Bandenbekämpfung

Bandenbekämpfung is a German-language term that means "bandit fighting" or "combating of bandits". In the context of German military history, Bandenbekämpfung was an operational doctrine that was part of countering resistance or insurrection in the rear area during wars. Another more common understanding of Bandenbekämpfung is anti-partisan warfare. The doctrine of "bandit-fighting" provided a rationale to target and murder any number of groups, from armed guerrillas to the civilian population, as "bandits" or "members of gangs". As applied by the German Empire and then Nazi Germany, it became instrumental in the genocidal programs implemented by the two regimes, including the Holocaust.

Origins

According to historian and television documentary producer, Christopher Hale, there are indications that the term Bandenbekämpfung may go back as far as the Thirty Years' War.[1] Under the German Empire established by Bismarck in 1871 after the Franco-Prussian War—formed as a union of twenty-five German states under the Hohenzollern king of Prussia—Prussian militarism flourished; martial traditions that included the military doctrine of Antoine-Henri Jomini's 1837 treatise, Summary of the Art of War were put into effect.[2] Some of the theories laid out by Jomini contained instructions for intense offensive operations and the necessity of securing one's "lines of operations".[2] German military officers took this to mean as much attention should be given to logistical operations used to fight the war at the rear as those in the front; this most certainly entailed security operations to protect the "lines of operations".[2] Following Jomini's lead, Oberstleutnant Albrecht von Boguslawski published lectures entitled Der Kleine Krieg ("The Small War", a literal translation of guerrilla), which outlined in detail the tactical procedures related to partisan and anti-partisan warfare—likely deliberately written without clear distinctions between combatants and non-combatants.[3] To what extent this contributed to the intensification of unrestrained warfare cannot be known, but Prussian officers like Alfred von Schlieffen encouraged their professional soldiers to embrace a dictum advocating that "for every problem, there was a military solution."[4]

Prussian security operations during the Franco-Prussian War included the use of the Landwehr reservists, whose duties ranged from guarding railroad lines, to taking hostages, and carrying out reprisals to deter activities of the francs-tireurs.[5] Bismarck wanted all francs-tireurs hanged or shot, and encouraged his military commanders to burn down villages that housed them.[6] More formal structures like Chief of the Field Railway, a Military Railway Corps, District Commanders, Special Military Courts, intelligence units, and military police of varying duties and nomenclature were integrated into the Prussian system to bolster security operations all along the military's operational lines.[7] Such was the heritage of German anti-partisan warfare. Operationally, the first attempts to use tactics that would later develop into Bandenbekämpfung or be recognized as such were carried out in China in the wake of the Boxer Rebellion, after two German officers went missing, which was followed up with more than fifty operations by German troops, who set fire to a village and held prisoners. Shortly after these operations, the infantry was provided with a handbook for "operations against Chinese bandits" (Banden).[8] The first full application of Bandenbekämpfung in practice, however, was the Herero and Namaqua genocide, a campaign of racial extermination and collective punishment that the German Empire undertook in German South West Africa (modern-day Namibia) against the Herero and Nama people.[9]

World War I

During the First World War, the German army ignored many of the commonly understood European conventions of war, when between August and October 1914,[a] they deliberately killed some 6,500 French and Belgian citizens.[10] Throughout the war, Germany's integrated intelligence, perimeter police, guard network, and border control measures all coalesced to define the German military's security operations.[11] Along the Eastern Front sometime in August 1915, Field Marshal Falkenhayn established a general government over Congress Poland under General von Beseler, creating an infrastructure to support ongoing military operations, which included guards posts, patrols and a security network. Maintaining security meant dealing with Russian prisoners, many of whom tried to sabotage German plans and kill German soldiers, so harsh pacification measures and terror actions were carried out to deal with these partisans (including brutal reprisals against civilians), otherwise known as bandits.[12] Before long, similar practices were being instituted throughout both the Eastern and Western areas of German occupation.[13]

