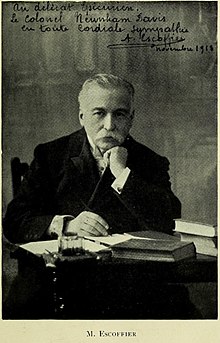

Auguste Escoffier

Auguste Escoffier | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Georges Auguste Escoffier 28 October 1846 Villeneuve-Loubet, France |

| Died | 12 February 1935 (aged 88) Monte Carlo, Monaco |

Georges Auguste Escoffier (French: [ʒɔʁʒ ɔɡyst ɛskɔfje]; 28 October 1846 – 12 February 1935) was a French chef, restauranteur and culinary writer who popularized and updated traditional French cooking methods. He is a legendary figure among chefs and gourmets, and was one of the most important leaders in the development of modern French cuisine. Much of Escoffier's technique was based on that of Marie-Antoine Carême, one of the codifiers of French haute cuisine, but Escoffier's achievement was to simplify and modernize Carême's elaborate and ornate style. In particular, he codified the recipes for the five mother sauces. Referred to by the French press as roi des cuisiniers et cuisinier des rois ("king of chefs and chef of kings"[1]—though this had also been previously said of Carême), Escoffier was France's preeminent chef in the early part of the 20th century.

Alongside the recipes he recorded and invented, another of Escoffier's contributions to cooking was to elevate it to the status of a respected profession by introducing organized discipline to his kitchens.

Escoffier published Le Guide Culinaire, which is still used as a major reference work, both in the form of a cookbook and a textbook on cooking. Escoffier's recipes, techniques and approaches to kitchen management remain highly influential today, and have been adopted by chefs and restaurants not only in France, but also throughout the world.[2]

Early life

Escoffier was born in the village Villeneuve-Loubet, today in Alpes-Maritimes, near Nice. The house where he was born is now the Musée de l'Art Culinaire, run by the Foundation Auguste Escoffier. At the age of thirteen, despite showing early promise as an artist, he started an apprenticeship at his uncle's restaurant, Le Restaurant Français, in Nice. In 1865, he moved to Le Petit Moulin Rouge restaurant in Paris. He stayed there until the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870, when he became an army chef. His army experience led him to study the technique of canning food. Some time before 1878, he opened his own restaurant, Le Faisan d'Or (The Golden Pheasant), in Cannes.

In 1880, he married Delphine Daphis.

Escoffier, César Ritz and the Savoy

In 1884, the couple moved to Monte Carlo, where Escoffier was employed by César Ritz, manager of the new Grand Hotel, to take control of the kitchens. At that time, the French Riviera was a winter resort: during the summers, Escoffier ran the kitchens of the Grand Hôtel National in Lucerne, also managed by Ritz.[3][4]

In 1890, Ritz and Escoffier accepted an invitation from Richard D'Oyly Carte to transfer to his new Savoy Hotel in London, together with the third member of their team, the maître d'hôtel, Louis Echenard.[3] Ritz put together what he described as "a little army of hotel men for the conquest of London", and Escoffier recruited French cooks and reorganised the kitchens. The Savoy under Ritz and his partners was an immediate success, attracting a distinguished and moneyed clientele, headed by the Prince of Wales. Gregor von Görög, chef to the royal family, was an enthusiast of Escoffier's zealous organization. Aristocratic women, hitherto unaccustomed to dining in public, were now "seen in full regalia in the Savoy dining and supper rooms".[3]

Escoffier created many famous dishes at the Savoy. In 1893, he invented the pêche Melba in honour of the Australian singer Nellie Melba, and in 1897, Melba toast. Other Escoffier creations, famous in their time, were the bombe Néro (a flaming ice), fraises à la Sarah Bernhardt (strawberries with pineapple and Curaçao sorbet), baisers de Vierge (meringue with vanilla cream and crystallised white rose and violet petals) and suprêmes de volailles Jeannette (jellied chicken breasts with foie gras).[5][6] He also created salad Réjane, after Gabrielle Réjane, and (although this is disputed) tournedos Rossini.[7]

On 8 March 1898, Ritz, Echenard and Escoffier were dismissed from the Savoy "for ... gross negligence and breaches of duty and mismanagement". Disturbances in the Savoy kitchens on that day reached the newspapers, with headlines such as "A Kitchen Revolt at The Savoy".[7]The Star reported: "Three managers have been dismissed and 16 fiery French and Swiss cooks (some of them took their long knives and placed themselves in a position of defiance) have been bundled out by the aid of a strong force of Metropolitan police."[8] The real details of the dispute did not emerge at first. Ritz and his colleagues even prepared to sue for wrongful dismissal. Eventually, they settled the case privately: on 3 January 1900, Ritz, Echenard and Escoffier "made signed confessions, admitting to actual criminal acts including fraud" but their confessions "were never used or made public".[9] For example, wines and spirits to the value of £6,400 had been diverted in the first six months of 1897. Escoffier additionally confessed to taking gifts or bribes from the Savoy’s suppliers worth up to 5% of the resulting purchases.[10] Escoffier accepted an obligation to repay £8,000, but was allowed to settle his debt for £500. Ritz and Echenard paid a much higher sum.[11]

