Capture of Columbia

| Capture of Columbia | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

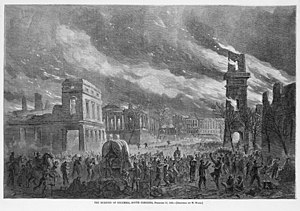

The Burning. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| William T. Sherman | Wade Hampton | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 98,355 | About 500 | ||||||

The capture of Columbia occurred February 17–18, 1865, during the Carolinas Campaign of the American Civil War. The state capital of Columbia, South Carolina, was captured by Union forces under Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman and much of the city was burned.

Background

Following the fall of Savannah, Georgia, at the end of his "March to the Sea", Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman turned his combined armies northward to unite with Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant in Virginia and to cut General Robert E. Lee's supply lines to the Deep South.[1] He planned to march through South Carolina to Columbia, then capture and destroy the Confederate arsenal at Fayetteville, North Carolina, before uniting with the XXIII Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. John Schofield, at Goldsboro, North Carolina. To confuse the Confederates, he sent his left wing westward towards Augusta and his right wing eastward towards Charleston.[2]

Confederate forces in South Carolina were part of the Department of the West, under the command of General P.G.T. Beauregard. He attempted to defend both Augusta and Charleston and divided his available forces between the two cities to defend them as long as possible. He hoped that doing so would give the Confederacy an advantage during negotiations at the Hampton Roads peace conference; he also thought that he could reconcentrate his forces if Sherman changed course for Columbia.[3]

The capture

Sherman was able to concentrate his army faster than Beauregard had anticipated and arrived at Columbia on the afternoon of February 16. The only Confederates defending the city were small detachments from Maj. Gen. Joseph Wheeler's cavalry corps, Maj. Gen. Matthew Butler's cavalry division, and Lt. Gen. Stephen D. Lee's corps from the Army of Tennessee. Heavily outnumbered, Lt. Gen. Wade Hampton ordered an evacuation of the city without a fight, although they destroyed all bridges over the Congaree and Saluda Rivers in an attempt to delay the Union forces. Sherman occupied Columbia the following day.[4] Much of Columbia burned to the ground in a fire that has engendered controversy ever since: some say it started when the Confederates set fire to cotton bales in the city, others say that drunken Union soldiers were fanning the flames of vengeance, while a few witnesses claimed that some of the fires were by accident.[5] James W. Loewen researched the topic for his book, Lies Across America, and found that most likely, the cotton bale fires spread and caused most of the destruction. He did find that there were some fires started by Union soldiers, but the effects of these were minimal. Most likely, the Confederates' scorched earth policy was to blame for the burning of Columbia (in which not much of it burned).[6] After the burning, Sherman was quoted as saying that he never gave the order to burn Columbia to the ground but he was not sorry that it happened.[citation needed]

Notes

References

- Barrett, John G. Sherman's March through the Carolinas. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1956. ISBN 0-8078-4566-3.

- Bradley, Mark L. Last Stand in the Carolinas: The Battle of Bentonville. Campbell, CA: Savas Publishing Company, 1996. ISBN 1-882810-02-3.

- Hughes, Nathaniel Cheairs, Jr. Bentonville: The Final Battle of Sherman and Johnston. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996. ISBN 0-8078-2281-7.

- Loewen, James W. "Lies Across America". New York: Simon & Schuster 1999. ISBN 0-7432-9629-X.