Blue catfish

| Blue catfish | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Siluriformes |

| Family: | Ictaluridae |

| Genus: | Ictalurus |

| Species: | I. furcatus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Ictalurus furcatus (Valenciennes, 1840)[1]

| |

| |

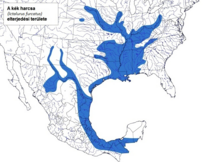

| Native distribution of Ictalurus furcatus | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The blue catfish (Ictalurus furcatus) is the largest species of North American catfish, reaching a length of 165 cm (65 in) and a weight of 68 kg (150 lb). The typical length is about 25–46 in (64–117 cm). The fish can live to 20 years. The native distribution of blue catfish is primarily in the Mississippi River drainage, including the Missouri, Ohio, Tennessee, and Arkansas Rivers, The Des Moines River in South Central Iowa, and the Rio Grande, and south along the Gulf Coast to Belize and Guatemala.[2] These large catfish have also been introduced in a number of reservoirs and rivers, notably the Santee Cooper lakes of Lake Marion and Lake Moultrie in South Carolina, the James River in Virginia, Powerton Lake in Pekin, Illinois, and Lake Springfield in Springfield, Illinois. This fish is also found in some lakes in Florida.[3] The fish is considered an invasive pest in some areas, particularly the Chesapeake Bay. Blue catfish can tolerate brackish water, thus can colonize along inland waterways of coastal regions.[4]

Record-setting fish

On June 18, 2011, Nick Anderson of Greenville, North Carolina reeled in a 143-lb blue catfish from John Kerr Reservoir, more commonly known as Buggs Island Lake, on the Virginia-North Carolina border. On June 22, 2011, the Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries certified the blue catfish as the state's largest, setting a new state record.[5] The fish had a length of 57 in (145 cm) and a girth of 47 in (120 cm).

On February 7, 2012, a 136-lb blue catfish was caught on a commercial-fishing trot line in Lake Moultrie, one of the two Santee Cooper lakes, near Cross, South Carolina. It was 56 inches long. The fish is the largest blue catfish ever weighed on a certified scale in South Carolina, but it is not eligible for state record certification because it was not caught on a rod and reel.

On July 20, 2010, a yet-to-be-certified new world record blue catfish was caught by Greg Bernal of Florissant, Missouri, on the Missouri River. Greg's girlfriend, Janet Momphard, a nurse from St. Charles, helped land the world-record fish. The record catfish weighed in at 130 lb. It was 57 in long and 45 in around. The previous angling world record, 124 lb, was caught by Tim Pruitt on May 22, 2005, in the Mississippi River.[6][7] This record broke the previous blue catfish record of 121.5 lb caught from Lake Texoma, Texas.

Extreme hand-lining expert Zachary Gustafson holds the record for hand-lining in a 107-lb blue catfish on 15-lb-test braided line. The catfish was pulled in on June 5, 2015 on the Potomac River. The record-setting catfish was pulled in using a sausage with a circle hook.[8]

The Indiana record for a blue catfish was set in 1999 by Bruce Midkiff. The fish was caught in the Ohio River and weighed 104 lb.[9]

Identification

Blue catfish are often misidentified as channel catfish. Blue catfish are heavy bodied, blueish gray in color, and have a dorsal hump.[10] The best way to tell the difference between a channel catfish and a blue catfish is to count the number of rays on the anal fin. A blue catfish has 30–36 rays, whereas a channel catfish has 25–29.[10] Blue catfish also have barbels, a deeply forked tail, and a protruding upper jaw.[10]

Diet

Blue catfish are opportunistic predators and eat any species of fish they can catch, along with crawfish, freshwater mussels, frogs, and other readily available aquatic food sources. Catching their prey becomes all the more easy if it is already wounded or dead, and blue catfish are noted for feeding beneath marauding schools of striped bass in open water in reservoirs or feeding on wounded baitfish that have been washed through dam spillways or power-generation turbines. Blue catfish are one of the only species of fish in the Mississippi river basin able to eat adult Asian carp.[11]

