Ayn al-Zara

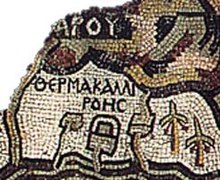

Detail of Madaba map for Callirrhoe | |

| Region | Eastern shore of Dead Sea, Jordan |

|---|---|

| Type | nymphaeum thermae |

| History | |

| Founded | 1st century BCE |

Calirrhoe (Template:Lang-grc) is an archaeological site in Jordan in which remains of a nymphaeum can be traced, though it is considered difficult to be interpreted. Callirrhoe is known in ancient literature for its thermal springs, because it was visited by King Herodes according to Josephus[1] shortly before his death, as a final attempt to be cured or relief his pains. It remains unknown if the greatest builder in Jewish history[2] is related to any of the observable remains in the area. Callirrhoe is referred in the Midrash[3] as well as by Pliny the Elder (Natural History, 70-72), Ptolemaeus (Geography 15,6) and Solinus (De mirabilibus mundi 35,4).[4]

Madaba Map

Callirrhoe is represented on Madaba Map. On the mosaic three constructions can be observed, a spring house, a nymphaeum, and a house.[5] Springs' waters are gathered in basins, and two little palm trees are discerned representing the oasis or the fecundity of this area because of the abundant fresh water supply.[6] Waters of the southern spring sprout from the mountain ending up in the sea.[7]

Archaeological surveys

Recently Callirrhoe was identified as the present day oasis Ayn az-Zara, or Ein ez Zara, laying at the eastern shore of Dead Sea, between Wadi Mujib in the south and Wadi Zerka ma'in in the north, being closer to Wadi Zerka ma'in. It was founded circa 1st century BCE and present day excavations were directed by A. Strobel on behalf of the Deutsches Evangelisches Institut fur Altertumswissenschaft des Heilingen Landes.[8] The remains are hardly interpretable according to H. Donner.[9] A villa of the 1st century CE, uncovered in recent excavations, is considered to be inspired by the designs used by Herodes for his palaces.[10]

Culture

Callirrhoe is included in the so-called bathing culture, known mainly at Indus Valley Civilization,[11] Ancient Greece,[12] Roman Empire,[13] Middle East and Ottoman Empire,[14] Indonesia and Japan[15] for sanitation, therapy and purification purposes.

References

- ^ Joseph. BJ 1.657; AJ 17.171 (Herod) went over Jordan, and made use of the hot waters of Callirrhoe, which run into the lake As-phaltitis, but are themselves sweet enough to be drunk.

- ^ Spino, Ken (Rabbi) (2010). "History Crash Course #31: Herod the Great (online)". Crash Course in Jewish History. Targum Press. ISBN 978-1-5687-1532-2. Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- ^ Genesis R. 37

- ^ Avi-Yonah, Michael (1954). The Madaba Mosaic Map with Introduction and Commentary. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society. p. 40.

- ^ "CALLIRRHOE (Uyun es-Sara) Jordan". The Princeton encyclopedia of classical sites. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. 1976.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - ^ Donner, Herbert (1995). The Mosaic Map of Madaba: An Introductory Guide. Palestina Antiqua, 7. Leuven: Peeters Publishers. pp. 39–40. ISBN 978-90-390-0011-3.

- ^ "Madaba Mosaic Map: Peraea and Dead Sea". Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ^ Netzer, Ehud (2008). Architecture of Herod, the Great Builder. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic. pp. 234–235. ISBN 978-0-8010-3612-5.

- ^ Donner, H. (1963). "Kallirrhoë. Das sanatorium Herods des großen". ZDPV (79): 59–89.

- ^ Magness, Jodi (2003). The Archaeology of Qumran and the Dead Sea Scrolls. Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 77–78. ISBN 9780802826879.

- ^ Keay, John (2001). India: A History. Grove Press. pp. 13–14. ISBN 0-8021-3797-0.

- ^ See urban context for ancient greek baths Sandra K. Lucore and Monika Trümper, ed. (2013). Greek Baths and Bathing Culture: New Discoveries and Approaches. Babesch Supplements, 23. Leuven: Peeters Publishers. pp. 33–72. ISBN 978-90-429-2897-8.

- ^ Boëthius, Axel; Ward-Perkins, J. B. (1970). Etruscan and Roman architecture. Harmondsworth: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-056032-7.

- ^ Williams, Elizabeth (October 2012). "Baths and Bathing Culture in the Middle East: The Hammam". New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ^ See Sento About "Sento" Japanese communal bath house Tokyo Sento Association

External links

- "Madaba Mosaic Map". Retrieved 2 April 2016.