Before the Revolution

| Before the Revolution | |

|---|---|

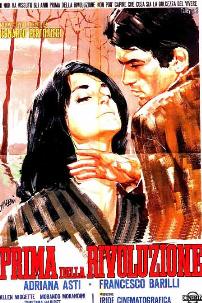

Film poster | |

| Directed by | Bernardo Bertolucci |

| Written by | Bernardo Bertolucci Gianni Amico |

| Starring | Adriana Asti Francesco Barilli |

| Cinematography | Aldo Scavarda |

| Edited by | Roberto Perpignani |

| Music by | Ennio Morricone |

| Distributed by | New Yorker Films (US, 1965) |

Release date |

|

Running time | 115 minutes |

| Country | Italy |

| Language | Italian |

Before the Revolution (Template:Lang-it) is a 1964 Italian romantic drama film directed by Bernardo Bertolucci. It stars Adriana Asti and Francesco Barilli and is centred on "political and romantic uncertainty among the youth of Parma".[1]

The film, strongly influenced by the French New Wave, was shot between September and November, 1963. The shooting took place in Parma and its surroundings, one scene being filmed in the camera ottica (optical chamber) at the Sanvitale Fortress in Fontanellato. It premiered on 9 May 1964 at the 17th Cannes Film Festival during the International Critics' Week. Although the initial reception was only lukewarm, it has since become widely respected by critics, praised for its technical merit and music and is included in the book in the book 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die, where Colin MacCabe refers to it as "the perfect portrait of the generation who were to embrace revolt in the late 1960s". A retrospective of the film was given at the BFI Southbank in London.

Plot

Parma, 1962. Fabrizio (Francesco Barilli) a young student, struggles with reconciling middle class life with his interest in the militant views of the Italian Communist Party. He has a serious discussion his best friend Agostino (Allen Midgette) who tells him of his hatred for his parents' way of life. He is caught between relying on the Catholicism of his parents and the Marxist ideas touted by Fabrizio.

Fabrizio is shocked when he learns of Agostino's drowning in the Po River. He interviews local youths who were there when it happened and becomes convinced that Agostino committed suicide. Fabrizio imagines that his friend's hatred for his parents was really hatred of himself. His despair causes him to break up with his girlfriend Clelia (Cristina Pariset), an apolitical, but pretty girl from a respectable family who he associates with the middle class life he's now desperate to avoid. His sudden restlessness causes his parents to invite his mother's beautiful younger sister Gina (Adriana Asti) from Milan to stay with family. After some discussion about death and the meaning of life, Fabrizio and Gina begin a passionate sexual relationship. Fabrizio introduces Gina to his former teacher Cesare (Morando Morandini), who is responsible for his interest in Communism. They read from various philosophical works and reflect on Italy's fascist past.

Later Fabrizio runs into Gina coming out of a hotel with a man she met in the street. After harshly confronting her, Fabrizio leaves angrily. Gina sobs on the phone to her psychoanalyst about her inability to sleep and her constant anxieties. Although we only hear her side of the conversation, it's clear she has had some serious mental health issues. It is implied that her trip to Parma was suggested by her therapist to help her get away from problems at home. Fabrizio tries to distract himself by going to the movies with a friend who waxes poetic about how morality can be expressed through camera angles.

Fabrizio and Gina spend the day with Puck (Cecrope Barilli), an old lover and friend of Gina's who has been living off land owned by his father his entire life and has never held a job. He is unashamed because he's a creature of habit. This strikes a chord in Fabrizio (jealous of Gina and Puck's intimacy) who lashes out at Puck. Gina slaps him for being rude to her friend. Fabrizio realizes that Puck is himself in 30 years. Children of the bourgeoisie cannot ever escape their past. Gina returns to Milan shortly thereafter.

Left alone, Fabrizio becomes more conscious of his own weaknesses and his inability to realize his aspirations and political ambitions. He finally disavows the Communism revolution and chooses to go along with what is expected of him. He vows to forget politics and his Aunt Gina and marries his former girlfriend Clelia. Years later, Fabrizio and his wife run into Gina outside the opera. He is amazed to discover that she still affects him in the same way. Gina takes him by the hand and leads him back to his wife and quickly walks away.

Cast

- Adriana Asti as Gina

- Francesco Barilli as Fabrizio

- Allen Midgette as Agostino

- Morando Morandini as Cesare

- Cristina Pariset as Clelia

- Cecrope Barilli as Puck

- Evelina Alpi as the little girl

- Gianni Amico as a friend

- Goliardo Padova as the painter

Background and production

The title of the film is derived from a saying by Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord: "Only those who lived before the revolution knew how sweet life could be".[2] The names of the characters in the film are the same as those in Stendhal's novel La Charteuse de Parme:[3] the principal character and narrator, Fabrice, is now Fabrizio del Dongo, a young Marxist from a bourgeois family, who attracts his young aunt, Gina, now Gina Sanseverina, and finally marries a girl from a good family, Clélia, now Clelia Conti.