World War II

German army policy for deterring partisan or "bandit" activities against its forces was to strike "such terror into the population that it loses all will to resist."[14] Even before the Nazi campaign in the east had begun, Hitler had already absolved his soldiers from any responsibility for brutality against civilians, expecting his soldiers and police forces to kill anyone that even "looked askance" at the German forces.[14] Much of the partisan warfare became an exercise of anti-Semitism, as military commanders like General Bechtolsheim exclaimed that whenever an act of sabotage was committed and one killed the Jews from that village, then "one can be certain that one has destroyed the perpetrators, or at least those who stood behind them."[14] When the Wehrmacht entered Serbia in 1941, they carried out mass reprisals against partisans by executing Jews there.[15] The commander responsible for combating partisan warfare in 1941, General Böhme, reiterated to the German forces, "that rivers of German blood" had been spilled in Serbia during the First World War and the Wehrmacht should consider any acts of violence there as "avenging these deaths."[16]

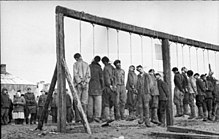

From September 1941 onwards through the course of World War II, the term Bandenbekämpfung supplanted Partisanenkämpfung (anti-partisan warfare) to become the guiding principle of Nazi Germany's security warfare and occupational policies; largely as a result of Heinrich Himmler's insistence that for psychological reasons, bandit was somehow preferable.[17] Himmler charged the 'Prinz Eugen' Division to expressly deal with "partisan revolts."[18] Units like the SS Galizien—who were likewise tasked to deal with partisans—included foreign recruits overseen by experienced German "bandit" fighters well-versed in the "mass murder of unarmed civilians."[19] On 23 October 1942, Himmler named SS General Erich von dem Bach-Zelewski the "Commissioner for anti-bandit warfare."[20] Then Himmler transferred SS-Brigadeführer von Gottberg to Belorussia to ensure that the Bandenbekämpfung operations were conducted on a permanent basis, a task which Gottberg carried out with fanatical ruthlessness, declaring the entire population bandits, Jews, Gypsies, spies, or bandit sympathizers.[20] During Gottberg's first major operations, Operations Nürnberg and Hamburg, conducted between November thru December 1942, he reported 5,000 murdered Jews, another 5,000 bandits or suspects eliminated, and 30 villages burned down.[21]

In October 1942—just a couple months prior to Gottberg's exploits—Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring had ordered "anti-bandit warfare" in Army Group Rear Area Center, which was shortly followed by an OKH Directive on 11 November 1942 for "anti-bandit warfare in the East" that announced sentimental considerations as "irresponsible" and instructed the men to shoot or preferably hang bandits, including women.[21] Misgivings from commanders within Army Group Rear that such operations were counterproductive and in poor taste since women and children were being murdered went ignored or resisted from Bach Zelewski, who frequently "cited the special powers of the Reichsführer."[22] Over time, the Wehrmacht acculturated to the large scale anti-bandit operations, as the enemy was not simply populated by partisan groups, but instead they too came to see the entire population as criminal and complicit in any operation against German troops. In fact, many of the Wehrmacht commanders were unbothered by the fact that these operations fell under the jurisdiction of the SS.[23]

Einsatzgruppen, Order Police, SS-Sonderkommandos and army forces—for the most part—worked cooperatively to combat partisans (bandits), not only acting as judge, jury, and executioners in the field, but also in plundering "bandit areas"; they laid these areas to waste, seized crops and livestock, enslaved the local population or murdered them.[24] Anti-bandit operations were characterized by "special cruelty."[25] For instance, Soviet Jews were murdered outright under the pretext that they were partisans per Hitler's orders.[26] Historian Timothy Snyder asserts that by the second half of 1942, "German anti-partisan operations were all but indistinguishable from the mass murder of the Jews."[27] Other historians have made similar observations. Omer Bartov argued that under the auspices of destroying their "so-called political and biological enemies," often described as "bandits" or "partisans," the Nazis made no effort "to distinguish between real guerrillas, political suspects, and Jews."[28]