The Ritz and the Carlton

By that time, however, Ritz and his colleagues were on the way to commercial independence, having established the Ritz Hotel Development Company, for which Escoffier set up the kitchens and recruited the chefs, first at the Paris Ritz (1898), and then at the new Carlton Hotel in London (1899), which soon drew much of the high-society clientele away from the Savoy.[3] In addition to the haute cuisine offered at luncheon and dinner, tea at the Ritz became a fashionable institution in Paris, and later in London, though it caused Escoffier real distress: "How can one eat jam, cakes and pastries, and enjoy a dinner – the king of meals – an hour or two later? How can one appreciate the food, the cooking or the wines?"[12]

In 1913, Escoffier met Kaiser Wilhelm II on board the SS Imperator, one of the largest ocean liners of the Hamburg-Amerika Line. The culinary experience on board the Imperator was overseen by Ritz-Carlton,[clarification needed] and the restaurant itself was a reproduction of Escoffier's Carlton Restaurant in London. Escoffier was charged with supervising the kitchens on board the Imperator during the Kaiser's visit to France. One hundred and forty-six German dignitaries were served a large multi-course luncheon, followed that evening by a monumental dinner that included the Kaiser's favourite strawberry pudding, named fraises Imperator by Escoffier for the occasion. The Kaiser was so impressed that he insisted on meeting Escoffier after breakfast the next day, where, as legend has it, he told Escoffier, "I am the Emperor of Germany, but you are the Emperor of Chefs." This was quoted frequently in the press, further establishing Escoffier's reputation as France's pre-eminent chef.[13]

Ritz gradually moved into retirement after opening The Ritz London Hotel in 1906, leaving Escoffier as the figurehead of the Carlton until his own retirement in 1920. He continued to run the kitchens through the First World War, during which time his younger son was killed in active service.[3] Recalling these years, The Times said, "Colour meant so much to Escoffier, and a memory arises of a feast at the Carlton for which the table decorations were white and pink roses, with silvery leaves – the background for a dinner all white and pink, Borscht striking the deepest note, Filets de poulet à la Paprika coming next, and the Agneau de lait forming the high note."[14]

In 1928, he helped create the World Association of Chefs Societies and became its first president.

Death

Escoffier died on 12 February 1935, at the age of 88, in Monte Carlo,a few days after the death of his wife.

Publications

- Le Traité sur L'art de Travailler les Fleurs en Cire (Treatise on the Art of Working with Wax Flowers) (1886)

- Le Guide Culinaire (1903)

- Les Fleurs en Cire (new edition, 1910)

- Le Carnet d'Epicure (A Gourmet's Notebook), a monthly magazine published from 1911 to 1914

- Le Livre des Menus (Recipe Book) (1912)

- L'Aide-memoire Culinaire (1919)

- Le Riz (Rice) (1927)

- La Morue (Cod) (1929)

- Ma Cuisine (1934)

- 2000 French Recipes (1965, translated into English by Marion Howells) ISBN 1-85051-694-4

- Memories of My Life (1996, from his own life souvenirs,[clarification needed] published by his grandson in 1985 and translated into English by L. Escoffier, his great-granddaughter-in-law), ISBN 0-471-28803-9

- Les Tresors Culinaires de la France (2002, collected by L. Escoffier from the original Carnet d'Epicure)

References

- ^ Claiborne, Craig & Franey, Pierre. Classic French Cooking

- ^ Gillespie, Cailein & Cousins, John A. European Gastronomy into the 21st Century, pp. 174–175 ISBN 0-7506-5267-5

- ^ a b c d e Ashburner, F."Escoffier, Georges Auguste (1846–1935)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edition, May 2006, accessed 17 September 2009

- ^ Allen, Brigid. "Ritz, César Jean (1850–1918)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, September 2004; online edition, May 2006, accessed 18 September 2009

- ^ The Times, 13 February 1935, p. 14; and 16 February 1935, p. 17

- ^ Escoffier, Auguste, A Guide to Modern Cookery, p. 405 (English translation of Le Guide Culinaire, by H. L. Cracknell and R. J. Kaufmann) ISBN 0-471-29016-5

- ^ a b Augustin, Andreas; Williamson, Andrew. "The Most Famous Hotels in the World: The Savoy", 4Hoteliers, 30 October 2006, accessed 4 September 2013

- ^ The Star (8 March 1898) as quoted at "The Most Famous Hotels in the World: The Savoy", famoushotels.org

- ^ Paul Levy, "Should Gordon Ramsay behave more like Escoffier?" in The Guardian: Word of Mouth Blog (7 March 2009)

- ^ Paul Levy, "The master chef who cooked the books" in The Daily Telegraph (9 June 2012)

- ^ "Kitchen Revolt at The Savoy: 16 fiery cooks took their long knives" at famoushotels.org

- ^ The Times, 13 February 1935, p. 14

- ^ James, Kenneth. Escoffier: The King of Chefs., 2006. ISBN 1-85285-526-6

- ^ The Times, 16 February 1935, p. 17

Further reading

- Kelby, N. M. White Truffles in Winter (2011) ISBN 978-0-393-07999-9

- Chastonay, Adalbert. Cesar Ritz: Life and Work (1997) ISBN 3-907816-60-9.

- Escoffier, Georges-Auguste. Memories of My Life (1997) ISBN 0-442-02396-0.

- Shaw, Timothy. The World of Escoffier. (1994) ISBN 0-86565-956-7.

- Patrick Rambourg, Histoire de la cuisine et de la gastronomie françaises, Paris, Ed. Perrin (coll. tempus n° 359), 2010, 381 pages. ISBN 978-2-262-03318-7

External links

- Works by or about Auguste Escoffier at the Internet Archive

- Works by Auguste Escoffier at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)