Beltrami–Klein model

In geometry, the Beltrami–Klein model, also called the projective model, Klein disk model, and the Cayley–Klein model, is a model of hyperbolic geometry in which points are represented by the points in the interior of the unit disk (or n-dimensional unit ball) and lines are represented by the chords, straight line segments with ideal endpoints on the boundary sphere.

The Beltrami–Klein model is named after the Italian geometer Eugenio Beltrami and the German Felix Klein while "Cayley" in Cayley–Klein model refers to the English geometer Arthur Cayley.

The Beltrami–Klein model is analogous to the gnomonic projection of spherical geometry, in that geodesics (great circles in spherical geometry) are mapped to straight lines.

This model is not conformal, meaning that angles and circles are distorted, whereas the Poincaré disk model preserves these.

In this model, lines and segments are straight Euclidean segments, whereas in the Poincaré disk model, lines are arcs that meet the boundary orthogonally.

History

This model made its first appearance for hyperbolic geometry in two memoirs of Eugenio Beltrami published in 1868, first for dimension n = 2 and then for general n, these essays proved the equiconsistency of hyperbolic geometry with ordinary Euclidean geometry.[1][2][3]

The papers of Beltrami remained little noticed until recently and the model was named after Klein ("The Klein disk model"). This happened as follows. In 1859 Arthur Cayley used the cross-ratio definition of angle due to Laguerre to show how Euclidean geometry could be defined using projective geometry.[4] His definition of distance later became known as the Cayley metric.

In 1869, the young (twenty-year-old) Felix Klein became acquainted with Cayley's work. He recalled that in 1870 he gave a talk on the work of Cayley at the seminar of Weierstrass and he wrote:

- "I finished with a question whether there might exist a connection between the ideas of Cayley and Lobachevsky. I was given the answer that these two systems were conceptually widely separated."[citation needed]

Later, Felix Klein realized that Cayley's ideas give rise to a projective model of the non-Euclidean plane.[5]

As Klein puts it, "I allowed myself to be convinced by these objections and put aside this already mature idea." However, in 1871, he returned to this idea, formulated it mathematically, and published it.[6]

Distance formula

The distance function for the Beltrami–Klein model is a Cayley–Klein metric. Given two distinct points p and q in the open unit ball, the unique straight line connecting them intersects the boundary at two ideal points, a and b, label them so that the points are, in order, a, p, q, b and |aq| > |ap| and |pb| > |qb|.

The hyperbolic distance between p and q is then:

The vertical bars indicate Euclidean distances between the points between them in the model, log is the natural logarithm and the factor of one half is needed to give the model the standard curvature of −1.

When one of the points is the origin and Euclidean distance between the points is r then the hyperbolic distance is:

- Where artanh is the inverse hyperbolic function of tangens hyperbolico.

The Klein disk model

In two dimensions the Beltrami–Klein model is called the Klein disk model. It is a disk and the inside of the disk is a model of the entire hyperbolic plane. Lines in this model are represented by chords of the boundary circle (also called the absolute). The points on the boundary circle are called ideal points; although well defined, they do not belong to the hyperbolic plane. Neither do points outside the disk, which are sometimes called ultra ideal points.

The model is not conformal, meaning that angles are distorted, and circles on the hyperbolic plane are in general not circular in the model. Only circles that have their centre at the centre of the boundary circle are not distorted. All other circles are distorted, as are horocycles and hypercycles

Properties

Chords that meet on the boundary circle are limiting parallel lines.

Two chords are perpendicular if, when extended outside the disk, each goes through the pole of the other. (The pole of a chord is an ultra ideal point: the point outside the disk where the tangents to the disk at the endpoints of the chord meet.) Chords that go through the centre of the disk have their pole at infinity, orthogonal to the direction of the chord (this implies that right angles on diameters are not distorted).

Compass and straightedge constructions

Here is how one can use compass and straightedge constructions in the model to achieve the effect of the basic constructions in the hyperbolic plane.

- The pole of a line. While the pole is not a point in the hyperbolic plane (it is an ultra ideal point) most constructions will use the pole of a line in one or more ways.

- For a line: construct the tangents to the boundary circle through the ideal (end) points of the line. the point where these tangents intersect is the pole.

- For diameters of the disk: the pole is at infinity perpendicular to the diameter.

- To construct a perpendicular to a given line through a given point draw the ray from the pole of the line through the given point. The part of the ray that is inside the disk is the perpendicular.

- When the line is a diameter of the disk then the perpendicular is the chord that is (Euclidean) perpendicular to that diameter and going through the given point.

- To find the midpoint of given segment : Draw the lines through A and B that are perpendicular to . (see above) Draw the lines connecting the ideal points of these lines, two of these lines will intersect the segment and will do this at the same point. This point is the (hyperbolic) midpoint of.[7]

- To bisect a given angle : Draw the rays AB and AC. Draw tangents to the circle where the rays intersect the boundary circle. Draw a line from A to the point where the tangents intersect. The part of this line between A and the boundary circle is the bisector.[8]

- The common perpendicular of two lines is the chord that when extended goes through both poles of the chords.

- When one of the chords is a diameter of the boundary circle then the common perpendicular is the chord that is perpendicular to the diameter and that when lengthened goes through the pole of the other chord.

- To reflect a point P in a line l: From a point R on the line l draw the ray through P. Let X be the idealpoint where the ray intersects the absolute. Draw the ray from the pole of line l through X, let Y be the other intersection point with the absolute. Draw the segment RY. The reflection of point P is the point where the ray from the pole of line l through P intersects RY.[9]

Circles, hypercycles and horocycles

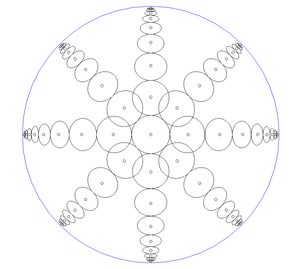

While lines in the hyperbolic plane are easy to draw in the Klein disk model, it is not the same with circles, hypercycles and horocycles.

