. The rejected Peleus then lunged at Thetis and grabbed her around the neck. The two wrestled back and forth until Thetis changed into a bird. However, Peleus would not let go, so Thetis transformed into a tree. This transformation still did not work, so Thetis transformed into a tiger causing the scared Peleus to let go. After Thetis escaped, the dejected Peleus decided to consult the other sea gods for help. The sea gods told Peleus that he must bind Thetis up with chains while she slept and to hold her close until she changed back into her human form. Once Thetis fell asleep, Peleus approached and bound Thetis. Thetis attempted to free herself from Peleus grips by changing into many different forms, but nothing worked. Thetis finally relented and the baby Achilles was conceived.[55]

Themes

[edit]Kleos and Timê

[edit]Kleos (glory) and Timê (renown) are recurrent themes throughout ancient epic. As the heroes progress through the epics, heroes work to achieve honor and glory through their actions, but also through their material possessions.[56][57] Athletic competitions served as a way to gain glory for the characters in epic. In a historical context, athletes in the ancient Olympics were rewarded with highly valued prizes for their accomplishments.[58] Their legacies still live on today through statues and monuments constructed in their honor hundreds of years ago.[59] The funeral games in the Iliad and the Aeneid serve as two examples where athletes win material prizes, but also gain the glory and honor associated with the retelling of the story.[60][61]

Historical context

[edit]

Sports competitions are believed to have taken place over 3,000 years ago at Olympia in Greece; hence, the name the "Olympics". The first written account of the Games dates back to 776 BC. The exact origin and reasons behind the multi-day event is believed to be a result of ensuring peace between the city-states in the Hellenic world. These original games at Olympia gave rise to the Panhellenic Games. The Panhellenic games consisted of four individual "Olympic-Style" competitions held throughout the ancient Greek world. The served as a way to bring ancient Greece together.[40]

Athletes trained to compete in the games starting at very young age. Located in every Greek city, gymnasiums and palaestras provided young Greek males with both a place to learn and to train. However, only the best the athletes were selected to compete in the Olympic games. Once selected, an athlete had to take an oath to compete in an honorable way and to abide by the rules.[40] The athletes competed in a variety of different athletic events such as chariot racing, boxing, and wrestling.[62] An athlete could expect a life of luxury should he win an event. In 600 B.C., an Athenian athlete would receive a large cash prize for victory. In later times victors would receive meals for the rest of their lives. In addition, great athletes could expect to be immortalized for all time in much the same way as the heroes in ancient epic.[58] Statues and tombs celebrating the athletes in ancient Greece can still be seen today.[40]

Further reading

[edit]- Christesen, Paul; Kyle, Donald (2013). Blackwell Companions to the Ancient World : Companion to Sport and Spectacle in Greek and Roman Antiquity. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 9781118610862.

References

[edit]- ^ Kip, Wheeler. "What is an Epic?" (PDF). Dr. Wheeler's Homepage at Carson-Newman University. Retrieved April 7, 2016.

- ^ Christesen, Paul; Kyle, Donald (2013). Blackwell Companions to the Ancient World : Companion to Sport and Spectacle in Greek and Roman Antiquity. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 2. ISBN 9781118610862.

- ^ Homer. The Iliad, Richmond Lattimore, translator. Chicago University of Chicago Press (2011). 21.224-26.

- ^ Homer. The Iliad, Richmond Lattimore, translator. Chicago University of Chicago Press (2011). 22.25.

- ^ Homer. The Iliad, Richmond Lattimore, translator. Chicago University of Chicago Press (2011). 22.37-76.

- ^ Homer. The Iliad, Richmond Lattimore, translator. Chicago University of Chicago Press (2011). 22.99-130.

- ^ Homer. The Iliad, Richmond Lattimore, translator. Chicago University of Chicago Press (2011). 22.136-38.

- ^ Christesen, Paul; Kyle, Donald (2013). Blackwell Companions to the Ancient World : Companion to Sport and Spectacle in Greek and Roman Antiquity. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 63. ISBN 9781118610862.

- ^ Homer. The Iliad, Richmond Lattimore, translator. Chicago: University of Chicago Press (2011). 23.249-259.

- ^ Homer. The Iliad, Richmond Lattimore, translator. Chicago: University of Chicago Press (2011). 23.257-650.

- ^ Homer. The Iliad, Richmond Lattimore, translator. Chicago: University of Chicago Press (2011). 23.651-699.

- ^ Homer. The Iliad, Richmond Lattimore, translator. Chicago: University of Chicago Press (2011). 23.700-739.

- ^ Homer. The Iliad, Richmond Lattimore, translator. Chicago: University of Chicago Press (2011). 23.740-796

- ^ Homer. The Iliad, Richmond Lattimore, translator. Chicago: University of Chicago Press (2011). 23.797-825.

- ^ Homer. The Iliad, Richmond Lattimore, translator. Chicago: University of Chicago Press (2011). 23.826-849.

- ^ Homer. The Iliad, Richmond Lattimore, translator. Chicago: University of Chicago Press (2011). 23.850-883.

- ^ Homer. The Iliad, Richmond Lattimore, translator. Chicago: University of Chicago Press (2011). 23.884-97.

- ^ Homer; Translated By: Richard Lattimore (2009). The Odyssey of Homer. New York, NY: Happer Collins e-books. pp. Book 8 (p.123–127). ASIN B002TIOYT4.

- ^ Homer; Translated By: Richard Lattimore (2009). The Odyssey of Homer. New York, NY: Happer Collins e-books. pp. Book 21 (p.308–320). ASIN B002TIOYT4.

- ^ Apollonios Rhodios (2007). The Argonautika. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. pp. 79–81. ISBN 9780520253933.

