Clinton Edgar Woods

Clinton Edgar Woods (February 7, 1863 - 1930) was an electrical and mechanical engineer, inventor, manufacturer of automobiles in Chicago and New York City[1] author of one of the first books on electric vehicles, and early management author.[2]

Biography

Woods was born in Belchertown, Massachusetts, where his father was a coachbuilder.[3] At early age he was left orphan and obligated to earn a living and acquire an education.[4] Woods moved to Pittsfield, Massachusetts, in 1871.[5] He received his technical education in mechanical and electrical engineering at the Boston School of Technology[6] (nowadays Massachusetts Institute of Technology), which in his time was the first American university to offer a curriculum in electrical engineering.

In 1886 Woods drifted into steam and electric work at local central stations at Pittsfield, Massachusetts, at Peekskill and at Newburg, N.Y.. Subsequently he worked in general construction and engineering. In 1889 he joined the National Electric Manufacturing Company in Eau Claire, Wisconsin. He started as inspecting engineer, and became electrician-in-chief in 1892. In 1892 he joint the Standard Electric company in Chicago,[4] later in the 1890s he started two automobile manufacturer companies: the American Electric Vehicle Co. in 1895, and the Woods Motor Vehicle Co. in 1896.[5] After an unsuccessful start, the Woods Motor Vehicle Co. made a restart in 1899.[7] Woods became general manager of the Fisher Equipment Company in Chicago, the company that build the bodies for the American Electric Vehicle cars.[8]

In July 1899 Woods initiated an automobile club of wealthy drivers to promote the automobile interest, after the South Park board in Chicago had banned the automobile from streets and boulevards.[9] Woods left the Fisher Equipment Company in 1901 and became a car dealer[3][10] for which he founded the Woods-Wering Co.[5] Woods sold electric cars and trucks, among others to the U.S. Postal Service and the U.S. Army Signal Corps,[11] but this dealership did not last long. In 1905 Woods held an important position with the International Harvester Company, and subsequently at the Pope Manufacturing Company and the Pennsylvania Reaper Company.[3]

In 1900 Woods had also started writing, and published one of the first books on electric vehicles. Afterwards he wrote more books on accounting, business, and factory management. Since 1907 these were published under his own C. E. Woods & company based in Brooklyn, N.Y, later Woods publishing company. In the 1910s he moved to Bridgeport, Connecticut, where he continued to work under the flag of Woods Industrial Engineering Company. Among other things he developed and offered mail order courses of study in Industrial Engineering,[12] and was advisory engineer at Remington Arms.[13] In the 1920s Woods also became one of the directors of the National Bank of Commerce in Philadelphia.[14] Over the years Woods kept making inventions, and obtained over a few dozen patents.

Woods was married to Ida Norma Humphrey in 1881, and they had one daughter Florence Estella, born in 1882 and known to be the "first lady to own and operate an automobile in New York City."[1] Woods died in Yeadon, Pennsylvania in 1930, leaving his patents to be assigned to Julia E. Woods.[15]

Work

In the 1890s Woods came into prominence in the West of the United States as electrical worker.[4] He is further noted for starting two automobile companies, the second building cars under the name "Clinton E. Woods." Woods is further remembered for published one of the first books on electrical cars, and several works on management and accounting.

Electrical engineering

Woods came into prominence in the emerging field of electrical engineering late 1880s and early 1890s. An 1894 article in Western Electrician mentioned, that Woods work had "won for him reputation and prominence in the electrical field. He has designed for [the Standard Electric company in Chicago] a complete line of arc, alternating and constant potential dynamos, motors, etc., such accessories as transformers and instruments for perfecting the system, during the last twelve months." [4]

Furthermore, the article mentioned, that Woods is "not only an electrician but a manufacturer, having advanced many improved methods of manufacturing dynamo-electric machinery, which have greatly enhanced the value of his work from an artistic and mechanical standpoint. From the knowledge and ability Mr. Woods has displayed and opportunity for results which are in his possession, much is looked for from his future work."[4]

Automobile manufacturer

In Chicago in 1895 Woods founded the automobile manufacturer company American Electric Vehicle Co with the support of Samuel Insull[3] with a capital stock of $250,000. This company merged in 1898 with Indiana Bicycle Co. to become Waverly,[8] and later as Pope-Waverley would produce cars until the year 1914.[8][16]