Circles (the set of all points in a plane that are at a given distance from a given point, its center) in the model become ellipses increasingly flattened as they are nearer to the edge. Also angles in the Klein disk model are deformed.

For constructions in the hyperbolic plane that contain circles, hypercycles, horocycles or non right angles it is better to use the Poincaré disk model or the Poincaré half-plane model.

Relation to the Poincaré disk model

Both the Poincaré disk model and the Klein disk model are models of the hyperbolic plane. An advantage of the Poincaré disk model is that it is conformal (circles and angles are not distorted); a disadvantage is that lines of the geometry are circular arcs orthogonal to the boundary circle of the disk.

The two models are related through a projection on or from the hemisphere model. The Klein model is an orthographic projection to the hemisphere model while the Poincaré disk model is a stereographic projection.

When projecting the same lines in both models on one disk both lines go through the same two ideal points.(the ideal points remain on the same spot) also the pole of the chord is the centre of the circle that contains the arc.

If P is a point a distance from the centre of the unit circle in the Beltrami–Klein model, then the corresponding point on the Poincaré disk model a distance of u on the same radius:

Conversely, If P is a point a distance from the centre of the unit circle in the Poincaré disk model, then the corresponding point of the Beltrami–Klein model is a distance of s on the same radius:

Distance and metric tensor

Given two distinct points U and V in the open unit ball of the model in Euclidean space, the unique straight line connecting them intersects the unit sphere at two ideal points A and B, labeled so that the points are, in order along the line, A, U, V, B. Taking the centre of the unit ball of the model as the origin, and assigning position vectors u, v, a, b respectively to the points U, V, A, B, we have that that ‖a − v‖ > ‖a − u‖ and ‖u − b‖ > ‖v − b‖, where ‖ · ‖ denotes the Euclidean norm. Then the distance between U and V in the modelled hyperbolic space is expressed as

where the factor of one half is needed to make the curvature −1.

The associated metric tensor is given by

Relation to the hyperboloid model

The hyperboloid model is a model of hyperbolic geometry within (n + 1)-dimensional Minkowski space. The Minkowski inner product is given by

and the norm by . The hyperbolic plane is embedded in this space as the vectors x with ‖x‖ = 1 and x0 (the "timelike component") positive. The intrinsic distance (in the embedding) between points u and v is then given by

This may also be written in the homogeneous form

which allows the vectors to be rescaled for convenience.

The Beltrami–Klein model is obtained from the hyperboloid model by rescaling all vectors so that the timelike component is 1, that is, by projecting the hyperboloid embedding through the origin onto the plane x0 = 1. The distance function, in its homogeneous form, is unchanged. Since the intrinsic lines (geodesics) of the hyperboloid model are the intersection of the embedding with planes through the Minkowski origin, the intrinsic lines of the Beltrami–Klein model are the chords of the sphere.

Relation to the Poincaré ball model

Both the Poincaré ball model and the Beltrami–Klein model are models of the n-dimensional hyperbolic space in the n-dimensional unit ball in Rn. If is a vector of norm less than one representing a point of the Poincaré disk model, then the corresponding point of the Beltrami–Klein model is given by

Conversely, from a vector of norm less than one representing a point of the Beltrami–Klein model, the corresponding point of the Poincaré disk model is given by

Given two points on the boundary of the unit disk, which are traditionally called ideal points, the straight line connecting them in the Beltrami–Klein model is the chord between them, while in the corresponding Poincaré model the line is a circular arc on the two-dimensional subspace generated by the two boundary point vectors, meeting the boundary of the ball at right angles. The two models are related through a projection from the center of the disk; a ray from the center passing through a point of one model line passes through the corresponding point of the line in the other model.

See also

Notes

- ^ Beltrami, Eugenio (1868). "Saggio di interpretazione della geometria non-euclidea". Giornale di Mathematiche. VI: 285–315.

- ^ Beltrami, Eugenio (1868). "Teoria fondamentale degli spazii di curvatura costante". Annali. di Mat., ser II. 2: 232–255. doi:10.1007/BF02419615.

- ^ Stillwell, John (1999). Sources of hyperbolic geometry (2. print. ed.). Providence: American mathematical society. pp. 7–62. ISBN 0821809229.

- ^ Cayley, Arthur (1859). "A Sixth Memoire upon Quantics". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. 159: 61–91. doi:10.1098/rstl.1859.0004.

- ^ Klein, Felix (1871). "Ueber die sogenannte Nicht-Euklidische Geometrie". Mathematische Annalen. 4: 573–625. doi:10.1007/BF02100583.

- ^ Shafarevich, I. R.; A. O. Remizov (2012). Linear Algebra and Geometry. Springer. ISBN 978-3-642-30993-9.

- ^ hyperbolic toolbox

- ^ hyperbolic toolbox

- ^ Greenberg, Marvin Jay (2003). Euclidean and non-Euclidean geometries : development and history (3rd ed.). New York: Freeman. pp. 272–273. ISBN 9780716724469.

- ^ Hyperbolic Geometry , J.W.Cannon, W. J. Floyd, R. Kenyon, W. R. Parry

- ^ answer from math stackexchange

References

- Luis Santaló (1961), Geometrias no Euclidianas, EUDEBA.

- Stahl, Saul (1993). The Poincaré Half-Plane. Jones and Bartlett.

- Nielsen, Frank; Nock, Richard (2009). "Hyperbolic Voronoi diagrams made easy". arXiv:0903.3287.