Battle of Magdala

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2013) |

| Battle of Magdala | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the 1868 Expedition to Abyssinia | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| Abyssinia | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Robert Napier | Tewodros II | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 13,000[1] | 9,000[citation needed] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 20 wounded (2 fatally)[1] |

700 killed[1] 1,200 wounded[1] | ||||||

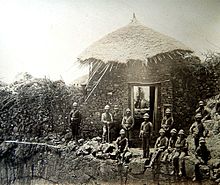

The Battle of Magdala was fought in April 1868 between British and Abyssinian forces at Magdala, 390 miles (630 km) from the Red Sea coast, which at that time was the capital city of Abyssinia (now known as Ethiopia). The British were led by Robert Napier, while the Abyssinians were led by Emperor Tewodros II.

In March 1866 a British envoy had been dispatched to secure the release of a group of missionaries who had first been seized when a letter Tewodros II had sent to Queen Victoria requesting munitions and military experts from the British, delivered by an envoy, Captain Cameron, had gone unanswered. They were released; however Tewodros II changed his mind and sent a force after them and they were returned to the fortress and imprisoned again, along with Captain Cameron.

The British won the battle, and Tewodros committed suicide as the fortress was finally seized.

Preparation and formation

Advance elements of the British military units arrived at Annesley Bay on 4 December 1867; but did not disembark until 7 December due to chaotic conditions on shore.[2] Thousands of mules had been sent from Egypt and other countries before adequate arrangements had been made to feed and water them and the freshly arrived troops had to first obtain fresh feed and water for them. A base camp was set up at Zula.

The British were dressed in new khaki drill jackets with a white cloth-covered cork helmet called a 'Topi'. They had been issued with the new breech-loading Snider-Enfield rifles the previous year, which had increased the soldiers' firepower from three rounds per minute to ten rounds per minute.

Lord Napier arrived in early January 1868 and the expedition started from the advance camp at Senafe at the beginning of February. It took two months to reach their objective. The advancing British forces' route took them through rough terrain, traveling by way of Kumayli, Senafe, Adigrat, Antalo, passing west of Lake Ashangi, through the Wajirat Mountains and across the Wadla plateau, before finally arriving via the road Emperor Tewodros built through the Zhitta Ravine to move his heavy artillery to Magdala.[3]

Composed of some 12,000 British and Indian troops, beside Royal Artillery and Royal Engineers, the field force comprised:

British: 3rd (The Prince of Wales's) Dragoon Guards, the 4th (King's Own) Regiment of Foot, 33rd Regiment of Foot (1st West Riding Regiment). Six companies of infantry from the 45th Nottinghamshire Regiment (Sherwood Foresters) and a Royal Navy rocket battery. The Armstrong Artillery Battery, complete with elephants carrying their guns, joined the expedition on the plain at Talanta on 5 April, just 12 miles (19 km) from Magdala during a delay of four days waiting for supplies to arrive. Towards the end of the campaign the 26th (Cameronian) Regiment of Foot also arrived.

Indian: 10th Regt of Bengal Cavalry (Lancers), 12th Regt of Bengal Cavalry, 3rd Regt of Bombay Lt Cavalry, 21st Punjab Regt Bengal Native Infantry, 23rd Punjab Regt Bengal Native Infantry (Pioneers), 2nd Bombay Native Infantry (Grenadier), 3rd Bombay Native Infantry, 10th Bombay Native Infantry, 21st Bombay Native Infantry (Marine), 25th Bombay Native Light Infantry, 27th Bombay Native Infantry (1st Belooch), No 1 Company of Bombay Native Artillery, Corps of Madras Sappers and Miners, Corps of Bombay Sappers and Miners.

While it is difficult to obtain an accurate order of battle of the Abyssinian forces, from British reports it appears to have consisted of a small amount of artillery and several thousands of light infantry lacking firearms.

The battle

Before the force could actually attack Magdala, they had to get past the plateau at Arogye, which lay across the only route to Magdala. It certainly looked formidable to attack. The British could see the way barred by many thousands of armed Abyssinians camped around the hillsides with up to 30 artillery pieces.

The British did not expect that the Abyssinian warriors would leave their defences to attack them and paid little regard to their defensive positions as they formed up to deploy. But the Emperor did order an attack, with many thousands of soldiers armed with little more than spears. The 4th Regiment of Foot quickly redeployed to meet the charging mass of warriors and poured a devastating fire into their ranks. When two Indian infantry regiments contributed their firepower, the onslaught became even more devastating. Despite this, the Abyssinian soldiers continued their attack, losing over 500 with thousands more wounded during the ninety minutes of fighting, most of them at a point little over 30 yards from the British lines. During the chaotic battle, an advance guard unit of the 33rd Regiment overpowered some of the Abyssinian artillerymen and captured their artillery pieces. The surviving Abyssinian soldiers then retreated back onto Magdala.

In his despatch to London, Lord Napier reported: "Yesterday morning (we) descended three thousand nine hundred feet to Bashilo River and approached Magdala with First Brigade to reconnoitre it. Theodore opened fire with seven guns from outwork, one thousand feet above us, and three thousand five hundred men of the garrison made a gallant sortie which was repulsed with very heavy loss and the enemy driven into Magdala. British Loss, twenty wounded."