In Chicago in 1896 Woods founded the Woods Motor Vehicle Company to manufacture electric automobiles. At first the company turned out to be unprofitable, and had to be re-capitalized. In September 1899 the Woods Motor Vehicle Company made a restart based in New Jersey with a capital stock injection of $10,000,000 by Samuel Insull, August Belmont, Jr., and some other Standard Oil investors. Woods lost his equity position,[8] and was at first installed in the position as General Manager[17] of the company, that build the bodies for the American Electric Vehicle cars, and later as consulting engineer. The car company eventually produced 8 different type of models.[18]

The Electric Automobile: Its Construction, Care. and Operation

As pro-car advocate[19] in 1900 Woods published the book "The Electric Automobile: Its Construction, Care. and Operation," which is a particularly interesting for the engineering of early electrics.[20] About the reach capacities of electric automobiles, Woods explained:

- Manufacturers of electric automobiles are often asked the question: "Will not a battery sometime be made to run a vehicle one hundred or more miles on one charge?" While this may be possible, the writer hardly thinks it will ever be probable, and his experience with the public is that it is wholly unnecessary, speaking generally and from a practical point of view. Improvements now being made in batteries, in the attempt to make them stand more rapid charges and discharges are much more important than one which will give them a larger mile-age capacity...[23]

About speeding with electric automobile, Woods further explained:

- Manufacturers of automobiles in the United States are confining themselves, without exception almost, to a maximum speed within the limits cited, and as very few accidents have occurred in the use of electric automobiles from fast driving, it is safe to say that when city councils do take up the question, all of these things will be considered, and a reasonably fast speed allowed automobile users. Surely twelve to sixteen miles an hour is fast enough when we consider that in city work it is practically double the speed and one-half the time made by the horse.

On the first introduction of motor vehicles, a great deal of stress was laid on speed, articles appearing in many papers advocating extremely high speeds, and in some of the tests and races given in this country, nearly fifty per cent of the value of an automobile as a prize v/inner was placed in its speed. The absurdity of this, however, is already proven. Almost any speed desired can be obtained from an electric automobile. It is simply a question of power application and gearing, and those who wish to ride at breakneck speed should only be allowed to do so in places provided for the use of high-speed and racing machines, as roadways or racing tracks set aside for their exclusive use, which will no doubt in time come in the same way that they have been provided for horses.[24]

The book further focussed on the elementary conditions of the electric automobile, its construction and rules concerning care and skillful operation. Woods stipulated that "the automobile is not a single item produced like the bicycle and sewing-machine," but comes with "a wide range of application in its utility and design,... a wide range of prices in its cost of production and marketing,... [and] a multitude of different elements to cater to by the various demands for its usage."[25]

Organizing a factory: an analysis of the elements in factory organization

In 1905 Woods published his first book on management and organization, entitled "Organizing a factory: an analysis of the elements in factory organization," which second edition was published in 1907. In this work Woods aimed to present an analysis of the elements in factory organization, the fundamental principles of factory management, and the methods to be used in every department of factory operation. In the Preface (1905) he further explained:

- American business men hold that the only way to learn to do things is to do them. This opinion has had much truth and fact to justify it, but it has been undergoing a marked transformation in the past decade. For men are coming to realize that, although no one can learn to do a thing by merely being told how it is done, such precious knowledge greatly facilitates his learning how to do it when once he gets into practical work. It affords him a strong foundation, barren and useless in itself, but a firm basis upon which to build the structure of business experience.[26]

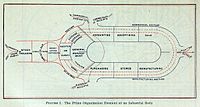

Woods visualized the fundamental principles of factory management in a series of four diagrams, showing organization elements (I); authorities (II); segregation of authority (III); and expenditure divisions of a factory (IV). This visualisation is an early example of resp. a flow diagram; a business process modeling or even a business reference model; an organization chart; and a visualization of management accounting:

About the segregation of an industrial body into authorities and departments Woods further explains:

- Figure III shows the segregation of an industrial body into authorities and departments. This chart shows the absolute division between the commercial and manufacturing ends of the business emphasized in the accompanying discussion and the authority lines connect the various departments in these two divisions with the governing authorities. In each case the number and formal name of each department is in the apex of its triangle, the various detailed duties that come under it are grouped beyond; the productive departments in the manufacturing section are left empty, because their work will vary with the kind of factory under consideration—each factory carries the same non-productive departments.[27]

The third picture was five years later republished in Parsons' Business Administration (1909). He commented, that the diagram "represents in detail the various branches of a large manufacturing concern. First the origin, elective power and executive heads of the company; then the producing, accounting and sales departments... with all their miscellaneous duties."[28]

Due to these works Woods is recognised as being among the foremost early 20th century writers on accountancy and management, with others such as Henry Metcalfe, Frederick Winslow Taylor, C.E. Knoeppel, Harrington Emerson, Horace Lucian Arnold, Charles U. Carpenter, Alexander Hamilton Church and Henry Gantt.[2][29]

Publications

Books, a selection:

- 1900. The Electric Automobile: Its Construction, Care. and Operation. H. S. Stone & co. in Chicago, New York. Re-published 1988, 2008

- 1905. Organizing a factory: an analysis of the elements in factory organization... The System Company, Chicago (2e ed. 1907; new ed. 1917)

- 1908. Woods' report on industrial organization, systematization and accounting. C. E. Woods & company in Brooklyn, N.Y .