Surging operations from better equipped partisans against Army Group Center during 1943 intensified to the degree that the 221st Security Division's did not just eliminate "bandits" but laid entire regions where they operated to waste.[29][b] The scale of this effort must be taken into consideration, as historian Michael Burleigh reports that anti-partisan operations had a significant impact on German operations in the East; namely, since they caused "widespread economic disruption, tied down manpower which could have been deployed elsewhere, and by instilling fear and provoking extreme countermeasures, drove a wedge between occupiers and occupied."[30]

Following the Warsaw Uprising of August 1944, the Nazis intensified their anti-partisan operations in Poland, during which the German forces employed their version of anti-partisan tactics by shooting upwards of 120,000 civilians in Warsaw.[31] Ideologically speaking, since partisans represented an immediate existential threat, in that, they were equated with Jews or people under their influence, the systematic murder of anyone associated with them was an expression of the regime's racial anti-Semitism and was viewed by members of the Wehrmacht as a "necessity of war."[32]

Throughout the war in Europe, and especially during the German-Soviet War, 1941–45, these doctrines amalgamated with the Nazi regime's genocidal plans for the racial reshaping of the Eastern Europe to secure "living space" (Lebensraum) for Germany. In the first eleven months of the war against the Soviet Union, the German forces liquidated in excess of 80,000 "alleged" partisans.[33] Implemented by units of the SS, Wehrmacht and Order Police, Bandenbekämpfung as applied by the Nazi regime and directed by the SS across occupied Europe led to mass crimes against humanity and was an instrumental part of the Holocaust.[34]

Führer Directive 46

In July 1942, Heinrich Himmler, the head of the SS, was appointed to lead the security initiatives in rear areas. One of his first actions in this role was the prohibition of the use of "partisan" to describe counter-insurgents.[35] Bandits (Banden) was the term chosen to be used by German forces instead.[36] Hitler insisted that Himmler was "solely responsible" for combating bandits except in districts under military administration; such districts were under the authority of the Wehrmacht.[36] The organisational changes, putting experienced SS killers in charge, and language that criminalised resistance, whether real or imagined, presaged the transformation of security warfare into massacres.[37]

The radicalisation of "anti-bandit" warfare saw further impetus in the Führer Directive 46 of 18 August 1942, where security warfare's aim was defined as "complete extermination". The directive called on the security forces to act with "utter brutality", while providing immunity from prosecution for any acts committed during "bandit-fighting" operations.[38]

The directive designated the SS as the organisation responsible for rear-area warfare in areas under civilian administration. In areas under military jurisdiction (the Army Group Rear Areas), the Army High Command had the overall responsibility. The directive declared the entire population of "bandit" (i.e. partisan-controlled) territories as enemy combatants. In practice, this meant that the aims of security warfare was not pacification, but complete destruction and depopulation of "bandit" and "bandit-threatened" territories, turning them into "dead zones" (Tote Zonen).[38]

See also

- Myth of the clean Wehrmacht

- Waffen-SS in popular culture

- Hitler's Bandit Hunters: The SS and the Nazi Occupation of Europe

- Marching into Darkness: The Wehrmacht and the Holocaust in Belarus

References

Notes

- ^ A more thorough examination of the German Army's crimes during the First World War can be found in the following work: Horne, John and Alan Kramer. German Atrocities, 1914: A History of Denial. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2001.

- ^ This practice was in keeping with Führer Directive 46, where once pro-bandit areas were turned into "dead zones" by the German forces.

Citations

- ^ Hale 2011, p. 41.

- ^ a b c Blood 2006, p. 5.

- ^ Blood 2006, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Blood 2006, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Blood 2006, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Wawro 2009, p. 279.

- ^ Blood 2006, pp. 12–14.

- ^ Blood 2006, p. 15.

- ^ Blood 2006, pp. 16–18.

- ^ Blood 2006, p. 20.