Pest status

The ability of the blue catfish to tolerate a wide range of climates and brackish water has allowed it to thrive in Virginia's rivers, lakes, tributaries, and the Chesapeake Bay. Unfortunately, the relatively low mortality rate, large body size, wide range of species preyed upon, and success as a predator has resulted in the blue catfish being considered a problematic invasive species in Virginia. Since their introduction in Virginia waters in the 1970s,[12] blue catfish populations have exploded. Recent electrofishing studies have documented capture rates in excess of 6,000 fish/hr,[12] whereas studies from the native range show peak electrofishing capture rates of 700 fish/hr.[13] Clearly, blue catfish are a dominant species within the freshwater and oligohaline portions of Virginia's tidal rivers. The introduction of blue catfish in Virginia's tidal rivers was thought to have negative impacts on anadromous American shad, blueback herring, and alewife; however, predation of these species by blue catfish has been demonstrated to be minimal.[14] Much of the narrative that has been built around the species as a dangerous apex predator in the Chesapeake Bay is simply not true. Researchers from Virginia Tech have found the species to be mostly herbivorous and omnivorous, with diets consisting largely of hydrilla and Asian clams, both of which are invasive to the Chesapeake Bay.[15] Blue catfish do eat blue crabs with some regularity, which is problematic because blue crabs represent the most valuable fishery in the Chesapeake Bay.[16]

See also

- Flathead catfish (Pylodictis olivaris), another very large North American catfish

- Channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus), a species of North American catfish closely related to the blue catfish

References

- ^ "Ictalurus furcatus". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 11 March 2006.

- ^ Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.). "Ictalurus furcatus". FishBase. December 2011 version.

- ^ Hook and Bullet website, at http://www.hookandbullet.com/fishing-lake-placid-placid-lakes-fl/ .

- ^ Graham, K. (1999) "A review of the biology and Management of Blue Catfish." American Fisheries Society Symposium 24:37–49

- ^ Dixon, Julia (June 22, 2011) News Release 143-Pound Blue Catfish Certified as State Record. Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries.

- ^ Blue catfish receives world record status from the IGFA Archived 2007-03-11 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 5 September 2006

- ^ IDNR Announces World's Largest Blue Catfish Caught Retrieved 5 September 2006 Archived April 27, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Howard. "Handling fishing Zac Gustafson".

- ^ Record Fish Program | Indiana Fishing Regulation Guide. eRegulations.com. Retrieved on 2015-06-18.

- ^ a b c Catfish in Lake Ouachita Archived 2016-04-26 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 1 July 2016

- ^ O'Keefe, Dan (24 February 2015). "Asian carp being eaten by native fish, new studies find". MSU Extension. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- ^ a b Greenlee, R. S., and C. N. Lim. 2011. Searching for equilibrium: population parameters and variable recruitment in introduced Blue Catfish populations in four Virginia tidal river systems. Pages 349-367 in P. H. Michaletz and V. H. Travnichek, editors. Conservation, Ecology, and Management of Catfish, the second international symposium. American Fisheries Society, Symposium 77, Bethesda, Maryland.

- ^ Boxrucker, J., and K. Kuklinski. 2008. Abundance, growth, and mortality of selected Oklahoma Blue Catfish populations: implications for management of trophy fisheries. Proceedings of the Annual Conference Southeastern Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies 60(2006):152–156.

- ^ Schmitt; et al. (2017). "Predation and Prey Selectivity by Nonnative Catfish on Migrating Alosines in an Atlantic Slope Estuary". Marine and Coastal Fisheries. 9: 108–125. doi:10.1080/19425120.2016.1271844.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Virginia Tech. "Research on Blue Catfish in the Chesapeake Bay". Virginia Tech Fluvial Fishes Lab.

- ^ "Blue Crabs in the Chesapeake Bay". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration: Chesapeake Field Office.

Further reading

- Johnson, Ryan (2015). Ryan Believes Everything He Reads. Alamogordo, Texas: Penguin Publishing. ISBN 0-123456-78-9.

- Salmon, M. H. III (1997). The Catfish As A Metaphor. Silver City, New Mexico: High-Lonesome Books. ISBN 0-944383-43-2.

External links

- Blue Catfish Factsheet. USGS

- . Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.

- Blue Catfish Records.