Two of the British soldiers wounded in the attack would later die from their injuries.

The following day as the British force moved on to Magdala. Writing later, Clements Markham recalled "a curious phenomenon" that occurred on the day of the final assault: "Early in the forenoon a dark-brown circle appeared round the sun, like a blister, about 15° in radius; light clouds passed and repassed over it, but it did not disappear until the usual rain-storm came up from the eastward late in the afternoon. Walda Gabir, the king's valet, informed me that Theodore saw it when he came out of his tent that morning, and that he remarked that it was an omen of bloodshed."[4]

Tewodros II sent two of the hostages on parole to offer terms. Napier insisted on the release of all the hostages and an unconditional surrender. Tewodros refused to cede to the unconditional surrender, but did release the European hostages. The British continued the advance and assaulted the fortress. (The native hostages were later found to have had their hands and feet cut off before being sent over the edge of the precipice surrounding the plateau.)[5]

The bombardment began with mortars, rockets and artillery. Infantry units then opened fire, covering the Royal Engineers sent to blow up the gates of the fortress. The path lay up a steep boulder-strewn track, on one side of which there was a sheer drop and on the other a perpendicular cliff face, leading to the main gateway, known as the Koket-Bir, which included thick timber doors set into a 15-foot-long (4.6 m) stone archway. Each side of the gate was protected by a thorn-and-stake hedge. After this gate was a further uphill path to a second fortified gateway, which led onto the final plateau or amba.

On reaching the gate there was a pause in the advance, as it was discovered the engineer unit had forgotten their powder kegs and scaling ladders and were ordered to return for them. General Staveley was not happy at any further delay and ordered the 33rd Regiment to continue the attack. Several officers and the men of the 33rd, along with an officer from the Royal Engineers, parted from the main force and, after climbing the cliff face, found their way blocked by a thorny hedge over a wall. Private James Bergin, a very tall man, used his bayonet to cut a hole in the hedge and Drummer Michael Magner climbed onto his shoulders and through the gap in the hedge and dragged Private Bergin up behind him as Ensign Conner and Corporal Murphy helped shove from below. Bergin kept up a rapid rate of fire on the Koket-Bir as Magnar dragged more men through the gap in the hedge.

As more men poured through and opened fire, as they advanced with their bayonets fixed, the defenders withdrew through the second gate. The party rushed the Koket-bir before it was fully closed and then took the second gate, breaking through to the amba. Ensign Wynter scrambled up onto the top of the second gate and fixed the 33rd Regimental Colours to show the plateau had been taken. Private Bergin and Drummer Magner were later awarded the Victoria Cross for their part in the action.[6]

Tewodros II was found dead inside the second gate, having shot himself with a pistol that had been a gift from Queen Victoria. When his death was announced, all resistance ceased. His body was cremated and buried inside the church by the priests. The church was guarded by soldiers from the 33rd Regiment[7] although, according to Henry M. Stanley, looted of "an infinite variety of gold, and silver and brass crosses"[8] along with filigree works and rare tabots.

Aftermath

On 19 April, having first blown up the fortress and burned the city, Napier commenced the return march. According to historian Richard Pankhurst, fifteen elephants and almost two hundred mules were required to bear the loot across the Bashilo River to the nearby Dalanta Plain. A grand review was held, and then an auction of the loot; the money raised was distributed amongst the troops and no written list was made of who purchased the various items. Some books and artifacts held aside from the auction were presented to the Queen, whilst others were taken by the troops and officers, but not classed as loot. The British Museum, the British Library and the Victoria and Albert Museum as well as the Queen's library at Windsor Castle. are just a few of the British institutes that hold items that were looted.[9][10]

For the victory in the campaign Lieutenant-General Napier was ennobled by Queen Victoria, and became Baron Napier of Magdala.

Since 2000 AD the AFROMET (Association For the Return Of the Madgala Ethiopian Treasures) campaign has been lobbying for the return of these objects to Ethiopia.

Officers and soldiers who took part in the campaign were awarded the Abyssinian War Medal.

See also

References

- ^ a b c d Ferguson, p. 177

- ^ Brereton and Savoury, p. 184

- ^ This course was described within a few months and in careful detail by Markham, Clements (1868). "Geographical Results of the Abyssinian Expedition". Journal of the Royal Geographical Society. 38: 12–49. doi:10.2307/1798567. JSTOR 1798567.

- ^ Markham, "Geographical Results", p. 48

- ^ Brereton and Savoury, p. 189

- ^ "No. 23405". The London Gazette. 28 July 1868.

- ^ Our Soldiers, by W.H.G. Kingston - Battle of Magdala, page 194

- ^ Pankhurst, Richard. "Maqdala and its loot". Institute of Ethiopian Studies. Retrieved 8 July 2008.

- ^ http://www.elginism.com/similar-cases/the-magdala-treasures-in-the-british-museum/20100222/2753/

- ^ http://www.elginism.com/similar-cases/the-magdala-treasures-in-the-british-museum/20100222/2753/#sthash.pfmfTVwY.dpuf

Works cited

- Brereton, J. M.; Savoury, A. C. S. History of the Duke of Wellington's Regiment. ISBN 0-9521552-0-6.

- Ferguson, Niall. Empire: How Britain made the Modern World.