- ^ "Classical E-Text: GREEK EPIC CYCLE". www.theoi.com. Retrieved 2016-05-08.

- ^ "THE AETHIOPIS (fragments)". The Project Gutenberg. Editor: Evelyn-White, Hugh G.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "Little Iliad". Project Gutenberg. Edited By: Evelyn-White, Hugh G. July 5, 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Evelyn-White, Hugh (ed.). "The Battle of Frogs and Mice". Project Gutenberg.

- ^ "TO DELIAN APOLLO". PROJECT GUTENBERG. Edited By: Evelyn-White, Hugh G. July 5, 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Hesiod (2008). Evelyn-White, Hugh (ed.). The Shield of Hercules. Project Gutenberg.

- ^ Hesiod (1987). Hesiod's Theogony. Translated By: Caldwell, Richard S. Newburyport, MA: Focus Publishing. pp. Lines 400–452. ISBN 978-0-941051-00-2.

- ^ Hesiod (July 5, 2008). "WORKS AND DAYS". Project Gutenberg. Translated By: Evelyn-White, Hugh G.

- ^ Virgil. Aeneid, Frederick Ahl, translator. Oxford University Press (2007). 5.47-70.

- ^ Virgil. Aeneid, Frederick Ahl, translator. Oxford University Press (2007). 5.113.

- ^ Virgil. Aeneid, Frederick Ahl, translator. Oxford University Press (2007). 5.107-285.

- ^ Virgil. Aeneid, Frederick Ahl, translator. Oxford University Press (2007). 5.286-361.

- ^ Virgil. Aeneid, Frederick Ahl, translator. Oxford University Press (2007). 5.363-484.

- ^ Virgil. Aeneid, Frederick Ahl, translator. Oxford University Press (2007). 5.485-544.

- ^ Virgil. Aeneid, Frederick Ahl, translator. Oxford University Press (2007). 5.585-603.

- ^ "The Flaming Arrow of Classical Education: Funeral Games in the Aeneid as Symbol and Hope". Circe Institute. Archived from the original on 2016-04-04. Retrieved 2016-05-08.

- ^ Ovid. Metamorphoses, Charles Martin, translator. W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. (2010). 1.607-21.

- ^ Ovid. Metamorphoses, Henry Riley, translator. George Bell & Sons (1893). 1.443-54.

- ^ a b Ovid. Metamorphoses, Charles Martin, translator. W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. (2010). p. 20.

- ^ a b c d The Olympic Museum Educational and Cultural Services (2013). "The Olympic Games in Antiquity" (PDF). The Olympics. The Olympic Museum. Retrieved April 7, 2016.

- ^ Christesen, Paul; Kyle, Donald (2013). Blackwell Companions to the Ancient World : Companion to Sport and Spectacle in Greek and Roman Antiquity. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 177. ISBN 9781118610862.

- ^ Christesen, Paul; Kyle, Donald (2013). Blackwell Companions to the Ancient World : Companion to Sport and Spectacle in Greek and Roman Antiquity. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 179–180. ISBN 9781118610862.

- ^ Christesen, Paul; Kyle, Donald (2013). Blackwell Companions to the Ancient World : Companion to Sport and Spectacle in Greek and Roman Antiquity. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 179. ISBN 9781118610862.

- ^ Christesen, Paul; Kyle, Donald (2013). Blackwell Companions to the Ancient World : Companion to Sport and Spectacle in Greek and Roman Antiquity. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 180. ISBN 9781118610862.

- ^ Ovid. Metamorphoses, Charles Martin, translator. W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. (2010). 9.1-148.

- ^ Ovid. Metamorphoses, Charles Martin, translator. W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. (2010). 10.665-66.

- ^ a b Ovid. Metamorphoses, Charles Martin, translator. W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. (2010). 10.670-73.

- ^ Ovid. Metamorphoses, Charles Martin, translator. W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. (2010). 10.674-79.

- ^ Ovid. Metamorphoses, Charles Martin, translator. W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. (2010). 10.680-84.

- ^ Ovid. Metamorphoses, Charles Martin, translator. W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. (2010). 10.690-750.

- ^ Ovid. Metamorphoses, Charles Martin, translator. W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. (2010). 10.751-63.

- ^ Ovid. Metamorphoses, Charles Martin, translator. W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. (2010). 10.764-82.

- ^ Ovid. Metamorphoses, Charles Martin, translator. W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. (2010). 10.785-86.

- ^ Ovid. Metamorphoses, Charles Martin, translator. W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. (2010). 10.788-94.

- ^ Ovid. Metamorphoses, Charles Martin, translator. W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. (2010). 11.313-77.

- ^ Scott, William (January 1998). "The Etiquette of Games in Iliad 23". Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies. 38 (3): 213–227. ISSN 0017-3916. Retrieved April 7, 2016.

- ^ Buzby, Russell (2007). "Portrayals of Heroism –Achilles, Agamemnon and Iphigenia" (PDF). Cross Sections: The Bruce Hall Academic Journal.

- ^ a b "The Athletes | The Real Story of the Ancient Olympic Games - Penn Museum". www.penn.museum. Retrieved 2016-04-12.

- ^ The Olympic Museum Educational and Cultural Services (2013). "The Olympic Games in Antiquity" (PDF). The Olympics. The Olympic Museum. Retrieved April 7, 2016.

- ^ Homer. The Iliad. pp. Book 23.

- ^ Vergil; Translated By: Ruden, Sarah (2008). The Aeneid. New Haven, CT: Yale University. pp. 91–116. ISBN 9780300151411.

- ^ "Ancient Sports". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2016-04-12.