- ^ Blood 2006, p. 21.

- ^ Blood 2006, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Blood 2006, pp. 24–25.

- ^ a b c Snyder 2010, p. 234.

- ^ Gregor 2008, p. 7.

- ^ Gregor 2008, p. 17.

- ^ Heer 2000, pp. 112–113.

- ^ Hale 2011, p. 275.

- ^ Hale 2011, p. 314.

- ^ a b Heer 2000, p. 113.

- ^ a b Heer 2000, p. 114.

- ^ Heer 2000, p. 115.

- ^ Heer 2000, pp. 118–119.

- ^ Shepherd 2016, pp. 364–367.

- ^ Messerschmidt 2000, p. 394.

- ^ Evans 2010, p. 263.

- ^ Snyder 2010, p. 240.

- ^ Bartov 1991, p. 83.

- ^ Shepherd 2004, p. 166.

- ^ Burleigh 1997, p. 103.

- ^ Snyder 2015, p. 273.

- ^ Fritze 2014, pp. 79–80.

- ^ Bessel 2006, p. 128.

- ^ Hale 2011, p. xx.

- ^ Longerich 2012, pp. 626–627.

- ^ a b Longerich 2012, p. 627.

- ^ Westermann 2005, pp. 191–192.

- ^ a b Geyer & Edele 2009, p. 380.

Bibliography

- Bartov, Omer (1991). Hitler's Army: Soldiers, Nazis, and War in the Third Reich. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19506-879-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bessel, Richard (2006). Nazism and War. New York: Modern Library. ISBN 978-0-81297-557-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Blood, Philip W. (2006). Hitler's Bandit Hunters: The SS and the Nazi Occupation of Europe. Potomac Books. ISBN 978-1-59797-021-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Burleigh, Michael (1997). Ethics and Extermination: Reflections on Nazi Genocide. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-52158-816-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Evans, Richard (2010). The Third Reich at War. New York: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14311-671-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fritze, Lothar (2014). "Did the National Socialists Have a Different Morality?". In Wolfgang Bialas; Lothar Fritze (eds.). Nazi Ideology and Ethics. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars. ISBN 978-1-44385-422-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Geyer, Michael; Edele, Mike (2009). "States of Exception: The Nazi-Soviet War as a System of Violence, 1939–1945". In Geyer, Michael; Fitzpatrick, Sheila (eds.). Beyond Totalitarianism: Stalinism and Nazism Compared. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-89796-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gregor, Neil (2008). "Nazism–A Political Religion". In Neil Gregor (ed.). Nazism, War and Genocide. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. ISBN 978-0-85989-806-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hale, Christopher (2011). Hitler's Foreign Executioners: Europe's Dirty Secret. The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-5974-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Heer, Hannes (2000). "The Logic of the War of Extermination: The Wehrmacht and the Anti-Partisan War". In Hannes Heer; Klaus Naumann (eds.). War of Extermination: The German Military in World War II. New York: Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-1-57181-232-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Messerschmidt, Manfred (2000). "Forward Defense: The "Memorandum of the Generals" for the Nuremberg Court". In Hannes Heer; Klaus Naumann (eds.). War of Extermination: The German Military in World War II. New York: Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-1-57181-232-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Longerich, Peter (2012). Heinrich Himmler. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199592326.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Shepherd, Ben H. (2004). War in the Wild East: The German Army and Soviet Partisans. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-67401-296-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Shepherd, Ben H. (2016). Hitler's Soldiers: The German Army in the Third Reich. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-30017-903-3.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Snyder, Timothy (2010). Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-46503-147-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Snyder, Timothy (2015). Black Earth: The Holocaust as History and Warning. New York: Tim Duggan Books. ISBN 978-1-10190-345-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wawro, Geoffrey (2009). The Franco-Prussian War: The German Conquest of France in 1870–1871. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-52161-743-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Westermann, Edward B. (2005). Hitler's Police Battalions: Enforcing Racial War in the East. Kansas City: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-1724-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)