- 1908. Practical costs accounting for accountant students, New York, Universal business institute, inc.

- 1909. Industrial organization, systematization and accounting. New York : Woods publishing company. (2e ed. 1915)

- 1917. Unified accounting methods for industrials. The Ronald press company in New York

- 1922. Analytical balance sheets for industrials.. Philadelphia

Patents

- 1895, Patent US546,691 - Continuous current rectilinear motor

- 1898, Patent US620628 - Apparatus for controlling operation of motors

- 1989, Patent US648014 - Vehicle

- 1899, Patent US6I9,527 - Motor vehicle

- 1913, Patent US1163120 - Graphophone

- 1913, Patent US1184907 - Talking-machine

- 1913, Patent US1192026 - Speed-governor

- 1913, Patent US1203088 - Start and stop device for talking-machines

- 1914, Patent US1214106 - Talking-machine

- 1918, Patent US1253328 - Combined governor and speed-indicator for talking-machines

- 1925, Patent US1564921 - Mounting for phonograph motors

- 1929, Patent USD81423 - Casing for a floor polishing

References

- ^ a b Sophia Smith (1903) Mack genealogy. The descendants of John Mack of Lyme, Conn., with appendix containing genealogy of allied family. p. 332

- ^ a b Yehouda A. Shenhav (2002). Manufacturing Rationality: The Engineering Foundations of the Managerial Revolution. Oxford University Press. p. 221

- ^ a b c d Gijs Mom (2004) The Electric Automobile: Its Construction, Care, and Operation p. 29

- ^ a b c d e Clinton E. Woods, in Western Electrician (1894). Vol 14-15. p. 244

- ^ a b c Halliday Witherspoon (1902) Men of Illinois p. 52

- ^ Nigel Burton (2013) History of Electric Cars. 2013. p. 101.

- ^ "Woods Motor Vehicle Company". The Crittenden Automotive Library. Retrieved November 6, 2014.

- ^ a b c d Car Companies on earlyelectric.com. Accessed May 7, 2013

- ^ Dominic A. Pacyga. Chicago: A Biography. 2009. p. 232.

- ^ Albert Mroz (2010). American Cars, Trucks and Motorcycles of World War I. 2010. p. 402.

- ^ Plus ça Charge: 1916 Woods Dual Power, An Early Gas/Electric Hybrid of Surprising Sophistication on toplevelnetworks.com by Ronnie Schreiber, February 22, 2014.

- ^ Furniture Manufacturer and Artisan (1918). Vol 77, Nr. 16. p. 98

- ^ Journal of Accountancy. Vol. 25, (1918), p. xxxi.

- ^ Business (1925) Vol. 6, Nr. 6 p. 5.

- ^ Patent USD81423 - Casing for a floor polishing: The descibtion from June 17, 1930 on the patent filed by Woods June 12, 1929 writes: "Be it known that CLinton E. Woods, deceased..."

- ^ The Waverley Company on earlyelectric.com. Accessed May 7, 2013

- ^ "Woods Motor Vehicle Company Incorporated with a Capital of $10,000,000]" The New York Times, September 28, 1899. (online)

- ^ Curtis Darrel Anderson,Judy Anderson. Electric and Hybrid Cars: A History. 2005. p. 21

- ^ Imes Chiu. The Evolution from Horse to Automobile: A Comparative International Study. 2008. p. 106

- ^ David P. Billington, David P. Billington Jr. Power, Speed, and Form: Engineers and the Making of the Twentieth Century. Princeton University Press, 2013. p. 234.

- ^ Woods, 1900, p. 20

- ^ Woods, 1900, p. 156

- ^ Woods, 1900, p. 13

- ^ Woods, 1900, p. 47-8

- ^ Woods, 1900, p. 40

- ^ Woods (1905, p. 3)

- ^ Woods (1905, p. 20)

- ^ Carl Copeland Parsons. Business Administration, (1909), p. 27.

- ^ Wilmer L. Green. History and Survey of Accountancy. 2014. p. 134