Bertolucci said of the context of the film in a 1996 interview:

"I have a different fever... a nostalgia for the present. Each moment seems remote, even as I live it. I don't want to exchange the present. I accept it, but my bourgeois future is my bourgeois past. For me, ideology was something of a holiday. I thought I was living the revolution. Instead I lived the years before the revolution. Because, for my sort it's always before the revolution".[4]

The film, strongly influenced by the French New Wave,[5] was shot between September and November 1963. The shooting took place in Parma and its surroundings, one scene being filmed in the camera ottica (optical chamber) at the Sanvitale Fortress in Fontanellato.[6]

Themes

Like Marco Bellocchio's Fists in the Pocket (I pugni in tasca), which was released the following year, Before the Revolution is considered a precursor of the protests of 1968.[7] Luana Ciavola, author of Revolutionary Desire in Italian Cinema, believes that like I pugni in tasca, the film gives the impression of coming from within the bourgeoisie, but at the same time being against it, although notes that the way it approaches revolt differs. He writes of it: "In Prima della rivoluzione the revolt of the protagonist finds support in political commitment. Sustained by an erotic desire, the revolt is fostered by the political ideology that provies a raison d'etre as well as a symbolic terrain through which to articulate the revolt. Even more, the ideology, embodied by Cesare, provides Fabrizio with a superior meaning with which to confront and shape his rebel self. Through ideology, Fabrizio spells out and clarifies his course of revolt and singularity of rebel subject, and eventually his desire for revolt".[7] David Jenkins, the critic from TimeOut, noted as that as in "all of Bertolucci's movies, there's a central conflict between the 'radical' impulses and a pessimistic (and/or willing) capitulation to the mainstream of bourgeois society and culture".[1]

Eugene Archer of The New York Times believes that Bertolucci attempted a "symbolic autobiography" in his classical construction of the film. She highlights loss and defeat as notable themes, with the failure at love symbolizing "a death of the past, an angst-ridden sense of futility in any kind of revolutionary striving, whether emotional, political or merely intellectual, amid the defeat of contemporary society".[2] Peter Bradshaw of The Guardian notes that the film displays a "distinctively patrician concern with Catholicism and Marxism".[5] One critic noted how "Bertolucci uses poetic sounds and images to try to communicate emotions and ideas, rather than plot, such as in the disturbing final scene where Fabrizio and Clelia's wedding is intercut with Cesare reading "Moby Dick" to a class of youngsters, as a tearful Gina hugs and kisses".[8]

Release and reception

Before the Revolution premiered on 12 May 1964 at the 17th Cannes Film Festival during the International Critics' Week.[9] Although it is now seen as belonging to the Italian Nouvelle Vague,[10] Before the Revolution did not attract large audiences in Italy where it only received lukewarm approval from most of the critics. It did however enjoy an enthusiastic reception abroad. It has since become widely acclaimed by critics, and praised for its technical merit, although generally not viewed quite as well as some of Bertolucci's later films, due to his young age and lack of experience at time.[8][11]

The film is cited as "one of the masterpieces of Italian cinema" by Film4, and it is featured in the book 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die, where Colin MacCabe refers to it as "the perfect portrait of the generation who were to embrace revolt in the late 1960s, and a stunning portrait of Parma—Bertolucci's own city".[12] As of May 2015, it has a 92% rating on Rotten Tomatoes, based on 11 reviews.[13] A retrospective of the film was given at the BFI Southbank in London.[11] Eugene Archer of The New York Times notes that Bertolucci used many cinematic references in the film to Italian and French realist master directors such as Roberto Rossellini and Alain Resnais, and managed to "assimilate a high degree of filmic and literary erudition into a distinctively personal visual approach", showing "outstanding promise" as a filmmaker.[2]

David Jenkins of TimeOut, was less favorable, and stated that although it is a "leisurely, verbose and stylish film made by thinkers for thinkers, the film "feels like it’s caught between two stools: it lacks the acute social observation found in Bertolucci’s stunning debut, The Grim Reaper (1963), but it also fails to achieve the levels of free-flowing fizz displayed in his follow-up, Partner (1968)". He did, however, praise "the virtuoso camerawork, Ennio Morricone’s rippling score and the melancholy reminder that for the young and politically engaged, the ‘revolution’ is always just over the horizon".[1]

References

- ^ a b c Jenkins, David. "Before the Revolution". TimeOut. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b c "Before the Revolution". The New York Times. 25 September 1964. Retrieved 10 May 2015.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Kline, Thomas Jefferson (1987). Bertolucci's dream loom: a psychoanalytic study of cinema. University of Massachusetts Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-87023-569-6.

- ^ Guan, Yeoh Seng (25 February 2010). Media, Culture and Society in Malaysia. Routledge. p. 221. ISBN 978-1-135-16928-2.

- ^ a b "Before the Revolution – review". The Guardian. 7 April 2011. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Bertozzi, Marco (2008). Storia del documentario italiano: immagini e culture dell'altro cinema. Marsilio. p. 22. ISBN 978-88-317-9553-1.

- ^ a b Ciavola, Luana (2011). Revolutionary Desire in Italian Cinema. Troubador Publishing Ltd. pp. 77–78. ISBN 978-1-84876-680-8.

- ^ a b "Before the Revolution". TV Guide. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Gratis a vedere Bertolucci: le date delle proiezioni" (in Italian). Parma.repubblica.it. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- ^ Aitken, Ian (2001). European Film Theory and Cinema: A Critical Introduction. Edinburgh University Press. p. 240. ISBN 978-0-7486-1168-3.

- ^ a b French, Philip (10 April 2011). "Before the Revolution". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Schneider, Steven Jay (1 October 2012). 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die 2012. Octopus Publishing Group. p. 432. ISBN 978-1-84403-733-9.

- ^ "Before the Revolution". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 19 May 2015.