Codex Vigilanus

The Codex Vigilanus or Codex Albeldensis (Spanish: Códice Vigilano or Albeldense) is an illuminated compilation of various historical documents accounting for a period extending from antiquity to the 10th century in Hispania. Among the many texts brought together by the compilers are the canons of the Councils of Toledo, the Liber Iudiciorum, the decrees of some early popes and other patristic writings, historical narratives (such as the Crónica Albeldense[1] and a life of Mohammed), various other pieces of civil and canon law, and a calendar.

The compilers were three monks of the Riojan monastery of San Martín de Albelda: Vigila, after whom it was named and who was the illustrator; Serracino, his friend; and García, his disciple. The first compilation was finished in 881, but was updated up to 976. The original manuscript is preserved in the library of El Escorial (as Escorialensis d I 2). At the time of its compilation, Albelda was the cultural and intellectual centre of the Kingdom of Pamplona. The manuscripts celebrate with illustrations not only the ancient Gothic kings who had reformed the law — Chindasuinth, Reccesuinth, and Ergica — but also its contemporary dedicatees, the rulers of Navarre: Sancho II of Pamplona and his queen, Urraca, and his brother Ramiro Garcés, King of Viguera.

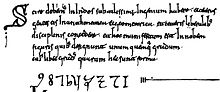

The Codex contains, among other pieces of useful information, the first mention and representation of Arabic numerals (save zero) in the West. They were introduced by the Arabs into Spain around 900.

The illuminations are stylistically unique, combining Visigothic, Mozarabic, and Carolingian elements. The interlace patterns and the drapery show Carolingian, as well Italo-Byzantine, influence.[2] The use of animals as decoration and for supporting columns also parallels contemporary Frankish usage.[3] More Carolingian and less Byzantine influence is evident in the Codex Aemilianensis, a copy of the Vigilanus made at San Millán de la Cogolla in 992 by a different illustrator.[4]

Notes

Sources

- Latin text

- Guilmain, Jacques. "Interlace Decoration and the Influence of the North on Mozarabic Illumination (in Notes)." The Art Bulletin, Vol. 42, No. 3. (September, 1960), pp 211–218.

- Guilmain, Jacques. "Zoomorphic Decoration and the Problem of the Sources of Mozarabic Illumination." Speculum, Vol. 35, No. 1. (January, 1960), pp 17–38.

- Guilmain, Jacques. "The Forgotten Early Medieval Artist." Art Journal, Vol. 25, No. 1. (Autumn, 1965), pp 33–42.

- Bishko, Charles Julian. "Salvus of Albelda and Frontier Monasticism in Tenth-Century Navarre." Speculum, Vol. 23, No. 4. (October, 1948), pp 559–590.